Presentation 8 Detecting the Parameters of Interaction and

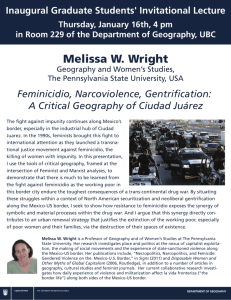

advertisement

University of Thessaly Department of Planning and Regional Development Graduate Program in European Regional Development Studies Fall Semester, 2011-12 Course: The Geography of European Integration: Economy, Society and Institutions Lecturers: Petrakos G., Camhis M., Kotios A., Topaloglou L., Tsipouri L., Bogiazides N. UNIVERSITY OF THESSALY Department of Planning and Regional Development Polytechnic School Post Graduate Program: European Regional Development Studies Course: The Geography of European Integration: Economy, Society and Institutions Detecting the parameters of interaction and development along the EU Border Space Dr. Lefteris Topaloglou 12th December 2011, Volos Introduction • The abolition of the artificial impediments of cross border interaction within the EU, has not only reduced barriers of trade but also brought to the fore a new mix of threats and opportunities that has put the EU border regions in a state of flux • Since the role of boundaries as obstacles to interaction institutionally, at least fades out, the potential of border regions has to be analyzed not only in relation to their national centers but also in relation to their neighbors and the enlarged EU space as well. 3 Objective …detect the economic, spatial and social determinants of growth in the EU border regions, in order to provide a better insight into theory and policy making Methodology Empirical model for growth performance in the EU border regions, taking into consideration the pertinent theoretical discussion and compiling a cross-section econometric model Estimation Technique …accounts for growth performance in the 349 EU NUTS III border regions during the period 2000-2006, incorporating quantitative and qualitative parameters of growth. 4 Economic geography literature (1) The intensity of interaction drops where a border crosses a place (McCallum, 1995; Helliwell, 1997; Bröcker, 1998) In a closed economy, border regions are zones of low opportunities due to their regional character, and distorted areas in terms of market size (Dimitrov et.al., 2002; Hoover, 1963; Hansen, 1997; Lösch, 1944; Cristaller, 1933 ) • Market size of the neighbouring countries affects significantly the location decision of firms and consequently the economic geography of borders (Damijan and Kostevc, 2002; Amiti, 1998; Hanson, 1998; Resmini, 2003; Fazekas, 2003) Placing a border and removing a border is not a symmetric action due to the significant role of “initial conditions” (Petrakos and Topaloglou, 2008; 5 Economic geography literature (2) Market potential and proximity to markets of each border region in the broader European space matters (Harris, 1954; Melchior, 2008). Low trade costs and increasing return of scale drive firms closer to large markets (Weber, 1909). In open economies, some places offer cheaper access to foreign markets, due to locational advantage (Villar, 1999). Foreign demand drives domestic firms to relocate closer to the borders. However, foreign supply drives domestic firms to relocate to the interior, away from the foreign competitors (Brülhart et al. (2004). Trade opening is associated with spatial divergence or convergence in border space. Previously less developed regions with better access6 Interdisciplinary approach Traditional studies on border areas are often enclaved in a “soledisciplinary approach” or in a “unitary case syndrome” without providing a substantial added value on border theory (Paasi, 2005, Agnew, 2005). Recently, “access” to foreign markets is examined in a broader framework, taking into consideration transport and telecommunication networks, institutional factors, and a series of political and cultural parameters (Topaloglou et. al. 2005). Perceptions and images of people occupy a fundamental position to interpret cross border economic interaction and growth (Van Houtum, 1999, Barjak, 1999). Economic potential of border regions is determined among others, by culture, language, nationality and other socioeconomic and geopolitical characteristics of border regions (Reitel, et al. , 2002; Arbaret-Schulz et al., 2004). The New Economic Geography (NEG) paradigm Firms, tend to move towards the large markets due to reduction in trade cost and nominal wages (Krugman, 1991, Fujita, 1993). Workers are attracted by higher real wages and the wider product variety found in agglomerations, making the location of firms in the actual place more profitable (Krugman, 1991, Fujita, 1993). Centripetal forces (market size effects, thick labor markets, informational spillovers) increase the variety of goods, decrease prices and raise profits if trade costs fall below a critical level (Krugman, 1998). However, centrifugal forces (immobile factors, land rents, pure external diseconomies) come to the fore mainly due to congestions costs and intensive competition (Tabuchi and Thisse (2002). Theoretical Model (a) The economic geography of border regions BEFORE the abolition of border obstacles Border Line WEST EAST ε΄ Producer D Ζ Χ Κ Producer C Ο Producer Β Y Producer Α Theoretical Model (b) The economic geography of border regions AFTER the abolition of border obstacles (a) Border Line WEST EAST ε΄ Producer D Ζ Χ Κ Producer C Ο Producer Β Y Producer Α Theoretical Model (c) The economic geography of border regions AFTER the abolition of border obstacles (b) Border Line WEST EAST ε΄ Producer D Ζ Χ Κ Producer C Ο Producer Β Y Producer Α Empirical model for growth performance (1) • Cross-section Econometric model for growth performance in EU border regions • 349 EU NUTS III border regions. • Quantitative (“hard”) and qualitative (“soft”) data (sources: ESPON database 2006 & EXLINEA FP5 Research Project, National Statistics). • WLS method (weighting variable: population). Yr ,T a 0 (a X , r , t ) r , t 1 Y: dependent variable, X: set of λ independent variables, aλ: set of estimators of the λ independent variables, a0: constant term, ε: disturbance term, r: region, t: initial year (2000), T: period (2000-2006). 12 Empirical model for growth performance (2) • Dependent variable (2000-2006): per capita GDP real growth performance in the EU (PCGDPGR0006) • Independent variables (2000): Per capita GDP (PCGDP00) Number of employees in the primary sector (PRIMEMP00) Spatial structure (SPATSTRU00); ESPON data, dummy variable (1: city core region, very densely populated region, 0: rural region, less densely populated region) Accessibility (ACCESS00); categorical variable, ESPON data (0-4, combined effect of geographical position and location advantage provided by the transport system) Coast (COAST00); dummy variable (1: coastal region, 0: landlocked region) 13 Empirical model for growth performance (3) • Independent variables (2000) (cont.): Environmental hazards (ENVHAZ00), composite ESPON variable Minorities (MINOR00); dummy variable (1: strong presence, 0: weak / no presence) Religion (RELIG00); dummy variable (1: common / similar religion with the neighboring region, 0: different religion with the neighboring region) 14 Determinants of growth performance (1) Independents PCGDP00 PCGDP00^2 PRIMEMP00 SPASTRU00 ACCESS00 COAST00 ENVHAZ00 MINOR00 RELIG00 2 R adj F N Dependant variable: PCGDPGR0006 b-estimator t-statistic -5 -3.78 10 -10.21*** -10 6.35 10 6.93*** -0.001 -1.85* 0.049 1.73* 0.074 3.69*** 0.067 2.05** -0.001 -3.14*** 0.199 2.40** 0.185 2.31** 0.733 101.37 329 15 Determinants of growth performance (2) • Determinants of growth performance: PCGDP00: non-linear pattern of growth; after a threshold (29,764 euros / inh.) the most dynamic border regions (9 regions) grow faster, and divergence forces dominate; co-existence of convergence and divergence forces in different proportions PRIMEMP00: negative impact; primary sector is a low-productivity sector SPATSTRU00: positive impact; core and more densely populated border regions generate higher rates of growth performance 16 Determinants of growth performance (3) • Determinants of growth performance (cont.): ACCESS00: positive impact; transport infrastructure endowments generate higher growth performance, contributing to the coherence of border areas COAST00: positive impact; advantage of the coastal border regions over the non coastal ENVHAZ00: negative impact; environmental hazards put economic prosperity in danger MINOR00: positive impact; strong presence of minorities contributes to growth RELIG00: positive impact; common/similar religion contributes to growth: confirmation of earlier arguments e.g. Weber, 1930 17 Conclusions Methodology: • The study broadens the discussion on the growth determinants of border regions, taking into consideration not only quantitative (“hard”) but also qualitative (“soft”) parameters. Theory: • The study of border regions needs an interdisciplinary approach. • Co-existence of convergence and divergence forces; Non-linear growth pattern; Coexistence of neoclassical and “cumulative” approaches? Policy Making: • What should be the mix of cross-border policies in order to contribute to the decline of economic heterogeneity, to the increase of spatial coherence, and to growth? • The principle “one size fits all” does no longer seem appropriate. 18 Some Policy Recommendations for discussion Establishing Environmental Trust Set up of “Clever” Actions Joint Cross Border Planning 19 Thank you for your attention! 20