The Sophoclean Hero During his long career Sophocles wrote

advertisement

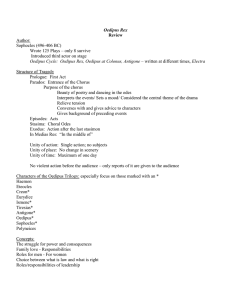

THE SOPHOCLEAN HERO During his long career Sophocles wrote something of the order of 123 plays; of these, only seven remain in full. In six of those seven – Ajax, Antigone, Oedipus the King, Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus – there is a single character who dominates the action, in each case the title character of the play. (The exception is his play The Women of Trachis, which has two main characters who never actually meet; it’s interesting that this is the only one of the seven which is named after its chorus.) It’s not unusual for Greek tragedies to have a main character. But there’s something about the figures who dominate these six plays that has led to a certain fascination with the idea of the ‘Sophoclean hero’. The idea of the ‘Sophoclean hero’ achieves its most powerful expression in a classic book published almost exactly fifty years ago: Bernard Knox’s book The Heroic Temper. Studies in Sophoclean Tragedy, which first appeared in 1964. There’s a case for saying that this is the most important and influential study of Sophocles published in the twentieth century. It’s not very long – just over two hundred pages, including the indexes. It’s written in a really engaging style – the text originated as a prestigious series of lectures given in Berkeley, California in 1963, and since the book was published only the following year he clearly didn’t wait to revise it before publication, and so it often has the freshness of direct speech. The book has a particular point of view which Knox seeks to put across to his readers in the most persuasive way possible. When you compare this to most academic books – written in boring prose, sitting on the fence, and ten times as long as they need to be – you can begin to understand just why generations of students and scholars alike have turned to Knox to learn about Sophocles. 1 In the first two chapters of his book, Knox describes the characteristics shared by six of Sophocles’ protagonists. The style really is engaging. ‘The hero’s decision’, Knox writes, ‘his resolve to act, that rock against which the waves of threat and persuasion will break in vain, is always announced in emphatic, uncompromising terms’. He then illustrates his claim with many passages directly quoted in translation from the plays: in this case, lots of statements by the main characters in which they declare forthrightly what they are going to do. Knox’s dramatic prose style, interwoven with countless brief, pithy quotations, makes for a really persuasive text. As you’re reading it, it seems that Knox simply must be right; how else could he asssemble all these passages in favour of what he is saying? He goes through the characteristics that these figures share: firmness of will, refusal to listen to advice, isolation, preference for death over surrender, and so on. In each case, one passage follows another in quick succession, illustrating the characteristic in question and bludgeoning the reader into accepting Knox’s case. His concluding summary of the figure that he calls ‘the Sophoclean hero’ is pretty heroic itself in its grandeur, and deserves to be quoted in full: ‘Such is the strange and awesome character who, in six of the Sophoclean tragedies, commands the stage. Immovable once his decision is taken, deaf to appeals and persuasion, to reproof and threat, unterrified by physical violence, even by the ultimate violence of death itself, more stubborn as his isolation increases until he has no one to speak to but the unfeeling landscape, bitter at the disrespect and mockery the world levels at what it regards as failure, the hero prays for revenge and curses his enemies as he welcomes the death that is the predictable end of his intransigence. It is an extraordinary figure, this Sophoclean tragic hero’. 2 Sophocles himself might have been proud to write like that. But let’s look a little more closely at what Knox is trying to do. He’s not simply looking for similarities between these characters for their own sake. He has a particular agenda. According to Knox, ‘it is through the refusal to accept human limitations that humanity achieves its true greatness. It is a greatness achieved not with the help and encouragement of the gods, but through the hero’s loyalty to his nature in trial, suffering, and death; a triumph purely human then, but one which the gods, in time, recognize and in which they surely, in their own far-off mysterious way, rejoice’. In the copy of this book in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, someone has written next to the final sentence ‘Bah! You’re over-optimistic’. Another person has written ‘how do you know?’ Oxford is a bit like that – even the graffiti is pretty learned. I’m sorry that these comments are unsigned, because they lie at the heart of what I want to talk about today; generally I disapprove of writing in library-books, but on this occasion I’ll make an exception, and I’m just sorry that I can’t give these learned and sceptical readers the credit that they deserve. Knox is absolutely right that the six characters who star in those plays by Sophocles – Ajax, Antigone, Oedipus the King, Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus – share a lot of characteristics. What he doesn’t do is prove that these characteristics are admirable, that we should approve these people because they are stubborn, determined, impervious to advice, and so on. After all, it’s not obvious that all these characteristics are always admirable. A terrorist can be totally determined – to cause as much mayhem as possible, and can stubbornly refuse to change his mind – and we certainly don’t admire him for his determination and resolve. And Knox also doesn’t take enough account of the real differences between the characters, and changes in individual characters during the course of a particular play. Both of these 3 reasons make me very cautious about talking about ‘the Sophoclean hero’. In fact, in my own work on Sophocles, it’s a phrase I now avoid. The problem is partly linguistic. ‘Hero’ in English means a lot of different things. It can mean ‘the chief male character in a poem, story, play, etc.’ (I cite the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary), but it can also mean ‘a man admired and venerated for his of her achievements and noble qualities in any field’. The first sense is morally neutral: you can say that Macbeth is the hero of Shakespeare’s play, and it doesn’t mean that you’re in favour of killing old men in their beds and murdering the children of your political opponents. But the second sense is morally approving. When Knox uses the expression ‘the Sophoclean hero’, which sense does he mean? The first sense is obviously legitimate, although not very interesting: Sophocles wrote plays which contained chief characters. But if we are to use it with the second sense – that is, if we are to say that these protagonists excite admiration – we need to argue the case. The problem is, Knox never actually does that. He details all these characteristics that the characters share, but never tells us why we should approve of them, never says why their behaviour constitutes a ‘human triumph’ (his words) or why the gods should ‘rejoice’ in what they do. He seems to rely instead on verbal slippage between the two senses of ‘hero’, as if the mere fact that these characters are main characters (‘heroes’ in the first sense) also means that they are people that we approve (‘heroes’ in the second sense). Perhaps Knox thought that the characteristics that he described – resoluteness, unwillingness to be persuaded, determination to carry through their resolve even if death is the cost – are so obviously admirable that he doesn’t need to argue his case. In this he might have been influenced by the existentialist philosophy that was very much in vogue at the time that he was writing. 4 According to existentialist philosophy, keeping true to your own basic nature was the most important thing that you could do, even if you had to sever relationships with other people – doing anything else leaves you open to the charge of inauthenticity. But another scholar sees the problem in applying that idea to Sophocles’ plays, in particular the Ajax: ‘His final actions, terrible, irrevocable, make Ajax, from the modern perspective, an existential hero for his refusal to endure life on any terms other than those he himself finds acceptable. How a fifth-century audience in Athens would have responded to this resolute intransigence is less easily ascertained.’ You will search in vain in Knox or his followers for any attempt to address this problem. Let’s look at Ajax a bit in detail now. At the start of the play, we don’t see Ajax himself: instead, Odysseus is hunting around the stage. Athena then appears and asks what he is doing; Odysseus replies that there has been an attack on the animals kept in the Greek camp, and Ajax is a suspect. The exchange between Odysseus and Athena is on the handout: the goddess reveals to Odysseus not only that Ajax did indeed kill the animals, but his intention was to kill the entire Greek army while they slept. Only Athena’s intervention sent him mad and made him attack the animals instead. Ajax’s motive for his attack – and we must remember that he was sane when he set out – was the decision to award Achilles’ armour to Odysseus instead of to Ajax. However angry and disappointed Ajax was when he came second to Odysseus, an attempt to kill the entire army seems a hugely disproportionate response by ancient as well as by modern standards of morality. It’s hard to see how someone who attempts such a horrific crime could be hailed as a ‘hero’ in any culture – because any culture that gave such intense prestige to such destructive acts simply wouldn’t last very long. But, the answer, comes, Ajax is merely following the heroic 5 code. According to that code, the most important thing in the world was your personal honour; any attempt to diminish that honour would be met with massive retaliation. People often assert that Ajax is a particularly ‘Homeric’ hero, and that he’s doing exactly what Homeric heroes do when their honour is attacked. I’ve never quite understood this idea of the ‘heroic code’. What exactly is it? Is it like the Highway Code in the United Kingdom – a set of rules and regulations that all drivers, or heroes, have to know and follow at all times? Surely not. In my view, the only way we can tell what Homeric heroes do is to look at the Homeric poems and see how they act, and how others respond to how they act. And when we do that, we don’t find anything remotely comparable to Ajax setting off to murder all his fellow-comrades in their beds. The nearest comparison that people can cite comes from book 1 of the Iliad, when Achilles gets angry with Agamemnon because of an attack on his honour, and considers drawing his sword and killing him. But this is different. First, Achilles’ action would have been in broad daylight, in front of the army, and against an Agamemnon who was also armed and would have had the chance to defend himself. Second, Achilles’ action was conceived in the heat of the moment, not at leisure some hours after the event that had made him so angry. Third, Achilles doesn’t actually go through with it – thanks to his own good sense, and encouraged by the goddess Athena, he realises that that would be a disproportionate response. This is very different from Ajax’s response. There is nothing heroic about Ajax here that I can see, and we cannot invoke Homer to support him. Does this mean that we have no sympathy for Ajax at all in the play? I don’t think so. After the first scene we encounter the chorus, who are Ajax’s men, and are completely loyal to him. His concubine, Tecmessa, is also devoted to his interests, even if she cannot in the end persuade him not to kill himself. His half-brother Teucer 6 mounts a spirited defence of his interests in the last part of the play; this is where we first hear concrete examples of Ajax’s valour in battle, which are made more impressive than anything that we find in the Iliad in order to assist with Ajax’s post mortem rehabilitation. The Greek leaders who oppose Ajax’s burial, Menelaus and Agamemnon, are portrayed in such negative terms, and are given such bad arguments, that the audience cannot help but feel sympathetic to the man whose corpse they want to dishonour. And finally Odysseus himself, Ajax’s old enemy, intercedes to ensure his burial. This is the key point of the play – Ajax does get the honourable burial that he so desired, but not by force, but by the persuasive and honourable words of Odysseus. Sophocles reminds us that there is more to heroism than physical violence and murderous acts of self-assertion – heroism rather lies in standing up for others, in supporting what is right even though it does not directly affect your own honour. So if there is a hero of this play, in the sense of someone whose actions cause the audience to admire him, it is not Ajax, but Odysseus. By the end, the audience have learned to value what was great about Ajax, to see him in the round, the admirable as well as the extremely repulsive sides to his character. That’s why tragedy is worth reading and watching today, because it doesn’t offer simplistic evaluations of people – it forces us to reflect on the values of the characters portrayed, and thus on our own values. How much better that is than simply to apply a label to someone, and to give up thinking. Antigone is a very different case from Ajax. Whereas Ajax had set out at night to murder the army, she sets out at night to bury her brother, Polynices, who has been killed while leading an army to attack his home city of Thebes. And the person who killed him? Eteocles, his brother – who was also killed. Eteocles is to be buried with all honour as the defender of his homeland – so resolves the new king Creon. But Creon also decrees that Polynices’ body will not be buried, but will instead be kept 7 above grounds, as food for animals. The penalty for burying him is death. Yet Antigone is not deterred. Her resolution to bury her brother leads her to defy the king – a young woman defying an older man – even though she knows it will lead to her own death. She boldly admits her guilt, is led off to be buried alive, and kills herself in the underground chamber. What could be more heroic than that? The answer is indeed, ‘not much’. Antigone does indeed show extraordinary determination and willingness to do the best thing for someone else even at the cost of her life; her ability to stand up to wrongful authority is indeed something that audiences have admired through the centuries. So I’m not advocating some sort of revisionist view of her today. Nor am I saying, as a few scholars have who ought to know better, that because she was a woman, and a young one at that, the original male audience would not have sympathised with her. First of all, the audience for Greek drama in Athens included women – just about every serious scholar who has examined the evidence agrees on that – so we need to take their views into account too. Second, we have to be careful not to be patronising towards the men of fifth century Athens. Sure, they had attitudes about the place of women which we would find appalling today. On the other hand, that doesn’t mean that they would always take a man’s side in any dispute whatsoever. If an average Athenian man was walking down the road and saw a woman being assaulted by a man, I don’t think he would be pleased at this sight, any more than a man would today. And men also knew about the dangers of tyrannical rule, of unjust laws, and of the abuse of power. So we can’t say that Antigone is presented in a negative light simply because she’s a woman. Does that mean that our views of Antigone are wholly positive, with no room with doubt or dissent? No, it doesn’t, and thank goodness for that – such a monochrome character would be utterly uninteresting. Let’s look at how she interacts 8 with her sister, Ismene, in the text on the handout. At the start of the play she attempts to get her sister Ismene to help her; Ismene refuses, not because she doesn’t sympathise with her, but because she realises that such a course of action will not succeed and will lead to her own death. This is a quite reasonable point of view. It’s not cowardly; it’s not especially heroic, but we may wonder if the heroic response is always the right response. More to the point, Antigone’s response to her sister is fascinating. She concedes nothing to her at all; by failing to follow her, Ismene has betrayed her and her brother, and must be treated with contempt. Heroic Antigone may be, but is she sympathetic? Is there anything in her vision of the world which allows her to understand the hopes and fears of people different from herself? Later in the play, Ismene is brought on after Antigone is captured, and claims that she too was involved and needs to be punished. This is an extraordinary thing to do – one might, indeed, call it heroic. She feels so much for her sister that she can’t bear to think that she is going to be punished alone. Yet does Antigone welcome her? Far from it. She rejects her attempts to share in the punishment. When Ismene asks her ‘But if you’re gone, what is there in life for me to love?’, she replies ‘Ask Creon. He’s the one you care about’. Remember that this is Antigone’s last conversation with her own sister – Antigone, the woman who loved her brother so much that she was prepared to die to secure his burial. This is appalling emotional brutality. Antigone absolutely deserves respect and admiration for standing up for the laws of the gods that relate to burial. But her shocking treatment of her sister, who wants to support her in whatver way she can, means that our admiration is unqualified. She shows much more affection for her dead sibling than for her living one, and that may tell us quite a lot about the kind of person that she is. So heroic, yes: but that’s far from the full 9 story. The single-mindedness that she shows is far from a simple or wholly admirable quality. Oedipus in Sophocles’ Oedipus the King is perhaps the character who most obviously deserves the title ‘hero’. At the start of the play he is entreated by his citizens, who are suffering from a plague in the city, to find out some way of dealing with the trouble. As the priest says, Oedipus has saved the city in the past, when the Sphinx was terrorising it; now he is urged to do the same again. Truly this is a man regarded as a hero by his people. The priest even has to make clear that he regards Oedipus as the best of men, not as a god – only with truly great men do you have to stress that kind of qualification. Oedipus himself, it becomes clear, has already set things in motion to find out what is wrong – he’s sent his brother-in-law Creon to find out from the oracle at Delphi what the city needs to do. When Creon returns, and says that the Thebans need to punish the killer of Laius in order to be free from the plague, Oedipus declares that he will go to every length to track him down. His problem is that he does exactly that. Because you all know what eventually happens to Oedipus. It turns out that he is the problem that he is looking for – Apollo has sent the plague because Oedipus has remained unpunished for killing the former king, Laius, who (it becomes clear during the course of the play) was also Oedipus’ father; this horrible news is accompanied by the further atrocious fact that Oedipus has been sleeping with his mother, Laius’ former wife Jocasta. He’s done all of these things unwittingly – he didn’t intend to kill his father and marry his mother. But such ignorance barely counts for anything in face of the breaking of so many taboos. Can we see anything heroic in the career of Oedipus? I think we can. First, his concern for his people lead him to do everything to recover the truth, even when it becomes clear that this is leading to a conclusion that he would rather not reach. 10 When the Old Man who exposed Oedipus as a baby is about to provide the key piece of evidence which will show that this baby grew up into the man before him, who thus will have killed his father and married his mother, he tries to avoid to saying anything, but Oedipus tells him ‘If you won’t tell us of your own free will, once we start to hurt you, you will talk’ and actually goes so far as to order an attendant ‘One of you there, tie up this fellow’s hands’, as a preparation for torture. ‘Alas, what I’m about to say now . . . it’s horrible.’ ‘It’s horrible for me to hear’, says Oedipus, ‘But nonetheless I have to hear this.’ And then comes the terrible news. But even earlier in the play, when Oedipus thinks that he may been Laius’ killer – he does not yet suspect that Laius was his father – Oedipus is determined to find out the truth. He does not attempt a cover-up, as he might have done, being a powerful ruler with an excellent reputation. Such commitment to his people, and to the truth, can be truly described as heroic characteristics. A further type of heroism has been observed in the final scene of the play. There Oedipus re-enters the stage, having blinded himself as a punishment for his offences. His life has collapsed. He is no longer ruler of Thebes. More importantly, all his human relationships have been found to be based on falsehood. Yet despite his appalling predicament he remains a compelling figure – indeed, to an extent, a magnificent one. He begs to be cast out of the city as the polluting figure that he is. He declares that ‘no other mortal can bear my sufferings’, and the audience will certainly believe him. He persuades Creon to bring his daughters to him, and he is overcome by sorrow at the sufferings that they will undergo – his own pain does not prevent him from entering imaginatively into the lives of others. Right to the end he retains a desire for mastery - We may describe Oedipus as a hero, but that is far from summing up the meaning and significance of this terrifying play as a whole. 11 ‘Hero’ and ‘Sophoclean hero’ have become question-begging words. Used as default designators for individual characters, they implicitly evoke an unsupported set of assumptions. The audience may well admire individual characters at some points during the play, and their overall impression of them might in the end be positive; but it is foolish to use terms which imply that our investigation will inevitably conclude with such an outcome. It’s also foolish to use a term that suggests that these figures are basically all alike; for while they do have similarities, there are all kinds of crucial differences that we have to take account of in our responses. That’s why I avoid this term when writing about Sophocles. Keeping clear of prejudicial terminology, we should attempt to analyse to what extent individual characters excite the audience’s sympathy, pity, criticism, and admiration at different times during the play. The characters of Sophocles are far too interesting, far too multifaceted, to be all lumped together under a single one-size-fits-all label. Thank you. 12