Sample Poetry Research Paper - ibenglish3-mrso

advertisement

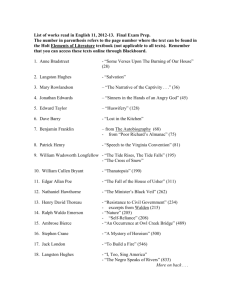

Smith 1 Sally Smith Mrs. Oehrlein English 3 IB 9 April 2013 Migration to Harlem The Harlem Renaissance was a time of cultural growth for African Americans in the early 20th century. This large scale movement was due to the Great Migration, which was the movement of six million African Americans from the South to the North, hoping to achieve a better life, between 1916 to 1970 (Great Migration). Many African American writers of the Harlem Renaissance wrote about this journey North, but one of the most famous writers was Langston Hughes. Although most white critics during the time did not take his writing seriously, and he was criticized for not going “much beyond one of his earliest themes, black is beautiful,” he eventually “achieved major recognition” for all of his works (Patterson, Blue). He wrote about the hope of the Great Migration, but also of the reality when the destination, especially Harlem, was reached. Through his poems, the true emotions of the Great Migration are expressed as despair in the South, hope for a better life in the North, and ultimately disenchantment with their new life there. “The South” is a poem that covers the contradictory feelings of the African Americans on their life in the South. Hughes uses a scheme of alternating positive and negative diction throughout the poem to emphasize the fact that the people of the South have forced them to leave the land that they love. Most of the negative phrasing deals with the people, “Idiot-brained/… child-minded South” while the positive refers to the beauty of the land such as, “sunny-faced” and “magnolia-scented South.” Such hyphenation and personification creates a stronger Smith 2 emotional message with vivid imagery throughout the poem. Hughes conveys the anguished pain of loving the South even when the love would cause harm, “Beautiful, like a woman./ Seductive as a dark-eyed whore,/ Passionate, cruel,/Honey-lipped, syphilitic--/That is the South.” On the other hand, the narrator describes the destination as “The cold-faced North” and “a kinder mistress.” The North was going to provide a new life for them but it was unknown and still with some harsh realities, but it would be better than the life in the South. Hughes sets the narrator apart, “I, who am black,” as opposed to a white southerner who would be loved by the South. Because of the rejection that the black narrator feels from his mother-land, there forms a relationship filled with both love and hate. On a scale, the hate outweighed the love and sent the African Americans on their long journey out of the South. Langston Hughes articulated this African American search for a new life in the poems “One Way Ticket” and “Bound No’th Blues.” “One Way Ticket” explains the reason why African Americans wanted to act upon changing their lives for the better. Repetition of the phrase, “I pick up my life/and take it…” clarifies the fact that the Southern blacks wanted to move out of the South and wanted nothing more of its way of live. Additionally the listing of all of the problems that were present for the African Americans, from “…Jim Crow Laws” to those who “lynch and run” to “People…who are scared of me/and me of them,” reiterates that there wasn’t just discrimination, but violence against blacks in the South. Additionally, through the listing of places to move to, a sense of freedom and choice is created, communicating that the narrator, speaking for all black people, wants to move in any direction except South. This gives a sense of optimism and high expectations that they will get away from “People who are cruel.” On the other hand “Bound No’th Blues” describes the hard journey from the laborious South to the hopeful opportunities in the North, but with somewhat less optimism. The multitude of Smith 3 repetition of “goin’ down the road” and “road” emphasizes the long and lonely journey to the North. Langston Hughes writes at the end of each stanza what the narrator hopes to find in the North. The first two are optimistic, “Got to find somebody/ To help me carry this load” and “I’d like to meet a good friend/ To come along and talk”; however the third faces the realization that the North might not be so welcoming to the migrants from the South. Yet the last stanza expresses there is no hope in the South, and the narrator feels that even if the North is not welcoming, he knows he can’t stay in the South. Through these two poems, Hughes describes the anticipation of the improved lives of the migrants once they arrive at their destination. In the poems “Restrictive Covenants” and “Good Morning”, Hughes describes the not so hospitable North towards the migrant African Americans. In “Restrictive Covenants” the people living in the neighborhood, even “every foreigner/ That can move, moves,” Hughes explains, as the northerners were not so keen on having African Americans as their neighbors. Perhaps the hope of getting completely away from the “people who are cruel and afraid” in “One Way Ticket” will not be achieved. Hughes uses italics to highlight the fact that the sun, the moon, and the wind treat everybody equally; these may be the only friends to count on since, “The moon doesn’t run./ Neither does the sun,” and “I reckon the wind/ Must care.” Also the italics make these lines stand out to the reader and give the sense that the narrator feels alone in the world. The word choice in the third stanza, “restricting me/Hemmed in” and “Can’t breathe free” connotes the feeling of being held back and not having accessibility to the necessity of life they were seeking – freedom. Also seeking freedom are the multitudes of immigrants described in “Good Morning.” However, the narrator in this poem is a knowledgeable native of Harlem who sees the “…dark/ wondering/ wide-eyed/ dreaming” immigrants arriving. Placing each of these words on separate lines emphasizes the optimism and the naivety of the immigrants. Hughes’ Smith 4 use of listing without comas signifies the large number of places that people are coming from, all with the same goals. That goal is the American Dream, as set forth by the Founding Fathers, who Hughes irreverently refers to as “daddy” in the first and last line of the poem. The narrator knows that the migrants will not find freedom easily, as “The gates open-/ Yet there’re bars at each gate.” This leads to the question posed at the end of the poem, “What happens/ to a dream deferred?” Hughes attempts to answer that question in his famous poem, “Harlem.” However in answering the question more questions evolve, indicating an unclear future. In these questions, the negative diction such as, “dry up”, “fester”, and “stink,” creates a feeling that nothing good is to come from the dreams that are being set aside. Additionally Hughes uses personification and simile as the dreams “run” away or “just sag” to create strong visuals to the possible future outcomes. Although all of the options that Hughes offers are negative, none are as extreme or devastating as the last line of the poem, “Or does it explode?”, which is italicized for emphasis. Tom Hansen suggests that the structural disunity of the poem “mirrors the continuing failure of American society to achieve harmonious integration of blacks and whites” which results in the frustration displayed in the poem (Hansen). Through the collection of poems discussed here, Hughes takes the readers on the journey with the African Americans in their quest to find a new life through the Great Migration. In all of the poems, Hughes displayed a “masterful grip on language and was in tune with his community” such that he skillfully conveyed the complicated emotions the African Americans had during the era. Initially there was injustice and hatred in the South, which caused a growth of hope for life anywhere else, particularly Harlem. But as travelers began to settle, they still “found themselves surrounded by prejudice, discrimination and segregation” (Lapucia). This Smith 5 resulted in a sad and potentially angry realization that the North was only going to give them slightly better conditions than the South, and that there was still a long road to travel for true freedom. Smith 6 Works Cited Blue, Medria. "96.01.02: Langston Hughes: Artist and Historian." Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Apr. 2013. "Great Migration." History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 09 Apr. 2013 Hansen, Tom. "On "Harlem"" Modern American Poetry. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Apr. 2013. "Harlem." By Langston Hughes : The Poetry Foundation. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Apr. 2013. Hughes, Langston. "Bound No’th Blues." PoemHunter.com. N.p., 27 Mar. 2010. Web. 7 Apr. 2013. Lapucia, Betty. "78.02.05: Migration North to the Promised Land." Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Apr. 2013. Patterson, Lindsay. "Langston Hughes -- The Most Abused Poet in America?" New York Times on the Web. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2013. "Poem Analyses - The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes." The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Apr. 2013. "Solomon's Great Migration 2012." : "One Way Ticket" By Langston Hughes. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Apr. 2013. "When I Move." When I Move. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Apr. 2013. "Who Do You Think Is the Speaker of This Poem?" Yahoo! Answers. Yahoo!, n.d. Web. 07 Apr. 2013.