1AC – KY Octas - openCaselist 2013-2014

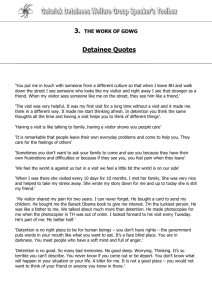

advertisement