Slide 1

advertisement

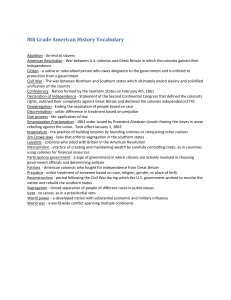

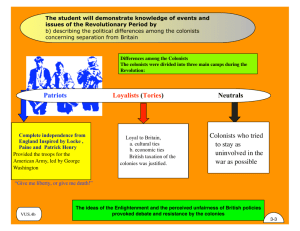

The Proclamation of 1763 brought a formal end to the era of Salutary Neglect. A series of new taxes and enforcement procedures further demonstrated that the British were going to change the rules on the colonies and further alienated colonists. Sugar Act, 1764; (a.k.a. Revenue Act): First in a series of laws enacted to force colonists to pay a portion of their defense. It actually reduced the tax on molasses, but now the tariff would be enforced. The Act also levied taxes on textiles, wine, coffee, indigo, and sugar. Currency Act, 1764: A chronic shortage of hard currency (specie) plagued the colonies. To overcome it, many colonies began printing paper money. British creditors feared payment in paper because of inflation. They wanted to be paid in gold or silver. The Currency Act prohibited colonies from paying debts with paper money. Paper money throughout the colonies lost value because no one would accept it. The combination of new taxes and the requirement to pay debts and taxes in specie sent shock waves through the colonial economy. Developments in 1765 made many colonists even more nervous about Parliament’s authority. Stamp Act, 1765: Enacted in February and to take effect in November, the law imposed a tax on all printed materials and legal documents: deeds, leases, licenses, wills, newspapers, pamphlets, etc. What made the tax even more troubling to colonists was that it was a direct tax: a tax added and paid directly rather than hidden in the cost like a tariff. Many colonial leaders were hit hard by the tax and sought a way to challenge Parliament’s authority. They latched on to political theories offered by British Whigs, in the tradition of John Locke. Among the most important opponents of the tax was James Otis. By no means a radical, nor wanting colonial independence, Otis had developed an argument against the taxes in 1764, in The Rights of the British Colonists Asserted and Proved. “The colonists will have an equitable right . . . to be represented in Parliament, or to have some new subordinate legislature among themselves. It would be best if they had both. . . . Besides the equity of an American representation in Parliament, a thousand advantages would result. . . . It would be the most effectual means of giving those of both countries a thorough knowledge of each others interests.” James Otis The key issue for the colonists was representation and governing with the consent of the people. Otis offered an argument in favor of “direct representation.” Delegates from each community would meet in an assembly, acting as agents for their constituents; they would debate, wheel-and-deal, and compromise their way to a policy satisfactory to a majority. Britain responded, arguing a concept called “virtual representation.” As Britain progressed into a more modern nation-state, regional differences diminished and were replaced by general or national interests. Thus, representation in Parliament gradually changed from local to national. Members of the House of Commons represented the interests not just of their particular constituents, but of all of the “commons.” The House of Lords, represented the interests of the gentry. Several issues made virtual representation inadequate in the colonies: (1) a more fluid social organization than Britain; (2) a more diverse population than Britain; and (3) the different interests involved in governing a frontier settlement from governing Britain. Of course sheer distant made direct representation inadequate, as well. “It is inseparably essential to the freedom of the people, and the undoubted rights of Englishmen, that no taxes should be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.” Patrick Henry In May 1765, Virginia led the attack on the Stamp Act. Patrick Henry asserted that colonials enjoyed the “Rights of Englishmen” and were exempt from any tax that did not derive from their own assembly. In June 1765, Massachusetts invited colonial assemblies to meet in New York to discuss a unified response to the Stamp Act. In the interim, resistance to the Stamp Act began. Bostonians hung an effigy of the stamp distributor from what would soon be called the “Liberty Tree” or “Liberty Pole.” Mobs, often calling themselves the “Sons of Liberty,” attacked the homes of tax collectors and stamp distributors, and even that of the Governor. The protests had the desired effect, as stamp distributors abandoned their posts. Soon just the threat of violence was enough for colonials to get their way. Nine delegations met in the Stamp Act Congress in New York, beginning in October. The Congress deliberated for three weeks and issued the “Declaration of Rights and Grievances. The key point is in Part 4 where the Congress discusses representation. 4. That the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council: and as the English colonists are not represented, and from their local and other circumstances, cannot properly be represented in the British parliament, they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved, in all cases of taxation and internal polity, subject only to the negative of their sovereign, in such manner as has been heretofore used and accustomed. But, from the necessity of the case, and a regard to the mutual interest of both countries, we cheerfully consent to the operation of such acts of the British parliament, as are bona fide restrained to the regulation of our external commerce . . . and the commercial benefits of its respective members excluding every idea of taxation, internal or external, for raising a revenue on the subjects in America without their consent. The Declaration warned of the actions colonies intended to take to make Parliament back down to “restore us to that state in which both countries found happiness and prosperity, we have for the present only resolved to pursue the following peaceable measures: 1. To enter into a non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation agreement or association. 2. To prepare an address to the people of Great Britain, and a memorial to the inhabitants of British America, and 3. To prepare a loyal address to his Majesty, agreeable to resolutions already entered into.” Many colonies enacted “Non-importation Agreements,” establishing boycotts of British goods. One result of the boycotts was that colonials could no longer buy British cloth or clothing. They began wearing homespun instead. This gave the revolutionary era a drab fashion, as homespun was a coarser fabric than British textiles and lacking in the variety of dye colors. The boycotts, Franklin’s lobbying, and support from British Whigs (notably Edmund Burke) caused Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. “Parliament has a right to bind the colonies in all cases whatsoever.” Declaratory Act, 1766 The repeal was a victory for the colonists, but Parliament moved to reassert its authority. It drew a distinction between indirect taxes and direct taxes. This left an opening to raise tariffs. Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, which asserted its right to enact taxes and any other laws on the colonies. Upon hearing of the Declaratory Act, John Adams wondered “whether they will lay a tax in consequence of [the] resolution.” The Revenue Act of 1767, better known as the Townshend Duties, placed tariffs (“external” taxes) on glass, lead, paper, paint, and tea. The law also set up a Board of Customs in Boston to collect the tax. Additionally, Townshend suspended all laws enacted by the New York Assembly until New Yorkers began obeying the Quartering Act of 1765. That law required colonials to provide provisions and housing to British troops stationed there. It hit New York hardest because New York was the headquarters of the British force in the colonies. Having been caught in a trap of their own making, the colonials changed tack. They drew distinctions between tariffs for revenue and tariffs to regulate trade. The latter were acceptable; the former were not. Since the Townshend Duties were for revenue, colonists rose up against them. They rekindled the Non-Importation movement, and colonial shippers and merchants, such as John Hancock, stepped up their smuggling activities. The new taxes also caused opponents of the laws to split over tactics. The moderate view was represented by John Dickinson in his Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer. Dickinson was a wealthy planter and a true patriot of the colonies, but he feared British power and did not want to make matters worse by resorting to mobism. He repeated the arguments of the Declaration of Rights in a clearer and more plain-spoken manner. But he stopped short of advocating violence. “The cause of Liberty,” he exclaimed, “is a cause of too much dignity to be sullied by turbulence and tumult.” Outraged by the new taxes, many colonials again called for boycotts. Among the most aggressive were the Sons of Liberty in Massachusetts, led by Samuel Adams. In 1768, Adams and James Otis wrote the Massachusetts Circular Letter (open letter) attacking Parliament’s taxing and calling on other colonies to join Massachusetts in opposition. Meanwhile, the Royal Governor of Massachusetts dissolved the assembly. But soon the answers to the letter started arriving: the colonies supported Massachusetts. In June 1768, tensions grew as the British tried to make an example of John Hancock. Hancock’s ship, Liberty, arrived at port with a cargo of wine. Hancock declared just a part of the cargo for customs officers. The Royal Navy seized the ship for non-payment of taxes. That night, a mob collected protesting the seizure; it threw rocks at customs officers and burned a customs boat. In September, 4,000 British Regulars arrived to maintain order in Boston. According to Parliament, Massachusetts was in rebellion. Boston Massacre “We have entertained a great variety of phrases to avoid calling this sort of people a mob. Some call them shavers, some call them geniuses. The plain English is, gentlemen, [it was] most probably a motley rabble of saucy boys, Negroes and mulattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jackers. And why should we scruple to call such a people a mob, I can’t conceive, unless the name is too respectable for them.” John Adams The issue festered until the winter of 1770. On the cold, moonlit evening of March 5th, a group of young men began taunting a sentry with snowballs at the Customs House in Boston. Soon the snowballs turned to ice, rocks, and coal lumps. The group became a mob as several hundred converged on the Customs House. Soldiers reinforced the sentry. As the mob bashed sticks together and threw whatever was at hand, the platoon fired into the crowd. By the time the dust cleared, five colonials lay dead, including an African American dockworker named Crispus Attucks, often considered the first casualty of the Revolution. Samuel Adams called the killings “bloody butchery” and Paul Revere illustrated the event. “Unhappy Boston! See thy sons deplore Thy hallowed walks besmear’d with guiltless gore. While faithless Preston and his savage bands, With murderous rancor stretch their bloody hands; Like fierce barbarians grinning o’er their prey, Approve the carnage and enjoy the day. If scalding drops, from rage, from anguish wrung, If speechless sorrows lab’ring for a tongue, Or if a weeping world can aught appease The plaintiff ghosts of victims such as these; The patriot’s copious tears for each are shed, A glorious tribute which enbalms the dead. But now, Fate summons to that awful goal, Where justice strips the murderer from his soul Should venal C____ts, the scandal of the land, Snatch the relentless villain from her hand, Keen execrations on this plate enscrib’d Shall reach a judge who never can be bribed.” The Boston Massacre scared both sides. Samuels Adams and Joseph Warren continued to organize resistance, reviving the Committee of Correspondence. And in Virginia, Patrick Henry and others, including Thomas Jefferson, created a Committee of Correspondence. But as a matter, tensions and conditions eased between 1770 and 1773. Britain assisted in easing tensions by repealing the duties on all goods, except tea. The taxes on tea caused Bostonians to boycott tea, causing debt for the British East India Company. The company lobbied Parliament for assistance. The Tea Act of 1773 eliminated the duty on the company’s tea, enabling the company to sell tea at a lower price than Hancock. Hancock and his protégé, Adams, were upset by the new arrangement. The Boston Tea Party On December 16th, 1773, the issue came to a head. Three ships carrying cargoes of tea were to land at Griffin’s Wharf. That night, Adams’ Sons of Liberty met to organize. Some dressed as Mohawk Indians others as women, they boarded the ships and tossed 45 tons of tea into the harbor. The British response was quick and severe. Parliament enacted a series of laws, known as the Coercive Acts because they meant to coerce better behavior from Massachusetts, or as the Intolerable Acts because the colonials found they could not tolerate them. 1. Boston Port Act: closed the port of Boston to all traffic and trade. 2. Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice: moved all trials to Admiralty Courts in Halifax. 3. Massachusetts Government Act: the Royal Governor appoints the colonial council and law enforcement officers. 4. Quartering Act of 1774, which expanded the requirement to provide room and board for British soldiers, including in private homes, if necessary. Around the same time, Parliament also passed the Quebec Act. It set up unrepresentative government in Quebec; gave a privileged position to the Roman Catholic Church in the province; and expanded Quebec’s boundary west, encircling the Colonies. The Colonies saw it as the thin edge of a wedge to end representative government and the Reformed Protestant religion in the colonies. The Intolerable Acts began a tumbling snowball that within two years led to American independence. In September 1774, delegates from each of the Colonies, except Georgia, met in the First Continental Congress. Among the delegates were John and Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, George Washington, John Dickinson, Edmund Rutledge of South Carolina, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and John Jay of New York. Congress debated but rejected a plan that would have created the Continental Association, similar to Franklin’s Plan of Union. It approved an embargo on all British goods. And it accepted an idea from Thomas Jefferson’s Summary View of the Rights of British America that only the King, not Parliament, had power to govern the colonies. Known as the Dominion Theory, it intended to bypass Parliament and plead its case directly to the crown. It was a potentially dangerous argument, because if the king favored Parliament, then the colonies would have little room for further maneuvering. The Congress adjourned in October with orders to meet again in May 1775. Along with the Coercive Acts, Britain sent a military governor General Thomas Gage to Massachusetts. In October 1774, Massachusetts defied Gage and met in assembly. It named John Hancock head of the Committee on Safety. The Committee was empowered to call up a colonial militia. Hancock organized special units of the militia in to squads known as Minutemen. From this point onward, Massachusetts truly is in rebellion. Battle of Lexington and Concord: The Shot Heard ‘Round the World: On April 19th, the redcoats met the Minutemen on Lexington Green, someone fired a shot and war began. With shots finally fired, New England prepared for war, but the other colonies were less united in their response. In New York, Patriots organized the militia, while loyalists asked Gage to suspend further attacks until orders came from England. New Jersey was split between patriots and Tories, led by Governor William Franklin (illegitimate son of Ben Franklin). Quaker Pennsylvania divided between pacifists and fighters, while the rest of the colony divided into Patriots, led by Franklin, and Loyalists, led by Dickinson. In the Chesapeake, Maryland opposed revolution, while Virginia (especially Patrick Henry) supported it. A month before Lexington, Henry urged the House of Burgesses to organize a militia, giving his oft-quoted speech, “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Loyalism was stronger in the Lower South, particularly in the back-country among the Scots-Irish who distrusted the Low Country planters. But a strong patriot contingent also existed in the Carolinas, as well as Georgia. On May 20th, Mecklenburg County issued the “Resolves” and declared its independence: “We do hereby declare ourselves a free and independent people; are, and of right ought to be a sovereign and self-governing association, under the control of no power, other than that of our God and . . . Congress: To the maintenance of which Independence we solemnly pledge to each other our mutual co-operation, our Lives, our Fortunes, and our most Sacred Honor.” “There is something charming to me in the conduct of Washington: a gentleman of one of the first fortunes upon the continent, leaving his delicious retirement, his family and friends, sacrificing his ease and hazarding all in the cause of his country.” John Adams Second Continental Congress: Beginning in May 1775, it was the first to include delegates from all of the colonies. Most wanted to avoid further conflict, but prepared for war. In June, it named George Washington Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775): First major battle of the war. The British won the battle north of Boston, but it was a pyrrhic victory; they suffered 1,054 casualties. After Bunker Hill, John Dickenson tried once again to restore peace. He wrote the “Olive Branch Petition,” sent to England on July 8th, 1775. We beg leave further to assure your Majesty that notwithstanding the sufferings of your loyal colonists during the course of the present controversy, our breasts retain too tender a regard for the kingdom from which we derive our origin to request such a reconciliation as might in any manner be inconsistent with her dignity or her welfare. . . . The apprehensions that now oppress our hearts with unspeakable grief, being once removed, your Majesty will find your faithful subjects on this continent ready and willing at all times, as they ever have been with their lives and fortunes to assert and maintain the rights and interests of your Majesty and of our Mother Country. We beseech your Majesty . . . with all humility submitting to your Majesty's wise consideration . . . that measures be taken for preventing the further destruction of the lives of your Majesty's subjects; and that such statutes as more immediately distress any of your Majesty's colonies be repealed: For by such arrangements as your Majesty's wisdom can form for collecting the united sense of your American people, we are convinced, your Majesty would receive such satisfactory proofs of the disposition of the colonists towards their sovereign and the parent state, . . . becoming the most dutiful subjects and the most affectionate colonists. Thomas Jefferson wrote a companion piece that explained the action of forming colonial militias: On the Necessity of Taking Up Arms, July 1775. “Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great, and, if necessary, foreign assistance is undoubtedly attainable. . . . With hearts fortified with these animating reflections, we most solemnly, before God and the world, declare, that, exerting the utmost energy of those powers, . . . we will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverence, employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to die freemen rather than to live slaves.” Lest this declaration should disquiet the minds of our friends and fellow-subjects in any part of the empire, we assure them that we mean not to dissolve that union which has so long and so happily subsisted between us, and which we sincerely wish to see restored. -- Necessity has not yet driven us into that desperate measure, or induced us to excite any other nation to war against them. -- We have not raised armies with ambitious designs of . . . establishing independent states. [I]n defence of the freedom that is our birthright . . . against violence actually offered, we have taken up arms. We shall lay them down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the aggressors, and all danger of their being renewed shall be removed, and not before. Ironically, the Olive Branch Petition reduced the colonies’ ability to negotiate because if the king rejected it, then there would be little for the colonies to do but either give in or become independent. News of Bunker Hill arrived in England just before the petition. Many in Britain also wanted conciliation, but the vote to accept the petition lost 86 to 33. In August, King George III called the colonials rebels and rejected the petition. Instead, he turned to Europe for troops. Several German states complied, most notably that of Hesse, which supplied 13,000 Hessian mercenaries. “I HAVE never met with a man, either in England or America, who hath not confessed his opinion, that a separation between the countries would take place one time or other: And there is no instance in which we have shown less judgment, than in endeavoring to describe, what we call, the ripeness or fitness of the continent for independence.” Tom Paine Common Sense (1776): Pamphlet written by radical English Quaker Tom Paine and published in Philadelphia in January 1776. It argued that it made no sense for the colonies to stay part of England. Its fiery language and clear reasoning helped convince the large segment of undecided to join the independence movement Paine argued succinctly not just for independence, but for an open declaration explaining our reasoning to other European powers. To CONCLUDE, . . . many strong and striking reasons may be given to show that nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independence. Some of which are, It is the custom of Nations, when any two are at war, for some other powers to step in as mediators; But while America calls herself the subject of Great Britain, no power, however well disposed she may be, can offer her mediation. Wherefore, in our present state we may quarrel on for ever. While we profess ourselves the subjects of Britain, we must, in the eyes of foreign nations, be considered as Rebels. [Last]ly. — Were a manifesto to be published, and despatched to foreign Courts, setting forth the miseries we have endured, and the peaceful methods which we have ineffectually used for redress; . . . at the same time, assuring all such Courts of our peaceable disposition towards them, and of our desire of entering into trade with them; such a memorial would produce more good effects to this Continent than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain. Under our present denomination of British subjects, we [cannot be] heard abroad; the custom of all Courts is against us, and will be so, until by an independence we take rank with other nations. Halifax Resolves: North Carolina was the first “province” to declare its support for independence. In April 1776, the North Carolina Provincial Congress met in Halifax County to debate responses to events and to decide what instructions to give its delegates to the Second Continental Congress. On April 12th, its 83 delegates unanimously agreed to permit NC’s delegates to support independence. The Resolves did not, however, give NC’s delegation permission to introduce an independence resolution at the Philadelphia meeting. Virginia Resolves: In early June 1776, Richard Henry Lee, the leading delegate from Virginia offered a resolution for independence. A unanimous vote of all provinces was required for passage. To overcome opposition, the Congress decided to draw up a declaration of the theory and causes of why the United States should be free from British rule. On July 2nd, amendments to the declaration were complete and the unanimous vote taken. Declaration of Independence: Founding document of the U.S. signed on July 4, 1776. It was written by committee (Ben Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston) with most of the work done by Jefferson: the document is in four parts: 1. a preamble, offering an introduction as to the purpose of the document 2. explanation of natural rights, based on Locke's “social contract:” life, liberty, pursuit of happiness 3. presentation of grievances against King George III 4. statement of intent, i.e. says that the colonies are sovereign and independent Declaration of Independence, Paragraph 2: The Lockean Reasoning “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive to these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. --Such has been the patient sufferance of these colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former systems of government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these states. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.” Yorktown (August – October 1781): Just miles from Jamestown, the U.S., under the command of George Washington and with considerable help from the French, defeated the British after a long siege and Cornwallis surrendered, ending the war. Treaty of Paris (September 1783): Treaty ending the War of Independence: with it the U.S. gained control of all the land east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of British Canada. In November, the British evacuated New York City. A month later, General Washington resigned his commission as Commander of Continental Army, showing that a civilian government would run the U.S.