PowerPoint Presentation - Iredell

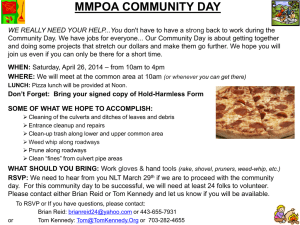

advertisement

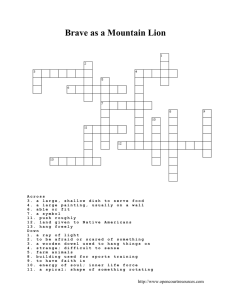

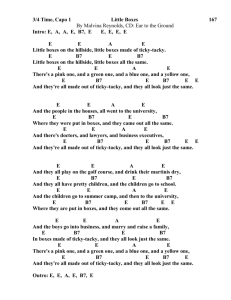

Goal #11: Recovery, Prosperity, and Turmoil (1945-1980), trace economic, political, and social developments and assess their significance for Americans during this period. 11.01: Describe the effects of the Cold War on economic, political, and social life in America 11.02: Trace major events of the Civil Rights Movement and evaluate its impact 11.03: Identify other major social movements and evaluate their impact on U.S. society 11.04: Identify the causes of U.S. involvement in Vietnam and examine how the involvement affected society 11.05: Examine how technological innovations have impacted American life 11.06: Identify significant political events and personalities and assess their social and political effects The World's Economic Superpower Emerges Conformity: to be like everybody else – the post-war period is seen as a time of conformity when several things pressured Americans not to express their individualism or to act in ways that challenged the dominant culture, a culture that stressed consumerism, materialism, traditional gender roles and morality. One reason for this is the prosperity that the nation witnessed in the two decades following WWII. After years of hardship, Americans could afford to buy things again. Added to that, a firm belief that the Great Depression was caused by a lack of consumer power (demand-side economics) took hold. It was good to buy “things” (cars, refrigerators, televisions): good because it was fun and good because it kept people working making those things and kept the economy humming. Another reason was the rise of suburbia. All the homes looked alike; you could walk into a new friend’s suburban home that you had never visited before and know the basic floor plan (or notice how it differed from your house) An impression of equality emerged – you were basically the same as your neighbor. But when your neighbor bought something new, you might have sensed that you were falling behind; so you had to get that new thing, too. You had to “keep up with the Joneses.” The media helped foster these ideas, through advertising or consumer magazines. The political culture also created a culture of conformity. In an era of “Red Scare,” it was dangerous to hold different beliefs: you could lose your job or be ostracized from the community. Such stifling of individualism helps explain not only the culture of the 1950s, but also the reaction to it in the 1960s and 1970s. The 1955 film, Rebel Without a Cause, exemplifies the tension over conformity and individual expression. In it, the young superstar James Dean feels constricted by his middle-class parents and upbringing. He has every material thing he could want and his parents love him and treat him well, but he is dissatisfied. He needs to find his own character. But the dominant culture dismisses his rebelliousness. Life is good (better than it was for his parents in the Depression and War). He has no “cause.” The 1960s and 1970s offer innumerable “causes” for which to rebel. Ticky-Tacky Suburban Society: The Culture of Conformity, 1945-1964 “The Fifties:” In 1957, U.S. News & World Report called the previous ten years a “decade of miracles.” The U.S. had emerged as the world’s sole economic superpower. America was “a nation on the move” with “millions of babies . . . millions of pupils . . . millions of jobs . . . millions of households . . . [and for them] millions of new homes in new cities.” The U.S. comprised 7% of the world’s population, but held 42% of the world’s income and produced 50% of the world’s manufacturing output—43% of electricity, 57% of steel, 62% of oil, 80% of automobiles. It held 75% of the world’s gold. One big reason behind the boom was the continued spending of the federal government to avoid a return to the Great Depression. In 1950, government expenditures reached $43 billion, more than four times 1939 levels. Spending included guaranteed mortgage loans, on highway construction, on medical and scientific advancements, and the “militaryindustrial complex” of new weapons systems. Not all Americans shared in the bounty, of course, and anxiety over the struggle against Communism abroad and at home made the decade less than perfect. But economically, as a nation, there is no question that the U.S. had become the world’s economic superpower. The Baby Boom: The postwar years (1946-1962) witnessed the largest demographic bubble in U.S. history—70 million babies, almost two-fifths of the 1960 population of 190 million. A rise could be seen as early as 1942, with the so called “furlough babies,” but birth rates after the war rose from less than 20 per 1,000 in the 1930s to nearly 27 per 1,000 in 1947, the biggest year. The boom resulted not just from soldiers returning home from overseas, but from a sizeable increase in marriages among a 1920s generation who delayed marriage because of the Depression and war and from an increase in marriages among younger people (early twenties) caused in part by rising standards of living. It did not occur because couples were having more children, rather because more couples were having children. The wealth of the era, the leisure time afforded to the young, and the rise in population created a specialized “youth market” of music and movies in the 1950s and 1960s. The boom ended with the advent of the “birth-control pill” in the early 1960s, as couples married later, and as divorce became more accepted. The G.I. Bill: Shortly after D-Day, Congress enacted the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the “G.I. Bill of Rights” – G.I. stands for “general issue.” The Act stipulated that any veteran who had served at least 90 days in the military after September 1940 had the right to the following benefits: 1. access to a job finding program 2. unemployment benefits for a year 3. access to discount home mortgage loans 4. “education and training.” The last “right” became the most significant over time – veterans received up to four years of paid, full-time education, including money for college. By 1956, about 8 million veterans had taken advantage of the opportunities, including more than 2 million who went to college or university. The WWII generation was the first to have so many get beyond a high school education. The WWII law was the first to include all veterans; earlier benefits packages served only those disabled by wounds in war. Later “bills of rights” expanded on the program after each war. Taft-Hartley Act of 1947: The Labor Management Relations Act, it represents the Republican party’s alternative to the pro-Labor Wagner Labor Relations Act of the New Deal. It was shepherded through the Senate by Republican leader Robert Taft of Ohio. It gave more explicit protection to some forms of labor organization, but it also protected workers who did not wish to join a union—rejecting the “closed shop.” It expanded the federal government’s role in mediating labor disputes, including enabling the National Labor Relations Board to enjoin strikes in “vital industries.” It restricted the participation of members of the Communist Party in labor activities. President Truman vetoed the bill, but the Republican-dominated Congress overrode his veto. The lasting result of the law was to limit Labor’s ability to coerce membership, reducing Labor’s power to organize, and to ensure organized Labor would remain a major constituency in the Democratic Party. Election of 1948: The most surprising election in U.S. history. The Republican Thomas Dewey was so sure he would win that he stopped campaigning in August. The reason he was so sure was that the Democratic Party was split into three factions: the center—led by POTUS Harry Truman; the left (the Progressives) – led by former Vice-POTUS Henry Wallace; and the conservatives and South (States Rights Democratic Party, a.k.a. the Dixiecrats) led by Strom Thurmond. Truman, however, continued to campaign and ending up winning the Labor vote and enough of the urban black vote to win Illinois, Ohio, and California. Truman won the election. Election of 1948 Fair Deal: Harry Truman’s domestic policy agenda for his second term, building on the New Deal and the large-scale entry of African Americans into the Democratic party coalition. It called for: repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act and a raise in the minimum wage (to carry out the interests of Labor); expansion of public works utility projects and federal housing projects (to grease the economy); offering federal aid to education for the first time; expanding the social safety net by broadening Social Security and creating a health-care program for the elderly; and, for African American voters, civil rights (including desegregating the military). Only housing, Social Security, and the minimum wages made it into law because a coalition of Republicans and conservative southern Democrats blocked passage of other parts of the Fair Deal. Where Truman had control, as with desegregating the military, he was able to act. “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a Communist. He has too much to do.” – William Levitt Levittown: First mass suburban tract built after WWII. Using construction techniques developed to meet the need for temporary housing during the war, William Levitt and Sons created an assembly line approach to construction that led to “modular housing.” The houses were small by today’s standards (c. 1200 square feet) and in two styles, a Cape Cod and a Ranch bungalow. The Cape Cod started at $6,990; the ranch slightly higher. Now, according to a Levittown resident, “you can’t get a house [here] for less than $400,000.” Levitt divided the building process into steps, performed in sequence by a crew that repeated its same tasks on each home. Levitt claimed to finish a house every fifteen minutes. The first Levittown, on Long Island, New York, had 17,500 houses and 82,000 residents. Along with new construction techniques, postwar homebuilders and buyers took advantage of new tax rules and low-interest loans sponsored by the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration to create the post-war housing boom. “Little Boxes” Malvina Reynolds Little boxes on the hillside, Little boxes made of ticky-tacky, Little boxes, little boxes, Little boxes all the same. There’s a green one and a pink one And a blue one and a yellow one And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky And they all look just the same And they all play on the golf course And drink their martinis dry And they all have pretty children And the children go to school, And they children go to summer camp And then to the university And they all get put in boxes And they all come out the same And the people in the houses All go to the university And they all get put in boxes, Little boxes all the same And there’s doctors and there’s lawyers And business executives And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky And they all look just the same And the boy’s go into business And marry and raise a family And they all get put in boxes Little boxes all the same There’s a green one and a pink one And a blue one and a yellow one And they’re all made out of ticky-tacky And they all look just the same “I Like Ike”: Truman’s problems in Korea and the stress of his second term kept him from another run for the presidency. He talked Illinois Governor Adlai E. Stevenson II into running and Stevenson won the nomination. Republicans, meanwhile, considered Robert Taft (“Mr. Republican”), but searched for a more likely winner. They found Dwight Eisenhower. As hero of WWII, Eisenhower was a shoo-in with the public. The only question was whether conservative Republicans could be coaxed along. They were, with the selection of Richard M. Nixon as vice-presidential candidate. A political moderate, Eisenhower did not intend to dismantle the New Deal. He did not intend to do much of anything and that was what a conforming America wanted. Economic prosperity continued thanks in part to major public works projects. Although his was essentially a successful presidency, Eisenhower’s biggest oversight as POTUS was his slow support for the growing Civil Rights Movement. He had a settling influence on the American psyche despite the anxieties of the Cold War. And so is considered an “Above Average” POTUS and ranked 9th among presidents in recent polls of historians. “The interstate highway system is a wonderful thing. It makes it possible to go from coast to coast without seeing anything or meeting anybody. If the United States interests you, stay off the interstates.” Charles Kuralt Interstate Highway System: Inspired by the German Autobahn, created under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and championed by President Eisenhower, it is a limited-access superhighway system crisscrossing the U.S. It serves a dual-purpose: to facilitate car and truck travel (commerce), and to increase national security by providing roads that could sustain tanks and military trucks. Costing an estimated $129 Billions, it has transformed the American economy, changed the relationship of the federal government to the states as relates to transfer payments and power, reshaped American cities, altered the landscape, and even changed American culture. Along with radio, television, other technology, and the growth of the federal government, the Interstate Highway System united the country and helped to create a more uniform American culture. Polio Vaccine: Invented by Jonas Salk in 1952, it became available in the mid-1950s after several clinical trials. It consisted of an injected dose of killed polio virus. Albert Sabin produced an oral vaccine in 1962. The research was funded publicly and through the work of such organizations as the March of Dimes and the vaccine all but eliminated child paralysis (poliomyelitis), a disease that affected 58,000 children in 1952 (killing 1,400) and had paralyzed Franklin D. Roosevelt. By 1962, there were only 910 recorded cases in the U.S. Ending polio significantly boosted other disease prevention research and gave hope that science would eliminate other childhood diseases, as well as cancer, heart disease, and stroke Transistors: Semiconductors used for amplification and switching—the key components in modern electronics. Using less power and being much smaller than vacuum tubes, they facilitated portable electronic devices, such as transistor radios first developed by Texas Instruments in 1954. The pre-transistor portable radio was about the size of a notebook computer and contained several heavy batteries. By comparison, the “transistor,” as it became known, was small and operated off a single 9V battery. Transistors became popular with youth in the early sixties, when their price came down from its original $50. Television: Although invented much earlier, television receivers were not marketed to any great extent before the end of WWII (besides there was nothing to watch). In 1949, 2.3% of American homes had black-and-white sets on which to watch the most popular viewing of the day—wrestling. By 1962, 90% of homes had at least one TV and by the mid-1960s sets were color. In between, the two major radio networks, CBS and NBC, transformed many of their popular radio shows into television shows (Amos and Andy, The Lone Ranger, etc.) many shown “live.” New TV stars established themselves—none bigger than Lucille Ball on I Love Lucy. Many big-time recording stars had fifteen minute musical programs—Perry Como and Nat King Cole. Game shows were extremely popular, at least before being discredited in the “Quiz Show Scandal” where viewers of Twenty-One and $64,000 Question discovered that contestants had been given the answers before hand. And viewers became riveted by news programs and Congressional hearings involving McCarthy’s Red Scare and the investigations into organized crime. Finally, while important and cutting-edge dramas played on programs such as Playhouse 90, most shows were family fare – light, moralist, and suburban – blandly capturing the “American Dream.” CinemaScope: One of the new film technologies developed in the early 1950s to counter competition from television. It reformatted film ratios to enable “widescreen” projection. Other processes include Vistavision (similar to CinemaScope); 3-D (where one sensed three dimensions on screen, action coming right at you, if you wore bi-colored plastic glasses) and Cinerama (a complicated playback involving three projectors combining three different segments of the same shot. The last two are seldom used today, but “widescreen” and its descendent “70 mm” are commonplace now. Hootenanny: In the late1950s, an acoustic folk music revival emerged to challenge the frivolousness of “pop music” and rock-and-roll. It built on work by “old folkies”, such as Woody Guthrie and The Weavers (notably Pete Seeger who was blacklisted for membership in the Communist Party USA). The breakthrough act of the revival was The Kingston Trio whose “Tom Dooley” (about the hanging of Tom Dula in Statesville for murder) exploded on the charts in 1959. For the next five years, folk music merged with the civil rights movement and competed with rock-and-roll for the youth market with artists, such as Peter, Paul, and Mary, and Phil Ochs. It reached a new level in Bob Dylan. “Tom Dooley” Frank Warner/John Lomax/Alan Lomax (Spoken recitation over musical accompaniment) Throughout history, there have been many songs written about the eternal triangle. This next one tells the story of Mister Grayson, a beautiful woman, and a condemned man named Tom Dooley. When the sun rises tomorrow, Tom Dooley must hang. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Hang down your head and cry. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Poor boy, you're bound to die. I met her on the mountain. There I took her life. Met her on the mountain. Stabbed her with my knife. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Hang down your head and cry. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Poor boy, you're bound to die. This time tomorrow. Reckon where I'll be. Hadn't-a been for Grayson, I'd-a been in Tennessee. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Hang down your head and cry. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Poor boy, you're bound to die. This time tomorrow. Reckon where I'll be. Down in some lonesome valley hangin' from a white oak tree. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Hang down your head and cry. Hang down your head, Tom Dooley. Poor boy, you're bound to die. The Beats: Group of writers centered in San Francisco that led the bohemian antiestablishment movement that eventually developed in to the“counter culture”. Their followers became known as “Beatniks” or “Hipsters.” Coordinated by Lawrence Ferlinghetti (author of the most popular American book of poetry, A Coney Island of the Mind), through his City Lights Book Store, they erupted on the literary scene in the mid-1950s with the publication of a poetry collection by Allen Ginsberg, “Howl”. The book scandalized publishing because of its shocking language and explicit sexuality and Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg were indicted on obscenity charges. When the local artistic community came to their defense, they were acquitted. The case opened the way for new and more provocative works to follow. Although other writers had success, the most successful was Jack Kerouac, whose books On the Road and Dharma Bums remain icons of 1950s rebellion. Several of the Beats got caught up in experimentation with drugs, particularly LSD, in the early and mid-1960s (William S. Burroughs, Ken Kesey, the Grateful Dead). Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti stayed at the center of the counterculture when San Francisco, specifically Haight-Ashbury, became the Mecca for hippies after 1965. Camelot, 1961-1963 “Ask not”: John F. Kennedy’s presidency represented, as he said, “a passing of the torch” from the WWI generation (Eisenhower) to the WWII generation. His New Frontier program was meant to spark the imagination of young people by inviting them to volunteer to contribute to society in various ways. “Ask not what your country can do for you,” he declared in his inaugural address, “ask what you can do for your country.” Assassination of John F. Kennedy: On November 22, 1963, JFK traveled to Texas to raise money for the 1964 election. As JFK rode through Dallas in an open limousine, Lee Harvey Oswald shot and killed him. A couple of days after the murder, Jack Ruby, claiming he wanted to avenge Kennedy, killed Oswald. Oswald’s quick death left many questions unanswered and led to speculation of a conspiracy "Camelot": After the murder and funeral of President Kennedy, a mythology developed that came to overwhelm the reality of the Kennedy years. In death, Kennedy became more universally popular in America than he was in life. He became the symbol of hope that, as the U.S. descended into disorder and careened from one disaster to another over the next twenty years, became a symbol of lost innocence and a dream destroyed. Chief among the mythmakers were his advisers, his staff, and his family. Shortly after the assassination, historian and Kennedy adviser Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., asked Jacqueline Kennedy what life was like in the JKF White House. Recalling the favorite Broadway musical of the day, she said that it was like Camelot" -- "In short there's simply not a more congenial spot for happ'ly-ever-aftering than here in Camelot." The myth stuck. “The British Invasion”: In February 1964, as the U.S. dealt with JFK’s murder, the Beatles (John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Ringo Starr) landed in New York to play the Ed Sullivan Show. The crowd (mostly screaming girls) greeting them at the airport was the biggest thing rock music had seen since Elvis Presley broke on the scene. Over the next year, the Beatles dominated American culture (music, dress, hair, even movies). After them, came British acts of varying quality and popularity— from giants (Rolling Stones, The Who, Eric Clapton) to the big and then gone (Gerry and the Pacemakers, Dave Clark Five, Herman’s Hermits, Donovan, The Animals)—changing the face of popular music. The synergy of the British invasion, America’s musical response, the youth market, drugs, and the Vietnam War helped expand the counterculture on both sides of the Atlantic.