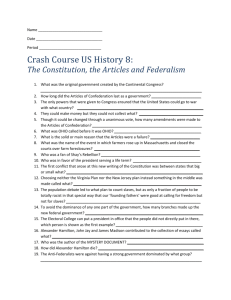

Angelina Lester, an ex

advertisement

The African-American Experience in Ohio 1850-1920 http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/S?ammem/aaeo:@field(SUBJ+@od1(Underground+railroad)) “If you come to us and are hungry, we will feed you; if thirsty, we will give you drink; if sick, we will minister to your necessities; if in prison, we will visit you; if you need a hiding place from the pursuer, we will provide one that even bloodhounds will not scent out.” -Credo of the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1843 Slavery is a Hard Foe to Battle Written by Judson, 1855 I looked to the South and I looked to the West And I saw old Slavery a-coming With four Northern dough faces hitched up in front Driving freedom to the other side of Jordan Then take off coats and roll up sleeves Slavery is a hard foe to battle; Then take off coats and roll up sleeves O’ Slavery is a hard foe to battle I believe. Am I not a man and a brother? Date Created/Published: 1837. Summary: The large, bold woodcut image of a male slave in chains appears on the 1837 broadside publication of John Greenleaf Whittier's antislavery poem, "Our Countrymen in Chains." The design was originally adopted as the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England in the 1780s, and appeared on several medallions for the society made by Josiah Wedgwood as early as 1787. Reynolds Political Map of the United States, designed to exhibit the comparative Area of the free and slave states New York and Chicago, 1856 Map The underground railroad / Chas. T. Webber. c1893. African Americans in wagon and on foot, escaping from slavery. Ashtabula Harbor Ashtabula Harbor, from which fugitive slaves were sent across Lake Erie to Canada. The warehouse on the left was a hiding place for the fugitives. Aaron L. Bendict's House and Barn Photograph of Aaron L. Benedict's house and barn, Underground Railroad station, Alum Creek Friends' Settlement (Marengo), Morrow County, Ohio. Barn of Seth Marshall Photograph of the barn on the Seth Marshall homestead in Painesville, Lake County, Ohio. The barn was a hiding place for fugitive slaves. John Parker 1827 - 1900 Born enslaved in Virginia, Parker was sold away from his mother at age eight and forced to walk in a line of chained slaves from Virginia to Alabama. After several unsuccessful attempts, he finally bought his freedom with the money he earned doing extra work as a skilled craftsman. Parker moved to Cincinnati and then to Ripley, where he became one of the most daring slave rescuers of the period. Not content to wait for runaways to make their way to the Ohio side of the river, Parker actually "invaded" Kentucky farms at night and brought over to Ripley hundreds of slaves. He kept records of those he had guided towards freedom, but he destroyed the notes in 1850 after realizing how the Fugitive Slave Law threatened his home, his business, and his family's future. John Rankin (1793-1886) Ripley, Ohio, was a minister and abolitionist. His first congregation recoiled from his anti-slavery doctrine and drove him off. Rankin and his large family moved to Ripley where they lived as public abolitionists who enlisted several hundred Ohio residents against slavery. Bust of John Rankin by Ellen Rankin Copp John Rankin House (Ripley, Ohio) Photograph of the restored John Rankin House in Ripley, Ohio. The Rankin House is one of the sites operated by the Ohio Historical Society. "Freedom Stairway" Photograph of the "freedom stairway", the steps leading from the Ohio River to the John Rankin House, Ripley, Ohio. View of the Ohio River and downtown Ripley, Ohio from the John Rankin House. Photograph by Richard Cooper Alfred Murphy, an ex-slave Photograph of Alfred Murphy, an ex-slave who lived in Columbus, Franklin County, Ohio. "Never Too Old to Learn!" That's the slogan of this 105 year old ex-slave who was a pupil in a literacy class conducted by the WPA in Columbus, Ohio. David Wilborn, an ex-slave Photograph of David Wilborn, an ex-slave who lived at 220 Fair Street in Springfield, Clark County, Ohio. Charles Green, an ex-slave Photograph of Charles Green, an ex-slave who lived at 231 Buxton Avenue in Springfield, Clark County, Ohio, District 1. Life In Slavery: Sarah Ashley, 93, was born in Mississippi I used to have to pick cotton and sometimes I pick 300 pound and tote it a mile to the cotton house. Some pick 300 to 800 pound cotton and have to tote the bag the whole mile to the gin. If they didn’t do they work they get whip till they have blister on them. Then if they didn’t do it, the man on a horse goes gown the rows and whip with a paddle make with holes in it and bust the blisters. I never get whip, because I always get my 300 pound. Us have to go early to do that, when the horn goes early, before daylight. Us have to take the victuals in the bucket to the field. Us never got enough to eat, so us keeps stealing stuff. Us has to. They give us the pack of meal to last the week and two, three pound back on in chunk. Us never have flour or sugar, just cornmeal and the meat and potatoes. The [slaves] have the big box under the fireplace, where they keep all the pick and chicken what they steal, down in salt. Sarah Ashley Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington Angelina Lester, an ex-slave Photograph of Angeline Lester, an ex-slave who lived Youngstown, Mahoning County, Ohio, District 5. In 1834, Jermain Loguen (circa 1813-1868), a Tennessee slave (otherwise known as Jarm Logue), boldly rode out of Tennessee and slavery, and continued to ride until he reached Canada and freedom. Loguen and his wife received fugitives ceaselessly, at all hours of the night and day, and even while their daughter lay fatally ill. Loguen agitated for jobs for blacks. Loguen established a school and a church wherever he could for emancipated slaves. Elsie Ross, an ex-slave Photograph of Elsie Ross, an ex-slave who lived at 300 Sprague Street in Dayton, Montgomery County, Ohio, District 2. Punishment: Walter Calloway, Birmingham, Alabama Master John had a big plantation and lots of slaves. They treated us pretty good, but we had to work hard. Time I was ten years old I was making a regular hand behind the plow. Oh, yes Sir, Master John good enough to us and we get plenty to eat, but he had a overseer name Green Bush what sure whip us if we don’t do to suit him. Yes Sir, he mighty rough with us but he didn’t do the whipping himself. He had a big black boy name Mose, mean as the devil and strong as a ox, and the overseer let him do all the whipping. And, man, he could sure lay on that rawhide lash. Walter Calloway Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington Sarah Frances Shaw Graves Age 87 "I was born March 23, 1850 in Kentucky, somewhere near Louisville. I am goin' on 88 years right now. (1937). I was brought to Missouri when I was six months old, along with my mama, who was a slave owned by a man named Shaw, who had allotted her to a man named Jimmie Graves, who came to Missouri to live with his daughter Emily Graves Crowdes. I always lived with Emily Crowdes." Harriet Tubman 1822 - 1913 When, as a young child on a plantation in Eastern Maryland, Tubman tried to protect another slave, she suffered a head injury that led to sudden blackouts throughout her life. On her first escape, Tubman trekked through the woods at night, found shelter and aid from free Blacks and Quakers, and eventually reached freedom in Philadelphia to align with William Still and the Vigilance Committee. After hearing that her niece and children would soon be sold, Tubman arranged to meet them in Baltimore and usher them North to freedom. It was the first of some thirteen trips during which Tubman guided approximately 50 to 70 people to freedom. Tubman spoke often before antislavery gatherings detailing her experiences. She was never captured, and went on to serve as a spy, scout, and nurse for the Union Army. When the government refused to give her a pension for her wartime service, Tubman sold vegetables and fruit door-to-door and lived on the proceeds from her biography. (Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Broadside Collection, portfolio 65, no. 16). BETSEY ESCAPES TENNESSEE Arkansas Gazette October 4, 1825 (October 11, 1825) $30 REWARD RANAWAY from the subscriber, living near Lawrenceburg, Lawrence county (Ten) about the first of August last, a black NEGRO WOMAN named BETSEY, about 15 years of age, spare made stammers a little in her speech at times, and when walking makes long steps--no particular mark recollected. The above reward of Thirty Dollars will be given if taken out of the State, and confined so I get her, and Twenty Dollars if taken in the state and confined so I get her. PETER WINN September 3d, 1825 ESCAPE OF JACK Arkansas Gazette December 2, 1820 (January 6, 1821) $150 Reward RAN away from my plantation, Lincoln county, Tennessee, on the first day of August last, a Negro man named JACK. He is about 6 feet high, a dark mulatto, broad shoulders, rather inclined to be round, high cheek bones, thin jawed, thin lips, large hands and feet, and rather an impediment in his speech, dejected countenance when spoken to, and very fond of spirituous liquors, a large scar on his breast, on the left side, and under the left nipple, and has been passing by the name of DAVE; he is a tolerable good shoemaker, and an excellent hand at the whip-saw. Any person apprehending said fellow and confining him in any jail in Tennessee or Kentucky, shall have the above reward, or one hundred dollars, if confined to any jail in the United States, so that I get him again; or the above reward for the delivery of said fellow to me, at Bradshaws Creek, Giles county, Tennessee, with common expenses. Any person taking up said Negro, will direct their letters to Pulaski, Giles county, Tennessee. JOHN HOLCOMB November 4, 1820 http://teacher.scholastic.com/activities/bhistory/undergrou nd_railroad/plantation.htm Click this link for an interactive story about the journey of Walter, a slave in Kentucky. Emancipation: Katie Rowe, Age 88, Tulsa, OK Page 1 of 3 I never forget the day we was set free! That morning we all go to the cotton field early, and then a house [slave] come out from old Mistress on a horse and say she want the overseer to come into town, and he leave and go in. After while the old horn blow up at the overseer’s house, and we all stop and listen, ’cause it the wrong time of day for the horn. We start chopping again, and there go the horn again. The lead row [slave] holler “Hold up!” And we all stop again. “We better go on in. That our horn,” he holler at the head [slave], and the head [slave] think so too, but he say he afraid we catch the devil from the overseer if we quit without him there, and the lead row man say maybe he back from town and blowing the horn himself, so we line up and go in. Katie Rowe Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington Page 2 of 3 When we get to the quarters we see all the old ones and the children up in the overseer’s yard, so we go on up there. The overseer setting on the end of the gallery with a paper in his hand, and when we all come up he say come and stand close to the gallery. Den he call off everybody’s name and see we all there. Setting on the gallery in a hide-bottom chair was a man we never see before. He had on a big broad black hat like the Yankees wore but it didn’t have no yellow string on it like most the Yankees had, and he was in store clothes that wasn’t homespun or jeans, and they was black. His hair was plumb gray and so was his beard, and it come way down here on his chest, but he didn’t look like he was very old, ’cause his face was kind of flashy and healthy looking. I think we all be sold off in a bunch, and I notice some kind of smiling, and I think they sure glad of it. The man say, “You darkies know what day dis is?” He talk kind, and smile. We all don’t know of course, and we just stand there and grin. Pretty soon he ask again and the head man say, No, we don’t know. “Well this the fourth day of June, and this is 1865, and I want you all to ’member the date, ’cause you always going ’member the day. Today you is free, Just like I is, and Mr. Saunders and your Mistress and all us white people,” the man say. 3 of 3 “I come to tell you,” he say, “and I wants to be sure you all understand, ’cause Page you don’t have to get up and go by the horn no more. You is your own bosses now, and you don’t have to have no passes to go and come.” We never did have no passes, no how, but we knowed lots of other [slaves] on other plantations got them. “I want to bless you and hope you always is happy, and tell you got all the right and life that any white people got,” the man say, and den he get on his horse and ride off. We all just watch him go on down the road, and den we go up to Mr. Saunders and ask him what he want us to do. He just grunt and say do like we dam please, he reckon, but get off that place to do it, unless any of us wants to stay and make the crop for half of what we make. None of us know where to go, so we all stay, and he split up the fields and show us which part we got to work in, and we go on like we was, and make the crop and get it in, but there ain’t no more horn after that day. Some the [slaves] lazy and don’t get in the field early, and they get it took away from ’em, but they plead around and get it back and work better the rest of that year. But we all gets fooled on that first go-out! When the crop all in we don’t get half! Old Mistress sick in town, and the overseer was still on the place and he charge us half the crop for the quarters and the mules and tools and grub! Runaway slaves usually hid during the day and travelled at night. Some of those involved notified runaways of their stations by brightly lit candles in a window or by lanterns positioned in the front yard. The resting spots where the runaways could sleep and eat were given the code names "stations" and "depots" which were held by "station masters." There were also those known as "stockholders" who gave money or supplies for assistance. There were the "conductors" who ultimately moved the runaways from station to station. The "conductor" would sometimes act as if he were a slave and enter a plantation. Once a part of a plantation the "conductor" would direct the fugitives to the North. During the night the slaves would move, traveling on about 10-20 miles (15-30 km) per night. They would stop at the so-called "stations" or "depots" during the day and rest. While resting at one station, a message was sent to the next station to let the station master know the runaways were on their way. Sometimes boats or trains would be used for transportation. Money was donated by many people to help buy tickets and even clothing for the fugitives so they would remain unnoticeable. Underground Railroad Code Phrases People who helped slaves find the railroad were "agents" (or "shepherds") Guides were known as "conductors" Hiding places were "stations" "Stationmasters" would hide slaves in their homes Escaped slaves were referred to as "passengers" or "cargo" Slaves would obtain a "ticket" Financiers of the Railroad were known as "stockholders". As well, the big dipper asterism, whose 'bowl' points to the north star, was known as the drinkin' gourd, and immortalized in a contemporary code tune. The Railroad itself was often known as the "Freedom train" or "Gospel train", which headed towards "Heaven" or "the Promised Land" - Canada. “The wind blows from the south today” = warning of slave bounty hunters nearby “A friend of a friend” = a password used to signal the arrival of fugitives with an Underground Railroad conductor “The friend of a friend sent me” = a password used by fugitives traveling alone to indicate they were sent by the Underground Railroad network "Load of Potatoes," "Parcel," "Bundles of Wood," or "Freight" = fugitives to be expected "A friend with friends" = a password used by railroad conductors to signal to the listener that they were in fact a conductor. http://www.freedomcenter.org/underground-railroad/ Click this link for a photograph of an exhibit at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center museum in Cincinnati, Ohio. Florence Lee, Ex-Slave Narrative Sallah White, Ex-Slave Narrative Cleveland Gazette From Slave to President Volume: 09 Issue Number: 07 Page Number: 02 Date: 09/26/1891 Cleveland Gazette Children of Slaves Deemed Illegitimate Volume: 05 Issue Number: 39 Page Number: 02 Date: 05/12/1888 Palladium Of Liberty Form of a Petition Volume: 01 Issue Number: 01 Page Number: 03 Date: 12/27/1843