Entering the Conversation PowerPoint

advertisement

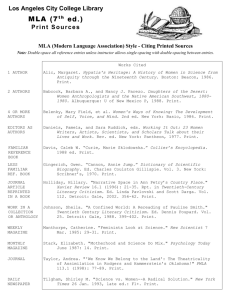

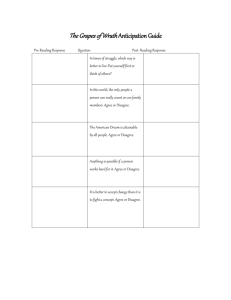

Entering the Conversation English 101 September 22, 2008 To succeed with Paper #2, understand… • How to introduce what others are saying • How to summarize what others are saying • How to quote (and cite) what others are saying • How to respond to what others are saying • How to signal the differences between what you are saying and what others are saying Surprise! • All of the items on that list are in chapters 1 through 5 of They Say/I Say • However… ▫ You are also responsible for knowing how to use parenthetical citations and how to create a proper works cited list. See Maimon, A Writer’s Resource or another such handbook. Entering the Conversation • When we say “entering the conversation,” we mean that when you are responding to a text you must put it in context and interact with it as you make your point(s). ▫ A REPORT simply restates what has been said. ▫ An ANALYSIS shows that you can break things apart and show how they fit together as a whole. ▫ A “conversation” requires both report and analysis but also your own assertions (the ARGUMENT). Structuring the Conversation • Provide context for your claim. • Present your claim. • Support your claim, which includes (but is not limited to): ▫ Summarizing, framing, clarifying, pointing out flaws in, and amending “their” claims ▫ Remember to always keep what “they say” in view. • Wrap it up. “They Say” – Context for Your Own Claim • Common sense dictates that _____. ▫ Explain, then make your own claim • I’ve always believed that ________. ▫ Explain, then make your own claim. • Although not stated directly, A appears to believe _________. ▫ Explain, then make your own claim. The Art of Summarizing Concise Accurate Brief Independent Neutral The Art of Summarizing (cont’d) • Understand what you are summarizing. • Avoid LIST SUMMARIES. • Use signal verbs. ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ argue, assert, believe, claim, etc. acknowledge, agree, endorse, support, etc. complain, contend, question, refute, etc. demand, encourage, implore, urge, etc. Citing a Summary • When you are summarizing a text, you still have to cite the page numbers you are summarizing, if you are summarizing only part of the text. ▫ Smilansky discusses gossips and terrorists to make a point about the contradictions inherent in moral complaints (92-93). Smilansky, Saul. “The Paradox of Moral Complaint.” 10 Moral Paradoxes. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007. 90-99. Print. Parenthetical References • Parenthetical references should point the user directly to the citation at the end. ▫ (Author Last Name Page #) -> (Smith 25) ▫ There should be an entry in the works cited for Smith’s text. • However, if the author is already stated, the reference looks different: ▫ According to John Smith, we are “doomed” (51). Parenthetical References • The reference always appears at the end of the sentence in which the quotation or paraphrasing is located. • The period goes after the parenthesis. • There is no page number used for parenthetical references of web sites. Works Cited • ALWAYS refer to a handbook or a legitimate web site before creating your works cited page(s). • All references in your text should match up with a citation in the works cited list. • Entries are arranged alphabetically by the author's last name, or by the title of the work if there is no author • Indent entries that break across lines. • Entries are double-spaced The Art of Quoting • Write the arguments of others into your own text…literally. ▫ Provides credibility to your own argument ▫ Ensures your argument is fair and accurate ▫ Quotations act as evidence • BE WARY! Do not ▫ quote too little ▫ quote too much Quoting is More than Putting Words in Quotation Marks • Quote relevant passages—but only quote what you need • Frame every quotation; avoid “hit and run” quotations • Use the QUOTATION SANDWICH ▫ Introduction ▫ Quotation ▫ Explanation The Quotation Sandwich According to Smilansky, “a person cannot complain when others treat him or her in ways similar to those in which the complainer freely treats others” (91). In other words, Smilansky believes that if Bob kills my family, Bob doesn’t have the right to complain if I kill his. This situation exemplifies the paradox of moral complaint. Smilansky, Saul. “The Paradox of Moral Complaint.” 10 Moral Paradoxes. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007. 90-99. Print. Three Ways to Respond • Agree, disagree, or some combination of agreement and disagreement. ▫ The point is that you RESPOND AT ALL. • Declare your stance quickly and clearly. • Responding well takes practice; it is more difficult than it seems. Disagree…and Explain Why • Disliking something is not the same as disagreeing with it. • If you disagree with something you must fully explain why that is the case—with a logical argument. • Disagreeing is MORE than simply adding “not” to what someone else said. Disagree…and Explain Why • I think X is mistaken because she overlooks an entire field of research which I will now summarize for you. • I disagree with X’s view that grass is blue because, as recent research has shown, grass is only ever blue in Kentucky and we are in Washington. Agree…But With a Difference • Avoid parroting back what someone else has said. • I agree that coffee in the morning is a good thing, because my experience as a coffee drinker confirms it. • Smilansky’s theory of the paradox of moral complaint is useful as it sheds light on the problems of guilt and innocence. Agree and Disagree Simultaneously • Move beyond the “is too/is not” exchanges and the potential for shouting matches. • Complicate your argument and provide nuance so as to highlight your skills. • It does not have to be a 50/50 proposition. Agree and Disagree Simultaneously • Although I agree with Jones up to a point, I cannot accept her overall premise that grass is always blue. ▫ Sometimes grass is blue ▫ Most of the time grass is green ▫ Grass can be other colors ▫ There is plenty of evidence to work through and another conclusion to be made. Distinguishing What YOU Say From What THEY Say • Who says what should always be clear. ▫ Use VOICE MARKERS • When you read texts, pay close attention to voice markers in use. Distinguishing What YOU Say From What THEY Say X argues ______. According to X, ______. The evidence shows that ______. It is widely held that ______. I wholeheartedly endorse what X calls the ___________. • The conclusions regarding ________, which X refers to as _______, add weight to the argument that _________. • • • • • Effective Uses of “I” • Assertiveness // Clarity // Positioning Original: “In studying American popular culture of the 1980s, the question of to what degree materialism was a major characteristic of the cultural milieu was explored.” Better: “In my study of American popular culture of the 1980s, I explored the degree to which materialism characterized the cultural milieu.” Ineffective Uses of “I” • When it’s already clear it’s your statement, or you have already asserted your position Original: “I think that Aristotle's ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases, or at least it seems that way to me.” Better: “Aristotle's ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases.” Style, aka “your voice” • • • • Say what you mean Say it clearly Say it an appropriate tone Be yourself BUT… AVOID WORDINESS • Common reasons for wordiness ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ Uncertainty about your topic Lack of a developed argument Lack of evidence Uncontrollable urge to use adjectives for everything. Common Wordiness Problems • Lots of qualifiers ▫ WORDY: Most people usually think that many puppies are generally pretty cute. ▫ CLEAR: Most people think that puppies are cute. • Using words that mean the same thing ▫ WORDY: Adrienne fulfilled all our hopes and dreams when she saved the whole entire planet. ▫ CLEAR: Adrienne fulfilled all our hopes when she saved the planet. Common Wordiness Problems • Overuse of prepositional phrases ▫ WORDY: The reason for the failure of the economic system of the island was the inability of Gilligan in finding adequate resources without incurring expenses at the hands of the headhunters on the other side of the island. ▫ CLEAR: Gilligan hurt the economic system of the island because he couldn't find adequate resources without angering the headhunters. Common Wordiness Problems • Using stock phrases you can replace with one or two words ▫ WORDY: The fact that I did not like the aliens affected our working relationship. The aliens must be addressed in a professional manner. ▫ CLEAR: My dislike of the aliens affected our working relationship. The aliens must be addressed professionally. Ostentatious Erudition “Never use a long word where a short one will do.” – George Orwell • Do not blindly use multi-syllabic words in an effort to sound “more collegiate.” ▫ Can make you sound like you don't know what you are talking about ▫ Can give the impression that you are plagiarizing from a source you don't understand Ostentatious Erudition • Never use a word you can't clearly define. ▫ If you know one, and can use it correctly, and it fits with your tone, then great. BAD: "That miscreant has a superlative aesthetic sense, but he's dopey.“ • It’s okay to repeat the same word(s) in your paper, particularly when they are significant or central terms. ▫ Don’t try to fix something that isn’t broken. Ostentatious Erudition • Something nice, from Ecclesiastes: “I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.” Ostentatious Erudition • What happened when some overzealous student got hold of that passage: “Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.” Arguing is Not Just Talking Loudly • You cannot produce a scholarly argument simply by using exclamation points and calling people names. • Instead ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ Make a claim. Provide evidence. Acknowledge or make a counterargument. Have an awareness of your audience. Cite your source. Avoid Fallacies! • • • • • • • Hasty generalization Missing the point Post hoc ergo propter hoc Appeal to false authority Ad populum Ad hominum Appeal to ignorance • Trust me, there are more…