southamindependence lesson plan

advertisement

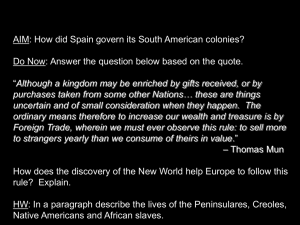

Rebellion in Spanish America – Context Setting In the 1500s, Europeans began to conquer native civilizations in the Americas, claiming territories in the Americas for European nations. Soon after conquering the native peoples, the Europeans established colonies (settlements) in the Americas. South America was colonized mostly by the Spanish, who brought great changes to northern, southern, and western South America. The social and cultural changes in South America were enormous. The mixing of peoples – Native Americans, Europeans, and the African slaves brought by the Europeans – resulted in the creation of new ethnic groups (mestizaje). A clear social hierarchy (ranking of peoples) developed, with the pure-blooded Spaniards at the top and the African slaves at the bottom. The Spaniards introduced new forms of culture to the people of the Americas, exposing them to Spanish art, architecture, and customs. The dominant religion in Spain was Catholicism, and the Spanish settlers included Catholic missionaries who brought, and sometimes forced, Catholicism on Native Americans and African slaves. The economic and political changes brought by the Spanish created much resentment (hatred) within the colonies. The Spanish set up colonial governments run by Spaniards. Native Americans, blacks, and American-born people of Spanish descent were not allowed to have significant roles in the government, yet were expected to follow the laws set up by the Spanish. The inhabitants of the colonies, no matter their ethnic or racial background, were expected to help expand the colonies’ economy and pay taxes to Spain. The Spanish set up trade restrictions that favored Spanish businesses and the Spanish government. All trade had to be conducted through Spain; in other words, the colonies could not trade directly with each other or with other countries. In addition, colonists were not allowed to open factories that would compete with those in Spain. The combination of resentment towards Spanish rule and the spread of Enlightenment ideas – including selfgovernment and the protection of individual rights – eventually pushed the people of South America to fight for independence from Spain. By 1830, all of Spanish-America had won its independence from Spain and more inclusive and democratic governments were established. SOCIAL HIERARCHY IN THE SPANISH AMERICAS 1) Peninsulares—those born in Spain. Peninsulares were wealthy (rich) and well-educated. They controlled the Spanish colonies’ economy and government as well as the Catholic Church in the colonies. 2) Creoles—pureblooded Spaniards, born in the colonies. Creoles were also wealthy and welleducated. Legally (according to law), creoles had the same standing as the peninsulares, but were overlooked by the leaders of Spain when choices were made about who would hold important jobs in the colonial government and Catholic Church in the colonies. The Spanish settlers in America, known as peninsulares, were at the top of a very rigid (unchanging) social hierarchy. While the pensinsulares made up less than one percent of the population, they were in charge of the government, the economy, and the Catholic Church in the colonies. The colonial social hierarchy was in place very early on, as can be seen in the writings of José de Acosta, a Spanish priest who commented in 1585 on castas, or social classes, in Peru: Throughout this realm [territory] there are many blacks, mulattos, mestizos, and many other mixtures of people, and every day their number increases…Those [Spaniards] who reflect [think] on this matter with care fear that in time the number of these [castas] ill become much larger than that of the children of Spaniards born here (who are called creoles)…and that therefore they will be able to raise as a city in revolt… In fact, the creoles were the driving force behind the majority of revolts and revolutions that took place in the Spanish colonies in the 1800s. While other groups of people resented (hated) Spanish rule, the creoles’ resentment of the fact that they were second-class citizens pushed them to rebel. 3) Mestizos—people of mixed Native American and Spanish descent. As time wore on, mestizos became the largest percentage of the population in the Spanish colonies. Most mestizos were farmers, artisans, or shop owners. Other mestizos held management positions in mines or on plantations. 4) Mulattos— people of mixed European and African descent. Most mulattos worked as servants or in small businesses. 5) Native Americans—descendants of those people who had been living in South America before the arrival of the Spanish. While some Native Americans worked for peninsulares and creoles, others were independent farmers. Although many Native Americans continued to speak their own languages and practice their own traditions, most became Catholics. 6) Free blacks—this category included former African slaves (or slaves of African descent) and their children. Some free blacks bought their freedom, while others were freed by their former owners. Most free blacks worked on farms or as laborers. 7) Slaves—African slaves or slaves of African descent. Slaves in the Spanish colonies did have some rights, including the right to marry and the right to own property. Slaves could also buy their freedom. Most slaves became Catholics. Bolivar and San Martín People all over the South American continent were influenced by the beliefs and actions of key revolutionary heroes, including Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín. Simón Bolívar, also known as “The Liberator,” played an important role in helping much of northern South America gain its independence from Spain. Bolívar, a wealthy Venezuelan creole, was greatly influenced by European ideas about democracy. When Bolívar was a young boy, his tutor exposed him to the ideas of the Enlightenment – including self-government and individual rights – and Bolívar furthered his knowledge of Enlightenment ideas during his travels to Europe in the early 1800s. Bolívar believed that the Spanish peninsulares must be overthrown, but that the people of South America, having had no practice in democracy, were not yet ready to take on complete self-government. Bolívar had seen the first independent government of Venezuela (which had been set up so that local governments would share power with the central government) taken down by the Spanish in 1812, and believed that only a strong, central government would succeed. Bolívar’s dream, which never became a reality, was to unite all of South America into one free nation. He did succeed in liberating much of the continent from Spain and in uniting much of northern South America as the new nation of Gran Colombia. Another key revolutionary leader was José de San Martín, a wealthy Argentinean creole. San Martín helped to liberate Argentina from Spain and then moved to join the Chilean revolutionary hero, Bernardo O’Higgins, to liberate Chile. San Martín continued to move his fight northward and contributed to Bolívar’s fight in Ecuador and Peru. Continuing Issues Unfortunately, most of the new South American governments struggled to develop well organized, just, and prosperous societies. While the nations were new, the problems they faced were not. The old social hierarchy remained in place, with the creoles instead of the peninsulares at the top. The new nations, having developed no industry of their own under Spanish rule, were still economically dependent on Spain and other European countries for manufactured goods. Many of the new governments borrowed heavily from wealthier nations in order to develop industry, only to be burdened with problems created by debt. In February of 1819, Simón Bolívar helped to found the new nation of Gran Colombia (which included present day Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, and Panama). Bolivar spoke to the new Congress of Angostura, which had before it the task of creating a constitution for the new nation. In his speech, known as the Angostura Address, Bolívar outlined some of his thinking about democracy: The Angostura Address, February 15, 1819: …The continuation of authority [power] in a single individual has frequently been the downfall of democratic governments. Repeated elections are essential in popular systems, because nothing is more dangerous than allowing the same citizen to remain in power over a long period of time... The most perfect system of government is that which produces the greatest possible amount of happiness, social security and political stability…Venezuela’s government is a republican [elected] one, as it has been and must be; its foundation should be the sovereignty [freedom] of the people: the division of powers, civil liberty [individual freedom], the abolition [end] of slavery, monarchy and privilege. We must have equality in order to reshape, so to speak, the human species, with its political opinions and public customs, into one single whole… The system of government Bolívar proposed included a centralized government with four branches: The Congress of Angostura considered Bolívar’s recommendations but rejected the Areopagus and changed the hereditary Senate to one in which Senators served life terms. The right to vote was given to educated and wealthy male citizens who were known as “active citizens.” Less educated and less wealthy men, or “passive citizens,” were not given the right to vote. Assessment Questions: 1. Who was the creole “Libertador” from Argentina? From Chile? 2. Although Bolívar favored democracy, he favored centralized governments (which tends to give less autonomy to local regions and peoples). Why? 3. What major problems did newly independent nations in Latin America face? 4. Do you agree with Bolívar’s statements in the excerpt from his “Angostura Address?” Which Enlightenment philosophers’ ideas do you see reflected in his quote? 5. What is your view of the type of government Bolívar proposed? Does it seem to match with his statements? How so, and how not?