America's History Seventh Edition

advertisement

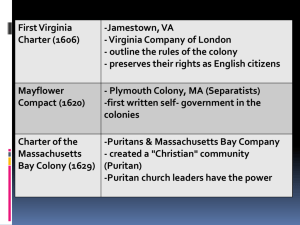

James A. Henretta Eric Hinderaker Rebecca Edwards Robert O. Self America’s History Eighth Edition America: A Concise History Sixth Edition CHAPTER 2 American Experiments 1521‒1700 Copyright © 2014 by Bedford/St. Martin’s II. Plantation Colonies A. Brazil’s Sugar Plantations • By 1590, Portuguese colonists transformed coastal Brazil into a sugar plantation zone; plantations included both sugar cultivation and milling, extracting, and refining operations. • The diminished Indian population’s inability to provide sufficient labor led colonists to import growing numbers of African slaves; • by 1620, Brazil was a sugar colony based on a slave labor system. II. Plantation Colonies B. England’s Tobacco Colonies 1. The Jamestown Settlement • In 1606, a charter was granted to the Virginia Company for land from present-day North Carolina to southern New York; primary goal was trade with native people. • In 1607 traders (all men) sent for economic venture; settlement failed horribly; only 38 of 120 men were alive after nine months; many destroyed by disease, warfare, and famine. • Powhatan (Algonquin) forged relations with later settlers, marrying his daughter Pocahontas to John Rolfe; Rolfe produced tobacco in the region; production of tobacco and availability of land grants encouraged migration to the region. • In 1619, House of Burgesses convened to make laws and levy taxes. • The Indian War of 1622 – Powhatan’s brother Opechancanough [O-pee-chan-KA-no] led an unsuccessful uprising in 1607; captured John Smith; later became chief and vowed another uprising; 1622 revolt killed 347 English settlers; • King James revoked the charter and made Virginia a royal colony in 1624; settlers now followed English rule: appointed governor, elected assembly, formal legal system, and the Anglican Church. • 3. Lord Baltimore Settles Catholics in Maryland – A second tobacco-growing colony was created by King Charles’s granting of land to Lord Baltimore (Cecilius Calvert); became a refuge for Catholics; population grew quickly; 1649 Toleration Act granted all Christians in the colony the right to religious freedom. II. Plantation Colonies C. The Caribbean Islands 1. European colonization – In 1624, English and French colonists occupied St. Christopher (St. Kitts) in the Caribbean; by 1655, French also occupied Martinique, Guadeloupe and St. Bart’s; English occupied Nevis, Antigua, Montserrat, Anguilla, Tortola, Barbados, and Jamaica; Dutch occupied St. Eustatius. II. Plantation Colonies C. The Caribbean Islands 2. Plantation economy – England, France, and Holland established plantation economies in the region and, after experimentation with tobacco, indigo, cotton, cacao and ginger, many planters shifted focus to sugar cultivation wherever possible. 1. Who are the people depicted in this image? What are they doing? 2. What does this image suggest about the process of sugar refining and the people who controlled it? 3. What does the image suggest about the people who actually worked on sugar plantations? II. Plantation Colonies D. Plantation Life Indentured Servitude – By 1700, more than 100,000 English migrants had come to Chesapeake as indentured servants; • many were men seeking land and opportunity who could not afford passage; some were women; • all were valuable but severely exploited; • many died before their indenture had ended; • those who survived rarely received what had been promised. II. Plantation Colonies D. Plantation Life African Laborers – In 1619, John Rolfe noted first Africans sold in the Chesapeake; • at first these men were not legally enslaved; by 1660s status was changing; • value of tobacco declined and landowners desired ways to make a profit despite declining prices; African labor was “cheaper” than white labor, they concluded; • residents of the Chesapeake became increasingly race conscious, referring to color (white-black). III. Neo-European Colonies A. New France • Fur trade – In the 1530s, Jacques Cartier ventured up the St. Lawrence River and claimed it for France; • in 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded the furtrading post of Quebec; • the French traded manufactured goods and guns to Native Americans in the region for beaver pelts and other furs which were popular in Europe. III. Neo-European Colonies A. New France • The Jesuit missions – From 1625–1763, hundreds of French Jesuit priests lived among the Indian peoples and came to understand and respect them; • conversion failed when Indians did not see results from the use of Christian prayers. III. Neo-European Colonies A. New France • Life in New France – In 1662, King Louis XIV made New France a royal colony, but migration and farming languished; New France’s population remained small. • France eventually claimed a vast quantity of land from St. Lawrence Valley through the Great Lakes and down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers; • by 1718, Robert de La Salle had founded the port of New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi. III. Neo-European Colonies B. New Netherland Hudson River settlement – In 1609 with Dutch support, Englishman Henry Hudson located a wealth of fur along a river in present-day New York; • in 1621, Dutch founded the colony of New Netherland, sending farmers and artisans to the region to build a community; the new colony failed; • the small population of Holland meant few migrants would go to North America; • West India Company granted land to wealthy Dutch along the Hudson who were unsuccessful in populating the estates. III. Neo-European Colonies B. New Netherland England invaded • Settlers had hostile relations with Algonquin neighbors; formed an uneasy alliance with Mohawks. • Dutch focused on business profits and not land acquisition. • New Netherland had a diverse population of Dutch, English, and Swedish; • England invaded and took control of the colony in 1664; leadership was uncertain in the years that followed, as Dutch culture remained but political control was contested; • in 1699, a colonist observed region was “like a conquered Foreign Province.” III. Neo-European Colonies C. The Rise of the Iroquois Iroquois domination • The Five Nations of the Iroquois bartered with French and Dutch traders for European guns; • Iroquois grew their population quickly and became powerful with the use of European weapons; aggressively attacked other groups, ritually killing the men and capturing women and children. • In the 1660s, New France committed to all-out war against the Iroquois; in 1667, the Five Nations in New France admitted defeat, accepted Jesuit missionaries into their communities, and settled in St. Lawrence Valley. III. Neo-European Colonies C. The Rise of the Iroquois Alliance with English settlers • Iroquois in NY survived war with France and forged new alliance with Englishmen who had taken control of New Netherland; • they remained a dominant force in politics of the Northeast for generations to come. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England The Pilgrims • Religious separatists who left the Church of England; lived briefly among Dutch Calvinists in Holland; 35 then migrated to America along with 67 who left England; led by William Bradford aboard the Mayflower; • first winter extremely harsh, only half survived until spring; built a community of houses and planted crops; • by 1640, Plymouth had 3,000 settlers because of worsening religious tensions in England. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England John Winthrop and Massachusetts Bay • In 1630, Winthrop led 900 Puritans to America and became the first governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony; • wanted to create an ideal “City upon a Hill”; • joint-stock corporation was transformed into a representative government with council and assembly, ruled by “the godly”; • Puritans limited voting rights to those who were members of the church; unlike Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts Bay established Puritanism as the statesupported religion. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England Roger Williams and Rhode Island • Massachusetts Bay was purged of all dissenters; • Williams was a Puritan minister in Salem who opposed establishing Congregationalism as official religion of the colony and advocated tolerance; he also questioned the practice of taking Indian land; • was banished in 1636; established Providence on land purchased from Narragansett Indians. • In 1644, a new colony was established, Rhode Island, with no legally established church and religious tolerance. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England Anne Hutchinson • Wife and mother of seven; held weekly prayer meetings for women and made accusations against Boston ministers; • believed in a “covenant of grace” not “works”; • declared that God “revealed” divine truth to individuals and not only through ministers. • Puritan belief that women were inferior to men hastened officials’ anger towards Hutchinson; she was banished in 1637; settled in Rhode Island. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England (cont.) 5. The Puritan Revolution in England – Religious war broke out in England; English Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians demanded religious reform and parliamentary power; after years of civil war, Oliver Cromwell emerged victorious. In 1649, a republican Commonwealth was declared; elaborate rituals and bishops were banned from the Church of England. The crown was restored in 1660 after Cromwell’s death; restoration of the monarchy dashed Puritans’ hopes to return to England; the Puritan colonies now stood stand as outposts of Calvinism and the Atlantic republican tradition. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England (cont.) 6. Puritanism and Witchcraft – Puritans saw signs of God and Satan in the physical world (birth defects, storms, unusual events, etc.). Many Christians incorporated some pagan practices into their daily lives; condemned those who claimed powers as healers or prophets. Between 1647 and 1662, fourteen New Englanders were hanged for witchcraft. The 1692 episode in Salem was America’s most dramatic episode of witch-hunting; after young girls claimed to experience seizures and accused neighbors of bewitching them, accusations spun out of control. Massachusetts Bay tried 175 people for witchcraft and executed 19 of them. Debate continues among historians as to whether the witchcraft hysteria was the result of class differences or efforts to control/limit the activities of women in the colonies. Charges of witchcraft were significantly reduced as colonists began to adopt the philosophies of the European Enlightenment, including rational and scientific thought. III. Neo-European Colonies D. New England (cont.) A Yeoman Society, 1630–1700 • Proprietors received tracts of land from the general courts of the colonies of Massachusetts and Connecticut and then distributed the land to male heads of household; all families received some land; • most adult men could vote in town meeting (local government); largest plots of land went to men of high social status; • the possibility of land ownership made New England a place of great opportunity for men. IV. Instability, War, and Rebellion A. New England’s Indian Wars Puritan-Pequot War • In 1637, a combined force of Massachusetts and Connecticut militiamen, accompanied by Narragansett and Mohegan warriors, attacked a Pequot village and massacred five hundred men, women, and children; • acting on the belief that their presence was divinely ordained, Puritans drove surviving Pequots into oblivion and divided their lands; • only rarely did Puritans make effort to convert Indians to Puritan religion. IV. Instability, War, and Rebellion A. New England’s Indian Wars Metacom’s War, 1675–1676 • The Wampanoag leader Metacom (known to English as King Philip) wanted to expel Europeans; forged an alliance with the Narragansetts and Nipmucks to attack settlements in New England; • Indians destroyed one-fifth of the English towns in Massachusetts and Rhode Island; nearly 5 percent of the adult population in New England was killed; • approximately 4,500 Indians died and more were displaced from land; • Metacom was killed by Mohegan and Mohawk warriors hired by Massachusetts Bay leaders. IV. Instability, War, and Rebellion B. Bacon’s Rebellion Frontier War • Poor freeholders and former indentured servants in the Chesapeake wanted lands occupied by Native Americans in Virginia; • in 1675, fighting broke out when vigilante Virginia militiamen murdered thirty Indians; • intensified when group defied Governor Berkeley’s orders and killed five Susquehannock leaders; Susquehannocks retaliated by killing three hundred whites. • Settlers dismissed Berkeley’s proposed defensive strategy as a plot to impose high taxes on the poor. IV. Instability, War, and Rebellion B. Bacon’s Rebellion Challenging the Government • Nathaniel Bacon, an English migrant with a position on the governor’s council, emerged as leader of Virginia rebels; disagreed with Berkeley on frontier policy; demanded a military commission but was denied; organized a militia to attack Indians on the frontier. • Political struggle began between Bacon and the governor; Bacon issued “Manifesto and Declaration of the People,” calling for death or removal of Indians and an end to rule by wealthy “parasites” in Virginia. • Bacon’s army burned Jamestown and plundered the plantations of wealthy. Bacon died suddenly in October 1676 of dysentery; 23 of his followers were hanged. • Wealthy leaders in Virginia realized that they had to appease the poor and landless: cut taxes, expelled Indians from the frontier, • increased importation of slaves while decreasing use of indentured servants. In 1705, House of Burgesses legalized chattel slavery.