The Bishop Orders his Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church Rome, 15

advertisement

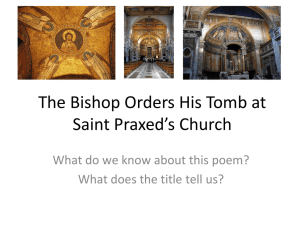

The Bishop Orders his Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church Rome, 15-- Notes 1] First published in Hood's Magazine, March 1845, and reprinted in Dramatic Romances and Lyrics, 1845. St. Praxed's (Santa Prassede is the Italian form) is an actual church in Rome; the bishop is, of course, fictitious. 21] epistle-side: the side from which the epistles are read, theright-hand side as one faces the altar. 31] onion-stone: translation of the Italian name--cipollino--for a marble that breaks into layers. 42] lapis lazuli: a blue stone of which there is a fine specimen, supposed to be the largest in existence (see lines 48-9 below), in Il Gesu Church in Rome. 46] Frascati: a summer resort some dozen miles from Rome on the slope of the Alban hills. 54] antique-black: It. nero antico, black marble. 56] Such ornamentation is common on the ancient sarcophagi. The thyrsus is the cone-tipped staff, carried by followers of Dionysus. 66] travertine: 74] The the common limestone of Rome. collecting of Greek MSS. was a favourite pursuit of the virtuosi. 79] Ulpian was a late juristic writer (d. 228 A.D.); the Latin he used, therefore, differed from that of Tully (Cicero), which was accepted as the standard language of scholarship. 87] crook: the pastoral staff, symbol of his office. 95] Browning himself explained that the blunder in sex was due to the condition of the dying man; "he would not reveal himself as he does but for that." St. Praxedes was a woman. 99] Cicero 108] vizor: would have used elucebat; the inchoative form marks later Latin. mask, such as was worn by actors on the ancient stage. Term: a square pillar ending in a bust, like those of the god Terminus. The Pursuit of Wealth in "The Bishop Orders his Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church" and Great Expectations Rhianna Shaw '11, English 600J, Brown University, 2010 [Home —> Authors —> Robert Browning —> Charles Dickens —> "The Bishop Orders His Tomb"] Although the genres, settings, characters, and imagery of “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s” and Great Expectations differ greatly, Dickens” and Browning’s use of the first-person narrative serves to draw the reader in whilst establishing a multifaceted view of their protagonist. Both examine the pursuit of material wealth and the unpleasant effects it has on purportedly upstanding figures. In a time when the economic climate was changing, they challenge the notion of money and what possessing it entailed. Money (or some equivalent) always has driven, and always will drive society worldwide. It is therefore hardly surprising then that it has been thoroughly examined in centuries of literature. However, with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution money, or more specifically, those who possessed it, were beginning to assume a whole new identity. One of the most iconic novels of the Victorian Era, Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations follows the journey of a young boy’s pursuit of wealth, and the trials and tribulations entailed in obtaining it and everything it signified. Telling the tale of an ailing Bishop’s dying wish for an extravagant resting place, “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s” by Robert Browning is another of the great works of the century that examines the desire for riches. With the onset of the Industrial Revolution Britain was undergoing an extreme economic upheaval, the effects of which were far-reaching, particularly in the class system. Money, heretofore only associated with but not a criterion for admittance into the upper class, was beginning to become a mark of social standing. The daughters of prosperous merchants, for example, were becoming perfectly acceptable matches for certain members the (usually financially challenged) aristocracy. The importance of bloodlines was becoming adumbrated by material wealth. Dickens’s Miss Havisham is the embodiment of this social phenomenon: born the daughter of an extremely wealthy brewer she is considered, especially by Pip, upper class, and as an extension of this so is Estella. It is because of this Pip so desperately wants to become a gentleman, and for this he needs only money and education, not a superior heritage. The importance of money and its significance to Pip is highlighted when his wildest dreams are finally realised: “Bear in mind then, that Brag is a good dog, but Holdfast is a better. Bear going to make my that in mind, will you?” repeated Mr. Jaggers, shutting his eyes and nodding his head at Joe, as if he were forgiving him something. “Now, I return to this young fellow. And the communication I have got to make is, that he has great expectations.” Joe and I gasped, and looked at one another. “I am instructed to communicate to him,” said Mr. Jaggers, throwing his finger at me sideways, "that he will come into a handsome property. Further, that it is the desire of the present possessor of that property, that he be immediately removed from his present sphere of life and from this place, and be brought up as a gentleman — in a word, as a young fellow of great expectations." My dream was out; my wild fancy was surpassed by sober reality; Miss Havisham was going to make my fortune on a grand scale. “The Bishop Orders His Tomb” also largely concerns the hypocrisy of monetary pursuit. Although the poem's bishop is fictional, Saint Praxed’s Church very much exists. Situated in Rome, it is dedicated to a martyred virgin of the second century who rejected paganism for Christianity and donated her wealth to the Church. It is no accident that Browning chose it to satirize the hypocrisy of the Renaissance Church. John Ruskin remarked upon this in Modern Painters IV, where he praised the poet's accurate depiction of its worldliness, inconsistency, pride, hypocrisy, ignorance of itself, love of art, of luxury, and of good Latin. It is nearly all I said of the central Renaissance in thirty pages of The Stones of Venice [1851-3] put into as many lines, Browning's being the antecedent work. [Works, xx, 34] Here is a bishop, listing all the precious items he has collected for the sole purpose of leaving behind an impressive tomb, concerned more by his desire to beat his old adversary, Gandolf, than by following the example of this patron saint and abstaining from all material wealth: And I shall fill my slab of basalt there, And 'neath my tabernacle take my rest, With those nine columns round me, two and two, The odd one at my feet where Anselm stands: Peach-blossom marble all, the rare, the ripe As fresh-poured red wine of a mighty pulse. Ñ Old Gandolf with his paltry onion-stone, Put me where I may look at him! True peach, Rosy and flawless: how I earned the prize! Browning mocks the Bishop’s notion of death, as the he even practices the position he will lie in within his tomb: Dying in state and by such slow degrees, I fold my arms as if they clasped a crook, And stretch my feet forth straight as stone can point, And let the bedclothes, for a mortcloth, drop Into great laps and folds of sculptor's-work: In this poem Browning deviates from his customary formatting, using iambic pentameter unrhymed lines as opposed to the rhyming schemes found in poems of his such as “My Last Duchess” and “Soliloquy of a Spanish Cloister.” By using blank verse he is not only emphasising the single-mindedness of the Bishop’s last moments but is also creating a sense of informality not found in his other poetry. This style is more personal and in keeping with the first person narrative. This is not unlike the close narration of Pip in Great Expectations. However, despite their use of first-person narrative both Browning and Dickens successfully convey the more objectionable sides to their protagonists: the Bishop’s greed and Pip’s snobbery. Sources Allingham, Philip V. "Robert Browning's "The Bishop Orders His Tomb" (1845): Another Renaissance Portrait Ñ The Sensual, The Profane, and the Sacerdotal." The Victorian Web. Web. 17 May 2010. Collins. "Browning's "The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed's. Rome. 15-"" The Victorian Web. Web. 17 May 2010. Monteiro, George. “The Apostasy and Death of St. Praxed's Bishop.” Victorian Poetry 8 (1970). Robert Browning's "The Bishop Orders His Tomb" (1845): Another Renaissance Portrait — The Sensual, The Profane, and the Sacerdotal Philip V. Allingham, Contributing Editor, Victorian Editor; Faculty of Education, Lakehead University (Ontario) [Home —> Authors —> Robert Browning —> Works —> Genre and Style —> Dramatic Monologue—> "The Bishop Orders His Tomb"] Note: Robert Browning first visited the Basilica of Santa Prassede, near Rome's Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, in October 1844, and sent this poem to Hood's Magazine (London) on 18 February 1845, although the accompanying cover letter implies an earlier date of composition. Much of the poem's irony lies in the fact that "St. Praxed" (as Browning has anglicized her name) was a virgin saint of the second century who gave her wealth to the poor and to the Church. The pagan, Christian, materialistic, and artistic elements of the Renaissance spirit, its essential "neoclassicism," which lie behind "My Last Duchess" are again evoked in this poem, as John Ruskin remarked in Modern Painters IV: Its worldliness, inconsistency, pride, hypocrisy, ignorance of itself, love of art, of luxury, and of good Latin. It is nearly all I said of the central Renaissance in thirty pages of The Stones of Venice [1851-3] put into as many lines, Browning's being the antecedent work. [Works, xx, 34] Rhetorically, these are the Bishop's last words, only some of which are addressed to his sons, who depart as the poem concludes. Bargaining (about the quality of the stone and position for the tomb) and confession (about the hidden lapis) are formulaic of a deathbed speech. The opening line suggests the ornamental trapping of a sermon, but the Bishop's life has been at total variance with the spirit of that quotation from "Ecclesiastes." His bargaining point for the tomb is that, having Saint Praxed's ear, he will be able to intercede to see that his sons get what all young men in the Renaissance most wanted: fast horses, beautiful mistresses, and Greek manuscripts. Sensuality, paganism, and Christianity are inextricably connected in the Bishop's mind, for he is characteristic of the clergy of his age. And yet the Bishop is more human and sympathetic than that other representative figure, the Duke in "My Last Duchess," because of his love for the boys' mother and his jealousy of Gandolf, a rivalry he intends to pursue throughout eternity. Unlike people in the Middle Ages, his concept of Heaven is earthand pleasure-bound. Furthermore, this poem possesses a marked vein of humour lacking in "My Last Duchess." The Bishop's programme for his tomb is typical of Renaissance artistic taste (similar to Julius II's for his projected tomb, and Sigismundo Malatesta's for his Tempio in Rimini). The speaker uses Ciceronian syntax, making his sentences richly complex and ornately artificial. Like the Duke, he is a connoisseur, but a genial one in love with life, and ready to bless his sons, even though he suspects that they do not intend to honour his request about the tomb, which represents the Renaissance ideal of undying fame. Reference Pettigrew, John, ed. Robert Browning The Poems. Vol. 1. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 1981. Robert Browning's Use of Biblical Typology in "The Bishop Orders His Tomb" George P. Landow, Professor of English and Art History, Brown University [Home —> Authors —> Religion —> Typological Interpretation of the Bible] [Adapted from Victorian Types, Victorian Shadows: Biblical Typology in Victorian Literature, Art, and Thought, 1980. Full text] The almost inevitable disparities between type and fulfillment in the life of a fictional character, like a character's misapplication or misinterpretation of such symbolism, produces a range of ironic commentary on fictional personages. Since the time the Wife of Bath argued for female superiority with wonderfully twisted allusions to scripture, English authors have long employed such subjective distortions of interpretive procedures as a means of creating and occasionally satirizing figures in their own works. As Barton demonstrates, such uses of commonplace types can produce gentle, if far-reaching, satire. They can also induce the reader to make far harsher judgments of a fictional character, and Rochester's misapplication and misreading of Achan's tent exemplifies such an earnest condemnation. The double perspective or context provided by typology makes it particularly useful to the writer of dramatic monologues, since the disparity between literal and symbolical (or type and antitype) provides him with an effective means of allowing his character to convey more than he intends. Robert Browning, who is the great typologist among Victorian poets, frequently employs types for this purpose. For instance, "The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church. Rome, 15 -- " (1845) uses a number of types to emphasize the precise nature of the prelate's characterizing attitudes towards life and death, matter and spirit. The Bishop, whom Ruskin took to be a brilliantly achieved emblem of the Renaissance, persistently confuses matter and spirit in a most blasphemous manner, for having no true belief in Christian immortality, he yet tries to secure himself a kind of bizarre life after death. Browning's many citations of types in the poem reveal his speaker continually misinterpreting heavenly spiritual matters which he appropriates and misapplies to his passionate yearning to make himself immortal. As George Monteiro has pointed out, "in ordering his tomb -- and the entire poem is organized around this piece of business -- the Bishop in effect parodies the Lord's command to Moses to build him a sanctuary: "According to all that I show thee, after the pattern of the tabernacle" (Full text of article). The Bishop, who sees himself as "an object worthy of worship", wishes his tomb to be constructed of stones from the Tabernacle, moreover, which were types of Heaven. Furthermore, the very details, such as the nine pillars supporting his tomb, turn out to be allusions to passages in Exodus which were commonly read as prefigurative images of Heaven as well. "Without hope for personal salvation and with no faith in the Christian Resurrection, the Bishop reduces references to John the Baptist and the Madonna to nothing more than aesthetic comparisons for his beloved lapis lazuli. At the same time, taking over metaphors which emblematize salvation, he attempts to remake them into the letter of an earthbound immortality of sorts"(5). We may add that the Bishop's many blasphemies find their center in his complete inability to comprehend the nature of matter, spirit and the relationship between them. In particular, he cannot interpret the literal expression of spiritual matters properly. Augustine's Confessions tell that during his earlier Manichaean stage when he accepted the sect's belief in philosophical materialism, he could not conceive symbolic interpretation, and that as he came to believe in a world of the spirit, he also came to accept and understand symbolic reading of texts. In fact, the connection of the two remains so close for Augustine that he terms "spiritual" what we today would subsume under the broad category "symbolical" (6). Browning's Bishop finds himself in the predicament of a Manichaean who can only accept the material and yet passionately desires immortality which requires a belief in spirituality. As a result, he collapses matter and spirit into each other, now calling upon the capacities of the one and now the other. This fusion and confusion of states of being which his passionate desire for immortality produces, is well suited to the psychological state of a dying man, and perhaps this suitability provides another reason why Browning chose to set this character portrait within the context of a death-bed scene. Related materials The Bishop's Deathbed Vision: Pan, Praxed and Preaching References Monteiro, George. "The Apostasy and Death of St. Praxed's Bishop." Victorian Poetry. 8 (1970): 216. (Full text of article) A fictional Renaissance bishop lies on his deathbed giving orders for the tomb that is to be built for him. He instructs his “nephews”—gperhaps a group of younger priests—on the materials and the design, motivated by a desire to outshine his predecessor Gandolf, whose final resting place he denounces as coarse and inferior. The poem hints that at least one of the “nephews” may be his son; in his ramblings he mentions a possible mistress, long since dead. The Bishop catalogues possible themes for his tomb, only to end with the realization that his instructions are probably futile: he will not live to ensure their realization, and his tomb will probably prove to be as much of a disappointment as Gandolf’s. Although the poem’s narrator is a fictional creation, Saint Praxed’s Church refers to an actual place in Rome. It is dedicated to a martyred Roman virgin. Form This poem, which appears in the1845 volumeDramatic Romances and Lyrics, represents a stylistic departure for Browning. The Bishop speaks in iambic pentameter unrhymed lines—blank verse. Traditionally, blank verse was the favored form for dramatists, and many consider it the poetic form that best mimics natural speech in English. Gone are the subtle yet powerful rhyme schemes of “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister” or “My Last Duchess.” The Bishop, an earthly, businesslike man, does not try to aestheticize his speech. The new form owes not only to the speaker’s earthy personality, but also his situation: he is also dying, and momentary aesthetic considerations have given way to a fervent desire to create a more lasting aesthetic monument. Commentary Poetry has always concerned itself with immortality and posterity. Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example, repeatedly discuss the possibility of immortalizing one’s beloved by writing a poem about him or her. Here, the Bishop shares the poet’s drive to ensure his own life after death by creating a work of art that will continue to capture the attention of those still living. He has been contemplating the issue for some time, as shown by his discussion of Gandolf’s usurpation of his chosen burial spot. His preparation has spanned years: he reveals that he has secreted away various treasures to be used in the monument’s construction, including a lump of lapis lazuli he has buried in a vineyard. The discussion as a whole reveals a fascinating attitude toward life and death: we come to see that the Bishop has spent so much of his time on earth preparing not for his salvation and afterlife, but for the construction of an earthly reminder of his existence. This suggests that the Bishop lacks religious conviction: if he were a true Christian, the thought of an eternal life in Heaven after his death would preclude his tomb-building efforts. Obviously, too, the Bishop does not expect to be remembered for his leadership or good deeds. And yet the monument he plans will be a work of magnificent art. Thus, as a whole, the poem reminds us that often the most beautiful art results from the most corrupt motives. Again, coming to this conclusion, Browning prefigures writers like Oscar Wilde, who made more explicit claims for the separation of art and morality. Despite the Bishop’s rough speech and dying gasps, this poem achieves great beauty. Part of this beauty lies in its attention to detail and the cataloguing of the various semiprecious stones that are to line the tomb. Natural history provided endless fascination for the Victorians, and the psyche of the period gave special prominence to the notion of collecting.Collecting offers a way to gather together objects of beauty without necessarily having to involve oneself in the act of creation. Instead, the collector can just gather bits of nature’s—or God’s—handiwork. Indeed, this notion of collecting provides an analog for Browning’s employment of dramatic monologues like this one: in their way, they resemble found objects, the speeches of characters he has just “stumbled across.” The poems are thus neither moral nor immoral; they just are. By taking such an attitude Browning may be trying to move beyond speculations on the moral dangers of modern, city-centered life, focusing more on anthropological than philosophical or religious aspects of existence. The poem ends with the Bishop’s vision of his corpse’s decay. The image hints at an underlying commonality of experience, a commonality more fundamental than any social power structures or aesthetic ambitions. While the notion of death as an equalizer may seem nihilistic, it can also prove liberating; for indeed, it relieves the Bishop, and implicitly Browning, of the burden of posterity. Form o The poem is in the form of a dramatic monologue. This made clear from the use of 'I' and his emotions coming through to the reader of panic, 'Do I like, am I dead?' Browning uses the dramatic monologue form a lot in his poems such as in The Patriot. o The dramatic monologue helps to emphasise the confusion and materialism of the Bishop who is the voice of the whole poem, 'I know not, I' ...' Ellipses are available to use because the dramatic monologue gives us the point of view from the Bishop. Structure o The poem is in real time chronological order making the Bishop's speech seem more like it is happening now. o There is no structure to the poem: it is one long stanza. The fact the poem has no structural stanzas and features ellipses illustrates how the Bishop's mind is wandering making the poem sound more like one long ramble. o There is no use of rhyming because it is the Bishop's random thoughts and to add to the realistic nature of this poem, his thoughts do not rhyme. o Structurally, the poem ends where it begins. The poem started by mentioning how 'Old Gandolf' envied the Bishop and that the mistress was 'so fair she was!' Ending the poem where it started produces a circular motion to the poem. However, there is no progression or development in the poem. o The poem has a circular motion but the development of the poem itself is dead, still: very much like the Bishop. o There is use of irregular line lengths making clear the Bishop is confused. o The structure and lack of coherency can be seen to reflect upon the Bishop's life. The poem is packed full of ideas from the Bishop's mind wandering creating the sense of materialism. Therefore, like his personality, the structure helps to make his poem an object owned by the Bishop strengthening his materialistic trait. The poem is divided by themes: o Rivalry with Gandolf. o Relationship with his sons. o Making the tomb beautiful. o Worried about his possessions. o Worried about death. Language o The Bishop starts by stating that his name shouldn't be in vanity, 'Vanity, saith the preacher, vanity!' He's vain with this being his last sermon. o Ellipses are used, 'sons mine...ah God'. This shows his is thinking making his speech less coherent. o The fact he asks for people to 'Draw round my bed' shows he's in the interior of a church. o 'Old Gandolf' was someone who envied him because the Bishop had the mistress: not Gandolf. o Early on, Browning establishes the character of the Bishop that he is somebody who wants to possess things. o The fact he is questioning life, 'Life, how and what is it?' suggests he has problems accepting Christian beliefs. This makes clear he is not a natural Bishop. o There is the use of long vowel sounds, 'dying by degree', to echo his long death. o 'Saint Praxed' is a virgin female Saint. o The repetition of 'Peace, peace' emphasises that peace is what he wants. o He comes across as very competitive, 'With tooth and nail to save my niche, ye know'. He has a devotion to have things the way he wants. o There is the use of a caesura, 'Draw close: that' to enable the sons to draw closer to the Bishop. o The Bishop talks to his sons, 'My sons, ye would not be my death? Go dig'. o Lots of ellipses are used throughout the poem '...' to make clear his wondering incoherent mind. o His sons are portrayed as selfish, 'That brave Frascati villa with its bath'. St Praxed in a glory, and one Pan Ready to twitch the Nymph's last garment off, And Moses with the tables ... but I know Ye mark me not! What do they whisper thee The Bishop here is in a playful mood showing his elaborate range of emotions before he dies and his confusion. With the help of another ellipsis, he wants Moses to be by him while he dies which is inappropriate. He believes he is important enough to have somebody of importance such as Moses to be there while he dies. o He addresses his boys directly, 'Nay, boys, ye love me - all jasper , then!' o 'And have I not St Praxed's ear to pray / Horses of ye, and brown Greek manuscripts' The Bishop is raising himself to the same level as a Saint saying people will listen and so on. o 'That's if ye carve my epitaph alright, / Choice Latin, picked phrase, Tully's every word'. He wants a poet to write an epitaph for him as he feels worthy enough. This identifies the Bishop as being arrogant. o 'And see God made and eaten all day long'. Here is a Catholic belief as well as examples of his individual's corrupt materialism. o 'Do I live, am I dead? There, leave me, there!' There is the use of exclamations throughout to hint towards credibility. o He is starting to not make sense 'ye have stabbed me with ingratitude' which makes the reader foreshadow a death approaching. o He starts to have nightmares about death, 'Gritstone, a-crumble! Clammy squares which sweat'. His visceral nightmares are to do with his body too. o He says there is nothing else to enjoy 'And no more lapis to delight the world!' This is something not what Bishops do. o 'Well, go! I bless ye. Fewer tapers there'. The Bishop blesses his sons and states that there are less tapers (slender candle). This can be seen as the light of life and that the candles represent God. If there are few tapers, there are less prayers meaning God in not around. o He worries if he is going to go to Heaven or Hell as he hasn't always done his religious duties. o 'Ay, like departing altar-ministrants'. Here he is describing his sons with the use of a simile. It is picturesque and graphic as they are leaving the Bishop quietly trying not to disturb him while they walk out. o The word 'peace' has a long vowel sound adding to the peace and silence. o The last line 'As still he envied me, so fair she was!' talks about the Mistress. It is at the end to show how much he loves her. This emphasises the rivalry between him and Gandolf and how he doesn't think like a Bishop. His thoughts are venial. He needs to be repentance saying sorry for what he has done wrong in life. However, he never says sorry strengthening the view that the Bishop think he is always right. "The Bishop Orders his Tomb at St. Praxed's Church" SUMMARY/STRUCTURE: In this poem, a Bishop provides specific instructions to his nephews as to his burial in a certain niche at St. Praxed's Church. Besides the details of these instructions, the Bishop reveals a rivalry with one "Old Gandolf" over a woman, whom the Bishop seems to have won in the end. The instructions reveal that the Bishop has a aggressively high view of himself--he wishes his nephews to place lapis-lazuli between his knees as if he were God with a globe. By the end of the poem, however, the Bishop admits that his instructions are probably futile, and admits that in death such things are not for him to ensure. The speech is in blank verse and roughly iambic pentameter. BACKGROUNDS/READINGS/CRITICAL APPROACHES: Armstrong argues that this poem combines "extreme intellectual and epistemological sophistication and an extreme commitment to the voracious power of anarchic, libidinal, emotion, and desire." This seems similar to the contrast I mentioned in "My Last Duchess" between logical speech and violent force. This poem was specifically admired by Ruskin, who felt that it perfectly expressed his notion of the "grotesque." Summary A fictional Renaissance bishop lies on his deathbed giving orders for the tomb that is to be built for him. He instructs his “nephews”—gperhaps a group of younger priests—on the materials and the design, motivated by a desire to outshine his predecessor Gandolf, whose final resting place he denounces as coarse and inferior. The poem hints that at least one of the “nephews” may be his son; in his ramblings he mentions a possible mistress, long since dead. The Bishop catalogues possible themes for his tomb, only to end with the realization that his instructions are probably futile: he will not live to ensure their realization, and his tomb will probably prove to be as much of a disappointment as Gandolf’s. Although the poem’s narrator is a fictional creation, Saint Praxed’s Church refers to an actual place in Rome. It is dedicated to a martyred Roman virgin. Form This poem, which appears in the1845 volumeDramatic Romances and Lyrics, represents a stylistic departure for Browning. The Bishop speaks in iambic pentameter unrhymed lines—blank verse. Traditionally, blank verse was the favored form for dramatists, and many consider it the poetic form that best mimics natural speech in English. Gone are the subtle yet powerful rhyme schemes of “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister” or “My Last Duchess.” The Bishop, an earthly, businesslike man, does not try to aestheticize his speech. The new form owes not only to the speaker’s earthy personality, but also his situation: he is also dying, and momentary aesthetic considerations have given way to a fervent desire to create a more lasting aesthetic monument. Commentary Poetry has always concerned itself with immortality and posterity. Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example, repeatedly discuss the possibility of immortalizing one’s beloved by writing a poem about him or her. Here, the Bishop shares the poet’s drive to ensure his own life after death by creating a work of art that will continue to capture the attention of those still living. He has been contemplating the issue for some time, as shown by his discussion of Gandolf’s usurpation of his chosen burial spot. His preparation has spanned years: he reveals that he has secreted away various treasures to be used in the monument’s construction, including a lump of lapis lazuli he has buried in a vineyard. The discussion as a whole reveals a fascinating attitude toward life and death: we come to see that the Bishop has spent so much of his time on earth preparing not for his salvation and afterlife, but for the construction of an earthly reminder of his existence. This suggests that the Bishop lacks religious conviction: if he were a true Christian, the thought of an eternal life in Heaven after his death would preclude his tomb-building efforts. Obviously, too, the Bishop does not expect to be remembered for his leadership or good deeds. And yet the monument he plans will be a work of magnificent art. Thus, as a whole, the poem reminds us that often the most beautiful art results from the most corrupt motives. Again, coming to this conclusion, Browning prefigures writers like Oscar Wilde, who made more explicit claims for the separation of art and morality. Despite the Bishop’s rough speech and dying gasps, this poem achieves great beauty. Part of this beauty lies in its attention to detail and the cataloguing of the various semiprecious stones that are to line the tomb. Natural history provided endless fascination for the Victorians, and the psyche of the period gave special prominence to the notion of collecting.Collecting offers a way to gather together objects of beauty without necessarily having to involve oneself in the act of creation. Instead, the collector can just gather bits of nature’s—or God’s—handiwork. Indeed, this notion of collecting provides an analog for Browning’s employment of dramatic monologues like this one: in their way, they resemble found objects, the speeches of characters he has just “stumbled across.” The poems are thus neither moral nor immoral; they just are. By taking such an attitude Browning may be trying to move beyond speculations on the moral dangers of modern, city-centered life, focusing more on anthropological than philosophical or religious aspects of existence. The poem ends with the Bishop’s vision of his corpse’s decay. The image hints at an underlying commonality of experience, a commonality more fundamental than any social power structures or aesthetic ambitions. While the notion of death as an equalizer may seem nihilistic, it can also prove liberating; for indeed, it relieves the Bishop, and implicitly Browning, of the burden of posterity. The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church, poem considered to be the first blank verse dramatic monologue in English, by Robert Browning, published in the collection Dramatic Romances and Lyrics (1845). The poem is a character study of a powerful, worldly prince of the Roman Catholic Church at the time of the Renaissance. The dying bishop is surrounded by his “nephews,” who are really his illegitimate sons. The prelate asks especially that his funeral be more elaborate than that of his rival in life and love, Fra Gandolf. Ideas about the poetry: - The blank verse of the poem is used to reflect speech - the speaker, a Bishop, is dying and therefore his speech often is repetitive, unstructured and rambling. - Browning, at this stage in his life, was not religious and therefore parodies, or attacks, the Catholic Church and a Religious figure. Later on in his life, Browning became more understanding of faith and we see a greater reflection in his work. - The speaker has commited many sins (despite his holy appearance); he has stolen items from the Church and buried them, he has fathered illegitmate sons (whom he calls his nephews) and he is more concerned about the material wealth of his tomb than his natural reward of Heaven. - Throughout we are left to question the moral hypocracy of the speaker. - The speaker is only concerned with beating his rival in life and love, Gandalf. - The irony of the poem is that the speaker, whilst concerned about his material possessions, will ultimately never live to see his tomb - this is something he comes to realise and adds to his rambling speech. - Browning is experimenting with poetic form and structure - something we see less of in his later works. A useful site: http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/rb/bishop/index.html George Monteiro has pointed out, "in ordering his tomb -- and the entire poem is organized around this piece of business -- the Bishop in effect parodies the Lord's command to Moses to build him a sanctuary: "According to all that I show thee, after the pattern of the tabernacle" (Exodus xxv.9)" Iambic Pentameter but how regular? It starts off-kilter! Mosaic of Pope Paschal I (possible inspiration for the Bishop in the poem) Interior of Basillica of St. Praxedes, in Rome.

![An approach to answering the question about Elizabeth Bishop[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008032916_1-b08716e78f328a4fda7465a9fffa5aba-300x300.png)