ap literary terms#1 - AP English Literature and Composition

advertisement

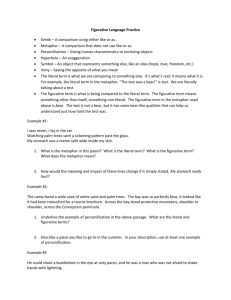

AP English Lit. Terms 1 Metaphorical Devices & Imagery Hilltop High School Mrs. Demangos Metaphor A figure of speech in which an implicit comparison is made between two things essentially unlike. It may take one of four forms: 1. That in which the literal term and the figurative term are both named 2. That in which the literal term is named and the figurative term implied 3. That in which the literal term is implied and the figurative named 4. That in which both the literal and the figurative terms are implied. Metaphor That in which the literal term and the figurative term are both named: “Life’s but a walking shadow” Figurative=Literal shadow=life yard=sorrow “Sorrow is my own yard…” 1 Metaphor That in which the literal term is named and the figurative term implied: “Out in the porch’s sagging floor, Leaves got up in a coil and hissed…” 2 Literal=Figurative Leaves=Snake “hissed” Metaphor That in which the literal term is implied and the figurative named “It sifts from Leaden Sieves— It powders all the Wood. It fills with Alabaster Wool The Wrinkles of the Road—” 3 Literal=Figurative It(snow)=wool Metaphor That in which both the literal and the figurative terms are implied. “It sifts from Leaden Sieves— It powders all the Wood. It fills with Alabaster Wool The Wrinkles of the Road—” 4 Literal=Figurative It(snow)=(flour)sifts Simile Simile and metaphor are both used as a means of comparing things that are essentially unlike. In a simile the comparison is expressed by the use of some word or phrase, such as like, as, than, similar to, resembles, seems. “Harlem” by Langston Hughes What happens to a dream deferred? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? like a syrupy sweet? Or fester like a sore— Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. And then run? Or does it explode? What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Simile: Deferred dream shrivels like a raisin Simile: Deferred dream becomes diseased, infected like a sore Personification Personification consists in giving the attributes of a human being to an animal, an object, or a concept. It is a subtype of metaphor. Personification When autumn is described as a harvester “sitting careless on a granary floor” or “on a halfreaped furrow sound asleep”, Keats is personifying a season. “To Autumn” by John Keats Personification When Sylvia Plath makes a mirror speak and think, she is personifying an object. Though the mirror speaks and thinks, we continue to visualize it as a mirror. Mirror by Sylvia Plath Archetype From the Greek arkhetupos, meaning “first molded as a pattern.” It is often used to refer to characters, plots, themes, and images that recur throughout the history of literature, both oral and written. Archetypes are recognized as designs or patterns. Archetype A pattern or model of an action (such as lamenting the dead), a character type (rebellious youth), or an image (paradise as a garden) that recurs consistently enough in life and literature to be considered universal. Archetype Although the term archetype has long been used in its most general sense, the psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, gave it new meaning. Jung theorized that certain ideas, actions, and images—rivalry between brothers, for example—arose out of early experiences of the human race, passed along through the “collective subconscious of mankind”, and are present in the subconscious of every individual. Archetype According to Jung, these archetypes emerge in the imagery of dreams and also in myths and other literature. Some archetypes are used so often in certain literary genres that they become conventions, or distinguishing features of the genre. Allusion A figure of speech that makes a brief reference to a historical or literary figure, event, or object. Biblical allusions are frequent in English literature. Ex. In Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, “A Daniel come to judgment.” Allusion Strictly speaking, allusion is always indirect. It seeks, by tapping the knowledge and memory of the reader, to secure a resonant emotional effect from the associations already existing in the reader’s mind. Ex. Herman Melville names a ship the Pequod in Moby-Dick. The reader, knowing the Pequod tribe to be extinct, will suspect the vessel to be fated for extinction. Allusion The effectiveness of allusion depends on a body of knowledge shared by writer and reader. Complex literary allusion is characteristic of much modern writing, and discovering the meaning and value of the allusions is frequently essential to understanding the work. Metonymy Greek for “a change of name”. Substitution of associated word for word itself. metonymy is a figure of speech. It substitutes the name of a related object, person, or idea for the subject at hand. Example: Crown- substituted for monarchy The White House- for the President of the U.S. Shakespeare- for the works of Shakespeare the Turf- for horse racing. Synecdoche Greek for “taking together”. A figure of speech in which a part of something stands for the whole thing. Synecdoche is a form of metonymy. Example: wheels in “I’ve got wheels.” Stands for car. hands in “All hands on deck!” Stands for sailors. threads as in “Nice threads!” Stand for clothes. Motif Recurrent image, idea, word, phrase, action, object, situation, or theme in specific piece of literature. It can appear in various works or throughout the same work. When applied to several different works, motif refers to a recurrent theme, such as the CARPE DIEM motif—the idea that life is short, time is fleeting, and one must make the most of the present moment. Example: Robert Herrick’s poem “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time.” Motif When applied to a single work, motif refers to a repetition that tends to unify the work by bringing to mind its earlier occurrences and the impressions that surround them. Example: the periodic striking of clocks in Virginia Wolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway Example: the repetition of patterns—of a garden, a dress, a fan, and of life itself in Amy Lowell’s poem “Patterns.” Symbol An object, character, figure, or color that is used to represent an abstract idea or concept. For example: the two roads in Robert Frost’s poem, “The Road Not Taken” symbolize the choice between two paths in life. Unlike an emblem, a symbol may have different meanings in different contexts. Symbol Some symbols come into a story from a shared language or symbols. Traditional symbolic associations: Dawn of hope Dark forest of evil Clay with death Water with fertility Light for knowledge or enlightenment. Symbol Some symbols have a special personal meaning for the writer. Example: Seamus Heaney—imaginative power staked in the image of the pump: the pump, like his poetry, taps hidden springs to conduct what is sustaining and life-giving; it is a symbol of nourishment. Symbol Literary An symbols are rich in associations. ancient symbol in Western culture is the garden: the Garden of Eden was a scene of innocence and happiness, before the fall of Adam. It is a symbol of nature seen as fruitful and life-sustaining. It may suggest the oasis in the desert. Symbol Symbols may be ambiguous. Example: in Melville’s Moby Dick the mythic white whale stands for everything that is destructive in nature—the whale destroys the ship. At other times, it stands for everything that is serenely beautiful in nature. Symbol Symbols acquire their full meaning in the context of the story. Example: In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, The Scarlet Letter, the letter A for adultery becomes a symbol of the consciousness of guilt, of our doubts about who is truly guilty. Image Sensory A detail word, phrase, or figure of speech that addresses the senses, suggesting mental pictures of sights, sounds, smells, tastes, feelings, or actions. Image Images offer sensory impressions to the reader and also convey emotions and moods through their verbal pictures. Sight=visual imagery Sound=auditory imagery Taste=gustatory imagery Touch=tactile imagery Smell=olfactory imagery Abstract/Concrete Classifications of imagery. For instance, calling a fruit "pleasant" or "good" is abstract, while calling a fruit "cool" or "sweet" is concrete. The preference for abstract or concrete imagery varies from century to century. Abstract/Concrete Philip Sidney praised concrete imagery in poetry in his 1595 treatise, Apologie for Poetrie. A century later, Neoclassical thought tended to value the generality of abstract thought. In the early 1800s, the Romantic poets like Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley once again preferred concreteness.