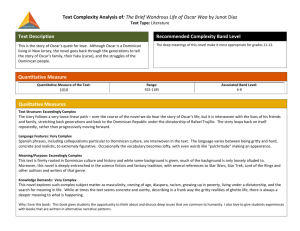

Chapter IV: Dominican-American Cultural Identity in Oscar Wao

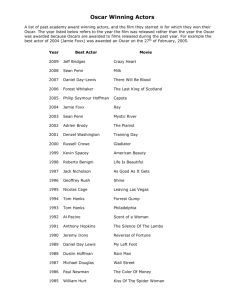

advertisement