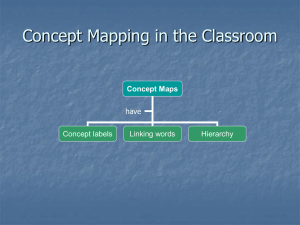

Concept Maps

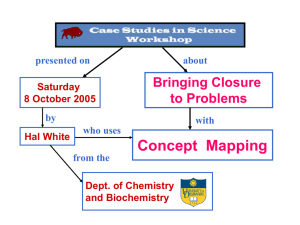

advertisement

Gabe Mydland & Mark Geary TIE09 CONCEPT MAPS WHAT DOES IT MEAN WHEN A STUDENT SAYS, I UNDERSTAND?.... DOES IT MEAN THE SAME THING TO HIM OR HER THAT IT DOES TO ANOTHER STUDENT OR TO YOU?..… HOW CAN YOUR STUDENTS DEMONSTRATE THEIR UNDERSTANDING TO YOU? Requires negotiated meaning for meaningful learning. Adults and kids in two different worlds “Hardware handshake” Common vocabulary Recalled information may appear in slightly different form. Students Often are challenged with Summarizing critical information, Describing concepts, and/or Organizing ideas in useful ways New Subject Matter Many times leaves students without any way to relate new information with existing knowledge Constructivist Learning Theory The understanding of content is linked with the ability to appreciate the interrelationships between different kinds of information AND Integrate this data into the students existing knowledge framework Successful Students Can distinguish the differences between things AND Understand the relationships between ideas or concepts Concept Maps Show the relationships between ideas Link concepts (nodes) with lines to represent relationships (proposition s) Concept Maps Provide us with a “window into students’ minds.” Concept Maps Replicate how information is organized and represented in memory Concept Maps… Transform student s into an active learner Encourages students to become self-directed learners Result in greater confidence in the comprehension of new material, and help to shrink the gap between theory and practice in clinical settings Concept Maps Develop skills in the areas of Critical thinking, Organization of information, Understanding of complex relationship, and Integration of theoretical knowledge Concept Maps Require students to Extract and focus on important ideas, Think about how these concepts are related, and Organize such information into an “integrated structure.” References De Simone, C. (2007). Applications of Concept Mapping. College Teaching , 55 (1), 33-36. Harpaz, I. B. (2004). Concept Mapping: An educational strategy for advancing nursing education. Nursing Forum , 27 -- 36. Kinchin, I. (2006). Concept mapping , PowerPoint, and a pedaogy of access. Jouranl of Biological Information , 40 (2), 79-83. Shaverlson, R. J., Ruiz-Primo, M., & Wiley, E. W. (2005). Windows into the Mind. Higher Education, 49, 413-430. Concept Map resources The following slides represent some of the best we have seen from other presentations. They are not the work of Mark or Gabe. When we find the source, we’ll share it. Stages in the Construction of a Concept Map Brainstorming Stage Organizing Stage Layout Stage Linking Stage Revising Stage Finalizing Stage Brainstorming Stage List any and all terms and concepts associated with the topic of interest. Write them on bubbl.us, one word or phrase per note. Or use cmap.ihmc.us to search for a concept map from around the world. Don't worry about redundancy, relative importance, or relationships at this point. The objective is to generate the largest possible list. Organizing Stage Spread concepts on a table or blackboard so that all can be read easily. Create groups and sub-groups of related items. Try to group items to emphasize hierarchies. Identify terms that represent higher categories and add them. Feel free to rearrange items and introduce new items omitted initially. Some concepts will fall into multiple groupings. This will become important in the linking stage. Layout Stage Arrange terms so that they represent your collective understanding of the interrelationships and connections among groupings. Use a consistent hierarchy in which the most important concepts are in the center or at the top. Within sub-grouping, place closely related items near to each other. Think in terms of connecting the items in a simple sentence that shows the relationship between them. Feel free to rearrange things at any time during this phase. Do not expect your layout to be like that of other groups. Linking Phase Use lines with arrows to connect and show the relationship between connected items. Write a word or short phrase by each arrow to specify the relationship. Many arrows can originate or terminate on particularly important concepts. Revising Stage Carefully examine the draft concept map. Rearrange sections to emphasize organization and appearance. Remove or combine items to simplify. Consider adding color or different fonts. Discuss any aspects where opinions differ Finalizing the Concept Map After your group has agreed on an arrangement of items that coveys your understanding, convert the concept map into a permanent form that others can view and discuss. Be creative in a constructive way through the use of colors, fonts, shapes. Evaluating Concept Maps Accuracy and Thoroughness. Are the concepts and relationships correct? Are important concepts missing? Are misconceptions apparent? Organization. Is the concept map laid out in a way that higher order relationships are apparent and easy to follow? Does it have a title? Appearance. Is the assignment done with care showing attention to details such as spelling and penmanship? Is it neat and orderly or is it chaotic and messy? Creativity. Are there unusual elements that aid communication or stimulate interest without being distracting? Uses of a Concept Map? Graphic organizer Displays hierarchy and connections among ideas/objects/people, etc. Diagnostic tool Displays understandings and misconceptions through placement of ideas/objects/people, etc. and the links forged between them. Planning tool Displays a break-down of simple or complex concepts/tasks/programs Concept Map of Concept Mapping Source: Learning How to Learn, Novak and Gowin Background Grew from Joseph D. Novak’s research at Cornell. Piagetian interviews Ausubel subsumption theory Constructivist? The more we learn and organize knowledge in a given domain, the easier it is to acquire and use new knowledge. Practice Novak’s instructions for building a concept map (Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge) 1. Identify a focus question that addresses the problem, issues, or knowledge domain you wish to map. Guided by this question, identify 10 to 20 concepts that are pertinent to the question and list these. Some people find it helpful to write the concept labels on separate cards or Post-itsTM so that they can be moved around. If you work with computer software for mapping, produce a list of concepts on your computer. Concept labels should be a single word, or at most two or three words. 2. Rank order the concepts by placing the broadest and most inclusive idea at the top of the map. It is helpful to reflect on your focus question to help decide the ranking of the concepts. Sometimes this process leads to modification of the focus question or writing a new focus question. 3. Work down the list and add more concepts as needed. 4. Begin to build your map by placing the most inclusive, most general concept(s) at the top. Usually there will be only one, two, or three most general concepts at the top of the map. 5. Next select the two, three, or four subconcepts to place under each general concept. Avoid placing more than three of four concepts under any one concept. If there seem to be six or eight concepts that belong under a major concept or subconcept, it is usually possible to identify some appropriate concept of intermediate inclusiveness, thus creating another level of hierarchy in your map. 6. Connect the concepts by lines. Label the lines with one of a few linking words. The linking words should define the relationship between the two concepts so that it reads as a valid statement or proposition. The connection creates meaning. When you hierarchically link together a large number of related ideas, you can see the structure of the meaning for a given subject domain. 7. Rework the structure of your map, which may include adding, subtracting, or changing superordinate concepts. You may need to do this reworking several times, and in fact this process can go on indefinitely as you gain new knowledge or new insights. This is where Post-itsTM are helpful, or better still, computer software for creating maps. 8. Look for crosslinks between concepts in different sections of the map and label these lines. Crosslinks can often help to see new, creative relationships in the knowledge domain. 9. Specific examples of concepts can be attached to the concept labels (e.g., golden retriever is a specific example of a dog breed.) 10. Concept maps could be made in many different forms for the same set of concepts. There is no one way to draw a concept map. As your understanding of relationships between concepts changes, so will your maps. Streamlined instructions Brainstorm concepts and individualize. Words or images will work. 2. Organize the concepts in terms of hierarchy of general to specific. 3. Map the concepts on paper with labeled links between them, adding or subtracting as needed to paint as complete a picture of understanding as possible. 1.