Russian Avant

advertisement

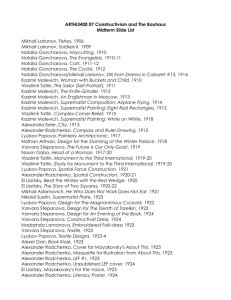

The Russian Avant-garde: Experiments in Abstraction Purpose • When the new century came, the quest for national identity caused an ambitious and aggressive change in every part of Russian culture. • There was a chauvinistic desire to beat the West at its own game. Russian Futurism • inspired by the writings of Marinetti, Russian Futurists sought to create a movement which would cause the Western artists to look to Russia for guidance • sought to create a format which was uniquely Russian in style • became increasingly used as a device of propaganda and a voice for social reform • brought to an end by the government's official endorsement of Socialist Realism The Role of Artists • saw their work as a reflection of the social, economic and cultural climate of the moment, and vehicles that could initiate change • disseminated their radical ideas which enabled new groups to evolve their own philosophies, keeping visual art in a constant state of development • appreciated the significant impact their ideas could have on society The Russian Avant-garde: Suprematism (1913 - 1919) Constructivism (1913 – 1921) Suprematism (1913 - 1919) • was a revolutionary art movement promoting pure aesthetic creativity, “the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art” • dispenses with subject matter, perspective, and traditional painting techniques • centers on the visual qualities of shape and space, free from the constraints of real world objectivity • presents an art of dynamic purity to stir emotions and promote contemplation • uses squares, rectangles, circles, triangles and the cross—taking cubist geometry to its logical conclusion of absolute geometric abstraction Kazimir Malevich (1878 – 1935) His Aim • to create work so pure and so abstract that it allowed you to transcend into quiet thought , beyond the object and into the spiritual • to free art from the burden of the object • to demonstrate that a painting can exist independent of any reflection or imitation of the real world Kazimir Malevich. The Harvest of the Century (1912). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying (1915). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Red Square (1915). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Boy with Knapsack—Color Masses In the Fourth Dimension (1915). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Composition (1915). Oil on canvas Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Painting (1915-16). Oil on canvas Kazimir Malevich. Suprematism (Supremus No. 58), 1916. Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Painting (1916). Oil on canvas Kazimir Malevich. Suprematism (1916-17). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Black Square (1923-29). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Black Circle (1923-29). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Black Cross (1923-29). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918) Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Suprematist Composition (1923-25). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Sportsmen (1928-30). Oil on canvas. Kazimir Malevich. Self-portrait (1933). Oil on canvas. Constructivism (1912 – 1921) • translated the 'spirit' of the machine age and the new society into a practical visual form • shifted its emphasis toward designing functional constructions which could benefit the emerging soviet state • ventured into the production of items beneficial to the new Russia, the materials used were appropriate to the product and process whether ceramics, clothing, posters or architecture • interested in an immediate application to create a new civilization in the Soviet Union, with art becoming the motor of the propaganda machine The Style • a purely non-objective approach in the making of artwork, • without reference to the real world • was essentially geometric, precise and almost mathematical; in fact a number of Rodchenko drawings were executed with compass and ruler • used squares, rectangles, circles and triangles as the predominant shapes in carefully composed artworks, whether drawing, painting, design or sculpture • emphasized the dominance of the world of machines and structures over nature Methods and Materials • dealt with such a wide range of materials that anything was possible; wood, celluloid, nylon, Plexiglas, tin, cardboard and early forms of plastic were used through a variety of constructing methods from glue through to welding • lacked the more engineered approach developed by International Constructivism • employed new materials, construction, and joining methods, including aluminum, electronic components and chrome-plating Vladimir Tatlin 1885-1953 Tatlin • began constructing relief sculptures in a variety of materials including tin, glass, wood and plaster • combined actual materials through careful construction, where the real space between them would be treated as a pictorial element, thus forcing their inter-relationship as an important aesthetic consideration • introduced space as a compositional factor, changing the face of modern sculpture • used suspended wire across the corner of a room, divorcing himself from the earthbound tradition of past sculpture Vladimir Tatlin. Nude (1910-14). Watercolor. Vladimir Tatlin. Sailor (1911). Watercolor. Vladimir Tatlin. Corner Relief (1915). Mixed media. Vladimir Tatlin. Counter Relief ( 1914-15). Iron, copper, wood, rope. Photograph of Tatlin Inaugurating Monument to Sofia Perovskaya, December 20, 1918, USSR Vladimir Tatlin. Monument to the Third International (1991-20). Wood, iron, and glass. Had the full-scale project been built, it would have been approximately 1300 feet high, the biggest sculptural form ever conceived by man. It was to have been a spiral metal frame tilted at an angle and encompassing a glass cylinder, cube, and cone. The various glass units, housing conferences and meetings, were to revolve, making a complete revolution once a year, once a month, and once a day. The structure would have served to steer the course of humanity on earth. Sculptural maquette of Monument to the Third International as it appeared on the Mayday parade in Moscow in 1926 Vladimir Tatlin. Letatlin (1932). Wood, cork, metal, silk, ball bearings, and whalebone. Vladimir Tatlin. Reconstruction of Letatlin (1929-31). Vladimir Tatlin. Letatlin (1932). Wood, cork, metal, silk, ball bearings, and whalebone. Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930) Vladamir Mayakovsky. Revolutionary Poster (1920). Vladamir Mayakovsky. Revolutionary Poster (1920). El Lissitzky (1890 – 1956) El Lissitzky. Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919). El Lissitzky. Untitled (Sketch for Roza Luxemburg’s Memorial), 1919-20. El Lissitzky. Proun AII (1920). Black ink, gouache, watercolor and graphite on tan cardboard. Proun is the name he gave his non-objective paintingconstructions, in which he experimented with the elements of contemporary geometric abstraction combined with perspective illusions. It is an acronym for “Project for the Affirmation of the New” in Russian. El Lissitzky. Proun 5a (1922). Distemper, tempera, varnish and pencil on canvas. El Lissitzky. Composition (1920). Black ink, gouache, watercolor and graphite on tan cardboard. El Lissitzky. Proun 19D (1922). Gesso, oil, collage, etc., on plywood. El Lissitzky. Proun G7 (1923). Distemper, tempera, varnish and pencil on canvas. Alexander Rodchencko 1891 - 1956 Alexander Rodchenko. Construction (1919). Oil on canvas. Alexander Rodchenko. Constructivist Collage to the Third International (1919). Collage of pasted papers. “Better pacifiers there were never, I’m prepared to suck forever. On sale everywhere.” Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Mayakovsky. The Best Nipple (1923). Gouache on photographic board mounted on cardboard. Alexander Rodchenko. Illustration for Mayakovsky’s Pro Eto (1923). Photomontage, pink and black paper on paper. “You should be ashamed of yourself—you’re still not on the list of Dobrolet stock holders. The whole country has an eye on this list. One gold ruble makes anyone a stockholder. . . .” Alexander Rodchenko. Dobrolet Advertising Poster (1923). Lithograph on paper. Alexander Rodchenko. Dobrolet Trademark (1923). Gouache on paper. Alexander Rodchenko. Design for Book Cover Incorporating the Word “Depot” (ca. 1925). Watercolor, tempera, pen and ink, and pencil on paper. Alexander Rodchenko. The Workers’ Club (1925). Alexander Rodchenko. Poster for Sergei Einstein’s film Battleship Potemkin (1925). Alexander Rodchenko. Worker’s suit (1925). Alexander Rodchenko. Conversation with the Finance Official on Poetry. Cover for the book by V. Mayakovsky (1926). Varvara Stepanova 1894-1958 Varvara Stepanova. Figure (1920). Gouache and pencil on illustration board. Varvara Stepanova. Collage (1919-20). Paper on paper. Varvara Stepanova. Tarelkin, costume design of the play Tarelkin’s Death by Sukhovo-Kobylin (1922). Gouache and blue pencil on paper. Varvara Stepanova. Design for men’s sportswear (1923). Gouache and Indian ink on paper. Varvara Stepanova Dress design for daytime (1924). Gouache and Indian ink on paper. Varvara Stepanova The Third Warrior (1925). Collage and India ink on paper. The End of Constructivism • The Soviet regime at first encouraged this new style. • However, beginning in 1921, constructivism (and all modern art movements) were officially disparaged as unsuitable for mass propaganda purposes Social Realism Karp Demyanovich Trokhlmenko. Stalin as an Organizer of the October Revolution. Oil on canvas Isaac Izrailevich Brodskiy. Vladimir Ilich Lenin (1924). Oil on cardboard. Vasili Filippovich Ivanov. Vladimir Ilich Lenin Speaking (1928). Oil on canvas. Peter Panteleimonovich Parkhet. Stalin at the 8th Conference of the Highest Council. Oil on canvas. Boris Eremeevich Vladimirski. Miner (1929). Oil on cardboard. Female Worker (1929). Oil on cardboard. Vladimir Gavrilovich Krikhatzkij: New Tractor (1929). Oil on cardboard.