Antony and Cleopatra - University of Warwick

advertisement

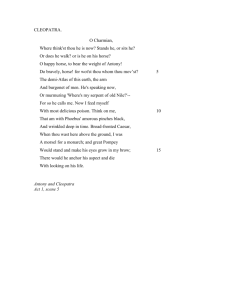

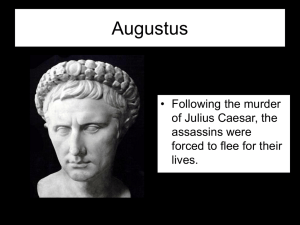

Suit the action to the word, the word to the action; with this special observance, that you o'erstep not the modesty of nature: for anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature; to show Virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure. (Hamlet, 3.2.17-24) The purpose of Plutarch when men have led reckless lives, and have become conspicuous, in the exercise of power or in great undertakings, for badness, perhaps it will not be much amiss for me to introduce a pair or two of them into my biographies, though not that I may merely divert and amuse my readers by giving variety to my writing. 6 Ismenias the Theban used to exhibit both good and bad players to his pupils on the flute and say, you must play like this one," or again, "you must not play like this one"; and Antigenidas used to think that young men would listen with more pleasure to good flute-players if they were given an experience of bad ones also. So, I think, we also shall be more eager to observe and imitate the better lives if we are not left without narratives of the blameworthy and the bad. This book will therefore contain the Lives of Demetrius the City-besieger and Antony the Imperator, men who bore most ample testimony to the truth of Plato's saying that great natures exhibit great vices also, as well as great virtues. Both alike were amorous, bibulous, warlike, munificent, extravagant, and domineering, and they had corresponding resemblances in their fortunes. For not only were they all through their lives winning great successes, but meeting with great reverses; making innumerable conquests, but suffering innumerable losses; unexpectedly falling low, but unexpectedly recovering themselves again; but they also came to their end, the one in captivity to his enemies, and the other on the verge of this calamity. Life not history Opening of Plutarch’s Life of Alexander (parallel life to Julius Caesar): My intent is not to write histories, but only lives. For the noblest deeds do not always show in men’s virtues and vices; but oftentimes a light occasion, a word, or some sport, makes men’s natural dispositions and manners appear more plain than the famous battles won wherein are slain ten thousand men, or the great armies, or cities won by siege or assault. Here’s sport indeed! Caesar rebukes Antony’s playfulness But to confound such time That drums him from his sport and speaks as loud As his own state and ours, ’tis to be chid – As we rate boys who, being mature in knowledge, Pawn their experience to their present pleasure, And so rebel to judgment. (1.4) Homo Ludens In Homo Ludens (1938), Huizinga identifies 5 characteristics that play must have: Play is free, is in fact freedom. Play is not “ordinary” or “real” life. Play is distinct from “ordinary” life both as to locality and duration. Play creates order, is order. Play demands order absolute and supreme. Play is connected with no material interest, and no profit can be gained from it. Play is a basic existential phenomenon, just as primordial and autonomous as death, love, work and struggle for power, but it is not bound to these phenomena in a common ultimate purpose. Play, so to speak, confronts them all – it absorbs them by representing them. We play at being serious, we play truth, we play reality, we play work and struggle, we play love and death – and we even play play itself. Eugen Fink, “The Oasis of Happiness: Toward an Ontology of Play,” Yale French Studies: 41 (1968): 19– 30. Wasting time Lust in idleness For do they not nourish idleness? And otia dant vitia, idleness is the mother of vice, and many vicious persons when they know not how any longer to be idle, for variety of idleness go to see plays. Do they not draw the people from hearing the word of God, and godly lectures? For you shall have them flock thick and three-fold to the play-houses, and with all celerity make speed to enter in them, lest they should not get place near enough unto the stage (so prone and ready are they to evil) when the temple of God shall remain bare and empty. I.G. ‘A Refutation of the Apology for Actors’ (1615) (repr. in Shakespeare’s Theater: A Sourcebook, ed Tanya Pollard, 2004: 267) Falsehood and going native The proof is evident, the consequent is necessary, that in stage plays for a boy to put on the attire, the gesture, the passions of a woman; for a mean person to take upon him the title of a prince, with counterfeit port and train; and by outward signs to show themselves otherwise than they are, and so within the compass of a lie, which by Aristotle’s judgment is naught of itself and to be fled. Stephen Gosson, Plays Confuted in Five Actions (1582) Cleopatra. Cut my lace, Charmian, come; But let it be: I am quickly ill, and well, So Antony loves. Antony. My precious queen, forbear; And give true evidence to his love, which stands An honourable trial. Cleopatra. So Fulvia told me. I prithee, turn aside and weep for her, Then bid adieu to me, and say the tears Belong to Egypt: good now, play one scene Of excellent dissembling; and let it look Life perfect honour. Antony. Cleopatra. You can do better yet; but this is meetly. Antony. Now, by my sword,— Cleopatra. And target. Still he mends; But this is not the best. Look, prithee, Charmian, How this Herculean Roman does become The carriage of his chafe. (1.3) You'll heat my blood: no more. Anti-theatrical Octavius The wild disguise hath almost / Antick’d us all (2.7.122) Enobarbus on Antony’s challenge to single combat: Yes, like enough high-battled Caesar will Unstate his happiness, and be stag’d to th’show Against a sworder… (3.13.29-31) Caesar: The time of universal peace is near… (4.6.4) Orientalism The First World war brought many Australian, British, New Zealand and colonial troops to Cairo. European Cairo was a madhouse because of the British and their self-indulgences. The prices began to rise steeply in Cairo while the British soldiers were enjoying things that they had never had before. The people in the countryside began to suffer greatly from poverty and malnutrition. It was so bad that during the year 1918 more people died than were born. Men at Work (3.1) VENTIDIUS: Caesar and Antony have ever won More in their officer than person […] Who does i’th’wars more than his captain can Becomes his captain’s captain. […] I’ll humbly signify what in his name, That magical word of war, we have effected; How, with his banners and his well-paid ranks, The ne’er-yet-beaten horse of Parthia We have jaded out o’th’field. (3.1) Infanticide Where art thou, death? Come hither, come! come, come, and take a queen Worthy many babes and beggars! (V.2) Cleopatra, know, We will extenuate rather than enforce: If you apply yourself to our intents, Which towards you are most gentle, you shall find A benefit in this change; but if you seek To lay on me a cruelty, by taking Antony's course, you shall bereave yourself Of my good purposes, and put your children To that destruction which I'll guard them from, If thereon you rely. I'll take my leave. For play Play can be experienced as a pinnacle of human sovereignty. Man enjoys here an almost limitless creativity… The player experiences himself as the lord of the products of his imagination – because it is virtually unlimited, play is an eminent manifestation of human freedom… plan can contain within itself… the clear apollonian moment of free self-determination. Eugen Fink, “The Oasis of Happiness: Toward an Ontology of Play,” Yale French Studies: 41 (1968): 19– 30 As a civilization becomes more complex, more variegated and more overladen, and as the technique of production and social life itself become more finely organized, the old cultural soil is gradually smothered under a rank layer of ideas, systems of thought and knowledge, doctrines, rules and regulations, moralities and conventions which have lost all touch with play. Civilization, we then say, has grown more serious; it assigns only a secondary place to playing. The heroic period is over, and the agonistic phase, too, seems a thing of the past. • (Huzuinga, Homo Ludens 75) Infinite jest Show me, my women, like a queen: go fetch My best attires: I am again for Cydnus, To meet Mark Antony: sirrah Iras, go. Now, noble Charmian, we'll dispatch indeed; And, when thou hast done this chore, I'll give thee leave To play till doomsday. Bring our crown and all.