File

advertisement

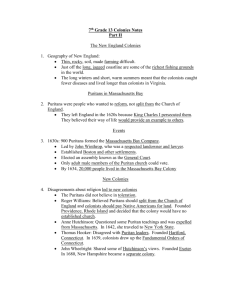

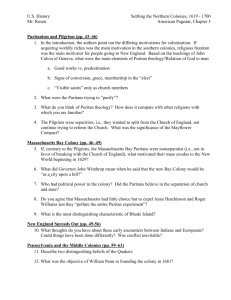

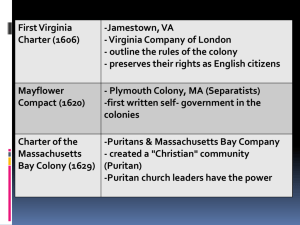

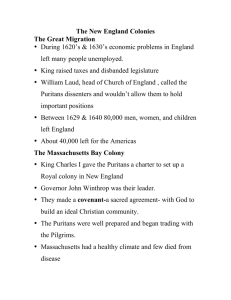

James L. Roark ● Michael P. Johnson Patricia Cline Cohen ● Sarah Stage Susan M. Hartmann The American Promise A History of the United States Fifth Edition CHAPTER 4 The Northern Colonies in the Seventeenth Century, 1601–1700 Copyright © 2012 by Bedford/St. Martin's I. Puritans and the Settlement of New England A. Puritan Origins: The English Reformation 1. Henry VIII and the English Reformation 2. Puritans • were Protestants who called for a genuine, thoroughgoing Reformation; Puritanism was less an organized movement than a set of ideals and religious principles that appealed to dissenting members of the Church of England; they sought to eliminate what they saw as the offensive features of Catholicism that remained in the Church of England, such as hierarchy and rituals 3. Waxing and Waning of Protestantism in England • in 1629 Charles I dissolved Parliament, where Puritans were well represented, and initiated aggressive anti-Puritan policies; many Puritans chose to emigrate, with the largest number going to America. B. The Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony 1. Pilgrims • endorsed separatism; they wanted to withdraw from the Church of England, which they considered hopelessly corrupt; they first moved to Holland in 1608. 2. William Bradford • leader of the Pilgrims, and he believed that America promised to better protect their children’s piety and preserve their community; separatists obtained permission to settle in the territory granted to the Virginia Company; 102 immigrants boarded the Mayflower in August 1620, and after eleven weeks at sea, they arrived in present-day Massachusetts. 3. Mayflower Compact 4. Plymouth settlement • settled at Plymouth and elected Bradford their governor; the first winter was devastating, and half of the settlers died; Wampanoag Indians rescued the settlement that spring; Squanto taught the settlers to grow corn and told them how to get fish; celebrated in the fall of 1621 with a feast of Thanksgiving attended by Chief Massasoit and other Wampanoags; the settlement remained precarious and failed to attract many other English Puritans. I. Puritans and the Settlement of New England C. The Founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony 1. Massachusetts Bay Company • 1629, a group of Puritan merchants and country gentlemen obtained a royal charter for the Massachusetts Bay Company • granted land for colonization in present-day Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, and upstate New York; a unique provision permitted the government of Massachusetts to be located in the colony rather than in England • Puritans went from oppressed minority to self-government. 2. John Winthrop • delivered his famous “city on a hill” sermon that proclaimed the Puritans’ colony would set a religious example for the rest of the world. 3. Early New England • strengthened colonists’ desire to obey God’s laws • more than 20,000 Puritans came to Massachusetts • by 1640, New England had one of the highest ratios of preachers to population in all of Christendom • on the whole, immigrants came from the middle ranks of English society; most were farmers or tradesmen • only one-fifth came as indentured servants; also unlike the Chesapeake, most immigrants arrived as families II. The Evolution of New England Society A. Church, Covenant, and Conformity 1. Puritan Protestantism • • • • believed that the church consisted of men and women who had entered into a solemn covenant with one another and with God derived from Calvinism; Puritans believed in predestination, that God had decided before the creation of the world which humans would receive eternal life; only God knew the identity of these fortunate individuals, known as the “elect” or “saints”; nothing a person did could alter his or her fate, but Puritans believed if a person lived a godly life that his or her behavior would reflect his or her status as one of God’s chosen few; Puritans thought that visible saints—people who passed tests of conversion and church membership—probably, but not certainly, were among God’s elect. 2. Church 3. Strict moral laws fines were issued for Sabbath-breaking activities such as working, traveling, or playing a flute; religious wedding ceremonies were outlawed; elaborate clothing and finery were prohibited. B. Government by Puritans for Puritanism 1. General Court-made the laws needed to govern the company’s affairs. 2. Freemen and “inhabitants” • • 1631, all male church members were deemed freemen; only freemen could vote for governor, deputy governor, and colonial officials; all other men were classified as “inhabitants”; they could vote, hold office, and participate fully in town government 3. “Town meeting” 4. Land distribution town founders apportioned land among themselves and any newcomers they permitted to join them; the physical layout of towns encouraged settlers to look inward toward their neighbors. II. The Evolution of New England Society C. The Splintering of Puritanism 1. Different visions of godliness 2. Roger Williams • argued that forcing non-Christians to attend church constituted “false worshipping” and “spiritual rape” • he argued that since only God knew the truth, New England should practice religious toleration; Winthrop banished him from the colony; he escaped deportation back to England and settled Rhode Island. 3. Anne Hutchinson • she expounded on the sermons of John Cotton, which stressed the covenant of grace, the idea that individuals could be saved only by God’s grace in choosing them to be in the elect, which contrasted to the covenant of works, the belief that behavior can bring salvation • Cotton’s sermons hinted that many Puritans were guilty of embracing Arminianism, or a belief in the covenant of works; Hutchinson agreed her lectures alarmed Winthrop, who believed she was subverting social order; • Winthrop referred to Hutchinson and her followers as antinomians, or people opposed to God’s law as set forth in the Bible and as interpreted by the colony’s leaders; elders accused her of the heresy of prophesy and excommunicated her in 1638. 4. Thomas Hooker • clashed with Winthrop over the constitution of the church; • he believed that men and women who lived godly lives should be admitted to church membership even if they had not experienced conversion; • this argument had political ramifications, as only church members could vote; Hooker led an exodus of more than 800 colonists to the Connecticut River Valley • founded Hartford and neighboring towns which, in 1639, adopted the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, a quasi-Constitution. II. The Evolution of New England Society D. Religious Controversies and Economic Changes • • • • • • • • 1. Puritan Revolution slows immigration to New England 2. New England’s economy Fewer boats to New England increased the prices on scarce English goods and cut off customers from colonial products; had to find domestic products fish became the most important export, and it stimulated colonial shipbuilding. 3. Puritanism is challenged Population continued to grow through natural increase, doubling every twenty years population grew faster than church membership; many children of “visible saints” failed to experience conversion and attain full church membership to solve this problem, in 1662, a synod of Massachusetts ministers established the Halfway Covenant allowed the unconverted children of visible saints to become “halfway” church members—they could baptize their infants but could not participate in communion or vote. New England still enforced piety, however, as evidenced by the treatment of Quakers with ruthless severity New England’s limited success in establishing a godly society undermined the appeal of Puritanism Salem witch trials only increased the gnawing doubt about the strength of Puritan New Englanders’ faith. III. The Founding of the Middle Colonies A. From New Netherland to New York 1. Dutch East India Company and Henry Hudson • 1609, the Dutch East India Company sent Hudson to look for a Northwest Passage to Asia; he sailed the Atlantic coast and traveled up the river that now bears his name. • company director Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan Island from the Manhate Indians for trade goods worth the equivalent of a dozen beaver pelts; New Amsterdam became the central trading center in New Netherland but did not attract many European immigrants were remarkably diverse in religious beliefs and ethnic origins compared to the English settlers in New England and the Chesapeake West India Company created resentment among the colonists by never allowing them to form a representative government; New Netherland became New York when the English demanded New Netherland governor Peter Stuyvesant surrender the area to the British; • • 2. New Netherland B. New Jersey and Pennsylvania 1. Duke of York subdivides his grant • • • • subdivided his land grant and gave the portion between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers to two of his friends the proprietors of this colony, New Jersey, quarreled and called in English Quaker William Penn to arbitrate their dispute. 2. William Penn settled the dispute and became interested in establishing a genuinely Quaker colony in America Quakers believed in an open, generous God who made his love equally available to all people; Quaker leaders were ordinary men and women, and women assumed positions of religious leadership; these beliefs and practices continually brought them into conflict with the English government; Penn remained on good terms with Charles II; partly to rid England of the Quakers, in 1681, Charles made Penn the proprietor of a new colony called Pennsylvania. III. The Founding of the Middle Colonies C. Toleration and Diversity in Pennsylvania 1. English Quakers flock to Pennsylvania • 1682 and 1685, nearly eight thousand immigrants arrived, most of whom were artisans, farmers, and laborers. 2. Ethnic diversity 3. Peace with the Indians • Penn was determined to live in peace with the Indians; he dealt with Indians fairly as an expression of his Quaker ideals; he instructed agents to purchase Indian land, respect their claims, and deal with them fairly. 4. Religiously tolerant • voters and officeholders had to be Christians, but the government did not compel settlers to attend church or levy taxes to maintain a state-sponsored church. 5. Evolution of local government • used civil government to enforce religious morality; he had extensive powers subject only to review by the king; he stressed that the exact form of government mattered less than the men who served in it. IV. The Colonies and the English Empire A. Royal Regulation of Colonial Trade 1. Navigation Acts • Acts of 1650, 1651, 1660, and 1663 set forth two fundamental rules governing colonial trade; • first, goods shipped to and from the colonies had to be transported in English ships using primarily English crews • second, certain enumerated products could only be shipped to England or to other English colonies • affected Chesapeake tobacco more than New England and middle colonies’ exports. 2. Colonial commerce regulated by royal supervision • defined by regulations that subjected merchants and shippers to royal supervision and gave them access to markets throughout the English empire • colonial goods counted for one-fifth of all English imports, and the colonies absorbed more than one-tenth of English exports. B. King Philip’s War and the Consolidation of Royal Authority • • • • • • • • • • 1. Monarchy seeks greater control over colonies Charles II took particular interest in harnessing Puritan New England; the opportunity for a royal investigation arose after King Philip’s War. 2. King Philip’s War 1675, warfare between Indians and colonists erupted in the Chesapeake and New England; colonists emerged triumphant from King Philip’s War; the war left New Englanders with an enduring hatred of Indians, a large war debt, and a devastated frontier. 3. Dominion of New England royal investigation concluded that the colonists had deviated from English rules; in 1684, an English court revoked the Massachusetts charter two years later, royal officials incorporated Massachusetts and the other colonies north of Maryland into the Dominion of New England, governed by Sir Edward Andros. In England in 1688, the Glorious Revolution reasserted Protestant power and emboldened colonial uprisings against royal authority in Massachusetts, New York, and Maryland in 1689, the rebellious colonists destroyed the Dominion of New England, overthrew Andros, and reestablished the former charter governments in both Massachusetts and New York; rebel governments did not last long, and the crown soon reestablished royal control of the colonies; in 1691, Massachusetts became a royal colony, and landowners, rather than church members, could vote in colony-wide elections. 4. Threats from New France worried that the Catholic colony of New France menaced frontier regions by encouraging Indian raids and by competing for the lucrative fur trade; when the English colonies were distracted by the Glorious Revolution, the French attacked villages in New England and New York in King William’s War the war ended inconclusively, but it reminded colonists that along with English royal government came a welcome measure of military security.