Hedda Gabler

advertisement

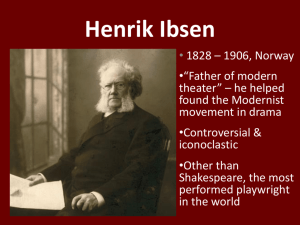

Henrik Ibsen | Hedda Gabler Realism Mimesis: Aristotle claimed all art is – or should be mimetic, representing/imitating life. Realism and Greek tragedy Plutarch, Moralia: ‘Sophocles used to say that having played through the magniloquence of Aeschylus, and the sharp artificiality of his own manner, he turned finally to the style of ordinary speech [lexis], the best and most expressive of character.’ Euripides in Aristophanes’s Frogs: “I wrote about everyday things, things the audience knew about and could take me up on if necessary. I didn’t try to bludgeon them into submission with long words.” Realism Realism in late nineteenth-century theatre At the end of the nineteenth century, from about 1870 onwards, a movement emerged across Europe which expressly aimed to create dramas that: •approximated everyday speech and situation. •confronted to the social and domestic problems of contemporary life. •constructed scenery that reproduced the customary environs of the people represented with the greatest fidelity a possible. •demanded a new type of actor, one who spoke and moved naturally. A pan-European movement: Ibsen (Norway), Émile Zola (France), early August Strindberg (Sweden), Gerhart Hauptmann (Germany), Anton Chekhov, and Maxim Gorky (Russia). Around the same time novelists – Balzac, Flaubert, Henry James, Tolstoy – were attempting much the same thing. Realism and Modernism Ibsen often called “the father of realism”. “The effect of the play depends a great deal on making the spectator feel as if he were actually sitting, listening, and looking at events happening in real life.” (Henrik Ibsen on Ghosts)* Important to see realism as a precursor or early stage of modernism. Realism: •Revolts against romanticism and melodrama. •Resists and dissects the conventions and ideologies of bourgeois culture. •Reveals modern life to be vacuous, sordid, absurd – even inherently tragic. * In Letters and Speeches, ed. and trans. Evert Sprinchorn (New York: Hill, 1964), p. 222. Realism and Naturalism: Spot the difference? “Naturalism”: a term first used by Émile Zola in his essay “Naturalism in the Theatre” (1881): •“Naturalism, in literature … is the return to nature and to man, direct observation, correct anatomy, the acceptance and depiction of that which is.” “Naturalism” and “realism” often used interchangeably, which can cause some confusion. Thomas Postlewait, “Realism and Reality,” in The Oxford Companion of Theatre and Performance, ed. Dennis Kennedy (OUP, 2003). “Naturalist drama, such as Hauptmann's The Weavers (1892) and Gorky's The Lower Depths (1902), tended to represent the economic and environmental forces that controlled, even determined, the characters' behaviour. By contrast, realistic drama, such as Ibsen's Hedda Gabler (1890) and Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard (1904), located the suffering of the characters in their social values and psychological selfdeceptions, though a strain of economic, social, and hereditary determinism may operate in these plays as well.” The “well-made” play Pioneered by French playwright Eugene Scribe and perfected by Victorien Sardou. •Play centres around a secret or dilemma known only to one or two characters (and the audience). •Tripartite structure: 1) initial exposition 2) Characters experience discovery, intrigue, evasions, ups and downs in fortunes 3) the scène à faire (the “obligatory scene”) in which the characters confront each other. • The chains of events and the denouement must all be logical and plausible. The overall structure should be repeated in each act. Such plays were much derided for their superficiality and formulaic nature. They privileged structure over content. George Bernard Shaw dismissed them as “Sardoodledum”. The late nineteenth-century realists – Ibsen not least – soundly rejected the “wellmade” play. They wanted to confront social and political problems and favoured ambiguity to neatness and formula BUT … the tight structure of works like Hedda Gabler bear the trace of the “wellmade” play even as they turn away from its values. Ibsen EARLY CAREER 1835 Born in Skien, Norway. 1849 Drafts first play, Catiline, while working as an apothecary's assistant in Grimstad. 1850 Moves to Christiania, the capital, to study. Writes The Warrior's Barrow, which is performed by the Christiania Theatre. 1851 Gives up studies to become assistant director at the newly founded National Theatre in Bergen. During six years there he learns effective use of stage space and continues to write plays in the national romantic tradition, including Lady Inger of Ostrat (1855) and The Feast at Solhaug (1856). 1857 Becomes artistic director of the Norwegian Theatre in Christiania. A period of despair and poverty ensues, despite marriage in 1852 to Suzannah Thoresen. In 1862 his theatre goes bankrupt. Writes a light-hearted satire, Love's Comedy (1862), and the last of his national romantic plays, The Pretenders (1863). 1864 Leaves Norway for Rome, with the aid of a state grant. His exile will last 27 years. His creative energies renewed, he writes two verse plays that bring international recognition: Brand (1866) and Peer Gynt (1867). 1868 Moves to Dresden where he completes his long philosophical play, Emperor and Galilean (1873). Ibsen REALISM In the late 1870s embarks on a new phase in his playwriting: now seeks to address contemporary social issues in works that cause considerable outrage. • • • The Pillars of Society (1877): a critique of capitalist entrepreneurs. A Doll's House (1879) and Ghosts (1881): dissect middleclass marriage. An Enemy of the People (1882): ironic portrait of an individual who is ostracized for speaking the truth. These works reenergize the “problem play” (as practised in England by Henry Arthur Jones and A. W. Pinero), but Ibsen avoids the contrivance and preachiness that often characterizes it. Rather, Ibsen’s plays focus in an intense and relentless fashion on a highly particularized situation and set of characters. It is only through the particular that general crisis (ideology, class, gender) is glimpsed. Ibsen … AND SYMBOLISM The Wild Duck (1884) marks the beginning of Ibsen’s interest in symbolist techniques, a move that sits in tension with his realism. Other plays of this period include Rosmersholm (1886), The Lady from the Sea (1888), and Hedda Gabler (1891) - the last play Ibsen wrote during his exile. FINAL PLAYS Returns to Norway in 1891 The Master Builder (1892), John Gabriel Borkman (1896), and When We Dead Awaken (1899) explore the tension between life and art, creative vocation and happiness. These plays mix realism with elements of expressionism. In 1900 Ibsen suffers the first of two strokes, which leave him unable to write. He dies in 1906. Ibsen in England Popularity and critical reputation of Ibsen in England largely due to three men: Edmund Gosse • Critic and man of letters. • Much his critical work in the 1870s was devoted to Scandinavian literature and his reviews first introduced Henrik Ibsen's name to England. William Archer •Scottish critic, journalist, and translator. •The first to introduce Ibsen’s plays to the British public: The Pillars of Society in 1880; A Doll's House in 1889; Ghosts in 1891. •Championed new playwriting and criticized the over-valuation of older works. •Translated all of Ibsen’s works into English, publishing them in 11 volumes in 1906-8. Max Beerbohm satire of Archer’s adulation of Ibsen (The Poets’ Corner, 1904) Ibsen in England George Bernard Shaw •Dramatist and critic. Wrote The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891; expanded 1913). •This aimed “to distil the quintessence of Ibsen’s message to his age” (15), though GBS concluded that “its quintessence is that there is no formula” (125). “Ibsen supplies the want left by Shakespear. He gives us not only ourselves, but ourselves in our own situations. The things that happen to his stage figures are things that happen to us. One consequence is that his plays are much more important to us than Shakespear's. Another is that they are capable both of hurting us cruelly and of filling us with excited hopes of escape from idealistic tyrannies, and with visions of intenser life in the future.” (202) Hedda Gabler: a Greek tragedy? Published in 1890 and first performed in January 1891 at the Königliches ResidenzTheater , Munich. Its English premiere followed in April the same year. •Observes the three Aristotelian unities of time, action, and place. •The plot revolves around Hedda’s harmartia. She is, psychologically, a flawed character. •Her doom is inevitable from the opening of the play, at least in retrospect. •She experiences anagnorisis. HEDDA [to Brack]: I’m still in your power. At your disposal. A slave. [She gets up impatiently.] I won’t have it. I won’t. (p. 294) •The play closes with her death, which notably occurs offstage. But Ibsen’s is a fiercely secular drama. There is no God, only the impossibly powerful force of social convention. The Gods are replaced by the ideologies of class and gender. In Hedda Gabler the central agon is not between the free will and Fate but rather between the individual – struggling for freedom – and society. The structure of Hedda Gabler Four acts, each shorter than the last: sense of increasing acceleration towards the inevitable catastrophe. Each act a self-contained unit. Act 1: The Tesmans return from their honeymoon •Various details about the Tesmans marriage and aspirations are revealed: Hedda is pregnant, Jørgen expects a professorship, Ejlert Løvborg has returned and published an important book with the help of Thea Elvsted. •The act reveals just how out-of-place Hedda is within the marriage and house. Act 2: Hedda’s relationship with Brack and Løvborg •Hedda’s determination to control the men around her – first Brack, with whom she flirts, and then Løvborg - is shown. •She goads Løvborg into drinking and attending Brack’s party, wllfully destroying the reformation brought about by Thea. Act 3: The aftermath of the party •The loss of Løvborg’s manuscript. Hedda’s burning of it. •Hedda’s destruction of it. Act 4: Death •The ugly suicide of Løvborg reported. Thea and Jørgen unite to reconstruct the manuscript. •Hedda is ensnared by Brack and no longer needed by Jørgen. She kills herself. The structure of Hedda Gabler Four acts, each shorter than the last: sense of increasing acceleration towards the inevitable catastrophe. Each act a self-contained unit. Act 1: The Tesmans return from their honeymoon Hedda seeks control. Act 2: Hedda’s relationship with Brack and Løvborg Hedda gains control. Act 3: The aftermath of the party Hedda exerts control through acts of creation (setting up Løvborg’s suicide) and destruction (the burning of the ms). Act 4: Death Hedda comes to recognize that the more she has sort control and freedom the more she has ensnared herself. The realism of Hedda Gabler: scenography The opening stage direction: A smart, spacious living room, stylishly decorated in dark colours. Upstage, a wide double-doorway, with its curtains drawn back, leads leads into a smaller room, decorated in the same style. Right, exit to the hall. Opposite left, through a glass screen door curtains also drawn back, can be seen part of a raised verandah and a garden. Centre stage, dining chairs and an oval table covered with a cloth. Downstage right, against the wall, a dark tiled stove, a wing chair, an upholstered footstool and two stools. Upstage right, a corner seat and a small table. Downstage left, a little out from the wall, a sofa. Upstage of the screen door, a piano. On either side of the main double-doorway, whatnots displaying artefacts of terracotta and majolica. In the inner room can be seen a sofa, a table and two chairs. Over the sofa hangs the portrait of a handsome elderly man in general's uniform. Over the table, a hanging lamp with a pearled glass shade. All round the main room are vases and glass containers full of cut flowers; other bouquets lie on the tables. Thick carpets in both rooms. Sunlight streams in through the screen door. (Act 1; p. 165) The realism of Hedda Gabler The opening stage direction: •Remarkable precision and detail: carpets, doors, furniture, ornaments, flowers. •This room – or rooms – remains the setting for the entire play. It is the only space the audience see. •Immediately clarifies the dramas concerns: domesticity, privacy, bourgeois taste and aspiration. Inside and outside In Greek drama we are never taken inside (though we may see into an interior space when the doors of the skene open). Everything is played out in a public space, in fictional as well as actual terms. Ibsen’s is a drama of privacy. We are never taken outside (though we glimpse exterior space through the glass doors). The audience, like the characters, are trapped within the claustrophobic space of the bourgeois home. The realism of Hedda Gabler: speech As in all of Ibsen’s major plays, characters speak in a colloquial language. Their words have an everyday economy. BRACK: Well, Mrs Tesman. It’s time. HEDDA: Yes, time. LØVBORG (getting up): Time for me as well. MRS ELVSTED (low, beseeching): Eijlert, don’t. HEDDA (pinching her arm): They can’t hear you. MRS ELVSTED (a little shriek): Ow. (Act 2; p. 219) •Ibsen pays special attention to modes of address. Brack privately calls Hedda “Hedda Gabler” but here addresses her as a married woman. •Hedda addresses her husband as Jørgen (rather than Tesman) only a few times – when she wants something. The symbolism of Hedda Gabler Hedda Gabler written during a period when Ibsen was integrating realism with some of the techniques of symbolism. The set and carefully arranged stage space take on symbolic value: •The doors suggest “fresh sir” and escape. •The packed room is oppressive; Hedda finds the flowers “dreadful” in their overabundance (173). •Hedda feels that the “old piano” doesn’t “look right here”. It’s out of place, like Hedda herself. •The portrait of General Gabler: a constant reminder that Hedda Tesman was Hedda Gabler – and of the violence that is Hedda’s inheritance (literally, with the guns). Other important motifs: •The manuscript as a “child”. •The guns are an obvious phallic symbol. The characters themselves think and sometimes speak in symbolic terms. The symbolism of Hedda Gabler Simple words accrue symbolic charge: BRACK: Well, Mrs Tesman. It’s time. HEDDA: Yes, time. LØVBORG (getting up): Time for me as well. MRS ELVSTED (low, beseeching): Eijlert, don’t. HEDDA (pinching her arm): They can’t hear you. MRS ELVSTED (a little shriek): Ow. (Act 2; p. 219) The language here is colloquial, yet the word “time” – spoken three times by three different characters and given special emphasis by Hedda – marks this word as one of the key themes of the play. The everyday and the symbolic overlie one another. Hedda Gabler: women Ibsen often regarded as a feminist playwright. Hedda struggles against the constraints of the respectable femininity – and the roles of wife and mother – that she is expected to embody. She yearns for the freedom and control that the men around her seem to possess: LØVBORG: … When I confessed, didn’t you want to absolve me, to wash away my sins? HEDDA: Not exactly. LØVBORG: What, then? HEDDA: You really don’t know? A young girl … without anybody knowing … her chance … LØVBORG: Chance? HEDDA: To glimpse a world that … LØVBORG: That – ? HEDDA: That she’d no business to know existed. (Act 2; pp. 213-4) Hedda Gabler: women Ibsen often regarded as a feminist playwright. Hedda struggles against the constraints of the respectable femininity – and the roles of wife and mother – that she is expected to embody. She yearns for the freedom and control that the men around her seem to possess: BRACK: So, gentleman, the carnival begins! I hope it’ll be … ‘jolly’, as a certain charming lady puts it. HEDDA: I wish a certain charming lady could be there, invisible – (Act 2, p. 220) As she tells Thea: “For once in my life, I want to control another human being’s fate.” (Act 2; p. 221) Hedda Gabler: women Hedda vs Nora Many of Ibsen’s female characters are driven by this desire to overturn the world of sexual inequality and access realms of experience and power denied to women. But Hedda is different from Nora Helmer, the heroine of A Doll’s House. Nora: leaves her husband and children once she comes to recognize that her marriage has been a dangerous fantasy. Hedda: a “coward” (Act 2; p. 214) who behaves maliciously to every character on stage in a desperate attempt to manipulate them: she insults her husband’s aunt, drives an reformed alcoholic to drink, bullies Thea, incites suicide, and burns the manuscript. Hedda is a character of unresolved contradictions. She is cold and detached and yet passionate and sexually aware. Many of her actions go partially or wholly unexplained. There is little clarity to her motives or coherence to her actions. Ibsen presents a psychological portrait that is unsympathetic and complex. Hedda Gabler: the female Hamlet? Notable recent Heddas: • • • • • Cate Blanchett (Brooklyn Academy of Music, NY, 2005) Eve Best (Almeida, 2006) Mary-Louise Parker (American Airlines Theatre, NY, 2009) Rosamund Pike (Theatre Royal, Bath, 2010) Sheridan Smith (Old Vic, 2012) Other actresses to play the role include: • Dianna Rigg • Maggie Smith • Janet Suzman • Ingrid Bergman • Juliet Stevenson • Annette Bening • Kate Mulgrew • Kelly McGillis • Harriet Walter Hedda Gabler: class Above all, Ibsen’s plays are driven by a critique of bourgeois ideology. Claims to be founded on the sanctity of freedom, social and political. But what was dynamic and revolutionary at the beginning of the nineteenth century (the era of a French Revolution) had for Ibsen become sterile and repressive. The paradox: the bourgeoisie have betrayed their own values. They purport to cherish freedom but fear and repress any force or individual that might threaten the status quo. Jørgen: the champion of mediocrity; respectability and position (the professorship) more important than intellectual accomplishment. Brack: a judge, who is supposed to stand up for law and freedom but who works to subvert justice and use his position to engage in sexual blackmail. Bourgeois values of freedom, endeavour, intellectual progress are all inverted by precisely those who claim to embody them. Hedda Gabler: class Ejlert Løvborg: •An outcast because he refuses to conform to the Apollonian mask of the middle class (Hedda would have him be Dionysiac). •Brack and Tesman drink too much and misbehave but do so behind closed doors. Immorality is acceptable provided it doesn’t show itself publically. This is Løvborg’s mistake. Hedda encourages Løvborg to drink but so too do Jørgen and Brack. All seem to wish his destruction, though from very different motives. Hedda is caught between a compulsion to rebel against the dictates of this society and an equally strong need to obey them. She admit to Løvborg that she’s afraid of “scandal” (Act 2; p. 214) The conflict that destroys Hedda is the tension that inheres within bourgeois society itself: the imperatives of autonomy and beauty are irreconcilable with those of respectability and wealth. Bourgeois ideology simultaneously tells the individual to stand out – to be more – and to fit in, to detest difference. Ibsen’s pessimism? Løvborg’s book claims to be able to know the future, to plot its “Cultural Determinants” and “Cultural Directions” (Act 2; p. 207). Such a view is predicated on the notion that no individual can alter the course of human history. Does Ibsen subscribe to such cultural determinism? •The play suggests no escape route from the overwhelming force of conformism. Does it present characters that have any real free will? •Like Oedipus, Hedda seeks to seize agency – to change destiny – but succeeds only in ensuring its enactment. “The tragedy of Hedda in real life is not that she commits suicide but that she continues to live. The tragedy of modern life is that nothing happens and that the resultant dullness does not kill. In Ibsen’s works we find the old traditions and the new conditions struggling in the same play … Not only the tradition of the catastrophe unsuitable to modern studies of life: the tradition of the ending, happy of the reverse, is equally unworkable.” -George Bernard Shaw