Chapter 26: Real Property

advertisement

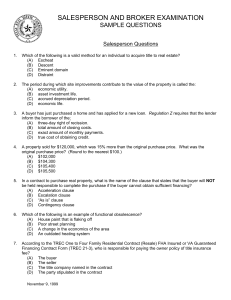

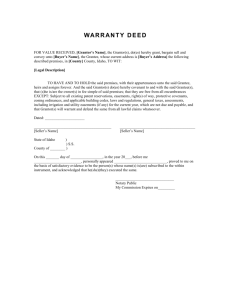

Chapter 26: Real Property Joey Buterbaugh and John Sturgeon—Edited Shelby Pieper and Nic Schworer I. Distinction between real and personal property Real property refers to not only land but also property attached as a permanent structure to the land. Buildings constructed on a tract of land are thus considered part of the real property, and any owner of land also owns the air above it, the soil below the surface, and any vegetation. The key distinction between real and personal property is that real property is immovable or attached to something immovable. This distinction carries importance because there is a separate set of rules and regulations that govern transactions of real property. It is also important to note that the character of property is not always fixed. It is possible for personal property to be installed or attached to real property, thus becoming part of the real property. Any property that undergoes this conversion is known as a fixture. II. Ownership Interests In many situations, a piece of real property is owned by one individual, and that person also possesses all the rights that come along with land ownership. However, it is often the case that these rights of ownership are spread among multiple parties, and this distinction is important because it affects how each person can legally use the land. A. Fee Simple Perhaps the simplest of the possible interests a person may have in land is known as fee simple absolute. This refers to the common notion of owning land in full, and such an owner also carries the right to possess and utilize the property for an indefinite period of time. One who owns real property in fee simple absolute also has the power to transfer the land during his or her life or at death, and can grant rights to others without giving up control of the land. Examples of such rights given would be allowing a mortgage on the property, making the property available to rent, and so on. B. Fee Simple Defeasible Chapter 26 Real Property Page 1 A second type of ownership interest in real property is fee simple defeasible. An owner in fee simple defeasible means that ownership is conditional upon the occurrence or non-occurrence of a future event. An example of this would be a father transferring land to a son on the condition that the property not be used for commercial purposes. If the son were to break this condition, the father could take legal action and reclaim the land. This type of ownership is also commonly referred to as fee simple determinable. C. Life Estate The third and final type of ownership a person can carry in real property is called a life estate. This type of interest is granted to a person to use the property during his lifetime or the lifetime of another person. Upon death of the person specified, the property either reverts back to its original owner or passes to a third designated party as specified by the property’s title. In this situation it is also important to note that a person who has a life estate in real property is prohibited from taking actions that would permanently damage the property and thus hinder its use by future parties. Ownership Interest Examples: 1. “Michael to Kobe and his heirs” – Michael grants Kobe a fee simple absolute. Michael has nothing, and land is fully passed to Kobe. 2. “Kobe to LeBron and his heirs, as long as the property is used for basketball purposes.” – Kobe has granted LeBron a fee simple defeasible, and Kobe retains the possibility of getting the land back in the future if the condition is broken. 3. “Michael to Kobe for life” – Michael grants a life estate to Kobe, and retains a fee simple absolute in the property after Kobe’s death. 4. “Michael to Kobe for life, then to LeBron and his heirs” – Michael has granted Kobe a life estate, and LeBron gets a remainder interest in fee simple absolute. In this case Michael gets nothing because he’s specified who gets the property after Kobe dies. III. Concurrent Ownership of Real Property The concepts above describe a single person’s ownership interests in real property; however, it Chapter 26 Real Property Page 2 is also common for two or more people to share ownership. In these cases, the co-owners do not have separate rights in the property and do not own distinct portions of the land, but rather each has a share in the whole property. A. Tenancy in Common One of the most prevalent forms of co-ownership is a tenancy in common. Here, owners have equal rights to possess and use the property, but they do not have to possess equal ownership percentages. For example, one tenant could own 75% of the property, another own 20%, and a third own 5%. Regardless of the percentages of ownership, each owner has equal rights to use the property, but the percentages do dictate how income generated from the property is distributed. In the above example, if the piece of land generated $100,000 in rent each year, the first owner would receive $75,000, the second would get $20,000, and the third $5,000. In the same manner, owners must pay their proportion of property taxes and other costs to maintain the property. A tenant in common may pass on his or her ownership interest freely during life and at death via a will. If no will has been made, the property passes automatically to the decedent’s heirs, who in turn become owner(s) by tenancy in common. A tenancy in common may also be severed by the co-owners agreeing to divide up the property. If they are unable to reach agreement on exactly how this division should be accomplished, the owners can petition a court to divide the property if possible. If the court cannot feasibly divide the property, it may sell the land and distribute the proceeds according to each owner’s percentage interest. B. Joint Tenancy Another option for co-ownership in real property is a joint tenancy. When the ownership document clearly specifies two or more owners possess property by joint tenancy, each owner will receive equal interests. As with tenancy in common, each owner has the right to use the property, receive his or share of rents, and to partition if desired. However, in a joint tenancy, owners have a right of survivorship, which means that if any owner dies, his or her share automatically passes to the remaining owner(s). For example, suppose that Payton and Marvin own Colt Ranch as joint tenants. If Payton dies, his ownership interest passes to Marvin even if such a transfer is not specified in Payton’s will. Further, if Payton’s will specifies his land should go to a third party, that part of the will is deemed ineffective and the land still passes to Marvin. During one’s life, a co-owner in joint tenancy is still permitted to sell or give interest in the land to a third party. If this occurs, the joint tenancy is broken and a tenancy in common is created with respect to the percentage interest transferred. Thus it is possible for tenants in common and joint tenants to simultaneously own the same property. For example, suppose Able, Baker, and Charlene are joint tenants—each with a one third interest. While Able is still alive, Able (without permission of the others) could Chapter 26 Real sellProperty or give his interest to Dale. Since joint tenancy is not assumed, Dale is a tenantPage 3 in common in relation to Baker and Charlene (though Baker and Charlene are still joint tenants between themselves). If Baker died, Charlene would own 2/3 of the property and Dale and Charlene would be tenants in common. Dale would own 1/3. If the document of title for the land does not clearly specify ownership by joint tenancy, a court may step in and decide whether the owners acquired the property through tenancy in common or as joint tenants. For joint tenancy to be granted, the following requirements must be met. 1. Unity of time – ownership interests of joint tenants must arise at the same period in time. 2. Unity of interest – all joint tenants must own exactly the same percentage interest. 3. Unity of title – ownership interests must have been created by the same document. 4. Unity of possession – each person possessing an ownership interest must have the right to possess the property. 5. Use of requisite language – the document conveying ownership – often a deed – must contain specific language that owners are joint tenants. If the document is silent on the type of ownership, it is assumed that the owners are tenants in common. C. Tenancy by Entirety Many, but not all states, also permit married couples to own property under tenancy by entirety. Again there is the right of survivorship and a will is irrelevant. This type of ownership is essentially a special form of joint tenancy with the additional requirement that there exist only two owners, and they are married. The distinguishing feature is that a tenancy by entirety cannot be broken without the consent of both owners. This means that a creditor of one tenant cannot obtain an interest in the wife’s share of the property without consent of the husband. A tenancy by entirety can be severed by divorce, at which point it converts to a tenancy in common. Also, this means that any sale of the property must be agreed upon by both owners. Chapter 26 Real Property Page 4 IV. Transfer of Ownership Real property may be acquired and transferred between individuals in many ways, including through a will, eminent domain, adverse possession, or the use of a deed. A. Transfer by Will Transferring property by means of a will is relatively straightforward. An owner (grantor) of real property has the ability to designate, through a will, a future owner of the property upon death of the grantor. If an owner does not create a will during life, the property passes to his heirs as determined by state law. B. Eminent Domain The government has a unique right to acquire land through eminent domain. The Fifth Amendment states that from no person “shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” This clause effectively gives the government the right to take control of real property for roadways, dams, public housing, and any other public use deemed necessary for the land. The government also has the power to delegate eminent domain to private corporations that have needs for specific tracts of land to conduct business. Common examples of companies that obtain this power from the government are railroads and utilities. Eminent domain does not require the consent of the previous owner and thus often leads to problems in practice. The first problem is determining exactly when the power can be properly exercised. It is fairly straight-forward when the government obtains property directly for use in a public project, but difficulties arise when the property is obtained for private development. In addition, a second problem encountered is through the concept of “just compensation.” The previous owner of the property is entitled to receive “fair market value” for the property, but this is sometimes difficult to define, and often it does not adequately cover the owner’s loss. For example, just compensation may not account for an individual’s emotional attachment to a specific house that has been in the family for generations. Finally, a third problem with eminent domain is determining when it has actually taken place. In many cases the government takes a formal action to obtain property, but in other situations, it is much more difficult to tell whether a government action has triggered eminent domain. Take, for example, a public project to construct a large dam. It is not uncommon for these type of projects to result in flooding in adjacent tracts of land, and some argue that this triggers the owner’s right to receive just compensation from the government. These inverse condemnation cases are generally decided by the courts on an individual basis. C. Adverse Possession Chapter 26 Real Property Page 5 Just as the government can obtain possession of land without the owner’s consent, so too can any party through adverse possession. This occurs when someone wrongfully possesses land for a specific period of time (as determined by each state) and the rightful owner takes no steps to regain possession. After the statute of limitations has passed, the party who has used the property is said to acquire title through adverse possession. The five requirements for obtaining property though adverse possession are as follows: 1. The possession must be open. 2. The act of possession must be actual. 3. The property must be possessed continuously throughout the statute of limitations (10-30 years depending on state law).This requirement may be met by multiple successive possessors as long as there are no gaps in time. 4. The possession must be exclusive. 5. Possession must be hostile or adverse to the actual owner’s rights D. Deeds One final way to transfer ownership of real property is through the use of a deed. A deed is a legal instrument used to transfer rights in real property. The rights are transferred from a grantor to another party, the grantee. Unlike some of the methods of transfer described above, deeds require mutual agreement of both parties involved. The first and most basic type of deed is the quitclaim deed. The quitclaim deed is given when the grantor disclaims any interest he or she may have in the property, and does not warrant that his or her claim in the property is valid. In this situation, the grantee does not have the ability to take legal action against the grantor if it is subsequently discovered that good title has not been obtained through the deed. This type of deed is often used to settle land disputes. To solve this problem, warranty deeds are often used in place of quitclaim deeds. Unlike a quitclaim deed, in a warranty deed the grantor makes a claim and guarantees title in the property transferred. There are two kinds of warranty deeds: In a general warranty deed, the grantor guarantees that he or she has good title in the property, and this guarantee is extended back to the origin of the property. With a special warranty deed, the grantor only guarantees against claims which occurred after the grantor obtained possession of the property. This type of warranty deed is more specific and gives the grantee less security in the grantor’s good title in the property. This is sometimes referred to as a Chapter 26 Real Property Page 6 “bargain and sale” deed. Although the delivery of a deed from grantor to grantee conveys title of the property, for the grantee’s sake it is wise to also record the deed with the applicable government office. By recording a deed with the applicable government office, the grantee has signaled to others via a central location of his or her rights in the property. In these locations, which are usually county clerk’s offices, all information on recorded deeds is available to the public. Although this process provides some stability in property ownership, it cannot guarantee those rights. V. Buying Property The following steps are generally involved in the transfer of real estate by sale: 1. Contracting with a real estate broker (to find a buyer), 2. Creating the contract of sale, 3. Satisfying other requirements of the sale, (acquiring financing, a survey, title insurance, etc) 4. Closing the sale, and 5. Recording the deed. These steps are discussed in more detail below. A. Contracts Two contracts involved with the transfer of real property by sale are 1) the contract between the seller and real estate broker and 2) the contract between the seller and the buyer. It is not required Chapter 26 Real Property Page 7 that seller use a real estate broker, but this is often the case. Thus, the seller will contract with the broker, which allows him or her to act as the seller’s agent in seeking a buyer. The following are types of listing contracts between a seller and a broker: 1. Open listing – In this case, the broker receives a nonexclusive right to sell the property, meaning that other parties (including the seller) are still entitled to find a buyer for the property and the broker will only receive commission if he finds a buyer first. 2. Exclusive agency listing – The broker may receive a commission if he or another agent (broker) finds a buyer. The seller can still find a buyer himself, however, and not be obligated to pay a commission. 3. Exclusive right to sell – The broker has an exclusive right to sell the property for a specified period of time, and will receive a commission no matter who (including the seller) finds a buyer. Other general terms specified in the contract may be the length of the listing period, the seller’s terms to sell, and conditions of the broker’s commission (terms and amount). The contract between the seller and the buyer (contract of sale) is within the statute of frauds and must be in writing. It will specify the parties and the property involved, the purchase price, the type of deed to be received by the buyer, and other items to be sold. Sale closing is often contingent upon the buyer obtaining financing at a certain interest rate, the property passing a termite inspection, and the seller obtaining survey and title insurance. B. Title Insurance In a sale of real estate, the buyer is actually purchasing the seller’s title in the property (ownership interests). The buyer wants to make sure that the seller actually has good title to the property so he/she does not pay for something with no value. The most common way to gain this assurance is through title insurance. The buyer is referred to as an “insured grantee” in this situation, and will be reimbursed by the insurer if the title proves defective, or if there are litigation costs and the buyer has to go to court in a title dispute. A lender may also require that a separate policy be obtained for their protection. C. Closing The closing of a real property transaction primarily involves the payment of the purchase price and the transfer of the deed. Although the deed formally conveys title from the seller (grantor) to the buyer (grantee), the deed should be recorded immediately. This protects the buyer from other third parties who may have interests in the property. D. Registration of Deed Chapter 26 Real Property Page 8 The registration of deed (also known as “recording”) is governed in each individual state by a recording statute that establishes the system for recording any transaction affecting real property ownership. As described above, the primary purpose of recording the deed is to provide the public with notice of the buyer’s (grantee) interest in the property. The recording statutes assign priority to competing claimants to rights in real property (in the event that the property is deeded to more than one person who has given value). The following are the three most common types of recording statutes set up by a state: Race Statutes – This is the most uncommon form, but it gives priority to whoever recorded their deed to the property first. Notice Statutes – This system gives priority to the later grantee if he acquires his interest without notice of the earlier grantee’s interest (i.e. the earlier grantee did not record his deed before the later grantee acquired an interest and did not know). Race-Notice Statutes – This system gives priority to the later grantee if he acquires his interest without notice (either real or constructive) of the earlier grantee’s interest and he records his deed first. Missouri uses this rule. VI. Mortgages When real estate is being transferred, mortgages are often involved. A mortgage is essentially a mechanism for using real estate as collateral for a debt obligation. The owner (mortgagor) uses the real property to obtain funds from the creditor (mortgagee). Often in the sale of real estate, the seller will still have a mortgage on the property, and the buyer may purchase property subject to a mortgage or he or she may assume the mortgage. A. Buying Subject to a Mortgage If the buyer purchases the property subject to a mortgage, he or she will not become liable for payment of the mortgage debt, but rather the seller (original mortgagor) will still be liable. However, if the original mortgagor defaults on the debt, the property can still be foreclosed and sold to satisfy the debt. The buyer will not be liable for any deficiency. B. Assuming a Mortgage When the buyer assumes the mortgage, he or she essentially agrees to takeover the existing mortgage on the property. A buyer might wish to assume the mortgage on a property if the original mortgagor had a better interest rate than the buyer could obtain individually. The buyer will become personally liable for the debt and any deficiency in the case of default and foreclosure. The seller will also remain secondarily liable on the debt (as a surety) – and will have to pay if the buyer does not. The assumption of a mortgage can be prohibited with the inclusion of a “due on sale” clause. However, if the bank agrees to the mortgage assumption, then the seller can be released from obligation - this is called a novation. A novation requires that all three parties agree to it: the bank, the seller, and the buyer. Chapter 26 Real Property Page 9 C. Registering a Mortgage Lastly, the mortgagee will want to record the mortgage. The mortgage is generally recorded with the recorder of deeds in the county where the property is located. The purpose of recording the mortgage is to give notice to any other parties who might wish to take an interest in the property. In the case where there are two or more parties who have an interest in the property, recording the mortgage plays a major role in determining who has priority. This priority is established by the same recording statutes (per state law) that affect transferring deeds and other transactions affecting real property ownership. The three general types of recording statutes (race, notice, and race-notice) are discussed above. VII. Easements An easement is either the right to make certain use of another person’s property, or the right to prevent someone else from making certain use of their own property. The former is called an affirmative easement, and the latter is called a negative easement. An example of an affirmative easement would be an arrangement where one party can run power lines through another person’s property. An example of a negative easement would be where a resident in a neighborhood would be prevented from using their land to raise farm animals. There are several ways that an easement may be obtained. The three discussed here are easement by grant, necessity, and prescription. A. Easement By Grant: An easement by grant is created when the owner of the property expressly provides an easement to someone else and retains ownership of the property (i.e. the easement is sold or given to another). This is done through a deed of easement, which is required to be in writing and signed by the person granting the easement. B. Easement By Necessity: An easement by necessity is generally created when property is subdivided and sold, and one of the new owners can only access his/her property by going through another’s property. For instance, assume that Joe owns an entire plot of land, and he sells the eastern half to John and the western half to Steve. If the only public access to the land runs across the eastern border owned by John, and Steve must then cross John’s property to reach his own on the western side, then Steve is entitled to an easement by necessity to cross John’s land and access his own land. Chapter 26 Real Property Page 10 C. Easement By Prescription: An easement by prescription is created under the following circumstances: one person uses another’s land openly, continuously, and in a manner against the rights of the owner for a specified period of time (time period is specified by state statute). This implies that the owner has not given permission for this use of the land. If the owner does not take action to stop the use of the property within the time period, then they will lose the right to stop the use – they are presumed to be on notice that someone else is acting as if they have those rights to the property. The owner may also be using the land (which stops the trespasser from gaining ownership)—thus possession is not exclusive. For example, suppose that in a given state, the time period for an easement by prescription is 10 years. Jimbo has been cultivating and maintaining a garden on Steve’s property without his permission, openly and continuously, for the last 11 years. If Steve has made no action to stop Jimbo’s operation of the garden, then Jimbo will be entitled to keep using the property with an easement by prescription. This easement will continue even if the property is sold. VIII. License to Enter Property Temporarily A license is generally more informal than an easement, and it represents the temporary right to enter someone else’s land for a specific purpose. The landowner (licensor) is essentially giving someone else (licensee) permission to enter his/her property. This is not a true interest in the land, and the licensor can generally revoke the license. The situations where the license may not be revocable are when the licensee has interest in property located on the land, or when the licensee has given value for the license. IX. Profit-Right to Oil/Mineral Rights Profits are generally pertinent to oil or mineral rights, and are often governed by the same rules applicable to easements. A profit is the right to enter another’s property and extract some part or product of the land. In fact, sometimes profits are referred to as easements with a profit. Chapter 26 Real Property Page 11