The City of Santa Cruz 2014-2023 Housing Element is designed to

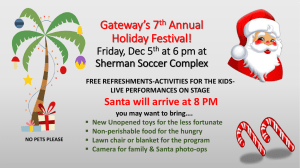

advertisement