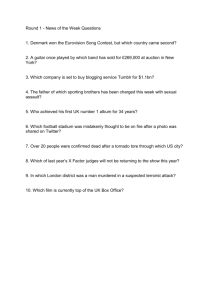

Protest Singer/Song List

Politics and Protest

Protest Singer/Song List

Whether its old classics passed down through generations or the scream of angry young voices, protest has always been at the centre of rock'n'roll. But are there any songs we've missed that you'd like to protest about?

Me and Giuliani Down by the Schoolyard (A True Story) !!! 2003

Rudolph Giuliani’s tenure as mayor saw New York nightlife all but stamped out; his taskforce would close down venues without a dance license if people so much as tapped their foot. When the bar Nic

Offer was working at fell victim to Giuliani’s clampdown, the !!! front man was driven to write this nineminute punk-funk epic, which attempts to start a dance floor insurrection.

Another World Antony and the Johnsons 2008

There’s perhaps no other current artist who could pull off an apocalyptic lament that sounds like a gentle hymn. This lead track from last year’s EP and highlight of new album The Crying Light is a plea for escape from a world “nearly gone” through war and ecological disaster. That unique, soulful voice sounds utterly bereft, as it waves us a resigned goodbye: “I’ll miss the things that grow/ I’m gonna miss you all.”

Windowsill Arcade Fire 2007

Arcade Fire’s second album, Neon Bible, was full of bad vibrations. On Windowsill, Win Butler turns refusenik, driving salesmen from his door, repudiating consumerism and watching the flood waters rise.

But even with Armageddon nigh, Windowsill feels like a victory, as voices and brass mass to a climax.

Conclusion? With enough instruments, we might just make it. It’s a compelling argument.

(What Did I Do To Be So) Black And Blue Louis Armstrong 1929

Friend to the world he might have been, but Pops didn’t hide behind that smile. Listen to this 1929 performance of a Fats Waller number, on which he sings “I’m white inside but that don’t help my case,” and “My only sin is in my skin.” Little wonder that the protagonist of Ralph Ellison’s classic novel Invisible

Man dreamt of listening to five versions of the song simultaneously.

Stand Up for Judas Roy Bailey 1979

Leon Rosselson has been Britain’s most consistently savage and articulate political songwriter for four decades, but none of his songs have put as many noses out of joint as this epic, rip-roaring deconstruction of popular Christian perception of the Gospels. Part inspired by Hyam Maccoby’s book

Revolution in Judaea, Rosselson’s detailed contention that Judas was a heroic political revolutionary subverting the Roman occupation while Jesus was effectively a passive collaborator comes with a blinding chorus fully utilized by Bailey’s impassioned delivery.

A Day in the Life of a Tree The Beach Boys 1971

By this point in his career, it was said of Brian Wilson that he was crazy. But this number, from the album

Surf’s Up, co-written and sung by Jack Rieley, made up in anguished sentiment what it risked in eccentricity. And now that we’re all hip to global warming, how nuts do the lines “But now my branches suffer/ And my leaves don’t offer/ Poetry to men of song” sound exactly?

I Was Born This Way Carl Bean 1977

“Say it loud,” the lyrics might have read, “I’m out and I’m proud.” This disco stormer, the genre’s first gay anthem, was given its definitive treatment in this cover of Valentino’s 1975 original. “I feeeeeeeel good! I feeeeeeeel good!” sang Bean, his gospel roots never more in evidence. It’s not the most widely feted Motown single, but it remains one of the most inspirational.

Stand Down Margaret The Beat 1980

A highlight of the Beat’s debut album, I Just Can’t Stop It, this unambivalent demand feels like a brash cousin of Ghost Town, the Specials’ more complex, downbeat song of social protest. Released just 12 months after Thatcher came to power, the Brummie ska outfit had already seen straight through the new regime: “I see no chance of your bright new tomorrow/ Our lives seem petty in your cold grey hands.”

I Am the Walrus The Beatles 1967

With its “semolina pilchard climbing up the Eiffel Tower”, this anguished howl is easily dismissed as a piece of nonsense – and was written by John Lennon as a riposte to the news that a teacher at his old school was now analyzing the Beatles’ lyrics in class. But this masterpiece saw him vent his spleen on establishment culture writ large, and few bands ever sounded quite so menacingly psychedelic. (Just don’t believe that the walrus really was Paul.)

Revolution The Beatles 1968

On this wild, distorted B-side to Hey Jude, John Lennon insisted that, if 1968’s revolutionaries wanted destruction, they could “count me out”. On the slower, quieter version (Revolution 1) on the White

Album, the line is “count me in”. Lennon’s honest confusion drew much flak from those who wanted him to be a political figurehead. The screeching, unsettling production was Lennon’s riposte to his fellow

Beatles’ refusal to release Revolution 1 as a single.

War Pigs Black Sabbath 1971

Long before Ozzy became a clown and heavy metal a joke, Black Sabbath’s War Pigs was like a

Hieronymus Bosch painting come to life. Ripe with rot and rich with musical detail, this seminal outpouring of pacifism noir brought Birmingham’s infamous hippie-haters intriguingly close to their flower-powered, anti-Vietnam war peers. But there is no mistaking the animosity in Bill Ward’s apocalyptic hoof beats, or Tony Iommi’s acidulated guitar.

Melting Pot Blue Mink 1969

This debut single by the veteran Brit sessioneers fronted by Madeline Bell had long since jumped the shark when Alan Partridge jumped around his Travelodge room singing it, stopping only to question whether “Chinky” was still an acceptable term. It’s dated, then, but winningly guileless, with – as the sight of a pub full of old socialists singing along to it on the jukebox will attest – a wonderfully uplifting chorus.

Cop Killer Body Count 1992

Ice T’s in-character reaction to the 1991 police beating of Rodney King begins with the stated desire to shoot every corrupt cop in the face. That’s one way to get your audience’s attention. The pummeling, consciously over-the-top piece of speed-metal that ensues was a significant piece of steam-letting on behalf of a community teetering on the brink; following the 1992 LA riots, Cop Killer was removed from the first Body Count album and remains devilishly hard to find.

And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda Eric Bogle 1971

There are a thousand anti-war songs, most angry, some sad, others defiant, but none with the novelistic scope and detail of this first-person tale of the battle of Gallipoli, written by a Scottish folk singer who emigrated to Australia while that country was fighting alongside the Americans in Vietnam. Told through the eyes of a rambler who answers his country’s call and returns minus his legs, it skews patriotic fraud like nothing else. Impossible to sit through its seven minutes with dry eyes.

Stop the Violence Boogie Down Productions 1988

Having lost his DJ partner Scott La Rock in a street shooting, Bronx rapper Lawrence Krishna Parker, aka

KRS-One, rejected his previous gangsta persona and reinvented himself as a self-styled teacher and voice of hip-hop’s conscience. His second album, By All Means Necessary, featured KRS posing as

Malcolm X on its sleeve, and this anthemic plea for social justice and a peaceful rap scene. Hip-hop listened intently to the digital reggae beats but ignored the message.

When the President Talks to God Bright Eyes 2005

Conor Oberst, aka Bright Eyes, campaigned for John Kerry on 2004’s Vote for Change tour, although his records made sure his political persuasions were never in doubt. This B-side, which he chose to play on

The Tonight Show with Jay Leno rather than promote an album, was as furious an attack on George Bush as any. Riffing on Dubya’s imagined relationship with God, Oberst lists (and it’s a long list) all the president’s failings with a brooding intensity and anger.

Small-town Boy Bronski Beat 1984

Written for a film sponsored by the Greater London Council called Framed Youth – Revenge of the

Teenage Perverts, Bronski Beat’s debut dealt with the story of a gay man’s attempts at escaping suburbia. Not the most obvious material for a Top 10 hit, then, and nor did Jimmy Somerville conform to everyone’s idea of a pop star. But his bravura vocal performance and the kind of synthpop backing that’s only now coming back into vogue helped propel it to No 3 in the UK charts. Those who preferred the 12” version found the telephone number of the London Gay Switchboard etched into its inner groove.

Between the Wars Billy Bragg 1985

During the miners’ strike, the Bard of Barking travelled to the coalfields, playing gigs to raise money for the miners and their families – and in the process, discovered a rich seam of traditional folk song. For this EP, the proceeds of which also went to the cause, he essayed versions of Which Side Are You On?, an American pro-trade union song from the 1930s, and Leon Rosselson’s The World Turned Upside

Down (itself an update of the 17th century Diggers’ Song). But the title track was his original, and just as powerful in its assertion of workers’ rights and dignity. Nor, of course, have lines like “I’ll give my consent to any government/ that does not deny a man a living wage” gone out of fashion.

Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud James Brown 1968

The first record credited to the Godfather of Soul as a solo artist captured the positive side of 60s black militancy with brilliant, funk-driven, call-and-response simplicity. But in his 1986 autobiography, Brown insisted that the song was “misunderstood” and that it “cost me a lot of my crossover audience”.

Perhaps it was the socialist implications of Brown’s rap about black self-sufficiency that disturbed Wasp

America, but the single still hit the US top 10.

Slavery Days Burning Spear 1975

Named for an African freedom fighter – Jomo Kenyatta – Burning Spear are roots reggae incarnate and

Slavery Days is less a pop song than a Rasta military chant. There’s neither bridge nor chorus, just lead singer Winston Rodney detailing the suffering of the slaves, the other members answering him with a question: “Do you remember the days of slavery?” The uplifting brass section is there as reminder that it’s not an invitation to self-pity, but a call to action.

Army Dreamers Kate Bush 1980

This demure chamber-folk waltz masks a deceptively sharp piece of political observation from Bush, ostensibly concerning British soldiers in Northern Ireland. Singing with a slight Irish lilt, she laments the boy who “should have been a father” but never even made it into his 20s. “It’s just so sad that there are kids who have no O-levels and nothing to do but become soldiers,” she said. “It’s not really what they want, that’s what frightens me.”

The Sun Is Burning Ian Campbell Folk Group 1964

The power of subtlety in protest music is brilliantly expressed by one of the earliest anti-nuclear songs, an unofficial anthem of the CND movement and Ban the Bomb marches. Originally sung with innocent clarity by his sister Lorna – and later covered by Simon and Garfunkel – Ian Campbell’s clever descriptiveness gradually subverts a scene of idyllic normality into a shocking climax as the sun falls to earth and “death comes in a blinding flash of hellish heat”.

Company Policy Martin Carthy 1988

Martin Carthy claims only ever to have written two songs, but he’d be hard pushed anyway to match this damning analysis of the cause and effects of the Falklands war. At the height of his powers both as an expressive singer and innovative acoustic guitarist, Carthy adapts the traditional song form to knit a particularly harrowing human tragedy into the context of a cold commercial enterprise and the gruesome triumphalism of the victory parades.

Rainin’ in Paradize Manu Chao 2007

Critics might scoff that Chao is little more than the patron saint of scruffy Eurorailers. But there’s little denying the strident urgency of this lead track from his most recent album, with its shrill guitars and provocative statements such as: “In Baghdad, it’s no democracy/ That’s just because… it’s a US country!”

Never mind that the chorus sounded as if it might have been esperanto: “Go masai, go masai, be mellow/ Go masai, go masai, be sharp.” Anyone?

Straight to Hell The Clash 1982

Joe Strummer’s most poignant and intellectually charged protest lyric is a mournful look at the displacement of immigrants and the personal effects of war. Over a percussive two-chord vamp, he connects the fates of unemployed British steelworkers, Puerto Rican immigrants and Amerasian war babies with haunting insight. MIA’s sample of the track for the superb Paper Planes signals a long overdue acknowledgement of the original’s power.

White Riot The Clash 1977

The Clash’s debut single immediately illustrated their ability to pen a rousing terrace-chant while simultaneously grappling with such thorny topics as class and race. Written following Joe Strummer’s involvement in the 1976 Notting Hill riots, it’s a simplistic yet committed call to arms for disaffected white youth, urging them to direct action in imitation of their black counterparts who, apparently,

“don’t mind throwing a brick”.

Running the World Jarvis Cocker 2006

In pop, the c-word is almost as loaded as the n-word. But surely no one could begrudge the ex-Pulp front man’s use of the taboo noun as he lays eloquently into the excesses of rampant capitalism and the selfperpetuating hegemony of bad men like no one else in British pop. He was right about Michael Jackson; he’s still right about class war in the era of crunched credit.

Alabama John Coltrane 1963

The murder of four girls in the Ku Klux Klan’s bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist church in

Birmingham, Alabama, on 15 September, 1963, proved a turning point in the civil rights movement in

America, and inspired Nina Simone’s Mississippi Goddam, Richard Farina’s Birmingham Sunday and this elegiac masterpiece. Coltrane apparently patterned his saxophone playing on Martin Luther King’s funeral speech, and Elvin Jones’ drumming rises to a crescendo that sounds like the surging tide of the struggle.

A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke 1964

Barrack Obama’s speechwriters knew where to go for inspiration on the night of his election success:

“It’s been a long time coming,” said the president, borrowing directly from this greatest of all civil rights anthems, before “but tonight, change has come to America.” Alas, Cooke died before he could witness the commercial success of this record, which was released as a single following his death in 1964.

Tramp the Dirt Down Elvis Costello 1989

Whether you feel it’s fair or not, when Margaret Thatcher finally dies, this bitter lament from Costello’s

Spike album will find itself on every ageing leftie’s stereo. The former Declan MacManus taps into both his Irish folk roots and early Dylan to ask whether the former Conservative prime minister can live with every “tiny detail” of her crimes against the working class, before stating that he’s only living to be able to dance on her grave. Possibly the most personally vituperative song ever recorded.

Brother Can You Spare a Dime? Bing Crosby 1932

Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney’s parable about the human indignity of hardship may have come out of the

American Depression of the 1930s, but it’s a telling soundtrack for any era of economic suffering. The gorgeous tune and the crooner’s effortless art enhance the bewilderment of someone grappling with shattered pride, but the song’s underlying bitterness is there in the opening line: “They used to tell me I was building a dream…”

Ohio Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young 1970

“Tin soldiers and Nixon coming/ We’re finally on our own/ This summer I hear the drumming/ Four dead in Ohio.” CSNY’s stomping slice of angry hippie rock was a rapid response to the Kent State shootings on

4 May 1970, when the Ohio National Guard shot four students taking part in a Vietnam war protest. Neil

Young saw a report in Life magazine, wrote the lyrics, recorded the song with the band and released it by June.

Thou Shalt Always Kill Dan Le Sac vs. Scroobius Pip 2007

A highly individual British rap, preaching the alternative gospel of Essex. Apart from attempting the impossible – i.e. make beards fashionable – Scroobius Pip’s engaging stream of consciousness takes colorful swipes at his pet hates, ranging from Coca-Cola and Nestlé to the NME and Hollyoaks. It carries as many contradictions as provocative truths, but Pip’s cultural sniping has persuasive wit. “Thou shalt not worship pop idols or follow lost prophets…” Indeed.

California Über Alles Dead Kennedys 1979

This jolting proto-hardcore debut rose out of DKs’ singer Jello Biafra’s fear of shonky new-age guruism spreading into politics, notably when California governor Jerry Brown stood for election on a platform of

Buddhist economics and exploring the universe. Biafra imagined a hippie-fascist future under his presidency worse than Orwell’s 1984, complete with organic poison gas chambers and “suede/denim secret police”. All lurching riffs and twitchy stops, it’s a rabid, paranoid punk classic.

16 Military Wives The Decemberists 2005

Colin Meloy and his gang of hardy Oregonians had spent their first two albums singing songs about rueful actors and Keith Waterhouse plays; but their breakout 2005 record, Picaresque, and this, its breakout hit, lifted them into a firmament of young American musicians sick of war and lies. The story of a feckless media and the men being sent to fight dumb wars is encapsulated in Meloy’s spruce denigration of facile 21st-century American culture.

Television: The Drug of the Nation The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy 1991

Gil Scott-Heron declared that the revolution would not be televised. This San Franciscan hip-hop crew set out to explain why. Ranting with an aged-wood authority reminiscent of Public Enemy’s Chuck D, front man Michael Franti charges the box with corroding freedom and popularizing ignorance, as keyboard player Rono Tse unleashes samples of adverts and warfare beneath. But Franti’s stern sloganeering is hitched to a loose-limbed, rolling rhythm, making it one of the catchiest lectures ever delivered.

Not Ready to Make Nice Dixie Chicks 2006

Now George Bush is widely considered the worst US president in history, it’s easy to forget that when

Dixie Chicks criticized the impending invasion of Iraq in 2003, he was an American hero. It provoked a vicious backlash, resulting in the de facto blacklisting of the band. This was their response. The music is standard mid-pace pop-country, but the lyrics crackle with anger. A genuinely moving song by three women brave enough to say what they thought when few others would.

Hurricane Bob Dylan 1975

Co-written with theatre director and Rolling Thunder Revue collaborator Jacques Levy, this hit single and track from the 1976 Desire album tells the tale of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a black boxer imprisoned for a triple murder that he and his supporters insisted he didn’t commit. Written in a richly cinematic style, the song highlighted a campaign that finally saw Carter released in 1988. Denzel Washington played

Carter in Norman Jewison’s 1999 film.

Maggie’s Farm Bob Dylan 1965

Cut in a single take, this reworking of the traditional Down On Penny’s Farm is seen by some as Dylan’s protest song against protest folk – and at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 it was his electric performance of it that seemingly so incensed Pete Seeger and co. But as ever with Dylan, it’s hard to pin down the meaning of each and every line; instead, what’s left – talking across the generations – is that snarling refusal to work for Maggie or for her brother, ma or pa.

Masters of War Bob Dylan 1963

According to Dylan this is a pacifistic song against war and not an anti-war song, though the distinction might be lost on many listeners. Taken from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, it is certainly the work of a young man, one who puts himself front and centre to denounce those that “build the death planes”. “I just want you to know/ I can see through your masks,” he whines, but in its arrogance the song carried a real power; one that was to find popular expression as the 60s wore on.

The Times They Are a-Changin’ Bob Dylan 1964

Although a little stiff and self-conscious, this remains, next to Blowin’ in the Wind, Dylan’s most significant anthem. Quickly adopted by the civil rights movement, it was taken as a comment on everything from the generation gap to the rise of the liberal left; today it simply stands as the ultimate articulation of the seismic cultural shifts of the early 60s. “I didn’t mean it as a statement,” Dylan later said. “It’s a feeling.”

When the Ship Comes In Bob Dylan 1964

A fine example of personal pique inspiring a song of universal relevance. Refused entry to a hotel – Joan

Baez eventually vouched for the scruffy, obscure folksinger – Dylan stomped upstairs to vent.

Channeling both Brecht and the Bible, he foresees the day when the “wise men” of the world will rise up to deliver a terrible judgment upon meddling, incompetent figures of authority: “And like Goliath, they’ll be conquered!” Truly rousing.

John Walker’s Blues Steve Earle 2002

One of the most significant political songs of recent times, and a notable attempt to dig into the mindset of John Walker Lindh, the alienated “American boy” who fought for the Taliban forces before his capture late in 2001. In doing so, Earle unearthed some uncomfortable home truths about US complicity in 9/11:

“I’m trying to make clear that wherever he got to, he didn’t arrive there in a vacuum,” he said.

Role Model Eminem 1999

Marshall Mathers’s greatest gift is his ability to couch morality tales in superficially offensive rhymes.

This Dr Dre co-production from debut album The Slim Shady LP hits the listener with a deluge of gross and puerile images. But the point is the ridiculous pressure on rappers to be “role models”, and our moral guardians’ insistence that our children will “tie a rope round my penis and jump from a tree” if a pop star tells them to. A satirical protest classic.

We Care a Lot Faith No More 1985

It’s hard to think of Faith No More without thinking of shock-tactician front man Mike Patton; but this defining FNM song was first recorded with early-years singer Chuck Mosely. Over an almost spookily sparse appropriation of 80s metal, bent out of usual shape so as to accommodate hints of hip-hop and weird electronics (before that was even remotely the done thing), Mosely mocks the fakery of

“compassionate” millionaire rock stars in the Live Aid era with acid aplomb.

Two Tribes Frankie Goes To Hollywood 1984

“When you hear the air-attack warning, you and your family must take cover…” Producer Trevor Horn reworked an insipid white funk version from a Peel session, and despite the vagaries of the lyrics, at the height of nuclear proliferation paranoia, this certainly sounded like a Very Important Thing. The sleeve depicted the US and USSR’s respective nuclear arsenals and it came with Annihilation, Carnage and

Surrender mixes, but it was the video that really rammed the point home: depicting Ronald Reagan and

Russian leader Chernenko knocking lumps out of each other, it’s still seldom seen on TV in full.

Respect Aretha Franklin 1967

When Otis Redding wrote it, he was asking for respect, and a little female succor. When Aretha Franklin sang it, she was demanding respect for an entire put-upon gender and, indirectly – thanks to the backdrop of the civil rights movement of the late 60s – an entire race. But there’s plenty of the naughty in the mix too, as Franklin’s sisters whoop it up on backing vocals and this polyvalent soul classic canters breathlessly to a close.

I Fought the Law Bobby Fuller Four 1965

First recorded by the Crickets and Sonny Curtis in 1959, and later covered by the Clash and many others

(including, disturbingly, Bryan Adams); but this was the definitive version. OK, the law always ends up winning and the song ostensibly mourns the girlfriend whom the jailed protagonist leaves behind; but with that line “I needed money, ’cause I had none”, with its foreboding pause, this is really a rebel’s charter.

Víctor Jara of Chile Dick Gaughan 1985

Anyone doubting the political power of song might ponder the brutal murder of the great Chilean activist Víctor Jara, whose music was considered sufficiently subversive to warrant his killing by General

Pinochet’s junta during the bloody, US-backed military coup of 1973. Adrian Mitchell’s moving poem – which recounts the story of Jara’s life and death – was set to music by Arlo Guthrie, but Dick Gaughan’s cold fury best captures its angry despair.

Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology) Marvin Gaye 1971

Eerily prescient. It’s a measure of the breadth of Gaye’s vision that he was able to turn his gaze away from the inner-city travails documented on the rest of What’s Going On and venture into eco-activism.

The languid melody and lush production sit at odds with the stark depiction of a world rapidly choking itself to death through overpopulation, pollution and general lack of environmental respect. You suspect that’s the whole point.

What’s Going On? Marvin Gaye 1971

Reluctantly released by Motown, who were dismayed by its downbeat social message, this remains a landmark in soul music’s politicization. Both a cry of confusion and a plea for tolerance, the song has personal resonance: the “brother, brother, brother” of the lyric is Gaye’s sibling Frankie, who served three years in Vietnam. Though the message is banal in places – “war is not the answer, only love can conquer hate” – its liquid groove and complex, layered harmonies remain eternally fresh.

The Message Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five 1982

Rap’s first great protest song almost didn’t happen. Neither turntable legend Flash nor most of the

Furious Five saw any future in rubbing the urban audience’s noses in the facts of ghetto life under

Reaganomics, and left the recording of this prowling funk nightmare to co-writers Duke Bootee and MC

Melle Mel. The Message went platinum in less than a month, and the group’s ensuing angry split mirrored the song’s pungent vision of a black America “close to the edge” of complete breakdown.

American Idiot Green Day 2004

More popular in the UK than the US, this lead single from the album of the same name was an open and uncomplicated assault on the policies of the Bush administration and the attitudes that sustained them.

“Well maybe I’m the faggot America,” sang Billie Joe Armstrong, “I’m not a part of a redneck agenda.”

Despite obvious pop overtones, this track, in its simplicity and ferocity, can lay legitimate claim to being punk music in the original sense.

This Land Is Your Land Woody Guthrie 1944

It’s not a little ironic that every American schoolchild learns this song, the communist sympathizer’s riposte to the unctuous God Bless America. Guthrie is on a magical realist hike across America’s promised land, endorsing a Native American belief that the land cannot be owned. A little-sung alternate verse makes explicit his disdain for private property; another verse sympathizes with the unemployed, making This Land… a secular hymn laced with political dynamite.

Okie from Muskogee <> 1969

Ostensibly deriding the back-sliding treachery of the counterculture – “We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street” – Haggard’s hippy-baiting redneck anthem is in fact an affectionate satire on the citizens of Middle America, for whom short hair, manly footwear, respecting authority and unquestioning patriotism stood as the nation’s guiding principles. The fact that the song sold millions at the height of the Vietnam war suggests that its subversive intent wasn’t always recognized.

On the Blanket Mick Hanly with Christy Moore 1980

Ireland’s powerful history of rebel songs gained some notable new additions during the hunger strikes of the 70s and 80s. None was more formidable than this outraged, deeply emotive protest about the treatment of the Maze prisoners demanding political status and refusing to wear prison uniforms. “If we stay silent we’re guilty, while these men lie naked and cold,” sang Moore and Hanly with quiet intensity

– at personal risk to themselves on the frontlines of Republican rallies and marches.

19 Paul Hardcastle 1985

Paul Hardcastle was a little-known English musician before he sampled dialogue from Vietnam Requiem, a documentary about the Vietnam war, over his stripped-back early-house backing track. The 19 in question was the alleged “average age of a combat soldier” in Vietnam. The song went to No 1 in the UK for five weeks. Hardcastle’s manager, Simon Fuller, renamed his company 19 Management and went on to manage the Spice Girls and David Beckham, and create Pop Idol. None of them received a hero’s welcome.

The Star-Spangled Banner Jimi Hendrix 1969

Less a protest song than rock’s greatest tone poem, recorded for posterity at the Woodstock festival in

1969. Hendrix uses his mastery of feedback, distortion and guitar effects to deconstruct the US national anthem, impersonating the sounds of human screams and “The rockets’ red glare/ Bombs bursting in air”, in protest at the Vietnam war. It remains a terrifying sonic experience and the precursor to some of rock’s most cynical tilts at American patriotism.

(We Don’t Need) This Fascist Groove Thang Heaven 17 1981

Early 80s irony in excelsis, as former Human League members Ian Craig Marsh and Martyn Ware and vocalist Glenn Gregory simultaneously protested against the rise of the right and poked fun at funk and their own electro-disco pretentions. The Sheffield trio’s debut single featured over-the-top slap bass, exhortations to “Hot yo’ ass!” and puns about Cruise missiles while being 100% sincere in its loathing of

Thatcher and Reagan. Radio 1’s Mike Read didn’t get the joke and banned it.

Strange Fruit Billie Holliday 1939

The central metaphor of black lynch-mob victims hanging like fruit from blood-stained trees, with their “bulging eyes and twisted mouth” remains unforgettable and genuinely haunting. Adapted to music by Jewish academic Abel Meeropol from his own poem, Billie Holiday’s spellbinding original is run a close second by Nina Simone, whose 1965 version from her Pastel Blues album, recorded at the height of the civil rights struggle, displays a near-perfect mix of sorrow and anger.

Check Out Your Mind The Impressions 1970

Curtis Mayfield was always the most sophisticated advocate of black power among his peers; this cut – from the album of the same title, his last album with the Impressions – saw him eschew rabble-rousing

(and perhaps it was a spurning of the new psychedelia, too) in favor of a tougher message – namely, remember you can always think for yourself.

People Get Ready The Impressions 1965

Released almost two years after the historic March on Washington, Curtis Mayfield’s vision of faith in a train to freedom was the musical version of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech. A gentle tapestry of sweet soul harmonies, elegant orchestration and gospel imagery, People Get Ready is a song of reconciliation that rejects racial barriers and develops the great American tradition of symbolic train songs. Only “the hopeless sinner whom would hurt all mankind” is denied passage to this promised land.

The Eton Rifles The Jam 1979

On which Paul Weller told the story of a group of unemployed socialists being heckled on a march by a cadet corps from Eton college. Conservative leader David Cameron is reported to have said: “I was one, in the corps. It meant a lot, some of those early Jam albums we used to listen to. I don’t see why the left should be the only ones to listen to protest songs.” Prompting Weller thus: “Which part of it didn’t he get?”

Going Underground The Jam 1980

“You’ll see kidney machines replaced by rockets and guns.” With that line Paul Weller crystallized the feelings of many as Margaret Thatcher’s government plunged the nation deep into recession and the

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan placed the cold war in the microwave for a quick reheat. It was angry, but no rant, and the music (especially Bruce Foxton’s glowering bass) packs a punch that transcends the times. The first single to go straight to No 1 since Slade’s Merry Xmas Everybody, but a very different beast.

The Village Green Preservation Society The Kinks 1968

“God save strawberry jam and all the different varieties,” they sang, adding to that list little shops, china cups and virginity, Tudor houses, antique tables and more. No, it wasn’t John Major in old-maids-cyclingto-work mode, but Muswell Hill’s finest. Deftly, Ray Davies made you pine for the old ways now being abused – while also creating the impression that he might never sign up to this vision of Middle England.

Zombie Fela Kuti 1977

Taken from the album of the same name, Zombie is a 12-minute assault on the Nigerian government and it soldiers that brought about violent reprisals by state forces and led to the death of Kuti’s mother.

The lyrics – “Fall in, fall out, fall down, get ready” – were sung in English in order to reach a broader audience but are backed by the fabulously rich mix of Afro beat at its most heady. Horns, guitars and vocals weave in and out, but the rhythm section remains constantly frenetic throughout.

The Proud Talib Kweli 2002

Not since Public Enemy were at their peak has a rapper packed his rhymes with such political force, even if The Proud’s musical tone is markedly more mellow than anything the Bomb Squad cooked up. “The president is Bush, the vice-president’s a Dick/ So a whole lot of fuckin’ is what we gon’ get,” was the lightest moment on a song that raged against black poverty, post-9/11 patriotism, media manipulation and police racism.

The Bourgeois Blues Leadbelly 1938

Invited to Washington at the behest of Alan Lomax in order to contribute to Lomax’s project at the

Library of Congress, Leadbelly and his wife were greeted with both condescension and racial discrimination by the city’s residents. This much-covered song, not least by Leadbelly himself, tells of that event with special emphasis placed on the class of those he met, the word “bourgeois” being

repeated 15 times in five verses. While eight other Leadbelly recordings now reside in Congress, this one does not.

Give Peace a Chance John Lennon 1969

Although nobody was talking about Bagism, apart from John and Yoko, Give Peace a Chance became as recognizable a call to disarm as Guernica or the CND sign. Lennon had used the phrase as an answer to a reporter during the Montreal bed-in. He liked it so much that he set it to music on a cheap four-track with the help of Allen Ginsberg and others. Even Lennon admitted the song wasn’t his finest, but as a peace chant, it’s untouchable.

The Ballad of Sharpeville Ewan MacColl 1960

On 21 March 1960 a peaceful black demonstration against apartheid in the Transvaal township of

Sharpeville ended in massacre when the police turned their guns on the unarmed demonstrators, killing

69 and wounding hundreds of others. MacColl’s response was immediate: he sat down and wrote one of his most epic songs, coldly recounting the distressing details of the tragedy in the manner of the old broadside ballads.

Eve of Destruction Barry McGuire 1965

Presented to the Byrds as the sort of Dylanesque tune they might like, the Los Angeles band turned down PF Sloan’s song, leaving a fledgling rock singer from Oklahoma with one of the defining hits of the

60s. War in the Middle East, nuclear proliferation, the civil rights struggle (“Think of all the hate there is in Red China/ Then take a look around to Selma, Alabama”): it all added up, although McGuire later argued this wasn’t a protest song per se, telling one interviewer: “If you go to a doctor and he tells you that you have a melanoma that needs to be removed, do you call him a protest doctor? I don’t think so.”

Material Girl Madonna 1985

If Gordon Gekko’s assertion that “greed is good” in the film Wall Street seemed to sum up the worst aspects of 80s yuppiedom – well, what about Madonna here? It wasn’t simply the vulgarity of the lyrics, it was the smug way in which she sang them, sneering at her fictive suitors and by extension anyone who wasn’t “the boy with the cold-hard cash who’s always Mr. Right”. Problem was, this prime slice of pop was so damned catchy.

Suicide Is Painless (Theme from M*A*S*H) Johnny Mandel 1970

With lyrics written by Robert Altman’s then 14-year-old son Mike (who reportedly made more than his dad did from directing the film M*A*S*H), this melancholic theme tune is one of those odd songs that’s more familiar as an instrumental. Would people be quite so fond of it if they were singing along to lines such as: “The sword of time will pierce our skins/ It doesn’t hurt when it begins/ But as it works its way on in/ The pain grows stronger, watch it grin”?

Redemption Song Bob Marley 1980

”Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery,” Marley sang, borrowing from a Marcus Garvey speech.

“None but ourselves can free our minds”. Given a sparse acoustic treatment, this was the last track on his last studio album, Uprising, and as such his perfect testament. It addressed his Rasta beliefs, but the message that’s echoed down is universal.

Zimbabwe Bob Marley and the Wailers 1979

Written by Marley during his pilgrimage to Ethiopia in 1978 and recorded for his album Survival – the cover of which depicted the flags of Africa’s independent nations – this stirring song in support of the freedom movement in Rhodesia became its own self-fulfilling prophesy. The opening verse declared

“Every man gotta right to decide his own destiny”, and on 17 April 1980 Marley found himself singing it on the Zimbabwe’s independence day in front of an audience that included Robert Mugabe, Indira

Gandhi and Prince Charles.

Kick Out the Jams MC5 1968

Despite being the keynote song of the most militant proto-punk band of the 60s, Kick Out the Jams doesn’t have a protest lyric. The rebellion comes from the explosive intensity of Wayne Kramer’s guitar, and singer Rob Tyner’s opening holler: “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!” The Detroit combo’s debut album was recorded live in their hometown, and the title was a band in-joke about the “jamming” of rival bands. The controversy caused by Tyner’s swearing got them kicked off the Elektra label.

Big Yellow Taxi Joni Mitchell 1970

The Canadian icon’s only hit single is one of the most playful of all protest songs. Inspired by a trip to a hotel in Hawaii where they’d “paved paradise and put up a parking lot”, Mitchell brings the political to the personal by veering from ecology to a taxi taking away her “old man”, because, whichever way, “you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til its gone”. The delighted giggle at the song’s end is the icing on the cake.

Trouble Every Day The Mothers of Invention 1966

“Well I’m about to get upset from watching my TV/ Been checking out the news until my eyeballs fail to see…” Tucked alongside the hippie parodies, sonic experiments and songs such as Help, I’m a Rock on the Mothers’ debut Freak Out! came Frank Zappa’s bluesy analysis of watching the Watts riots in Los

Angeles on “that rotten box”. It still sounds like one of rock’s most articulate – and prescient – takes on the issue of media manipulation. What would he have made of Sky News?

Police and Thieves Junior Murvin 1976

In 1976, Junior Murvin pitched up at Lee Perry’s legendary Black Ark studio to audition for the maverick producer. The song he brought with him became the rude boy anthem of the year in Jamaica and a huge sound system hit in Britain. On Police and Thieves, Murvin’s extraordinary falsetto, modeled on Curtis

Mayfield, floats on a shimmering, otherworldly Perry production that remains one of the high water marks of reggae music. Reworked by the Clash on their debut album, and its rhythm used for countless

Jamaican DJ outings, the original remains untouchable.

Short People Randy Newman 1977

So what’s the problem with short people? Well, “they got little hands, and little eyes; and they walk around, tellin’ great big lies,” and that’s just for starters. Newman remains one of our finest satirists, and one of his greatest gifts is economy: there’s no need to labor the point here, and he doesn’t. But he does make the point that these perfidious short people “wear platform shoes on their nasty little feet”.

I Ain’t Marching Anymore Phil Ochs 1965

Written as the Vietnam war was starting to escalate, Ochs’s defiant soldier-song ties together centuries of bloody US military history to powerful effect, told over a simple folk strum. The lyric prises the generation gap wide open – “It’s always the old who lead us to war/ Always the young who fall” – while

Ochs provocatively described his signature tune as bordering “between pacifism and treason, combining the best qualities of both.”

Monkey Gone to Heaven Pixies 1989

Best described by Rolling Stone’s David Fricke as “a corrosive, compelling meditation on God and garbage”, this lead single from the Boston indiemeisters’ biggest album, Doolittle, made the hitherto unexplored connection between Hebrew numerology and eco-awareness. Over a mournful ballad-rock

adorned by a string quartet, composer Black Francis ponders oceans full of New Jersey sludge and dead animals, offering a howled warning that “If man is five… then the Devil is six… and God is seven!”

Streets of Sorrow/Birmingham Six The Pogues 1988

Released while the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four were still in jail, this was to the Troubles as

Free Nelson Mandela was to South Africa. But where the Special AKA were persuasive, the Pogues were simply furious. Segueing from the folksy Streets of Sorrow, bemoaning Northern Ireland’s tragedy, it slams into McGowan’s punk-driven denunciation of British justice. Fearful of Thatcher’s “oxygen of publicity” laws, gutless broadcasters banned it and a live performance on Friday Night Live was abruptly interrupted by adverts.

In the Ghetto Elvis Presley 1969

It took a protest song to revive the recording career of one of pop’s most apolitical artists. Written by country composer Mac Davis, this elegant gospel ballad saw the King tell a poignant tale of the cycle of

American poverty and crime, as its poor, young male protagonist lives a short and brutal life that begins and ends with his mother’s tears, and is then immediately repeated by another family in the slums of

Chicago. Original title? The Vicious Circle.

Come Together Primal Scream 1990

Classic soul and the American civil rights movement meant as much to Bobby Gillespie as the acid house scene, so it made sense to let producer Andy Weatherall preface this alternative rave anthem with a sample of Jesse Jackson declaiming: “This is a beautiful day, it is a new day, we are together.” Church organ and police sirens helped build something rapturous over the 10 minutes that followed. Never mind that Gillespie later blotted his copybook, writing Star, by talking about Rosa Parks as if she, like

Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, had already gone to visit that great gathering in the sky.

Sign o’ the Times Prince 1987

This dark, electro funk classic is Prince’s peak; a political statement from a star so admired that it seemed like the world stopped to listen. What they heard was a bravura update of Riot-era Sly Stone and an apocalyptic lyric taking in Aids, gangs, hurricanes, child poverty, drugs and the Star Wars nuclear programme, but largely inspired by the Challenger shuttle disaster. “And everybody still wants to fly,”

Prince sighed, baffled by Reagan-era values.

Sam Stone John Prine 1971

Rather than protest the war in Vietnam directly, singer-songwriter Prine addressed its aftermath at the human level. The song’s protagonist returns home to his wife and family with a shrapnel wound that leaves him needing morphine and soon enough – as the chorus repeats to us – “there’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes”. It might have been the soundtrack to The Deer Hunter.

Bring the Noise Public Enemy 1987

Blessed with a rapid-fire Chuck D lyric so stunning that half the lines became hip-hop slogans, Bring the

Noise is as bewildering as it is exhilarating. Taking the re-emergence of black militancy as its launch pad, the song sees production team the Bomb Squad reach their peak of organized noise; a wall of sampled beats, horns, guitars, voices, sirens and subsonic bass taken at punk-rock tempo. Its shout-out for Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan is still contentious.

Fight the Power Public Enemy 1989

Elvis was a hero to most, even to Chuck D, Public Enemy’s ringleader once confessed, but he took

Presley’s name in vain and called him a racist to make the point that “most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps”. For a generation, the song is fixed in the imagination as the soundtrack to Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing, but the Bomb Squad’s blistering production will always serve as a call to arms.

How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? Blind Alfred Reed 1929

Looking for a soundtrack to economic woes? Reed was a contemporary of Jimmie Rodgers and the

Carter Family and penned this standard, which was later covered by Ry Cooder and Bruce Springsteen.

“There was once a time when everything was cheap, but now prices nearly put a man to sleep,” he sang, adding with mordant humor: “When we pay our grocery bill, we just feel like making our will.”

Fall On Me REM 1986

A song from Life’s Rich Pageant, the album on which Michael Stipe dumped his penchant for obscure lyricism to facilitate a developing sociopolitical agenda. Their first anthem, Fall On Me is about the effects of acid rain – “Buy the sky and sell the sky” – although Stipe has claimed that it is about

“oppression” in general. Pitched somewhere between folk and rock, the lovely counter-melody spills into a gorgeous, over-lapping three-part harmony on the chorus.

Glad to Be Gay Tom Robinson 1978

Peter Tatchell once called this “the musical equivalent of the Gay Liberation Front Manifesto”, and there was certainly no denying the caustic sarcasm of lines such as: “Read how disgusting we are in the press/

The News of the World and the Sunday Express/ Molesters of children, corruptors of youth/ It’s there in the paper, it must be the truth.” The trick was that Robinson came up with a chorus so catchy that even the readers of said newspapers would likely be tempted to join in for a sing-along.

Street Fighting Man The Rolling Stones 1968

No song captured both the exhilaration and the ultimate failure of the rebellions of 1968 like this ambiguous anthem. While the ringing acoustic guitar and monstrous beat punch home the adrenalin thrill of “marching, charging feet”, Mick Jagger, inspired by the London anti-Vietnam war demonstration of March ’68, sees the agitations in “sleepy London town” as little more than violent fun for po’ boys who’d rather be singing in rock’n’roll bands. A masterpiece of prophetic cynicism.

I’m Coming Out Diana Ross 1980

It was fitting that such a perfect example of the subversive qualities of manufactured pop happened on

Motown. Ross’s biggest album, Diana, was her last for Berry Gordy’s legendary label and was famously written and produced by Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of disco kings Chic. Knowing that the former

Supreme had a large and loyal gay following, they gave her a thinly disguised gay liberation anthem and looked on proudly as it hit the US Top 5.

Now That The Buffalo's Gone Buffy Sainte-Marie 1964

Herself a Cree, Buffy Sainte-Marie has written a whole raft of superb songs about the plight of the First

Nation and Native American peoples – but this painful yet poetic account of a history of broken treaties and promises ranks as the best. Sainte-Marie’s naturally tremulous voice and the simplicity of the melody add further poignancy to the shame loaded into the song and the plea for help and understanding she demands to right the wrongs.

Days of Fire Nitin Sawhney 2008

How to respond to the events of 7/7 and the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in London? Rather than serve up a slice of polemic, Sawhney set a simple acoustic melody against the narrative of a young

MC called Natty, who’d followed de Menezes on the next train into Stockwell station. The refrain “it all went slow motion... now we’re all in slow motion” freezes the action but also captures the confusion that followed “the days of fire”.

Whitey On the Moon Gil Scott-Heron 1970

One of Scott-Heron’s most memorable rhymes, and one that surely touched many white liberal nerves.

How dare the US federal government, Gil wondered over little else but a drum beat, spend incomputable amounts of money sending people into space when so many African-Americans can’t afford healthcare? Shockingly, with the monetary disparity between black and white in America still vastly disproportionate, the song still resonates. Except this time, Whitey’s being bailed out by the Fed.

We Shall Overcome Pete Seeger 1963

Pioneering folkie Pete Seeger helped popularize We Shall Overcome – which had already evolved from an old slave chant into a Methodist hymn – as a civil rights anthem, belting it out in 1963 to a crowd of

300,000 during Martin Luther King’s March on Washington. The simple message of hope and endurance retains its power. When Bruce Springsteen recorded his 2006 album of protest songs made famous by

Seeger, this was a shoe-in as the title track.

I’m Gonna Be an Engineer Peggy Seeger 1973

Avoiding the aggressive dogma and ranting sound bites that dulled political doctrines in later eras, Peggy

Seeger constructed a folkie story song of such cogent morals and lyrical wit it proved the perfect soundtrack for the march of feminism and a telling anthem for the international women’s movement.

Beneath the jauntily engaging narrative about one woman’s quest to break into a man’s professional world, she takes a scathing scalpel to society’s sexist indoctrinations.

Anarchy in the UK Sex Pistols 1976

The secret of the Sex Pistols’ impact doesn’t lie in their debut single’s powerhouse guitars, or sing-along melody, or even the devilish glee of the words. It lies in the friendliness of Johnny Rotten’s voice, which, even when he cackles maniacally or howls with sore-throat rawness, still manages to make this seminal vision of a country where passers-by are routinely destroyed feel as much like a comical invitation as an apocalyptic threat. It still sounds revolutionary and revelatory.

God Save the Queen Sex Pistols 1977

Starring Johnny Rotten as the little boy from “The Emperor’s New Clothes” with Queen and Country in the all-together while Britain tried to celebrate the Silver Jubilee, the target of God Save the Queen’s ire wasn’t Her Majesty, but “England’s dreaming” of ancient empires and class deference while the truth was that there was “no future” for most of its subjects. Did it change anything? Well… does anyone remember the Golden Jubilee?

If the Kids Are United Sham 69 1977

It’s easy to forget just how violent late 70s youth cults were. Sham 69’s plea for unity can seem a tad laughable but they effectively had their career stymied by an over-lairy audience. Over a riff recycled from the Stooges’ No Fun, Jimmy Pursey seizes his chance to wax idealistic – “Take a look around you/

What do you see/ Kids with feelings like you and me” – but it’s that terrace bruiser of a chorus that gives

Kids its dumb genius. The video has Pursey hugging a black youth (“All right, mate?”); the NF skinheads whose stage invasions prematurely halted Sham’s live career weren’t quite so chipper.

The Internationale Sheffield Socialist Choir 1992

Originally written as a defiant rallying call in 1871 by Eugène Pottier in response to the crushing of the

Paris Commune, its rousing tune was added 17 years later by Pierre de Geyter and it was set to become the international socialist anthem. Translated into hundreds of languages, notable versions include those by Ani DiFranco and Utah Phillips, Carla Bley, Robert Wyatt, Billy Bragg and the suitably stirring

Sheffield Socialist Choir. Come the revolution, they won’t be singing “Here we go, here we go, here we go…”

To Be Young, Gifted and Black Nina Simone 1970

Composed by Simone - with lyricist Weldon Irvine - as a posthumous tribute to her friend, the black playwright Lorraine Hansberry, this is a heady hymn of affirmation, urging the world’s black youth population to view their ethnic heritage as a blessing rather than a curse: “There are a billion boys and girls/ Who are young, gifted and black/ And that’s a fact!” Later covered, somewhat bizarrely, by Elton

John.

Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey Sly and the Family Stone 1969

This dark, hard psychedelic soul track from the Stand! album prefaced Act Two of Sly Stone’s profound impact on soul and rock music. The song is not a shaken fist at white racists, but sees Sly’s sister Rose singing a one-verse observation of a fight where she “heard two voices ring/ They were talkin’ angry to each other… And neither one could change a thing”. An enlightened pessimism that fuelled Sly’s seminal

1971 album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On.

Swimsuit Issue Sonic Youth 1992

New York’s art-punk doyens bit the hand that fed them on this incendiary track from their second major-label album, Dirty. As the scuzzy white noise of Swimsuit Issue creates a psych-rock wall-of sound, composer and bassist Kim Gordon sings from the perspective of a secretary at Sonic Youth’s label who has been harassed by a male executive. But she isn’t a victim for long. “You really like to schmooze,”

Gordon sneers. “Now you’re on the news.”

Revolution Spacemen 3 1989

While their British indie peers were largely content to peruse their shoes, Rugby’s finest drone-rock avatars spent the late 80s perfecting the connections between lysergic introspection and rock’n’roll radicalism. Peter “Sonic Boom” Kember and future Spiritualized main man Jason Pierce reached their hypnotic peak on this stunning, space-age-Stooges single, with Kember reasoning, convincingly, that it takes “just five seconds” for the enthralled listener to commit to overthrowing the status quo. A record to burn stuff to.

Ghost Town The Specials 1981

The 2-Tone stars’ peak moment famously hit No 1 in the UK charts in the very week that riots tore through the poorest boroughs of Britain’s inner cities. Inspired by the 20% unemployment rate reached in 1981 in their hometown of Coventry, Jerry Dammers’s haunting reggae anthem described the ensuing social chaos with devastating accuracy, warning that “the people getting angry”, but also despairing that the violent anger that should have been aimed at Thatcherism was turning the young working class against one another.

Free Nelson Mandela The Special AKA 1984

Few protest songs achieve their stated aim, but this ebullient Afro pop anthem definitely played its part.

Beloved of left-wing discos and adopted by South African Mandela supporters, this big-band plea for the release of Robben Island’s most famous prisoner also persuaded its composer Jerry Dammers to quit music for full-time anti-apartheid activism.

American Skin (41 Shots) Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band 2000

Springsteen’s lament for Guinean immigrant Amadou Diallo – shot 41 times by New York City police officers for reaching for his wallet in 1999 – led to the unthinkable: Bruce being booed at Madison

Square Garden. The track, recorded for a live E Street reunion record, also marked the moment in which

Springsteen was brought back from the critical and commercial wilds to become the documenting voice of modern America, something he confirmed with 2002’s majestic The Rising album.

Born in the USA Bruce Springsteen 1984

The title track of the Boss’s biggest album is a cautionary lesson for the composers of ironic protest songs. The US right heard the clarion call of the chorus and persuaded Ronald Reagan to use an implied

Springsteen endorsement in a September 1984 campaign speech. Fans heard the furious denunciation of America’s use of working-class men as Vietnam cannon fodder in the verses and knew that the song was a critique of the exploitation of patriotism.

War Edwin Starr 1970

Producer Norman Whitfield gave the song to the Temptations, but their original lacked a certain intensity, and even so they were worried about potential controversy. Enter one of Motown’s secondstring acts, who re-recorded the tune, aided by the Undisputed Truth on backing vocals and a storming horn section. No one could pretend that the lyrics were up to much: “War can’t take life, it can only take it away,” Starr ended up observing; but his extraordinary vocal take twinned his place in history with the song.

Monster Steppenwolf 1969

This three-piece suite charting the history of America from the founding fathers’ dream, via genocide against the Native Americans and slavery, to a nightmarish landscape of “cities turned into jungles” appealed to a curiously patriotic sense of liberty. The splenetic scowl in John Kay’s voice and the galeforce fury of Larry Byrom’s guitar playing added up to something suitably apocalyptic.

Suspect Device Stiff Little Fingers 1978

John Peel heavily supported this Belfast punk band’s vicious debut single, featuring a lyric (co-written by music journalist and SLF manager Gordon Ogilvie) that compared angry Belfast youth with the bombs that ripped Northern Ireland apart at the height of the Troubles. The other star was the sandpaperthroated howl of front man Jake Burns, who reached a state of near-apoplexy as he imagined himself

“the suspect device the army can’t defuse”, set to “blow up in their face!”

The Man Don’t Give a Fuck Super Furry Animals 1996

Like many songs with a rude word in the chorus, Super Furry Animals’ unofficial anthem is an outburst poised between anger and joy. Sampling Steely Dan’s Show Biz Kids to mantric effect, The Man… was dedicated to impolite Cardiff City footballer Robin Friday. But like James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, singer Gruff Rhys takes unfocused aim at pretty much everything (TV, the downtrodden masses), making

SFA’s prize pogo moment a one-size-fits-all rebel song.

Long Walk to DC The Staple Singers 1968

Starting in gospel, culminating in soul via folk and protest songs, the Staple Singers were the civil rights movement made music. Long Walk to DC was a celebration of Martin Luther King’s 1963 March on

Washington (five years after the event, but never mind) and their first record for Stax. Although the singing family hailed from Chicago, the guitar intro was pure Delta blues and the chugging rhythm exhibited the resolution and optimism that the group embodied so perfectly.

Peace Train Cat Stevens 1971

Forget the banal lyrics (“Why must we go on hating, why can’t we live in bliss?” are questions that remain unanswered) and cast aside cynicism (Cat Stevens himself would introduce this song from the stage by saying “It’s made me a lot of money”); banish, too, thoughts of Salman Rushdie and Yusuf

Islam’s unfortunate remarks pertaining to him. The melody and a performance of wide-eyed innocence combine to make believers of anyone.

The Killing of Georgie (Part I and II) Rod Stewart 1976

In these days of changing ways, so-called liberated days, a story comes to mind of a friend of mine,” sang Mr. Da Ya Think I’m Sexy, before embarking on this tale of the murder of a pal whose only crime was his sexuality. The melody leans first on Bob Dylan’s A Simple Twist of Fate, and then on the Beatles’

Don’t Let Me Down – but the tenderness that Rod brings to bear makes it its own affecting statement.

BYOB System Of A Down 2005

The most committed agitprop band ever signed to a corporate label, these Armenian-Californian metal heads hit satirical pay dirt with this protest single against the Iraq war. The dark comedy comes from the boy-band pop chorus and its invitation to a desert party where, as the title implies, American soldiers bring their own bomb. But the point is the song’s rabid positing of the age-old question: “Why don’t presidents fight the war? Why do they always send the poor?”

Dad’s Gonna Kill Me Richard Thompson 2007

In his long and illustrious career, Thompson has seldom written anything that could be construed as a protest song before this searing indictment of the Iraq war. The “Dad” in the title is Baghdad and, over searing guitar, Thompson’s novel ploy is to use the actual language of serving soldiers to paint a gory picture of their misery, fear and bewilderment. Its raw power has earned equal measures of hatred and gratitude from the families of those he’s singing about.

Legalize It Peter Tosh 1976

Former Wailer and occasional Rolling Stones collaborator Winston Mcintosh was always the most militant of the Jamaican rasta singers. This title track from his debut solo album became a global anthem for dope smokers, with its strident roots sound and stoned demands to legalize marijuana. Tosh liked to make up words; hence his claim that dope cured flu, asthma, tuberculosis “and even umara composis”.

He was murdered by gunmen in his Jamaican home in 1987.

Keep Ya Head Up Tupac 1993

Hip-hop has a long and shameful record of misogyny, so it’s heartening that one of its biggest stars attempted to redress the balance. Keep Ya Head Up apologizes for the casual insults directed at women and the denigration of welfare mothers and takes an impeccably liberal pro-choice stance, all without ever sounding mawkish or insincere. It’s one of hip-hop’s most profoundly soulful moments - pity he later blew it by being convicted of sexual assault.

Sunday Bloody Sunday U2 1983

Definitely U2’s finest protest song, if not their finest of all, Sunday Bloody Sunday’s tirade against the abhorrent dumbness of sectarian violence is one that can be translated from the streets of Derry to

Gaza, Iraq and Helmand today, Bono’s despairing “How long must we sing this song?” encapsulating a generation’s frustration with the Troubles and war in general. Or, as Alan Partridge put it: “What a great song. It really encapsulates the frustration of a Sunday, doesn’t it?”

We Are the World USA for Africa 1985

The year after Bob Geldof’s Band Aid asked the western world “Do they know it’s Christmas?” the assorted grandees of American popular music issued their, far superior, response. Incorporating solos by everyone from Michael Jackson to Bob Dylan via Huey Lewis, it was a starrier effort, but also took the sensible option of not talking about victims of the Ethiopian famine as if they lived on another planet. As

Diana Ross sang, if a little cryptically: “There’s a choice we’re making/ We’re saving our own lives.”

Get Up, Stand Up The Wailers 1973

One of the last songs recorded by the original Wailers trio, Get Up, Stand Up is a signature tune of both

Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, who shared lead vocals. Though notionally a rejection of Christianity and assertion of their own Rasta faith, it works instead as a rallying cry for the oppressed. After their first

Island Records album pandered to rock audiences, this showed the Jamaican icons restaking their own ground, defiant and inspirational.

The Day After Tomorrow Tom Waits 2004

A gently swaying ballad telling the tale of a 21-year-old Illinois soldier posted in Iraq, yearning for the comforting banalities of life back home: sweeping snow, raking leaves, the simple life. Released on

Waits’s Real Gone album, the song refuses to take sides or hector, instead deriving its considerable emotional power through poignant understatement. “Tell me, how does God choose?” asks the bewildered soldier. “Whose prayers does he refuse?”

The Old Man’s Back Again (Dedicated to the Neo-Stalinist Regime) Scott Walker 1969

Probably the closest Noel Scott Engel ever got to being funky, this highlight from the acclaimed Scott 4 album takes protest against the oppression of the Soviet regime on an unlikely trip into cool and mellow lounge crooner territory. Walker’s rich baritone carries a poetic lyric about the USSR returning to the excesses of Stalinism, where a woman watches her lover taken away, while “Teardrops burned her cheeks/ For she thought she’d heard/ The shadow had left this land”.

Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do) Wham! 1982

By the time of Club Tropicana, Wham! looked to have bought into the Thatcherite dream, but George

Michael’s heart (as he proved later with solo hits such as Shoot the Dog) was always in the right place.

This slice of white-boy funk, with its very 80s rap celebrating dole culture, proved utterly infectious: “Say

DHSS, now the rhythm that I’m given is the very best!” indeed.

My Generation The Who 1965

The invention of punk rock 10 years before the fact. The Who’s most totemic song was allegedly inspired by Pete Townshend’s anger that his 1930s hearse had been towed from a street in Belgravia at the behest of the Queen Mother. But its status as rock’s most influential youth rebel song lies with the

Neanderthal two-chord thrash, the censorship-baiting “F-F-F… fade away!” stutter, and the arrogance with which Roger Daltrey insists: “Hope I die before I get old.”

You Haven’t Done Nothin’ Stevie Wonder 1974

No artist has ever made agitprop sound as celebratory as the former Stevland Judkins Morris. And this furious deep-funk sneer at the presidency of Richard Nixon, featuring the Jackson 5 on backing vocals, saw Wonder at his most relevant. Released as a single and on the album Fulfillingness’ First Finale, it demanded: “We want the truth and nothing else.” Both hit the US No 1 spot just as the Watergate scandal finally forced Nixon’s resignation.

The Cottager’s Reply Chris Wood 2008

Nominated for Best Original Song at this year’s BBC Folk awards, Wood’s viciously wry morality tale wraps a multitude of sharp edges into one conversation between the owner of a cottage in the

Cotswolds and a bloke in a 4x4 trying to buy it off him. Adapted from a Frank Mansell poem, it has plenty to say about English heritage and modern mores, and is made all the more delicious by Wood’s teasing delivery.

Asbestos Lead Asbestos World Domination Enterprises 1985

Emerging from the same squatter culture as art collective the Mutoid Waste Company, Keith Dobson and co took a blowtorch to 80s yuppiedom. Snarled phrases – “Equal opportunity! Except if our pedigree dogs don’t like the smell of your children…” – emerged from squalls of guitar, bolted to a rhythm section that would bring Sly and Robbie to mind if the Jamaican double act were the types to walk their dogs on strings.

Shipbuilding Robert Wyatt 1982

Written by Elvis Costello in response to the Falklands war, Shipbuilding is that rare thing: a protest song full of nuance and subtlety. The slice-of-life lyric acknowledges the terrible paradox of the conflict providing jobs for those at home and body bags for those off to fight, but there’s little in the way of hysteria or dogma, just a general sadness reflected in the careworn vocals of 70s avant-garde veteran and committed Marxist Robert Wyatt.

Harrowdown Hill Thom Yorke 2006

By his own admission, the Radiohead front man’s first solo single is “the most angry song I’ve ever written in my life”. It concerns weapons expert Dr David Kelly, who committed suicide in 2003 on

Harrowdown Hill near his home in Oxfordshire. Or did he, queries Yorke on this digital funk jewel whose tasteful beginning cloaks a burgeoning sense of dread. “Did I fall or was I pushed?” he wails, his tone betraying his disbelief of the official line.

Rockin’ in the Free World Neil Young 1989

Inspired by a chance remark from Crazy Horse member Frank “Poncho” Sampredo, this stunning powerhouse protest anthem from the Freedom album signaled Young’s return to form after his 80s decline. Based on the same withering, faux-patriotic sarcasm as Springsteen’s Born in the USA, Young uses a surging Crazy Horse riff to launch into the domestic and foreign policies of the first president

Bush. The song became an anthem for the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Southern Man Neil Young 1970

Not many songs can be credited with starting a feud, but Young’s depiction of the American south as a place of “screaming and bullwhips cracking” made Alabama boogie men Lynyrd Skynyrd spit their grits into their gravy. The lyric is matched by some equally splenetic guitar outbursts and, though Skynyrd’s

Sweet Home Alabama, with its “I hope Neil Young will remember/ A southern man don’t need him around” taunt, sounds great at weddings, this is still a technical knockout for the grumpy Canuck.