Coming to Terms with the New Age 1820s to

advertisement

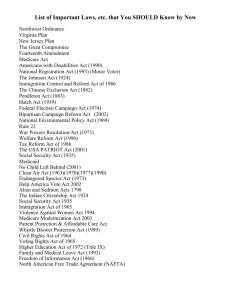

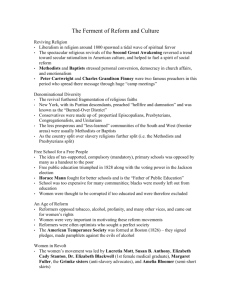

Chapter 13 Coming to Terms With the New Age, 1820s—1850s “Americans love their country not as it is but as it will be.” Foreigner Francis Grund “Why Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous.” Lucretia Mott, 1848 Introduction Lewis Tappin, Roger Baldwin Angelina and Sarah Grimke, Dwight Weld John Humphrey Noyes, Oneida Robert Owen, New Harmony Karl Marx Train cities, instant cities, walking cities Political, economic, social, cultural, intellectual, environmental, “history” Chapter Focus Questions What impact did the new 1840s & 1850s immigration have on American cities? Why did urbanization produce so many problems? What motivated the social reformers of the period? [Were they benevolent helpers or dictatorial social controllers? Study several reform causes and discuss similarities and differences among them.] Abolitionism differed little from other reforms in its tactics, but the effects of antislavery activism were politically explosive. Why was this so? Ralph Waldo Emerson 1803-1882 -- Transcendentalist philosopher Nathaniel Hawthorne 1804-1864 The Scarlet Letter [1850] “The Wayside” at Concord, MA – home to both Hawthorne and Louisa May Alcott Henry David Thoreau 1817-1862 Walden, 1854 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow 1807-1882 -- Paul Revere’s Ride, The Song of Hiawatha, Evangeline Longfellow’s home in Cambridge, MA – taught Harvard modern languages, 1836-1854 Noah Webster 1758-1843 -- an ardent Federalist, published 1806 dictionary Horace Mann 1796-1859 -- Sec. of the MA state board of education, Rep. 1849-1853 A page from McGuffey’s Reader, first published by William Holmes McGuffey 1800-1873 [6 editions, 122 million copies, used until the 1920s] Prudence Crandell 1803-1889 -- Quaker school teacher who admitted an African American to her Canterbury, Conn. school – Conn passed new law in 1833 making this Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet 1787-1851 Started first free school for education of the deaf in Philadelphia in 1817 Edward Miner Gallaudet 1837-1918 – Son of Thomas Gallaudet, opened Washington, D.C. school for the deaf NY Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb in early 19th century [LA public hospital of 1930s was free for the poor!] Samuel Gridley Howe 1801-1876 -- Ran New England Asylum for the Blind for 44 years Dorothea Lynde Dix 1802-1887 -- Between 1838 & Civil War lobbied to improve conditions for insane – led to new hospitals and asylums in 15 states and Canada NY Lunatic Asylum –cure insane through kind treatment and healthful living conditions Robert Mills 1781-1855 -- South Carolina architect – designed asylum with private rooms for each inmate, fresh air circulation “Widows’ and Orphans’ Asylum in Philadelphia -- this publicly funded institution replaced privately funded ones Auburn, NY State Prison -- belief that the environment, not character created criminals University of Virginia at Charlottesville, founded in 1819 – an “academic village” Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky -- founded in 1780 “Slab Hall” or “Cincinnati Hall,” one of 1st dormitory buildings at Oberlin College, built in 1835 [Founded when Lane Seminary in Cincinnati refused to endorse the immediate abolition of slavery -- Theodore Dwight Weld led students to form their own college!] Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, 1836 -- first college for the higher education of “daughters” in South Hadley, MA Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution, founded in 1846 with a legacy from James Smithsonian of London One of earliest US Sunday schools in Beverly, MA -- new focus on children, their education, and “Republican motherhood” Charles Grandison Finney 1792-1875 – Presbyterian minister by 21, then became Congregationalist and revivalist – president of Oberlin College, 1851-1865 William Ellery Channing 1780-1842 -- father of American Unitarianism in 1819 – humanitarianism, rationality, and religious toleration – influenced Transcendentalists Robert Owen 1771-1858 -- British social reformer, established several model industrial communities including New Harmony, Indiana -- environment creates the human society which was perfectible through cooperation “A Bird’s Eye view of one of the new communities at New Harmony, Indiana, an association of two thousand persons formed upon the principles advocated by Robert Owen.” Founded in 1825 and dissolved in 1827, its residents founded the first US kindergarten, the first free public school, and the first free public library. Drawing of the plan created by architect Stedman Whitwell in 1828 Ann Lee’s “Shakers” – United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing -- 1774 in NY, celibacy, 6,000 members in 1830s Shaker Village of Alfred, Maine – millenium sect with communal life Oneida, NY community’s business office, founded by John Humphrey Noyes in 1848 – corporate marriage of all members to each other – communal care of children Iowa’s Amana Community, founded in 1855 Joseph Smith 1805-1844, founded Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints based on visions from God at Palmyra, NY in 1827 and published in Book of Mormon in 1829 Nauvoo, Illinois Mormon Temple -- burned by mob, anti-polygamists and anticommunally owned property Brigham Young 1801-1877 Mormons emigrating to Utah in 1847 Salt Lake City in 1855 Arthur Tappan 1786-1865 -- he and brother Lewis were NY evangelicals and wealthy silk merchants – helped fund American Anti-Slavery Society [he became the president], The Liberator, Lane Seminary, and Oberlin College Theodore Dwight Weld 1803-1895 -- a disciple of Finney, attempted to radicalize the Lane Theological Seminary – married Angelina Emily Grimke [1805-1879] in 1838 – his 1839 American Slavery as it Is was a source for Harriet Beecher Stowe Sarah Moore Grimke 1792-1873 – to Philadelphia from Charleston to protest slavery James G. Birney 1792-1857 -- founded Kentucky Anti-Slavery Society, co-founder of 1840 Liberty Party, its candidate for president in 1840 and 1844 William Lloyd Garrison 1805-1879 -- first militant white voice for immediate abolition [Free African Americans had opposed colonization in Africa and gradual emancipation] Masthead of William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper on August 13, 1831 Issue #1 on Jan. 1, 1831 reads: “I am in earnest – I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch – AND I WILL BE HEARD.” Frederick Douglass 1817-1895 -- escaped from slavery in 1838, autobiography in 1845, The North Star newspaper Elijah P. Lovejoy 1802-1837 – Nov. 7, 1837 in Alton, Illinois, his 4th press was destroyed and he was killed by proslavery men from Missouri Wendell Phillips 1811-1884 -- Boston Common speech Lucretia Mott 1793-1880 -- active in antislavery movement, Society of Friends, denied opportunity to attend 1840 World’s Anti-slavery Convention in London as woman, women’s rights leader Susan B. Anthony 1820-1906 [standing] and Elizabeth Cady Stanton 1815-1902 -- first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, NY in 1848 Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s home in Seneca Falls, NY [after 1905 restoration] Sarah Josepha Hale 1788-1879 – accepted “separate spheres” instead of political equality – 40 year editor of pioneer women’s magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book and cofounder of Vassar College Jane Addams 1860 - 1935 Chronology 1820s 1825 1827 1830 1833 1834 1837 1840s 1843 1844 1845 1848 Shaker colonies grow New Harmony Public school movement begins in Mass. (Horace Mann) Joseph Smith founds Church of Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) American Anti-Slavery Society founded by Garrison and Theodore Weld First Female Moral Reform Society (NY); National Trades Union Sarah and Angela Grimké – equality of races and sexes Boston and NY City complete public water systems Dorothea Dix spearheads asylum reform movement Joseph Smith killed; Mormon migration to Great Salt Lake in 1846 NY creates city police force Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls; John Noyes founds Oneida Community Recommended Degler, Carl N. At Odds: Women and the Family in America from the Revolution to the Present. (1980) Douglass, Frederick. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. (1845) Gutman, Herbert G. Work, Culture, & Society in Industrializing America: Essays in American Working-Class History. (1976) Handlin, Oscar. Boston’s Immigrants: A Study in Acculturation. (Revised 1959) and The Uprooted (1951) Lerner, Gerda. The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition. (1967) Nash, Gary B. Forging Freedom: Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720-1840. (1988) Mintz, Steven. Moralists and Modernizers: America’s Pre-Civil War Reformers. (1995) Pessen, Edward. Most Uncommon Jacksonians: The Radical Leaders of the Early Labor Movement. (1967) Sklar, Kathryn. Catharine Beecher: A Study in American Domesticity. (1973) A: Seneca Falls In 1848, almost 300 male and female reformers gathered for the Seneca Falls women’s rights convention. The participants passed resolutions calling for a wide range of rights for women, including the right to vote. Women’s rights was just one of many reform movements of the time that emerged to respond to societal issues raised by the dislocations of the market revolution B: Urban America The Growth of Cities in Perspective The market revolution increased the size cities, beginning in the seaports. With one exception, the largest cities in 1800 kept that status in 1850. Preindustrial cities were geographically small "walking cities" that fostered the mingling of social classes. Due to the market revolution, urban population rapidly grew between 1820 and 1860. Tremendous amounts of commerce passed through the older port cities. “Instant” cities like Chicago sprang up at critical transportation points in the interior. Patterns of Immigration Immigration was a key part of urban growth. Beginning in 1830 immigration soared, particularly in the North. Immigrants came largely from Ireland, Germany, and China. Irish, German, and Chinese Immigration Irish Immigration: (1) Potato famine, (2) settlement in east, (3) discrimination and poor working and living conditions. Chinese Immigration: (1) Gold Rush, (2) discrimination. German immigration: • (1) Market forces stimulated immigration, (2)settled in the Midwest. All three groups developed strong ethnic communities. Irish and German Immigrant Employment in New York City,1855 Irish immigrants were clustered in laborer and domestic jobs. German immigrants were clustered in skilled trades. Class Structure and Living Patterns The gap between rich and poor grew rapidly. Economic class was reflected by residence as: poor people (nearly 70 percent of the city) lived in cheap rented housing middle-class residents (25-30 percent) lived in more comfortable homes very rich (about 3 percent) built mansions and large town houses. Health, Sanitation and Residence In the early nineteenth century, cities had no adequate sanitation systems, leading to disease epidemics. The introduction of sanitation systems furthered residential segregation as: the wealthy clustered in neighborhoods with these services the middle-class moved to new suburban areas the poor became packed in dirty and crime-ridden slums Ethnic Neighborhoods and Urban Popular Culture Irish and German immigrants created ethnic enclaves to maintain cultural tradition and institutions. A new urban popular culture emerged that challenged middle class respectability centering around: the tavern theaters the penny press Civic Order Americans grew concerned that the cities would become centers of disorder. Prosperous classes were frightened by the urban poor and by workingclass rowdyism. Cities began to hire more city watchmen and to create police forces to keep order. Urban riots did break out, frequently against Catholics and African Americans. The Urban Life of Free African Americans About half of the nation’s free African Americans lived in the North, mainly in cities, where they encountered: residential segregation job discrimination segregated public schools limits on their civil rights Free African Americans formed community support networks, newspapers, and churches. The economic prospects of African American men deteriorated. Free African Americans engaged in antislavery activities, but were frequent targets of urban violence. C: The Labor Movement and Urban Politics The Tradition and Decline of Artisanal Politics American cities had long been centers of organized artisans and skilled workers. Worker associations, parades and celebrations were parts of the urban community. By the 1830s, the skilled craft workers were being undercut by industrialization. Workers’ associations became increasingly classconscious turning to fellow laborers for support. Initially, urban worker protest against change focused on party politics, including the short-lived Workingmen's Party. Both major parties tried to woo the votes of organized workers. The Union Movement Workers organized trade unions and formed city-wide “General Trades Unions.” The local groups then organized the National Trades Union. The trade union movement was met with hostility and most collapsed during the Panic of 1837. Early unions included only skilled white workers. Big-City Machines Competition for the votes of workers shaped urban politics. Big-city machines arose reflecting the class structure of the fat-growing cities. The machines cultivated feelings of community by: appealing directly for working-class votes through mass organizational activities creating organizations that met basic needs of the urban poor The machines also had a tight organizational structure headed by bosses who traded loyalty and votes for political jobs and services, leading to charges of corruption. D: Social Reform Movements Evangelism, Reform and Social Control Middle-class Americans responded to the dislocations of the market revolution by promoting various reform campaigns. Evangelical religion drove the reform spirit forward. Reformers recognized that: traditional small-scale methods of reform no longer worked the need was for larger-scale institutions The doctrine of perfectionism combined with a basic belief in the goodness of people and moralistic dogmatism characterized reform. Regional and national reform organizations emerged from local projects to deal with various social problems. Reformers mixed political and social activities and tended to seek to use the power of the state to promote their ends. Education and Women Teachers Educational reformers changed the traditional ways of educating children by: no longer viewing children seen as sinners whose wills had to be broken seeing children innocents who needed gentle nurturing. The work of Horace Mann and others led to taxsupported compulsory public schools. Women were seen as more nurturing and encouraged to become teachers, creating the first real career opportunity for women. The Saloon and Reform Reformers attacked the immigrant saloon for promoting drinking and being centers for organizing political machines. The Drunkard’s Progress Temperance tracts painted a lurid picture of the effects of alcohol. “The Drunkard’s Progress, from the first glass to the grave.” 1846 lithograph by Nathaniel Currier Temperance Middle-class reformers sought to change Americans’ drinking of alcohol habits. Temperance was seen as a panacea for all social problems. Prompted by the Panic of 1837, the working class joined the temperance crusade. By the mid-1840s alcohol consumption had been cut in half. Moral Reform, Asylums, and Prisons Reformers also attacked prostitution by organizing charity for poor women and through tougher criminal penalties but had little success. The asylum movement promoted humane treatment of the insane and criminals, but prison often failed to meet their purposes. Reform Movements in the Burned-Over District The region of New York most changed by the Erie Canal was a fertile ground for religious and reform movements, earning the name Burned-Over District. The reform movements originating or thriving there included: the Mormon Church utopian groups like the Millerites and Fourierites antislavery sentiment the women's rights movement; Utopianism Amid the reform fervor some people formed utopian communities. Religious utopians like the Millerites and Shakers saw an apocalyptic end of history. The Shakers also practiced celibacy amid a fellowship of equality. Conversely, John Humphrey Noyes’s Oneida Community practiced “complex marriage.” New Harmony and the various Fourier-inspired communities unsuccessfully attempted a kind of socialism. Mormonism The most successful communitarian movement was Mormonism. Founded by Joseph Smith and harassed by others, the Mormons migrated to Utah. E: Antislavery and Abolitionism Abolition Before 1820 Various antislavery steps had been taken prior to the 1820s. But they had not addressed the continuing reality of Southern slavery. The ineffective American Colonization Society resettled a small number of free African Americans in Africa where they founded Liberia. African Americans’ Fight Against Slavery Free African Americans rejected colonization. They founded abolitionist societies that: demanded equal treatment demanded an end to slavery encouraged slave rebellions. Abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison headed the bestknown group of antislavery reformers. Garrison denounced all compromise (including political action and the Constitution) and called for immediate emancipation on moral grounds. The American Anti-Slavery Society drew on the style of religious revivalists as they tried to confront slaveholders and lead them to repentance. Abolitionist mailed over a million pieces of propaganda that led to a crackdown by southern states and a stifling of dissent. Several abolitionists were violently attacked and one was killed. Abolitionism and Politics Abolition began as a social movement but soon became a national political issue. Abolitionists inundated Congress with petitions calling for abolition in the District of Columbia. Congress imposed a “gag rule” tabling all such petitions, but it was repealed in1844. [JQA’s position in H of R] Abolitionist unity splintered along racial and political lines. White abolitionists (other than Garrisonians) founded the Liberty Party. F: The Women’s Rights Movement Women and Reform Women were active members of all reform societies and even formed their own antislavery organizations. Sarah and Angelina Grimke left their South Carolina home and traveled north to denounce slavery, becoming the first female public speakers in American history. Two decades of activity culminated with the Seneca Falls women’s rights convention in 1848 and the beginnings of the women’s rights movement. Historians have only recently acknowledged the central role women played in the various reform movements of this era.