IQ testing time to 3, handout June 13

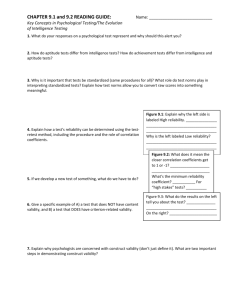

advertisement

IQ testing: time to move on? Jenny Webb Consultant Clinical Psychologist jenny.webb@agencyandaccess.co.uk An early question ... “IQ as a score is inherently meaningless and not infrequently misleading as well. ‘IQ’ has outlived whatever usefulness it may once have had and should be discarded ... Combined scores such as the ‘Index Scores’ in Wechsler batteries may also obscure important information obtainable only by examining discrete scores” (Lezak et al, 2004:22) Mapping the territory History Reliability IQ testing Validity Alternatives Purpose Context The First World War • Wechsler was an army test administrator • Used Alpha, Beta & Army Performance tests in selection of recruits • 1.7 M men tested • 1916 Terman devised IQ score, based on ratio of mental to chronological age And after the war ... • Post-war use of tests in schools and acceptance of idea of fixed, inherited intelligence, in both US and Britain • Wechsler repackaged army tests for psychiatric patients in asylums, with new method of computing IQ scores • The birth of the IQ test as we now know it in 1939 with publication of the Wechsler-Bellevue But what was being measured? • “to demand ... that one who would measure intelligence should first present a complete definition of it, is quite unreasonable ... Electrical currents were measured long before their nature was well understood” (Terman, 1916) • “Intelligence is what the intelligence tests test” (Boring, 1929) • “Statistical norms and values become incorporated within the very texture of conceptions of what is today’s psychological reality.” (Rose, 1991) Wechsler’s concept of intelligence • 1944: The “capacity of the individual to act purposefully, to think rationally, and to deal effectively with his environment” • 1981: “an overall competency or global capacity” “Multi-faceted and multi-determined” “A function of the personality as a whole – responsive to factors other than cognitive abilities” (‘conative’ variables) • (what IQ tests measure) “is not something which can be expressed by one single factor alone, say ‘g’” (Wechsler, quoted in Tulsky et al, 2003) And in the WAIS-IV ... What it does ... • Validity established by extent to which results correlate with those of earlier intelligence tests, and correlations between result on subtests which comprise the four indexes What it says ... • Validity refers to the degree to which evidence supports the interpretation of test scores for the intended purpose ... As a result, examination of a test’s validity requires an evaluative judgement by the tester • Evolving conceptualizations of validity no longer speak of different types of validity but speak instead of different types of validity evidence, all in service of providing information relevant to specific intended interpretation of test score. (American Educational Research Association, in WAIS-IV Manual, 2008) What does DSM-V say? • The definition of LD is largely unchanged • But a proposal has been made to locate it within a group of conditions labelled ‘Neurodevelopmental Disorders’. ‘Mild mental retardation’ is to be placed at one end of a single spectrum that includes people with autistic spectrum disorders (Andrews et al, 2009). • Very few references taken from the LD literature What does the BPS say? • In its response, the BPS recognised that the diagnostic systems for mental illness “fall short of the criteria for legitimate medical diagnoses”. • But as far as LD is concerned, the BPS said that:“the use of diagnostic labels has greater validity, both on theoretical and empirical grounds” (BPS, 2011). • No changes were suggested What does it mean to ask about construct validity? • Based on the assumptions that: – the construct ‘really’ exists – it forms part of a theoretical network of propositions which yield falsifiable predictions (Boyle, 2001; Popper, 1963) • These assumptions are problematic, in the case of both intelligence, and hence with learning disability, which piggy-backs on the construct of intelligence Theories of intelligence and LD • The definition of intelligence is still disputed. • Psychiatric diagnoses in general do not meet the criteria of construct validity given above • The definition of LD includes reference to adaptive function, which is one of the behaviours that the intelligence test seeks to predict • Poor reliability implies absence of validity Reliability • Poor reliability applies not just to cut-off point but to standardisation in general including: – – – – Method of recruitment of standardisation sample Exclusion criteria Very low numbers of people with LD in each age group Assumption of normal curve, which probably does not apply in the low IQ range – Irregulaties in test administration by clinicians – Arbitrary changes in test content – Test items not standardised on PWLD Ecological validity • Intelligence as measure by IQ correlates with academic performance, occupational achievement (Sternberg et al, 2001; Dickerson Mayes et al, 2009), and survival into old age (Deary et al, 2008) • But relationship to measures of adaptive behaviour only moderate (Whitaker, 2003) • IQ in PWLD a less significant contributor to self-determination than opportunity to make choices (Wehmeyer & Garner, 2003) Historical relativity • We cannot assume that ‘learning disability’ equates with earlier labels for people seen as having cognitive impairments (Goodey, 2011). Abilities needed to function in different eras vary • The medicalisation of LD only occurred in the 19th Century with the institutional ascendance of the medical profession • There has also always been a political agenda, beginning with concern about property rights in Middle Ages • From 1961-1972 the definition of LD given by the AAMR specified an IQ of one SD below the mean (ie IQ 85). In 1973 this was revised to raise the cut-off point to two SDs below the mean (ie IQ 70) Cultural relativity ICD10 Diagnostic Criteria for Research • Detailed diagnostic criteria cannot be specified for mental retardation, since ‘low cognitive ability and diminished social competence, are profoundly affected by social and cultural influences’ (WHO, 1993: F70-7). • Eg – Kenya: intelligence defined as “the ability to do without being told what needed to be done around the homestead” – Brazilian street children: may fail maths at school, but run successful street businesses (Sternberg, 2001 on ‘Practical Intelligence’) How is the WAIS used? 1. As a way of locating the person in relation to the hypothesised normal distribution of intelligence. They may then be labelled as ‘having’ or ‘not having’ a LD and services may be allocated on this basis. 2. As a test of discrete cognitive functions eg verbal expression, visuo-spatial ability, though most of the tests involve multiple cognitive functions. Alternative models of cognitive assessment • Neuropsychological (localisation/functional interconnections) (Lezak et al, 2004; Luria, 1970) • Developmental (Hogg & Sebba, 1986) • Developmental cognitive neuropsychology (Karmiloff-Smith, 1995) • Capacity to learn (Feuerstein R & Rand Y, 1998) • Environmental demands/supports (AAMR, 1992) • Central role of non-cognitive variables (Raven & Raven, 2008) Social implications • Intelligence testing has always served a social function, at its worst associated with labelling, stigma, discrimination, eugenic solutions, racism, imprisonment and control of reproduction eg: “intelligence tests ...will ultimately result in curtailing the reproduction of feeblemindedness and the elimination of an enormous amount of crime, pauperism, and industrial inefficiency” (Terman, quoted in Minton, 1988). • In my experience IQ score is currently used as way of rationing services. ‘Mild’ LD is equated with low risk or mild problem. This is regardless of the actual level of risk the person faces. • A moral dimension attaches to this discrimination, so that certain people are seen as not only ineligible but undeserving of services. This is reminiscent of Victorian distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. Stephen, aged 25 • Prospective father • Born with cerebral palsy, and has hearing impairment • Has a troubled history • Is very chatty and appears capable • Refused service from both LD SS and Locality SS team • ABAS results: – General Adaptive Composite 68-74 (per. rank 3) Stephen’s WAIS results Similarities Digit Span Vocabulary Arithmetic Information Scaled Score 4 6 4 3 8 Scaled Score Block Design 6 Matrix Reasoning 6 Symbol Search 9 Coding 4 Composite Score Verbal Comprehension Index 69-81 Perceptual Reasoning 72-84 Working Memory 64-78 Processing Speed 75-91 Full Scale IQ 68-76 Percentile Rank 4 6 2 10 3 Stephen’s OT AMPS Assessment (Assessment of Motor & Process Skills) Standard score *ADL Motor ^ADL Process 51 <45 Percentile rank < 1.0 < 1.0 *Observable, goal-directed actions enabling a person to move themselves or task objects ^Observable, goal-directed actions that are used to logically organise & adapt behaviour in order to complete a task Stephen’s OT Report Difficulties in eg: • Positioning body, reaching for objects, manipulating & carrying objects, coordination, walking • Distraction, carelessness, organisation, anticipating change & responding to problems, learning from experience Conclusions: safety issues; limited potential to learn new skills; need for compensatory strategies Stephen’s SALT Report, after initial visit • • • • Tangential conversation Reluctant to say he does not understand Literal interpretation Difficulty in understanding negatives, prepositions, reversible sentences, comparatives, plurals, complex sentences • Unable to tell the time • Acquiescent, leading to frustration & anger How should we report on Stephen’s LD assessment? • Say he has not ‘got’ a learning disability? • Produce a long and nuanced report? • Fiddle the results? A different direction? • Leave definition of ID to the psychiatrists and redefine LD in a clinically meaningful way • There are several suggestions which we can draw on. These mostly include the concepts of: – age of onset – cognitive function – adaptive function – risk – vulnerability Alternative definitions of LD • Flynn (2000) suggests the use of direct tests of impaired adaptive behaviour to assess intellectual disability. • Greenspan & Switzky (2006) suggest defining ID in terms of deficits of conceptual, practical and social intelligence that result in a need for supports in order to succeed in culturally relevant roles • Greenspan et al (2011) suggest that impairments are demonstrated by the person’s history of academic, practical and social risk • Whitaker’s (2008) definition links competence, environmental demands, intellect, risk and distress. • Raven & Raven (2008) suggest finding out what interests the person, and then how good they are at the cognitive functions needed for this task. Another suggestion ... “The learning disabled are those people who, due to cognitive deficits beginning at birth or during childhood, are unable to fulfil social roles in a way that is expected in a particular society at a particular time, and hence are considered to be at risk, practically, physically, socially or emotionally.” (Webb, 2014) Link between LD definition, formulation and intervention BPS Good Practice Guidelines on Formulation: recent moves within Clinical Psychology to begin to "develop coherent, credible alternative forms of categorisation which are based on psychological theory and which have direct implications for both aetiology and intervention" (BPS, 2011) Whatever we decide ... I hope we will not collude in withholding of services to very vulnerable people by continuing to use a definition of learning disability which is theoretically & methodologically unsound. I hope that today we can begin to seek a definition which is both meaningful and helpful to our very vulnerable clients Selected references re definition BPS (June 2011) Response to American Psychiatric Association: DSM-V Development Flynn J R (2000) The hidden history of IQ and special education Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 6, 1, 191-8 Greenspan S & Switzky N (2006) What is Mental Retardation? Ideas for an evolving disability in the 21st Century Washington DC: AAMR Greenspan et al (2011) Intelligence involves risk-awareness and intellectual disability involves risk-unawareness: implications of a theory of common sense Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 36, 246-57 Raven J & Raven J eds (2008) The Uses & Abuses of Intelligence NY: Royal Fireworks Press Webb J (2014) A guide to psychological understanding of people with learning disabilities: eight domains and three stories London: Routledge Whitaker S (2008) Intellectual disability: a concept in need of revision? British Journal of Developmental Disabilities 54(1) 3-9 Other references Andrews G et al (2009) Exploring the feasibility of a meta-structure for DSMV and 1CD11: could it improve utility and validity? Psychological Medicine 39, 1992-2000 Boyle M (2000) Schizophrenia: a Scientific Delusion? BPS (2011) Good Practice Guidelines on the Use of Psychological Formulation Leicester: BPS Feuerstein R & Rand Y (1998) Don’t Accept Me As I Am Arlington Heights: Skylight Flynn J R (2000) The hidden history of IQ and special education Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 6, 1, 191-8 Goodey CF (2011) A History of Intelligence and Intellectual Disability: the shaping of Psychology in early modern Europe Farnham: Ashgate Luria A R (1970) The functional organisation of the brain Scientific American 222 (3) 66-78 Other references cont’d McKenzie K, Murray G C &Wright J (2004) Adaptations and accommodations: the use of the WAISIII with PWLD Clinical Psychology 43, 23-6 Murdoch S (2007) IQ testing: the brilliant idea that failed London: Duckworth Overlook Popper K (1963) Conjectures and refutations London: Routledge Russell E W (2010) The ‘obsolescence’ of assessment procedures Applied Neuropsychology 17, 60-67 Sternberg R J et al (2001) The predictive value of IQ Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 457(1), 1-41 Wehmeyer M L & Garner N W (2003) The impact of personal characteristics of people with intellectual and developmental disability on self-determination and autonomous functioning Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 16, 255-65