document

advertisement

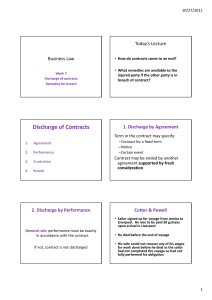

DISCHARGE OF A CONTRACT & REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT Objectives: 1. Discharge of a Contract. 2. Remedies for Breach of Contract. 1 Discharge of a Contract 1. When a contract is discharged, the parties to the agreement are freed from their contractual obligations. 2. A contract can be discharged by: i. Agreement. ii. Performance. iii. Frustration. iv. Breach. 2 3. Discharge by Agreement i. A contact is made by agreement so can be ended by agreement. ii. Discharge by agreement is usually provided for in the contract via a term allowing for discharge by the: i. ii. iii. passage of a fixed period of time. occurrence of a particular event. parties giving notice of their intention to discharge. Where there is no such provision, another contract would be required to discharge the parties from their original obligations. 3 Discharge by Performance 4. i. This occurs where the parties perform their obligations under the contract (most common method). ii. Generally, discharge by performance requires COMPLETE and EXACT performance by the parties of ALL their contractual obligations. iii. Cutter v Powell [1795] For the injustice the application of this general rule can cause. 4 iv. Complete and exact performance may not be necessary if any one of the following can be proved: i. The contact is divisible – Taylor v Webb [1937] ii. The contract is capable of being fulfilled by substantial performance – Hoenig v Isaacs [1952]. iii. Performance has been prevented by the other party. iv. Partial performance has been accepted by the other party. 5 5. Discharge by Frustration i. This occurs where it is impossible for the parties to perform their contractual obligations. ii. A contract will be discharged by reason of frustration in the following circumstances: i. Destruction of contractual subject matter has occurred. Taylor v Caldwell [1863]. ii. Government interference, or supervening illegality prevents performance. Re Shipton, Anderson & Co [1915]. 6 iii. A particular event, which was the sole reason for the contract, fails to take place. Krell v Henry [1903] but note Herne Bay Steamboat Co v Hutton [1903]. iv. The commercial purpose of the contract no longer exists. Jackson v Union Marine Insurance Co [1874]. v. One of the parties dies or becomes otherwise incapacitated. Condor v Barron Knights [1966] 7 iii. However a contract will NOT be discharged by reason of frustration in the following circumstances: i. The parties have made express provision in the contract for the event which has occurred. ii. The frustrating event was self-induced i.e. could have been avoided. Maritime National Fish Ltd v Ocean Trawlers Ltd [1935]. iii. An alternative method of performance is still possible. 8 iv. The contract simply becomes more expensive to perform i.e. cannot use frustration to escape from a bad bargain. Davis Contractors v Fareham UDC [1956]. iv. Effect of Frustration i. Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. The position is as follows in relation to a contract discharged by reason of frustration: i. Any money paid is recoverable. ii. Any money due to be paid ceases to be payable. 9 iii. The courts may allow the parties to: i. Cover expenses incurred from any money received; or ii. Recover those expenses from money due to be paid before the frustrating event. Expenses cannot be retained or recovered if no money was paid or due to be paid before the frustrating event. ii. Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 does NOT apply to contracts: i. ii. For the carriage of goods by sea. Of insurance and / or perishable goods. 10 6. Discharge by Breach i. One of the parties fails to comply with its contractual obligations. Breach of contract may occur in three ways: i. Prior to performing contractual obligations, one of the parties states that it will not perform its obligations. ii. One of the parties fails to perform obligations. iii. One of the parties performs its contractual obligations defectively. 11 ii. Effect of Breach i. All three types of breaches will allow innocent party to sue for damages. ii. In the following instances, in addition to damages, the innocent party would also be able to treat the contract as discharged and therefore refuse either to (i) perform their part of the contract or (ii) accept further performance from the party in breach: i. Where the other party has repudiated the contract before performance is due or fully complete; ii. Where the other party has committed a fundamental breach of contract. 12 iii. Anticipatory Breach i. Arises when one of the parties, prior to the actual date of performance, demonstrates an intention not to perform their contractual obligations. ii. Intention can be demonstrated expressly or impliedly: i. Expressly – One of the parties actually states that they will not perform their contractual obligations. 13 ii. Impliedly – One of the parties carries out some act which makes performance impossible. 14 Remedies for Breach of Contract 1. Main remedies are: i. Damages. ii. Quantum Meruit. iii. Specific Performance. iv. Injunction. 2. Damages i. Amounts to monetary compensation. Lord Diplock in Photo Productions Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [1980]. 15 ii. Two tests used to determine a claim for damages: i. Remoteness of damage. ii. Measure of damages. iii. Remoteness of Damages i. Damages will only be awarded in respect of losses which: i. Are the natural consequence of any breach; or which ii. Both parties would reasonably have contemplated when the contract was made as a probable result of any 16 ii. Hadley v Baxendale [1854]. iii. Victoria Laundry Ltd v Newham Industries Ltd [1949]. iv. Measure of Damages i. Aim is to put injured party in the same position they would have been in, had the contract been properly performed. ii. So amount of damages awarded can never be greater than actual loss suffered. Aim is not to punish party in breach. 17 iii. Value of damages decided upon by reference to following principles: i. Market Rule. i. Damages will be valued at market price of goods in question. ii. Duty to Mitigate/Minimise Losses. i. Injured party under a duty to take all reasonable steps to minimise its loss. Pilkington v Wood [1953] iii. Non-Pecuniary Loss. i. Non-financial loss can be recovered. Jarvis v Swan Tours Ltd [1973]. 18 v. Liquidated Damages and Penalties i. Liquidated Damages i. Where parties incorporate provision(s) in contract agreeing the amount of damages that will be paid in the event of any breach. ii. Only enforced by courts if damages agreed upon represent a genuine pre-estimate of loss. ii. Penalties i. If courts adjudge damages do NOT represent a genuine pre-estimate but instead a penalty against the party in breach, courts will ignore agreed provision and award damages normally. 19 3. Quantum Meruit i. A party may occasionally claim for payment on a quantum meruit basis, i.e. for work done, paying the amount that is deserved. ii. Can only be claimed in the following circumstances: i. If the other prevented completion of the contract. ii. If work has been done and accepted under a void or partially performed contract. iii. If the contract did not expressly provide what the remuneration should be. 20 4. Specific Performance i. Party in breach instructed to complete their part of the contract, providing following rules adhered to: Only granted where damages inadequate. ii. Will not be granted if courts cannot supervise enforcement. iii. Specific performance an equitable discretionary remedy, so will not be granted for instance where plaintiff acted improperly. Injunction i. Court order directing a party not to break its contractual obligations. i. 5. 21 6. Time Limits on Remedies i. Limitation Act 1980. ii. A simple contract (i.e. not made by deed) cannot be sued upon after six years have expired from date of breach. (S.5) iii. Three years if claim for personal injury. iv. These limits do not apply to the equitable remedies of injunction and specific performance. These remedies lost more quickly through concept of “unreasonable delay.” 22