Class #5 - 10/7/2015

advertisement

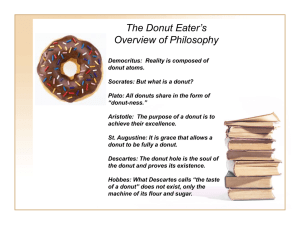

Philosophy 1010 Class #5 Turn in your Argument Critique Hand back & Discuss: 1) Socratic Dialogue, 2) Logic Homework re-do Midterm Exam: Next Week The Traditional Western View • The Prevalent View Regarding the Nature of Man Makes Four Basic Claims: 1) That the self is conscious and has a purpose 2) That the self is distinct from the body, but somehow is related. 3) That the self endures through time. 4) That the self has an independent existence from other selves Chapter 2 On Human Nature: A Metaphysical Study • Video (continue at 15:15): What is Human Nature? (Worksheet with answers on QUIA) The Traditional Western View • The Prevalent View Regarding the Nature of Man Makes Four Basic Claims: 1) That the self is conscious and has a purpose 2) That the self is distinct from the body, but somehow is related. 3) That the self endures through time. 4) That the self has an independent existence from other selves The Dualist View of Human Nature • The Dualist View is an ancient view that can be traced back to Plato and the Traditional Rationalist View of Human Nature. • A developed, systematic view of Dualism was best expressed by Rene Descartes (1596-1650). • Descartes argues that he can imagine his self without a body, thus the self is not the body. We cannot think of the self without thought which is immaterial. Thus, the mind and body must be distinct. • Descartes further argues that the mind or “soul” is the essential form of the self and could exist without the body. • I think, therefore I am. The Mind-Body Problem • So how can the mind as a non-physical entity cause the physical body to act and how can the physical body cause changes in the state of the mind? • Can the mind add energy or force to the physical world? But that is exactly what seems to happen when I decide to move my hand and then move it. • How can a physical body alter a state of consciousness or thought? But that is exactly what seems to happen when a fly buzzes near my head and I become annoyed. Cartesian Dualism on the Mind-Body Problem • Descartes suggested that the mind/body interacts through the pineal gland, a small gland near the brain by being so small that an immaterial mind could move it. • But the problem still seems to remain! No matter how small a physical object is, it is of course still a physical object. Responses to Cartesian Dualism • Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) denied that the mind and body actually do interact. They only appear to do so. • Leibniz argued that the mind and the body operate in parallel universes like synchronized clocks. • Nicholas Malebranche (1683-1715) argued that such a synchronism could not occur by coincidence. Only by the constant act of God could the two worlds be kept parallel. Materialism • Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) rejects Cartesian dualism claiming that Descartes Mind/Body problem itself refutes dualism. • Since mind and body cannot interact, they cannot both exist within human nature. • There can only be one realm of human nature and that is the material world. • All human activities, including the mental, can be explained on the paradigm of a machine. Materialism • Hobbes was reductionist in that he believed that one kind of purported reality (the mind) could be understood entirely in terms of another (matter). • New scientific techniques of observation and measurement being used by Galileo, Kepler, and Copernicus were making giant strides in understanding the universe. • The spirit of his century suggested to Hobbes that all reality would be explained in time in terms only of the observable and the measurable. • Hobbes himself was unable to explain any mental processes in terms of the physical. • Perhaps motivating Hobbes’ view was basically his passionate faith in the advancement of science at the time. Chapter 2 On Human Nature: A Metaphysical Study • Video: Is Mind Distinct From the Body? (Hand out worksheet) The Traditional Western View • The Prevalent View Regarding the Nature of Man Makes Four Basic Claims: 1) That the self is conscious and has a purpose 2) That the self is distinct from the body, but somehow is related. 3) That the self endures through time. 4) That the self has an independent existence from other selves Is There An Enduring Self? • Descartes argues that the enduring self is the soul, an enduring immaterial being or existence. • John Locke (1632-1704) says that the enduring self is a based only on our having continuous memory. • Buddhism asserts that nothing in the universe, particularly the self, remains the same from one moment to the next. • David Hume (1711-1776) also denies that there is an enduring self. He argues that only what we perceive exists and that we never perceive an enduring self, only a constant flow of perceptions. The Traditional Western View • The Prevalent View Regarding the Nature of Man Makes Four Basic Claims: 1) That the self is conscious and has a purpose 2) That the self is distinct from the body, but somehow is related. 3) That the self endures through time. 4) That the self has an independent existence from other selves Is the Self Independent or Relational? • Descartes argues that the self exists independently of others and the independent self can judge the truth about what is. • Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) suggests that the self is the ability to choose independently of others, and not being determined by conforming to others. Georg W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) proposes that the self is relational. A person is only free and independent if others recognize him or her to be so. • Charles Taylor (1931- ) argues that we depend on others for the very definition of what our real self is. Chapter 3 Reality and Being (a Metaphysical Study) *** Realism • Realism is the view that the real world exists independent of our language, our thoughts, our perceptions, or our beliefs about it. • Our common sense seems to demand of us that we believe in realism. • But how can we know that “our wonderful world is real?” Can we prove it? Or alternately, do we have evidence? Can we provide “reasons to believe” without “begging the question?” • And what does it even mean for our world to be “real?” If someone were to say that the world was NOT real, what would he mean? What would we understand that he was saying? What Is Reality? • For now, let us assume we are realists, that is, we believe in realism. So what is the reality we believe in? • Some might argue that reality is what we experience through our senses. • Or would you perhaps argue that reality consists of more than the material world? What about justice, mathematics, liberty, freedom, truth, beauty, space, time, and love? • Is language real? • Is God real? • Or the sub-atomic theoretical entities that physics asserts? Are they real? Metaphysics is the Study of What is Real • The most fundamental question in metaphysics may be: Is reality purely material or is there reality beyond the material? • We already discussed this question to some degree in terms of the mind/body problem, but now we will begin to look at this issue in a much broader scope. • We have already seen the materialism of Thomas Hobbes, particular in the context of the mind/body problem. Hobbes, however, argued for Materialism in a much broader sense. Early Views of Materialism The Pre-Socratics (460-360 B.C.E.) Democritus. Reality was composed of material atoms. Attributes of atoms are: solid, indivisible, indestructible, eternal, and uncreated. The composition of reality is atoms and empty space. The soul (or reason) consists of atoms. The Charvaka Philosophers of India (about 600 B.C.E) There is only one valid source of knowledge and that is what we perceive through our senses. What we perceive is physical and material. What we cannot know cannot exist. There are no gods, no soul. Plato and the World of the Forms Video Idealism & Plato’s Theory of Forms (a refutation of Materialism) Idealism & Plato’s Theory of Forms • The view that reality is primarily composed of ideas or thought rather than a material world is the doctrine known as Idealism. That is, an Idealist would say that a world of material objects containing no thought either could not exist or at the least would not be fully "real." • The earliest formulation of this view is given to us by Plato. • In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the world of shadows is representative of the material world and is not fully real. Plato’s Theory of Forms • What is the problem with which Plato is faced? • How can one live a happy and satisfying life in a contingent, changing world without there being some permanence on which one can rely? (The Ethical Problem) • Indeed, how can the world appear to be both permanent and changing all the time. (The Metaphysical Problem) • Plato observed that the world of the mind, the world of ideas, seems relatively unchanging. Justice, for example, does not seem to change from day to day, year to year. • On the other hand, the world of our perceptions change continuously. One rock is small, the next large, the next…? Plato’s Theory of Forms • To resolve this problem, Plato formalized the classic view of idealism in his doctrine of Forms. • In everyday language, a form is how we recognize what something is and unify our knowledge of objects. (e.g How do we say two objects of different size, color, etc. are both cars?) • Permanence comes from the world of forms or ideas with which we have access through reason. • In Plato’s view, all the particular entities we see as material objects are shadows of that reality. Behind each entity is a perfect form or ideal. Ideal forms are eternal and everlasting. Individual beings are imperfect. • e.g. Roundness is an ideal or form existing in a world different from physical basketballs. Individual basketballs participate or copy the form. Plato’s Theory of Forms • Forms are transcendent, that is they do not exist in space and time. That is why they are unchanging. • Forms are pure. They only represent a single character and are the perfect model of that property. • Material objects are a complex conglomeration of copies of multiple forms located in space and time. • Forms are the cause of all that exists in the world. What is the Essence of the Form of the Good? • Forms are the cause of all that exists in the world. Forms exist in a hierarchy with the Form of The Good being the highest form and thus is the first cause of all that exists. • Forms are the ultimate reality because they are more objective than material things which are subjective and vary in our perception of them. • For Socrates and Plato, the question “What is a thing?” is the question what is the essence of the thing? That is, the attempt is to identify what (presumably one) characteristic or property makes that thing what it is. What is the Essence of the Form of the Good? • Further, Plato compares the power of the Good to the power of the sun. The sun illuminates things and makes them visible to the eye. The absolute or perfect Good illuminates the things of the mind (forms) and makes them intelligible. • The Good sheds light on ideas but, the vision of the idea of the Good is, according to Plato, too much for human minds. • When Plato emphasizes The Good as the cause (I.e. an active agent) of essences, structures, and forms, as well as of knowledge, he seems to be invoking the idea of the Good as God. The Good as absolute order makes all intermediate forms or structures possible. Galileo & The Scientific Revolution Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642) played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. Galileo has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy", the "father of modern physics", the "father of science", and "the Father of Modern Science“ Galileo proposes that physics should be a “new science” based on methods of observation not just on the methods of reason. Thus, Galileo discovered many things: with his telescope, he first saw the moons of Jupiter and the mountains on the Moon; he determined the parabolic path of projectiles and calculated the law of free fall on the basis of experiment. Galileo & The Scientific Revolution He is known for defending and making popular the Copernican system, using the telescope to examine the heavens, inventing the microscope, dropping stones from towers and masts, playing with pendula and clocks, being the first ‘real’ experimental scientist, advocating the relativity of motion, and creating a mathematical physics. His major claim to fame probably comes from his trial by the Catholic Inquisition and his purported role as heroic rational, modern man in the subsequent history of the ‘warfare’ between science and religion. Towards A Modern View: Cartesian Dualism Descartes & Modern Philosophy René Descartes (1596–1650) was a creative mathematician of the first order, an important scientific thinker, and an original metaphysician. He offered a new vision of the natural world that continues to shape our thought today: a world of matter possessing a few fundamental properties and interacting according to a few universal laws. This natural world included an immaterial mind that, in human beings, was directly related to the brain. In many ways, Descartes established Philosophy as a modern endeavor and saw science and philosophy as intricately linked in their pursuit of knowledge. Yet, Descartes embraced the Scientific Revolution fundamentally differently that Galileo. Descartes claimed to possess a special method, which was variously exhibited in mathematics, natural philosophy, and metaphysics, and which, in the latter part of his life, included, or was supplemented by, a method of doubt. He was still fundamentally too much of a Rationalist in the traditions of Plato. This method of conducting science is quite contrary to the approach that was gaining sway with Galileo. Galileo proposed a methodology which did not first engage in a metaphysical search for first principles on which to base his science. Rationalism: Similarities Between Plato and Descartes Plato Justification is by reason rather than by the senses, not the world of the cave, which we find out about by sensory experience, and toward to world outside the cave, the world of Forms, which we discover by means of reason) The objects of knowledge, namely the Forms, are eternal, necessary, and unchanging (we want to find the permanent order that underlies the flux) The most important and basic knowledge is a priori (that is, not based on sensory information): this is true of knowledge of mathematics, of goodness, of justice, etc. Mathematics is a kind of model for the rest of knowledge. (Think of the perfect circle.) Descartes Ditto. The skeptical arguments of the first meditation show that the senses cannot be trusted. Later meditations suggest that a scientific picture of the world will not appeal to sensory properties but to (primarily) mathematical ones. We can have knowledge of the physical world. But the most basic objects of knowledge are general principles (e.g. the basic laws of physics), so the goal is still to penetrate behind the veil of appearance. We can gain some knowledge by means of the senses, but only after establishing a priori that they are more or less trustworthy; the most basic knowledge is a priori. Ditto: the metaphor of building knowledge up on firm foundations relies on a mathematical model. For Descartes, Galileo erred by “without having considered the first causes of nature, [he] has merely looked for the explanations of a few particular effects, and he has thereby built without foundations” But ultimately, it was Galileo (not Descartes) that pushed the Scientific Revolution forward. Materialism With the influence of Galileo, Hobbes develops his social philosophy on principles of geometry and natural science. • Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) rejects Cartesian dualism claiming that Descartes Mind/Body problem itself refutes dualism. • Since mind and body cannot interact, they cannot both exist within human nature. • There can only be one realm of human nature and that is the material world. • All human activities, including the mental, can be explained on the paradigm of a machine. Materialism • Hobbes was reductionist in that he believed that one kind of purported reality (the mind) could be understood entirely in terms of another (matter). • New scientific techniques of observation and measurement being used by Galileo, Kepler, and Copernicus were making giant strides in understanding the universe. • The spirit of his century suggested to Hobbes that all reality would be explained in time in terms only of the observable and the measurable. • Hobbes himself was unable to explain any mental processes in terms of the physical. • Perhaps motivating Hobbes’ view was basically his passionate faith in the advancement of science at the time. The Prima Facie (or Self-evident) Case for Materialism • The argument from common sense: • If there are other realities besides the material, can they causally interact with the material world? • If so, how can this interaction happen? If they can not interact, what does it mean to say that such a reality exists? • Please note this may be more difficult that even the mind/body problem where we do seem to have direct evidence to believe that our own consciousness exists. The Prima Facie (or Self-evident) Case for Materialism • The argument from science: • Science seems to be our most developed and useful organized body of knowledge about the world by focusing on observation and measurement of the physical material world. In the history of science, discussion of any kinds of entities other than material entities largely have been blind alleys. • The history of science is full of examples where entities once thought to be necessary to explain life and man have been replaced by fully causal explanations in terms of chemicals and biological processes. Doesn’t it seem reasonable that this also may be the case with mental states? (4:58) Modern Idealism • The founder of modern Idealism is Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1753). • Berkeley argued against Hobbes’ Materialism that the conscious mind and its ideas and perceptions are the basic reality. • Berkeley believed that the world we perceive does exist. However that world is not external to and independent of the mind. • The external world is derived from the mind. • However, there is a further reality beyond our own minds. Since we have ordered perceptions of the world which are not controlled by an individual’s mind, they must be produced by God’s divine mind.