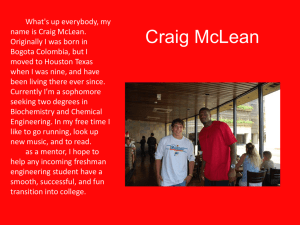

PPT

advertisement

Rectification and Alterations Law Extension Committee Diploma in Law Course Succession Law Seminar on 2 December 2015 Craig Birtles Senior Associate, Teece Hodgson & Ward Accredited Specialist, Wills & Estates Law S 29A Wills Probate and Administration Act 1898 • 29A Power of the Court to rectify wills • (1) If the Court is satisfied that a will is so expressed that it fails to carry out the testator’s intentions, it may order that the will be rectified so as to carry out the testator’s intention. • (2) Proceedings to be commenced within 18 months after DOD • (3) Leave for out of time application if the Court is satisfied that sufficient cause is shown for the failure to make the application within that period. • Applies to Grant made after 1 November 1989 and DOD prior to 1 March 2008 Craig Birtles 2015 S 27 Succession Act 2006 • (1) The Court may make an order to rectify a will to carry out the intentions of the testator, if the Court is satisfied the will does not carry out the testator’s intentions because: • (a) a clerical error was made, or • (b) the will does not give effect to the testator’s instructions. • (2) Time limit is 12 months after DOD • (3) Leave to grant extension of time if: • (a) the Court considers it necessary, and • (b) the final distribution of the estate has not been made. • Applies to DOD after 1 March 2008 Craig Birtles 2015 Protection of Executor- s28 Succession Act 2006 • 28 [cf s29A(4) WPAA] • (2) A personal representative is not liable if: • (a) the distribution was made under section 92A of PAA 1898; or • (b) the distribution was made at least 6 months after DOD and executor or administrator not aware of rectification application, • and the personal representative has complied with the requirements of section 92 PAA 1898. Craig Birtles 2015 S 92 Probate and Administration Act 1898 • (1) if: • (a) more than 6 months since DOD • (b) notice in the prescribed form has been given • (c)(d) the notice allows for not less than 30 days from publication for claims to be sent to executor and the time stated in the notice has expired; then • (2) executor or administrator is not liable for claims of which he or she does not have notice at the time of distribution [Prior to 1 March 2009 the 6 month requirement did not apply] Craig Birtles 2015 Mortenson v State of New South Wales (NSWCA, unrep, 12.12.1991) (para. 3.130) • Estate of Nina Spinks DOD 2 October 1989; Will 7 September 1987 • Husband predeceased; Illigitimate and did not know who father was; All relatives on mother’s side dead. • Under Will residue divided equally between Children of neighbours, Mr & Mrs Longworth (Peter Longworth (DOD, suicide 6/9/89), Victoria Young; Elizabeth Eassie • Partial intestacy arising from Peter’s death; Evidence that testator would not have wanted part of the estate to go to government bona vacantia • Does the will as expressed fail to carry out the testator’s intentions? • Can the testator’s intention be discerned to the point that an order can be made carrying it out? • Should the Court exercise its discretion to make an order? Craig Birtles 2015 Requirements for an order under s 27 SA • In Lockrey v Ferris [2011] NSWSC 179, it was accepted that the Court must determine the following in order to make an order under s 27: • What were the testator's actual intentions with regard to dispositions in respect of which rectification is sought? • Is the will expressed so that it fails to carry out those intentions? • Is the will expressed as it is in consequence of either a clerical error, or a failure on the part of someone to whom the testator gave instructions in connection with the will, to comply with those instructions? Craig Birtles 2015 Mirror Wills incorrectly executed (1) • Estate of Gillespie (NSWSC, unrep, 25.10.91) (para. 3.135) • DOD 11/08/1991 • Only asset in deceased’s estate was matrimonial home valued at $50,000; bank accounts passed by survivorship • Whole estate would pass to applicant in any event • Should Will be rectified to conform in all respects with the form of Will which was intended to be signed by her? • Would such an application be successful under s 27 Succession Act 2006? Craig Birtles 2015 Mirror Wills incorrectly executed (2) • • • • • Estate of Daly [2012] NSWSC 555 per White J Husband and wife; each executed the other’s mirror Will Henri Georges Daly DOD 27/8/07; Eliane Lucie Daly DOD 22/5/10; Wills 5/5/03 His Honour said that the correct course is to follow s 8 not s 27. "25. Section 27 would not confer power to make the orders sought in the amended summons. Before there can be an order for rectification there must first be a will. If no order were made under s 8, the document expressed to be the last will of the deceased [wife], but not signed by her, could not be rectified by omitting the signature of Henri Georges Daly [her husband] and deeming the document to have been signed by the deceased because the document in question would never have been the valid will of the deceased (Succession Act, s 6). If an order is made under s 8, no rectification is necessary.” • Admit to Probate in Eliane’s estate the document commencing “THIS IS THE LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT of me, ELIANE LUCIE DALY” and bearing the date 5 May 2003 Craig Birtles 2015 Mirror Wills incorrectly executed (3) • Re Estate Johnson decd [2014] NSWSC 512. • Wills 23 July 2003; Mark Johnson DOD 2/9/12; Wife made mirror Will; each signed the Will of the other • [9] “As a matter of form, an order for rectification under s 27 takes the document actually signed by a deceased person and rectifies it by incorporation of the deceased's intended text in lieu of the text of the document signed. • [10] As a matter of form, a decision made under s 8 adopts the text intended to be signed, but erroneously not signed, as the operative instrument and ignores the signature of the person who in fact signed it.” Craig Birtles 2015 Mirror Wills incorrectly executed (4) • in Re Estate Johnson decd [2014] NSWSC 512, per Lindsay J (cont) • [16] “In light of ss 8 and 27 it is not necessary, in the present case, to discount to nothing the objective, primary fact that the deceased did sign a document intending it (albeit mistakenly) to operate as his will. In my opinion, what the deceased signed was "will" enough to constitute a "will" within the meaning of s 27. That proposition is no less true because the document mistakenly signed by the defendant, instead of him, was the "will" that he, in fact, intended to operate and it can be given effect by virtue of s 8. • [17] Whether s 8 or s 27 is deployed in the service of the deceased's testamentary intentions is, in these proceedings, a matter for discretionary judgement, not a matter of jurisdiction.” Craig Birtles 2015 Examples of successful applications under s 27 • In Re Will of McCowen [2013] NSWSC 1000, per Young AJ • Estate Kevin McCowen; DOD 30/3/13 • Solicitor took instructions that testator wished to benefit third wife; residue to go to three elder children with three younger children to receive $1,000 each. • Paralegal assistant misread solicitor’s notes and the Will provided for the residue to be divided between the six children • Clerical error • Will rectified Craig Birtles 2015 Examples of successful applications under s 27 (cont) • In Coates v Wattson; Estate of Sullivan [2013] NSWSC 604 per Windeyer AJ • Estate Doreen Dorothy Sullivan DOD 1/12/11 • Clause 3(h) “the then balance of my estate to Brian Jack Coates and Janette Coates absolutely” • Clause 5 “My executor holds my estate on trust: (a)(i) Subject to para (ii) to divide it equally between those of my children who survive me.” • Evidence was solicitor’s file notes which recorded residue was to go to Mr and Mrs Coates; he did not have any instructions that residue was to go to children. He had no sensible explanation for how clauses 4 and 5 appeared in the Will Craig Birtles 2015 Examples of successful applications under s 27 (cont) • Coates v Wattson (cont) • Court found both clerical error and that Will did not give effect to testator’s instructions • In relation to knowledge and approval, his Honour said [18] “The evidence is that the will was given to the deceased and she read it and it was then executed in accordance with the law. I have said many times in lectures and other occasions that it is quite inappropriate for a solicitor to attend a lady in a nursing home, to give her a will, tell her to read it, and then ask if that's what she wanted, when normally she will say, "Yes dear." All that is evidence of is that she said, "Yes dear." It is no evidence whatsoever that the deceased knew what was in the will. The will should be read aloud and explained.” • Relevance – if this process had been followed, the mistake may have been discovered prior to execution of the Will Craig Birtles 2015 Examples of successful applications under s 27 (cont) • In NSWTAG v Ritchie [2011] NSWSC 715, Rein J rectified a Will in which a gift was made to an incorrectly named charity. The relevant will clause described the beneficiary as "World Vision Enterprises of Australia of 5 Northcliffe Road, Milsons Point", however the evidence showed that no such charity existed and, further, that no entity coming close to that description occupied the premises at 5 Northcliffe Road, Milsons Point. • Dawson v Brazier & Ors [2012] NSWSC 117, Black J rectified a Will the structure of which did not work. By clause 3(d) a legacy of $250,000 was given to one of the deceased's sons. By clause 3(i) the deceased's funds at banks and other financial institutions were given to the deceased's daughters. His Honour rectified the Will by adding the words "to be paid out of the monies held by me in banks and other financial institutions" to the legacy clause. Craig Birtles 2015 Construction of Wills • Resources: • Hon R W White, Use of Extrinsic Evidence to Construe Wills presented by his Honour for the Law Society of South Australia on 15 November 2011 (and which can be downloaded from the website of the Supreme Court of NSW); • Ten principles of construction were described by Isaacs J in Fell v Fell [1922] HCA 55 (1922) 31 CLR 368 at 273-275, and cited with approval by Hallen AsJ (as his Honour then was) in Lockrey v Ferris [2011] NSWSC 179 at [43] and in later judgments including NSW Trustee & Guardian v The Attorney General in and for the State of New South Wales [2012] NSWSC 1282 at [26]. • "Testamentary dispositions", seminar 3 in "Estate administration: Probate, Protective and Family Provision Jurisdiction" Michael Willmott SC and C Birtles for the NSW Bar Association and Law Society of NSW on 16 June 2015 Craig Birtles 2015 Construction of Wills • Ordinary meaning – ascertain the intent of the testator from the words used in the Will • Cannot change the words in a Will • Construe the Will as a whole • Relevance of precedent • S 32 Succession Act 2006 (Wills made after 1 March 2008) Craig Birtles 2015 Construction of Wills The fundamental rule stated by Viscount Simon LC in Perrin v Morgan [1943] AC 399 at 406 (cited with approval by Bryson J in Hatzantonis v Lawrence; Cox v Lawrence [2003] NSWSC 914 at [6]: • “… the fundamental rule in construing the language of a will is to put on the words used the meaning which, having regard to the terms of the will, the testator intended. The question is not, of course, what the testator meant to do when he made his will, but what the written words he uses mean in the particular case – which are “expressed intentions” of the testator.” Craig Birtles 2015 Armchair principle • Place person construing the Will in the same position as the testator – consider what surrounding circumstances were known to the testator • Examples: family tree, nickname, state of testator’s property, status of family members, evidence of other persons by the same name • Evidence of actual intention expressed outside Will not usually admissible unless equivocation in Will • Allgood v Blake (1872-73) LR 8 Exch 160 at 162). As it was put in Allgood v Blake (at 162): • "The general rule is that, in construing a will, the Court is entitled to put itself in the position of the testator, and to consider all material facts and circumstances known to the testator with reference to which he is to be taken to have used the words in the will, and then to declare what is the intention evidenced by the words used with reference to those facts and circumstances which were (or ought to have been) in the mind of the testator when he used those words. ... the meaning of words varies according to the circumstances of and concerning which they are used." Craig Birtles 2015 Armchair principle In considering the evidence which might be relevant to construction, White J distinguishes between the admissibility of evidence and what the evidence would tend to show (White J ibid at para 29). • Evidence of "the testator's knowledge of their family tree, the testator's knowledge of the status of family members or beneficiaries and the testator's habit of referring to a person by a nickname" may be admitted as "armchair" evidence - Public Trustee v Herbert [2009] NSWSC 366 at [30] Craig Birtles 2015 S 32 Succession Act 2006 • (1) In proceedings to construe a will, evidence (including evidence of the testator’s intention) is admissible to assist in the interpretation of the language used in the will if the language makes the will or any part of the will: • (a) meaningless; or • (b) ambiguous on the face of the will; or • (c) ambiguous in the light of the surrounding circumstances The common law applies in addition to the statute. Craig Birtles 2015 Construction • The common law applies in addition to the statute. • Note the other provisions in Chapter 2, Part 2.3 Succession Act 2006 (ss 29 to 46). Craig Birtles 2015 Examples: Parry v Haisma [2012] NSWSC 290 • Estate of Hinka Haisma DOD 19/9/09; Will 1/10/03 • Appointed de facto partner Richard Brewer and solicitor Stephen Parry as executors • Will contained following provisions: • 3. I GIVE the whole of my estate to RICHARD JAMES BREWER contingent upon him surviving me by 90 days, and if he does not survive me by 90 days, then and only then, clause 4 will apply. • 4. I GIVE the whole of my estate to such of my nephews and nieces as survive me by 90 days, and if more than one in equal shares. Craig Birtles 2015 Parry v Haisma (cont) • Richard Brewer survived the deceased but not by more than 90 days • The evidence was that the deceased had a particularly close relationship with the children of Richard’s brother; but that she hardly saw her own nieces and nephews. • Evidence of the blood relations that the deceased told them that she wanted to benefit them was not admitted. (Intention evidence rejected). • Evidence of third party witnesses that the deceased referred to the children of Richard’s brother as “niece” and “nephew”. • Common law – “niece” and “nephew” are relations by blood only and not by affinity. Craig Birtles 2015 Parry v Haisma (cont) White J at [54] – [57] • Dictionaries cannot be used as a substitute for judicial determination of the meaning of the words used by the deceased… but they can provide valuable assistance in ascertaining current usage. The Macquarie Dictionary … gave as the primary meaning of nephew and niece; a son or daughter of one's brother or sister. It gave as the secondary meaning; a son or daughter of one's husband's or wife's brother or sister. A son or daughter of one's de facto partner's brother or sister was not included. For some purposes laws have been passed which give de facto partners the same or similar rights as husbands or wives. Nonetheless, there are fundamental and substantial differences between relations between spouses and relations between de facto partners; most notably the absence of a formal commitment. • Extrinsic evidence will not generally be allowed to alter the natural meaning and construction of words which have a definite and clear meaning. .. I do not consider that the evidence that the deceased from time to time (and mostly after she made her will) referred to Sam and Tess Brewer as her nephew and niece, means that she intended that they be included in that description in her will Craig Birtles 2015 Power to dispense with formalities • S 8 Succession Act 2006 applies where DOD after 1 March 2008 (cf 18A WPAA 1898) • Documents not executed in accordance with S 6 SA • Purport to state testamentary intentions • (2) The document, or part of the document, forms: • the deceased person’s will; or • an alteration to the deceased person’s Will; or • a full or partial revocation of the deceased person’s Will if the testator intended it to have that effect. Craig Birtles 2015 Requirements for ITD order (Powell J form) • The requirements (albeit under s18A WPAA 1898) were accepted to be those set out by Powell J in Hatsatouris v Hatsatouris [2001] NSWCA 408, as follows: • Was there a document; • Did that document purport to embody the testamentary intentions of the person; • Did the evidence satisfy the Court that, either, at the time of the subject document being brought into being, or, at some later time, the relevant deceased, by some act or words, demonstrated that it was her, or his, then intention that the subject document should, without more on her or his part, operate as her or his will? Craig Birtles 2015 Is the “without more” test still relevant? • In Re Estate of Masters (decd); Hill v Plummer (1994) 33 NSWLR 446, Mahoney JA, at 462 said that the dispensing provisions should be given a “beneficial application”. • In NSW Trustee and Guardian v Halsey; Estate of Von Skala [2012] NSWSC 872, White J at [15] restated the requirement as “whether the deceased intended the document to be his or her testamentary act, that is, to have present operation as a will” • In Estate of Laura Angius; Angius v Angius [2013] NSWSC 1895 Hallen J at [276] said at [260] “In my view, the use of the words "without more on her, or his, part", does not really add anything.” Craig Birtles 2015 Is the “without more“ test still relevant? (2) • Opportunity arose for the NSW Court of Appeal to consider this in • Burge v Burge [2015] NSWCA 289 (24 September 2015) • [51] Ground three focussed upon the formulation of the third element of the test arising under s 8 (and its predecessor, s 18A of the Wills, Probate and Administration Act 1898 (NSW)) in Hatsatouris v Hatsatouris at [56]: • “Did the evidence satisfy the Court that, either, at the time of the subject document being brought into being, or, at some later time, the relevant Deceased by some act or words, demonstrated that it was her, or his, then intention that the subject document should, without more on her, or his, part operate as her, or his, Will?” (Original emphasis). • [52] The short answer to this ground is that nothing in the reasoning of the primary judge suggests that any material weight was given to the emphasised words. Craig Birtles 2015 Wills bearing a mark or signature but not witnessed properly • Newman v Brinkgreve; Estate of Verzijden [2013] NSWSC 371, per Hallen J at [104] – his Honour accepted that a signature placed at the foot of a testamentary document, would, in most cases, carry the implication that the testator intended the signature to give testamentary effect to the document. • Estate of Radziesweski, deceased; Lalic v State of South Australia (1982) 29 SASR 256, in which the severely physically incapacitated testator made marks on the Will in the presence of two witnesses but did not sign the Will; • Estate of Williams, Deceased (1984) 36 SASR 423 in which a husband executed his wife’s will in the presence of his neighbours and the wife executed her husband’s will; • Estate of Puruto [2012] NSWSC 827 in which White J admitted a signed document headed “instructions” to probate. Craig Birtles 2015 Instructions for a Will • In Angius, Hallen J sets out the principles applicable to the question of whether instructions may be the subject of a grant of probate pursuant to the dispensing provisions (quoting his Honour’s own judgment in Newman v Brinkgreve; Estate of Verzijden [2013] NSWSC 371). His Honour accepts that, upon consideration of the facts of the particular case, instructions for a will may be the subject of a grant of Probate if it is established that the deceased intended the document to operate in the absence of a more formal document. • Contrast Certoma’s view Craig Birtles 2015 Alterations • Before execution of Will – no additional requirement but proof requirement – Part 78 r 29 Supreme Court Rules 1970 requires evidence that alteration made before execution of the Will if it is not duly authenticated or otherwise validated. • After execution of Will – if executed in the manner which a will is required to be executed (s 14(1) SA 2006) • S 14(3) SA 2006 – if a Will is altered it is sufficient compliance with the requirements for execution if the signatures of the testator and of the witnesses to the alteration are made: • (a) in the margin, or on some other part of the will beside, near or otherwise relating to the alteration; • (b) as authentication of a memorandum referring to the alteration and written on the Will. Craig Birtles 2015 Obliteration • S14(2) Succession Act 2006 (restates s 18(1) WPAA 1898) • Subsection (1) does not apply to an alteration… if the words or effect of the will are no longer apparent because of the alteration. • “apparent” means apparent on the face of the will and does not mean capable of being made apparent by extrinsic evidence Craig Birtles 2015 Dependant relative revocation • Where the substitution of new words is ineffective (perhaps because the alteration is not property attested). • If it can be shown that the testator intended that the obliteration would only take effect if the new words were effective; then the obliterated words, if it is possible to ascertain what they are; will be given effect. • Eg; deleting the amount of a legacy and replacing it with a different amount. Craig Birtles 2015 Presumptions • Query relevance in light of s 8 SA • Unattested alterations made after Will presumed to have been made after Will and of no effect (onus of proof) • Pencil alterations before Will presumed to be deliberative and not form part of the Will • Will incomplete without alterations, presume to be made before execution • Codicil referring to alterations incorporates them • Codicil not referring to alterations presumed to have been made after codicil Craig Birtles 2015 Revocation • S 11(e)(f) Succession Act 2006 • Will may be revoked by testator, or some person in his or her presence or at his or her direction burning tearing or destroying the Will with the intention of revoking it; or • By the testator, or by some person in his or her presence or at his or her direction, writing on the will or dealing with the will in such a manner that the Court is satisfied from the state of the Will that the testator intended to revoke it Craig Birtles 2015 Revival of a revoked document by ITD (1) • White J in Slack v Rogan & Anor; Palffy v Rogan & Anor [2013] NSWSC 522 (particularly at [29] to [48]) is authority for the proposition that an informal testamentary document is capable of reviving a revoked document. • Estate of Aidan Patricia Rodan DOD 16/3/11 • Husband John DOD 23/6/94 • Son Michael DOD 23/3/03 • Will in favour of nephew • 23/12/07 Will revoked prior Will and gave residue to Michael’s children; Probate granted on 18 May 2011 Craig Birtles 2015 Revival of a revoked document by ITD (2) • Claim for revocation of grant of Probate and declaration under s 8 regarding a later document dated 4/12/08. • Deceased’s signature witnessed by one person, not two • See s 15 SA 2006 • Alternative Family Provision claim • File note signed to confirm instructions • Short term memory loss Craig Birtles 2015 Revival of revoked document by ITD (3) • Solicitor’s file note • "I attended upon Aidan Rogan at about 4PM on 4 DECEMBER 2008. I showed to her her wills made on 16.7.1986, 19.11.1999, 19.12.2001, 29.12.2003. She considered these wills for over 30 minutes. I explained to her that the main beneficiary of her last will was her nephew James. I asked her whether she wanted to make provision for others including her grandchildren. She said to me 'No leave it as it is'. I said 'Then you did not want to change your 2003 will in which apart from gifts of very minor items to Marjorie & Yvonne you leave the rest of the estate ot your nephew James. She replied 'Yes that's correct.' • TO PHILIP ABIGAIL • I acknowledge that I do not want to change my will & I understand that my home & cash & bank monies will pass to my nephew Jim Slack. • A Rogan • 4. 12.2008" Craig Birtles 2015 Revival of revoked document by ITD (4) • [51] “[in order to succeed under s 8] She must have intended that the document she signed to have testamentary effect. That is, she must have intended the document to have a legally operative effect on the disposition of her property on her death.” • [52] “It is clear that she expected that her property would pass to Mr Slack not by reason of the document she signed on 4 December 2008, but pursuant to the will of 29 December 2003. But that does not determine the question whether she nonetheless intended that the document should have testamentary effect if that were needed to give effect to her wishes. That question was not asked of her. There is no direct evidence that she had that specifically in contemplation. “ Craig Birtles 2015 Revival of revoked document by ITD (5) • Intention inferred • [55] “The better view is that Mrs Rogan intended the document to record what she intended to happen to her estate after her death and intended the document to bring that about if it were necessary. Such an intention is sufficient to satisfy the requirement of s 8 that the deceased person intend the document to form his or her will. It is a conditional intention which is operative because the condition was satisfied.” Craig Birtles 2015 Goods of Sykes (1873) 3 P and D 26 (para. 6.20) • Presumption alterations made after Will but rebutted by evidence of declarations made prior • DOD 16/6/1872; Will 9/11/1869; Codicil 10/8/1870 • Name of Executor “Dr John Scott” written as alteration • Evidence was that testator told custodian of Will that Dr John Scott was his executor • Execution of Codicil was confirmation of the Will in the altered state Craig Birtles 2015 Williams v Ashton (1860) 70 ER 685 (para. 6.25) • Unattested alteration • Onus on party propounding the alteration to show that the alteration was made prior to executing Will • Evidence was that she said that she had made alterations but no evidence of what alterations she had made. • Vice Chancellor Sir Pagewood: “If a general statement by a testatrix that she had made some alterations in her Will were to give validity to any alterations found in the instrument after her death, that would enable her, at any time after such statement, to make as many unattested alterations as she pleased.” Craig Birtles 2015 Goods of Hall (1871) LR 2 P and D 256 (para. 6.30) • Court must determine whether words are final or deliberative • Estate of Peter Brames Hall; Will 3/6/1864; Codicil 9/3/1871 • Will marked with pencil alterations; some initialled by testator, others marked “query” • Alterations not effective Craig Birtles 2015 Goods of Itter [1950] P 130 (para. 6.40) • Will Nov 1942; Codicil Feb 1944 • Pasted paper over Will paragraphs with alterations • Alterations not effective • Writing beneath could only be seen by making a new document • But dependent relative revocation • Obliterated parts were amounts of legacies • Intention to revoke the legacies covered by the slips only if new bequests were effectively substituted • Initial legacies effective Craig Birtles 2015 Ffinch v Combe [1894] P 191 (para. 6.35) • Estate of Captain George Fahie Horsford • Will 1/4/1868; Codicil 29/7/1874 • 4 paragraphs; 2 of which had pieces of paper stuck over parts of them with alterations • Alterations not effective • Whether concealed words remain “apparent” • Concealed words capable of being read by placing an opaque substance, such as brown paper, against it and holding it up to the light • Words still “apparent” • Physical interference with the document not permitted Craig Birtles 2015