Dispersal and Migration

advertisement

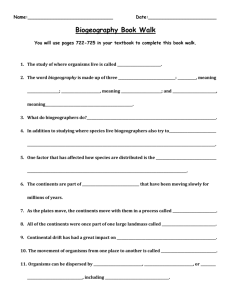

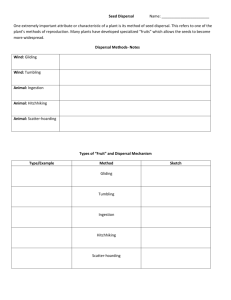

Dispersal and Immigration There are several fundamental processes in biogeography: Evolution Speciation Extinction Dispersal These are the processes by which organisms respond to changes in the geographic template. The relative importance of movement, or dispersal, has been the subject of great debate. The early “dispersalists” included Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace and Asa Gray. They argued that disjunctions (a situation in which two closely related populations are separated by a wide geographic distance) could be best explained as the result of long distance dispersal. Wallace Gray Darwin The dispersalists were opposed by the “extremists”, who believed that disjunctions had resulted from movement along ancient corridors that had disappeared. Lyell Among the leaders of the extensionist movement were Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker. Hooker No evidence was ever discovered for the lost corridors proposed by the extensionists. However, evidence surfaced in the 20th Century for a new, powerful means of dispersal: continental drift. The movement of continents could raft populations away from each other and separate them in vicariant events (tectonic, climatic, or oceanographic occurrences that isolate previously connected populations). As a result, the debate between dispersalists and extensionists has been replaced by a debate between dispersalists and vicariance biogeographers. What is dispersal? Simply, the movement of organisms away from their birthplace. Often, confined to a particular life history stage. Don’t confuse with dispersion, which refers to the position of individual organisms with respect to others in the population. Dispersal is an ecological process that plays an adaptive role in the life history of the organism involved. In other words, the fitness of the organism is increased in some way through the process of dispersal. Why? There’s always a trade-off. Dispersing individuals probably face reduced interspecific competition, but there’s always the chance of finding a less suitable environment. Look at it this way. The “parental” environment was obviously good enough to allow the parent organisms to reproduce. Leaving that environment is risky, but it must be worth the risk. The role of dispersal in biogeography is different. Biogeographers are interested in those dispersal events in which species change their range by dispersing over long distances. These events are rare, and largely random. They are, however, critical to understanding the distribution of organisms. Dispersal and Range Expansion In order to expand its range through dispersal, an organism must be able to: 1. Reach a new area. 2. Survive the potentially harsh conditions occurring during the passage. 3. Survive and reproduce in the new area to the extent that a new population is established. Biogeographers often distinguish three types of dispersal events that can accomplish this: 1. Jump dispersal (“sweepstakes”) 2. Diffusion. 3. Secular migration. How do they operate? Jump dispersal is simply the colonziation of new areas over long distance. An example can be seen in the rapid recolonization of Krakatau after all life was wiped out by the volcanic explosion of 1883. Read the account in your text. We can see the same thing over longer distances and greater time periods for many other archipelagoes. The Galapagos lie 800 km west of Ecuador in the Pacific Ocean. The Hawaiian Islands lie 4000 km west of Mexico. In both cases, there is indisputable evidence of many groups of organisms reaching the islands by dispersal. Long-distance dispersal likely has a selective component. Certain organisms, possessing certain traits, are more likely to be successful. Bats are often common island inhabitants. Nonvolant (non-flying) mammals, amphibians, freshwater fish, and other forms are typically absent from island populations. Long-distance dispersal offers three important consequences for biogeographers: 1. It offers a way to explain wide, and often discontinuous, distribution patterns. 2. It helps to account for the similarities and differences among biotas inhabiting widely separated, but similar, habitats. 3. It emphasizes the importance of anthropogenic (human-induced) long-distance transport of species. Diffusion is the gradual spread of of individuals outward from the margins of a species’ range. It is a slower form of range expansion involving not just individuals, but populations. An example is provided by the cattle egret, Bubuculus ibis. Read your texts’ account of the spread of the cattle egret over the last century. Many other examples of range expansions include: European starlings in North America House sparrows in North America American muskrat in Europe Nine-banded armadillo in North America European rabbit in Australia Red fox in Australia European starling Sturnus vulgaris House sparrow Passer domesticus American muskrat Ondatra zibethica Nine-banded armadillo Dasypus novemcinctus European rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus Red fox Vulpes vulpes Imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta There are many examples of range expansions among insects, as well. Some of the most notable include imported fire ant… Read the abstract of this paper “Africanized honeybee” Apis mellifera …and the Africanized “killer” honey bee We have also seen range expansion through diffision in many plants. Examples include the spread of “Fertile Crescent” crops across Western Europe…. …the spread of oaks (Quercus spp. in Great Britain….. …the spread of elm (Ulmus spp.) in Great Britain,…. …and the spread of purple loosestrife (Lythrium salicaria) in North America. Secular migration occurs much more slowly. So slowly, in fact, that organisms can evolve during the process. An example can be seen in the evolutionary divergence of the camel family during its spread across the world following its origins in North America. Organisms can disperse either actively or passively. The terms vagility and pagility refer to the ability of organisms to disperse actively or passively. Some animals have the capacity to disperse great distances by flight. Golden plovers breed in the Arctic and winter in southern South America, southern Asia, Australia, and the Pacific islands. Migrating individuals regularly fly nonstop from Alaska to Hawaii, a distance of 4000 km. Monarch butterflies migrate great distances, flying from southern Canada to the southern U.S. and central Mexico. Individuals may fly as far as 375 km in four days and 4000 km during their lifetimes. Most overwintering individuals of the eastern populations gather in winter congregations in Mexico. The northern limits correspond with the northern extent of its host plant, milkweed. North American plants use a variety of diaspores to enable dispersal from the mother plant. Many insects, spiders, and mites disperse through the atmosphere, forming an aerial plankton. The cnidarians Velella and Physalia have sails or floats that allow them to drift across the surface of the ocean. In both cases, the orientation of the sail causes them to drift either to the right or left. This may enable them to remain within a restricted area. Many organisms employ other organisms for long distance transport. This process is known as phoresy. Parasites are a good example. Many plants have seeds that adhere to the coats of animals. Wading birds often carry seeds or eggs in the mud on their feet. Cockle burr Seeds of fruits may be carried in the digestive tracts of animals. Seeds in coyote scat Barriers The nature of long-distance dispersal means that organisms often have to survive for periods of time in environments that are hostile to them. These environments constitute physical and biological barriers to dispersal. The effectiveness of such barriers in preventing dispersal depends not only on the nature of the barrier, but also on the organism dispersing. Barriers are species-specific phenomena. Most freshwater zooplankton have resistant stages that help facilitate long-distance dispersal. As a result, the same species are found in widely separated locations in North America, Europe, and Asia. Ostracod Fish, on the other hand, lack such dispersal mechanisms. As a result, similar fish species are only found in bodies of water that have, at some point, been connected. Walleye The sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) is found in estuaries and mangrove swamps throughout the Caribbean. It has been able to colonize these habitats by dispersing many hundreds of miles across ocean water. It’s ability to tolerate wide ranges of salinity makes this possible. The many species of sunfish (Lepomis spp.) of the southeastern United States, lacking this tolerance, were unable to disperse to Caribbean islands. The vegetation zones of the American Southwest have changed dramatically since the last glacial maximum (~18,000 years ago). Today, the cool, moist, mountainous regions are isolated by large distances of inhospitable desert. Small terrestrial mammals, reptiles, and amphibians probably colonized the isolated mountains of the region during the Pleistocene when they were largely connected. Dan Janzen made the point that mountain passes in the tropics are “effectively higher” than those in temperate regions since temperate organisms must deal with a greater temperature range over the course of the year. Physiological barriers are created by environmental conditions which organisms (or their propagules) are unable to survive long enough for dispersal. Such barriers can be presented by salt (or fresh) water or unfavorable temperatures, The bird family Alcidae (auks, puffins, and murres) is restricted to cool areas of the Northern Hemisphere even though they are strong flyers. The tropics apparently represent a strong physiological barrier. The nature of barriers may change with the season. In temperaate regions of North America, large bodies of water serve as barriers to the movement of many terrestrial species. However, during winter these waters may freeze and allow movement across them. Many species of terrestrial mammals move across the ice of the St. Lawrence River in New York state. Biotic Exchange and Dispersal Routes Biogeographers often distinguish three kinds of dispersal routes based on how they effect biotic interchange. They are: 1. Corridors. 2. Filters. 3. Sweepstakes routes. Corridors are dispersal routes that allow movement of most taxa from one region to another. They do not selectively discriminate against one form, but rather allow a balanced assemblage of plants and animals to cross them. The areas at the two ends of a corridor should contain a fairly similar assemblage of organisms. The Bering Land Bridge which existed some 20,000 years ago likely functioned as a corridor which allowed organisms to pass from northern Eurasia to North America with very little selection of the types that could pass. Conditions along the corridor would have differed little from those on either end. A filter is a dispersal route that exercises some selection over the types of organisms that can pass through it. As a result, the colonists are a somewhat biased subsets of those that could potentially pass. The Arabian subcontinent acts as a filter in that only certain mammals, reptiles and ground birds can disperse between northern Africa and central Asia. The Lesser Sunda Islands form a two-way filter for the reptilian fauna of southeastern Asia and Australia. This region is sometimes known as “Wallacea”, and is bisected by Wallace’s Line. The deserts of the American southwest may act as a two-way filter between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Madre to the south. The desert separating the two mountain ranges have allowed limited mixing of the two biotas. This mixing was greatest during the glacial maximum, when the forest regions were most greatly expanded and desert climates reduced. Sweepstakes Routes Sweepstakes dispersal refers to the crossing of barriers by rare, chance events. Such events, while highly unlikely in the short term, are likely, even probable, over the long term. Your text tells of 15 green iguanas that were rafted 200 miles across the Caribbean as the result of Hurricanes Luis and Marilyn in 1995. In essence, they got lucky. They won the “sweepstakes”. Another example of a sweepstakes route is revealed in the limits of the distributions of eight different families of land snails in the South Pacific. Each of the groups has its origin in Southeast Asia and then spread, by sweepstakes, southward and eastward.