HCV HBV - Online Abstract Submission and Invitation System

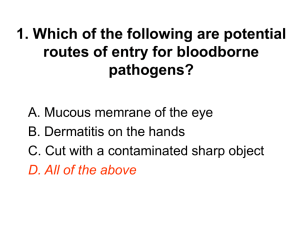

advertisement

Back to Basics: Ensuring Safe Injection Practices Joseph Perz, DrPH Prevention Team Leader Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Gina Pugliese, RN MS Vice President Safety Institute, Premier healthcare alliance No disclosures or conflicts of interest The findings and conclusions in this presentation are those of the presenters and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 3 Outbreaks of HBV-HCV still happening in 2010 4 Injection Safety • Measures taken to perform injections in a safe manner for patients and providers • Part of Standard Precautions – Infection prevention practices that apply to all patients, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status, in any healthcare setting • Healthcare should not provide any opportunity for transmission of bloodborne viruses – Patient protections in the context of IV injections should be on par with transfusion safety and healthcare worker safety (OSHA BBP Standard) 5 HBV- HCV Infections Background Features of HBV, HCV and HIV relevant to healthcare transmission Characteristic HBV HCV # with chronic infection (U.S.) 1.25 million 3.8 million Titer (per ml)* 108-9 106 >week days 30% ~3% * Blood, acute infection Environmental stability Infectivity (needlestick) Beltrami et al, Clin Microbio Reviews, 2000. MMWR 2001;50(No. RR-11). Bond et al. Lancet 1981; 8219:550-1. Shikata et al.. J Infect Dis 1977;136:571–76. 7 7 Reported acute cases per 100,000 Era of decreasing acute HBV/HCV incidence 7 6 •HIV prevention •Hepatitis B vaccine •Screening of blood donors •Healthcare worker safety Decline in healthcare transmission 5 4 HBV Est. new cases 3 2 HCV 43,000 1 0 1992 17,000 1997 2002 CDC. Surveillance for Acute Viral Hepatitis – United States, 2007. MMWR 2009;58 (No. SS-3). 2007 8 However, increase in viral hepatitis outbreaks associated with healthcare procedures • Considered uncommon, isolated events in US – Not identified via acute HBV/HCV surveillance data • Increase in the number, size of outbreak investigations, number of persons affected • Increase in attention – Public, media, public health officials, healthcare providers/professional organizations 9 TRANSMISSION OF BLOODBORNE PATHOGENS VIA UNSAFE INJECTION PRACTICES SOURCE Infectious person, e.g. chronic, acute CONTAMINATED INJECTABLE EQUIPMENT OR PARENTERAL MEDICATION CASE Susceptible, non-immune person 10 Person-to-person transmission of blood borne viruses during blood glucose monitoring Newly infected persons now become source of infection for others, the cycle continues 2. Contaminated equipment/supplies 1. Infected Indirect contact transmission1 3. Susceptible 11 1. HICPAC: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings, 2007 www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html 11 The Infection Control Ideal: “Each Patient an Island…” SOURCE Infectious person, e.g. chronic, acute CASE Susceptible, non-immune person 12 Standard Precautions • Assume that anyone might be infected with a bloodborne pathogen • Basic infection control principles that apply every where and every time healthcare is delivered • Safe Injection Practices – Never administer medications from the same syringe to more than one patient – Do not enter a vial with a used syringe or needle – Minimize the use of shared medications – Maintain aseptic technique at all times 13 Outbreaks due to Unsafe Injection Practices – Summary of US Experience over the Past Decade • Steady increase in requests for assistance in investigating infections and outbreaks potentially stemming from unsafe injection practices • Over 51 outbreaks of hepatitis B or C have occurred in healthcare settings – Approximately one-fourth investigated in the last 24 mos – Majority attributable to unsafe injection practices or related breakdowns in safe care • Approximately 20 outbreaks involving bacterial pathogens (e.g., drug resistant gram negative and invasive staph infections), typically resulting in bloodstream infections – Prolonged hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics 14 Healthcare-associated HBV/HCV outbreaks by year reported – US July 1998 to June 2009 10 9 8 7 No. of outbreaks 6 •51 outbreaks (42 non-hospital) -17 long-term care -16 outpatient med/surg clinics -9 hemodialysis -9 hospital •>75,000 persons potentially exposed •620 persons newly infected 5 4 3 2 1 0 09 20 08 20 07 20 06 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 20 99 19 98 19 15 Features of transmission of HBV-HCV Outbreaks July 1998 to June 2009 • In non hospital settings (42 of 51, 82%) • Patient-to-patient transmission due to poor infection control practices by staff (47/51, 92%) – During administration of injections – Cross contamination during hemodialysis, blood glucose monitoring • Preventable with standard precautions and aseptic technique 16 Indirect transmission of HBV during blood glucose monitoring Stable in environment for at least 7 days1 Transmission via contaminated surfaces/equipment High viral titer: virus present in absence of visible blood2 1: Bond et al. Lancet 1981; 8219:550-1. 2: Shikata et al. J Infect Dis 1977;136:571–76. 19 19 What happens when Safe Injection Practices (SIP) are not followed? • Improper use of syringes, needles, and medication vials has resulted in: – Infection of patients with bloodborne viruses, including hepatitis C virus, and other infections – Notification of thousands of patients of possible exposure to bloodborne pathogens and recommendation for HCV, HBV, and HIV testing – Referral of providers to licensing boards for disciplinary action – Legal actions such as malpractice suits filed by patients 20 What factors are contributing to an increase in outbreaks in the ambulatory care setting (ACS)? Trends in Ambulatory Care Visits, United States, 1996-2006 1 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr008.pdf 22 Growth in Outpatient Care • Shift in healthcare delivery from acute care settings to ambulatory care, long term care and free standing specialty care sites • Dialysis Centers – 2008: 4,950 (72% increase since 1996) • Ambulatory Surgical Centers – 2009: 5175 (240% increase since 1996) • Approximately 1.2 billion outpatient visits / year – Quick turnover of patients – Lack of systematic surveillance to detect infections – Regulatory requirements varied widely settings and little oversight 23 Viral Hepatitis Outbreaks (n=15) in Outpatient Settings due to Unsafe Injection Practices, 2001-2009 MM State Setting Year Type NY Private MD office 2001 HCV NY Private MD office 2001 HBV NE Oncology clinic 2002 HCV OK Pain remediation clinic 2002 HBV+HCV NY Endoscopy clinic 2002 HCV CA Pain remediation clinic 2003 HCV MD Nuclear imaging 2004 HCV FL Chelation therapy 2005 HBV CA Alternative medicine clinic 2005 HCV NY Endoscopy/surgery clinics 2006 HBV+HCV NY Anesthesiologist/pain clinic 2007 HCV NV Endoscopy clinic 2008 HCV NC Cardiology clinic 2008 HCV NJ Oncology clinic 2009 HBV FL Alternative medicine clinic 2009 HCV 24 Examples of Bacterial Outbreaks due to Unsafe Injection Practices, 2008-2009 • FL – pain clinic – 7 cases – Mycobacterium abscessus – Epidural injections; all patients required lamenectomy • FL – pain clinic – 24 cases – invasive S. aureus – Epidural + other lumbar injections; 10 required lamenectomy • NYC – pain clinic – 9 cases – Klebsiella pneumoniae – Sacroiliac joint injections; 4 patients hospitalized • WV – pain clinic – 8 cases – invasive S. aureus – Epidural injections; 7 patients hospitalized (range 5-23 days) Common elements: reuse of single dose contrast dye and other unsafe injection practices / infection control deficiencies • GA – primary care clinic – 5 cases – S. aureus (MSSA) – Joint injections; all patients hospitalized ≥1 week 25 Patient Notifications for Bloodborne Pathogen Testing Due to Unsafe Injection Practices, Outpatient Settings, 2007–2009 • New York City – Endoscopy clinic – Hepatitis C virus transmission 4,500 patients notified • Long Island, NY – Pain Management Clinic – Hepatitis C virus transmission 10,400 patients notified • Michigan – Dermatologist – Fraud investigation 13,000 patients notified • Las Vegas, NV – Endoscopy clinic – Hepatitis C virus transmission >50,000 patients notified • North Carolina – Cardiology clinic – Hepatitis C virus transmission 1,200 patients notified • New Jersey – Oncology clinic – Hepatitis B virus transmission 6,000 patients notified 26 27 What are some of the incorrect practices that have resulted in transmission of pathogens? • Direct (i.e., “overt”) syringe reuse – Using the same syringe from patient to patient • Indirect syringe reuse – Accessing shared medication vials or IV bags with a used syringe • Reuse of single dose vials • Sharing of blood contaminated glucose monitoring equipment 28 Example of outbreak attributed to Direct Syringe Reuse • 2002: Oklahoma pain clinic – Example of “multidose syringe” technique • Loaded a syringe with enough medication to treat multiple patients • Reused this “prefilled’ syringe to inject into heparin lock attached directly to an IV – 71 cases of HCV and 31 cases of HBV Comstock et al. ICHE 2004;25:576-583 29 Provider-to-Patient Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Associated with Diversion of Fentanyl, Colorado 2009 • HCV-infected surgery technician stole fentanyl syringes that had been predrawn and left unattended in ORs • Contaminated syringes were refilled with saline and swapped with unused syringes • 24 patients infected; nearly 6000 notified • Tech sentenced to 30 years 30 Narcotics Theft a.k.a. “Diversion” • Diversion has emerged as the leading cause of provider to patient HCV transmission • Prevention needs extend beyond traditional “infection control” – Limit opportunities for access or deception • Good example of need for safety- engineered solutions and system approach 31 Indirect Syringe Reuse Nevada endoscopy center HCV outbreak investigation, 2008 • Syringes were reused to withdraw multiple doses for individual patients • Remaining volume in single dose propofol vials was used for subsequent patients • The vial became the vehicle for HCV spread 32 Example of outbreak attributed to reuse of single dose vials • 1991-1993, 7 hospitals experienced outbreaks traced to mishandling of propofol • Six different bacterial pathogens • Wide variety of lapses in aseptic technique • “...the larger vials look like multidose vials, and our investigations revealed that the vials are sometimes being used for an extended period of time, for more than one patient or procedure, and to refill syringes meant to be used only once.” NEJM 1995 333:147-154 34 35 • Pain Clinic – 7 cases – Serratia marcescens – Spinal injections; all patients hospitalized • Breaches in aseptic handling of injections – Reuse of syringes to access/combine multiple medications likely resulted in extrinsic contamination of reused single-dose vials of contrast solution Clin J Pain 2008;24:374–380 36 Single dose Single dose bottle Photo: Don Weiss, NYCDOMH 37 ARCH INTERN MED/VOL 170 (NO. 8), APR 26, 2010 • Overall, 74% of drug administrations had at least 1 procedural failure; 25% had clinical errors • Interruptions occurred in 53% of administrations • Error rate and severity increased with the number of interruptions • Aseptic technique compliance was 83% 38 Examples of outbreaks attributed to sharing blood contaminated glucose monitoring equipment Practices associated with HBV transmission during assisted blood glucose monitoring: re-use of blood contaminated devices, poor infection control Sharing of fingerstick devices Blood contamination of glucose testing meters Failure to change or use gloves, perform hand hygiene between procedures Patel et al. ICHE 2009;30:209-14 Thompson et al. JAGS 2010; 58:914–918, 2010. 40 40 An emerging problem: the new generation of devices Sharing of multi-lancet fingerstick devices reported as cause of HBV infection outbreak in Nursing Home1 Multi-lancet fingerstick device Sharing of multidose insulin pens reported2,3 Multidose Insulin Pens 41 1: Gotz et al. Eurosurveillance 2008;13:1-4 2: www.newsinferno.com/archives/3066 3. www.lcsun-news.com/ci_11670031 41 What are we doing to ensure safe injection practices? 42 A comprehensive approach is needed • Surveillance and investigation capacity – Recognize and contain transmission – Inform prevention • Professional oversight, licensing, and public awareness • Healthcare provider education and training • Improvements in medical devices and medication packaging • Patient empowerment 43 Oversight and Enforcement • Increasing efforts to strengthen regulatory and accreditation standards across healthcare settings – Particular focus on infection control • Collaboration with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services – Expanded incorporation of infection control requirements into conditions for coverage and inspection procedures 44 Infection control survey tool for ambulatory surgical centers http://www.cms.hhs.gov/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCLetter 09_37.pdf 45 • Labeling and sizing that are appropriate for the clinical setting and application • Injection versus infusion / IV drip 46 Challenges • Cost containment and the drive for efficiency • Trend toward patient care settings where infection control programs are lacking • Ingrained behaviors – “unthinking force of habit” • “Culture of complacency” vs. “safety culture” 47 THEN 48 NOW 49 Unsafe injection practices are not intentional but result from lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and mistaken beliefs Misperceptions • I changed the needle so I can reuse the syringe • The vial says single does but it has enough medication for more than one patient, so I can use it 51 How have providers justified syringe reuse? • Mistaken belief that the following practices prevent contamination and infection transmission – Changing ONLY the needle between patients (not the syringe) – Injecting through intervening lengths of IV tubing – Maintaining constant pressure on the plunger to prevent backflow – Lack of visible contamination or blood 52 Examples of some “BIG IFs” • IF I’m going to be throwing away this vial after this case, I can reuse this syringe to draw more meds • IF we always use a new needle and syringe to draw meds, it’s OK to reuse vials • IF I’m very careful, I can safely predraw multiple syringes from this saline bag or vial • IF I keep things straight, I can predraw meds for the next case during this case 53 How are we doing? Premier Safety Institute National Survey of Injection Practices CDC Safe Injection Practices Survey Premier Safety Institute Electronic survey: Link to on-line survey sent in email and included in newsletters directed at clinicians in acute and nonacute healthcare settings, May-June 2010 Collaborating organizations: – APIC, AAAA, AACN, AAAHC, ASHP, INS, Innovatix, PRHI, SHEA, SGNA Number of respondents: 7,164 (as of June 3) Survey information and results at www.premierinc.com/injectionpractices CDC 55 Resources – Guidelines for Education and Training CDC 57 58 Injection Safety Recommendations • Use aseptic technique during the preparation and administration of injected medications • Do not use medication drawn into a single syringe for multiple patients, even if the needle is changed • Consider a syringe or needle contaminated after it has been used to enter or connect to a patients’ intravenous infusion bag or administration set • Do not enter a vial with a used syringe or needle Adapted from: CDC. Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_isolation.html 59 Minimizing the use of shared medications affords an extra layer of protection to reduce patient risk • Use single-dose medication vials whenever possible • Single-dose vials should not be used for more than one patient • Assign multi-dose vials to single patient whenever possible • Do not use bags or bottles of intravenous solution as a common source of supply for more than one patient Adapted from: CDC. Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_isolation.html 60 CDC Materials www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/injectionsafety.html 61 62 63 64 65 SPIRIT Audit Tool for Injection Practices U of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers Safe Injection Practices Review IT Survey (SPIRIT) Adapted from: APIC Position Paper: Safe Injection, Infusion and Medication Vial Practices www.apic.org 66 Acknowledgements • • • • • Melissa Schaefer, CDC, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion Nicola Thompson, CDC, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion Judene Bartley, Premier Safety Institute Cathie Gosnell, Premier Safety Institute Lisa Sturm, U of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers 67 Thank you Jperz@cdc.gov gina_pugliese@premierinc.com 69