Draft Liverpool's Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy

advertisement

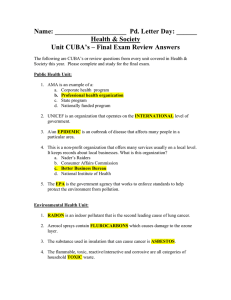

VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Liverpool’s Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy Draft 4Document for Consultation 1 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Draft VAWG Strategy Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is one of the most pressing human rights violations of our time and is a key cause and consequence of gender inequality. Both these affirmations are explicit in the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.1 The UN Declaration and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW ) make clear that such violence is gender-based, which, as well as having severe, long-term impacts on individual victims/ survivors, is instrumental in restricting the rights and fundamental freedoms of women as a social group. 2 The UN definition of VAWG is placed within a framework of structural gender discrimination: it is this definition that has been adopted by the UK Government in its ‘Call to End Women and Girls Strategy’: “Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” 3 The UN gender equality and human rights framework for preventing and addressing VAWG places international obligations on member states at national and local levels, which are reflected in UK public sector equality legislation and the national Strategy Call to End Violence Against Women and Girls.4 This strategy enables us to develop our response to VAWG in relation to all relevant gender equality requirements. This strategy will utilise the ‘Six P’s’ framework adapted and developed by the End Violence Against Women Coalition in its template for an integrated strategy on violence against women.5 These are: Perspective, Policy, Prevention, Provision, Protection and Prosecution 1 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm 2 UN Division for the Advancement of Women / Department of Social and Economic Affairs (2010) Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women. New York. Accessed at: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/vaw/handbook/Handbook%20for%20legislation%20on%20violen ce%20against%20women.pdf 3 HM Government (2010) Call to End Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy 4 Council of the European Union (2012) Council conclusions on Combating Violence Against Women, and the Provision of Support Services for Victims of Domestic Violence. Brussels: Council of European Union; UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women; HM Government (2010) op.cit. 5 Coy, M., Lovett, J., and Kelly, L. (2008) Realising Rights, Fulfilling Obligations. London: EVAW 2 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Perspective Liverpool Citysafe Partnership will ground all its work relating to VAWG in a comprehensive and coherent strategic perspective. This covers the principles and the definitions we will use to guide and co-ordinate all our work, ensuring all agencies and departments embody a shared understanding of, and commitment to, the actions that are needed to tackle all forms of VAWG. Definition VAWG is violence that is directed against a woman or a girl because she is female, or that affects women and girls disproportionately. It covers actions which harm or cause suffering or indignity to women and children: acts that inflict physical, mental or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion (e.g. force, lack of consent and exploitation), and other deprivations of liberty. The different forms of violence against women - including emotional, psychological, sexual and physical abuse, coercion and constraints, including financial coercion, threats and bullying - are interlinked, and often overlap. They have their roots in gender inequality and gendered power imbalances and are therefore understood as gender-based violence. It is men who overwhelmingly carry out such violence, and women who are overwhelmingly the victims of such violence.6 Gender-based violence includes: Physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring in the family, or caregiving domestic environment, within the general community or in institutions, including: domestic abuse, rape, sexual violence including coercion and lack of consent, incest and child sexual abuse, femicide, and rape as an act of terror or conflict. Stalking: repeated (i.e. on at least two occasions) harassment causing fear, alarm or distress, most commonly in the context of relationship ending. It can include threatening phone calls, texts or letters; damage to property; surveillance of and following the victim, relaying threats through children usually in the context of child contact situations. Sexual harassment, intimidation and sexual bullying at work, in educational establishments and in the public sphere, including through the use of public electronic communication. This includes, but is not limited to, obscene comments and shouting, flashing, touching, grabbing, and transmission of pornographic images. 6 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm; HM Government (2010) Call to End Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy; Women’s Resource Centre (2008) Violence against women, health and the women’s voluntary and community sector. WRC:London 3 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Trafficking of women and girls, within the UK or across international borders Dowry-related violence. Female genital mutilation (FGM). Forced and child marriages. Crimes said to be committed in the name of ‘honour’. Sexual exploitation. Gender-based violence that intersects with other forms of social oppression, and which may not therefore be recognised as VAWG, but which in fact renders women more vulnerable to gendered forms of abuse and has gendered impacts in terms of women’s experiences and support needs. This includes, but is not limited to, physical, sexual, emotional and financial abuse of women who have physical, sensory or learning disabilities, mental health problems, insecure immigration status, do not have English as first language, and / or are homeless. Equality and Human Rights Perspective of Violence Against Women and Girls Human Rights. & Equality Act 2010 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) 1948 Article 3 “Everyone has the right to life and to live in freedom and safety” Article 4 “No one has the right to treat you as a slave nor should you make anyone your slave.” Article 5 “Everyone has the right to be free from torture and from inhuman and degrading treatment.” What are Human Rights? Human Rights are the basic rights we all have simply because we are human. They belong to everyone. Human Rights are based on our inherent human dignity; they are what it means to be human. Once people know their rights they can express their concerns with the confidence that they are backed by law. A Right “is something to which one is entitled solely by virtue of being a person … enables s person to live in dignity ….can be enforced ... and entails government obligation”. A need is an aspiration. Human Rights represent all that is important to us as human beings, such as being able to choose how we live our lives and being treated with dignity and respect. They cover many different aspects of everyday life, ranging from the rights to food, safety, shelter education and health, to freedoms of thought religion and expression. In a modern developed society 4 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) like the UK, human rights shine a spotlight on everyday issues, such as the poor treatment of older people in care homes, the rights of disabled people to live independently, violence against women and girls and the misused opportunities of children living in poverty. Human Rights place an obligation on the Sate to ensure that right is respected. Human Rights do not just cover the relationship between the Sate and the individual but also covers human relationships. The VAWG is covered by 3 main treaties The Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CCRC) Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) The Equality Act 2010. & Violence against Women and Girls The Equality Act 2010 helped to consolidate other and numerous equality based legislation. Under this duty public authorities are obliged to pay ‘due regard’ to the three aims of the law, Which are to: eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment and victimisation on the grounds of a protected characteristic; advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and those who do not; foster good relations between people who share a protected characteristic and those who do not. Having ‘due regard’ means consciously thinking about these aims within the process of decision making; Advancing equality of opportunity includes: removing or minimising disadvantages suffered by people due to their protected characteristics meeting the needs of people with protected characteristics encouraging people with protected characteristics to participate in public life or in other activities where their participation is low Fostering good relations involves addressing prejudice and promoting understanding between people who share a protected characteristic and others. Since women are a protected group, violence against them – the harassment and victimisation in the first aim of the duty – is a clear barrier to the achievement of equality: public bodies thus have 5 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) an obligation to consider it within their application of the duty. VAWG is also critical with respect the second and third aims - advancing equality of opportunity between women and men and promoting good relations between them. The latter suggests that a focus on prevention, changing the conducive contexts that allow violence to persist, and especially changing how men and boys perceive and treat women and girls, should be part of public policy thinking and decision making. The duty takes us further than this, since as it is a ‘single’ equality duty, and due regard must be paid to all protected characteristics, the experiences and needs of specific groups of women must also be considered (sometimes called ‘intersectionality’27). Consideration must, therefore, include: · older women girls; · disabled women; · black and ethnic minority women; · Lesbians, bi-sexual/polyamorous, and transgender. The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) have outlined six principles, based on case law, of which public authorities must be mindful, if they are to fulfil the Equality Duty. Knowledge: all involved need to be aware of the requirements of the Equality Duty: Compliance involves a conscious approach and open state of mind. Timeliness: the Duty applies before and at the time that any policy or decision is under consideration and should inform the development and exploration of options. It is not possible to satisfy the Equality Duty by justifying a decision after it has been taken if there is no evidence that it was not explored in the decision making process. Real consideration: consideration of the three aims of the Equality Duty must be integrated into the decision-making process and this must be exercised with rigour and with an open mind such that the exploration can influence the final decision. Sufficient information: those making decisions must assess what information they have, and what further information may be needed in order to give the Equality Duty real consideration. No delegation: public bodies are responsible for ensuring that any third parties which exercise functions on their behalf are capable of complying with the Equality Duty, are required to comply with it, and that they do so in practice. The duty cannot be delegated. Review: the Duty continues to apply when policies are implemented and reviewed; it is a continuing duty. 6 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) A Voluntary and Community Sector Guide to Using International Human Rights – Women’s Resource centre & British Institute of Human Rights Building Blocks A Strategy and Action Pan for Addressing Violence Against Women and Girls in Thurrock Liz Kelly and Maddy Coy March 2012 Why does VAWG happen? A gender analysis is crucial to understanding the causes of VAWG; the UN Declaration recognises that: “Violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women, which have led to domination over and discrimination against women by men and to the prevention of the full advancement of women, and that violence against women is one of the crucial social mechanisms by which women are forced into a subordinate position compared with men.”7 Unequal power relations between men and women persist within the UK and, in some areas; the gains towards equality that have been made by women are being reversed. 8 Discriminatory social and cultural norms contribute to violence against women and help to maintain attitudes of indifference and complacency towards it. 9 Such social and cultural norms and practices uphold gender power imbalances and include: social constructions of masculinity which privilege men and routinely devalue and objectify women; the notion that a man is ‘the head of the household’; the belief that violence against women is a ‘private matter between a man and a woman’; the glorification of violence against women in pornography and as popular entertainment; the sexualisation and objectification of women in the media and other forms of mainstream culture; ideas of male entitlement to sex and services from women; and codes of ‘honour’ and ‘shame’ which lead to violence being used towards women and girls.10 7 http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm The WRC report on Women’s Equality in the UK: a health check, which assessed progress made against the recommendations of CEDAW, found that equality is being eroded for all but the richest women in all areas of social, cultural, economic and political life. (WRC (2013) Women’s equality in the UK – A health check. Shadow report from the UK CEDAW Working Group assessing the United Kingdom Government’s progress in implementing the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)) 9 Council of the European Union Council Conclusions on Combating Violence Against Women, and the Provision of Support Services for Victims of Domestic Violence. 6th December 2012. 10 See for example: Jeffreys, Sheila (2005) Beauty and Misogyny: Harmful Cultural Practices in the West, London: Routledge; Cerise, S. (2011) A Different World is Possible: A call for long-term and targeted action to end violence against women and girls; Roy, S., Ng, P, Larasi I., Dorkenoo, E., and Macfarlane, A (2011) The Missing Link: A joined up approach to addressing harmful practices in London. Imkaan/ City University, London; Dustin, H, and Shepherd, H (2013) Deeds or Words? Analysis of Westminster Government action to prevent violence against women and girls. London: EVAW 8 7 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) There are commonalities and connections between all forms of violence against women, which include: the abuse of male power and privilege; myths and stereotypes used to minimise or justify the abuse and excuse the perpetrator; the gender dynamics of power and control; high levels of under-reporting and low conviction rates; the extent of repeat victimisation; the long-term social, psychological and economic consequences for victims/survivors and the failure of many governments to adequately address gendered violence.11 The widespread attitudes that excuse and condone violence against women and girls have been evidenced by a number of research reports; for instance: 36 per cent of people believe that a woman should be held wholly or partly responsible for being sexually assaulted or raped if she was drunk, and 26 per cent if she was in public wearing ‘sexy’ or revealing clothes. One in five people think it would be acceptable in certain circumstances for a man to hit or slap his female partner in response to her being dressed in sexy or revealing clothing in public. Almost half (43 per cent) of teenage girls believe that it is acceptable for a boyfriend to be aggressive towards his partner. 1 in 2 boys and 1 in 3 girls believe that there are some circumstances when it is okay to hit a woman or force her to have sex. 12 Nearly half of people believe that domestic violence is something that happens behind closed doors and is for the partners to sort out [ICM (2003) Hitting Home BBC Domestic Violence Survey]. More people would call the police if someone was mistreating their dog than if someone was mistreating their partner (78% versus 53%) [ICM (2003) Hitting Home BBC Domestic Violence Survey].13 In a survey of 103 UK men who buy sex, 25% said the concept of rape does not apply to women in prostitution.14 The same survey found that the majority of the men questioned (55%) were aware that many women in prostitution may have been tricked, lured, coerced, exploited or trafficked, but that did not affect their decision to buy sex. 11 Coy. M. et.al. (2008) Realising Rights, Fulfilling Obligation. End Violence Against Women Coalition Cited in Cerise, S. (2011) A Different World is Possible: A call for long-term and targeted action to end violence against women and girls.p.5. London: EVAW 13 Cited by the AVA (Against Violence and Abuse) project http://www.avaproject.org.uk/ourresources/statistics/society%E2%80%99s-attitudes-to-violence-against-women.aspx 14 Melissa Farley, Julie Bindel and Jacqueline M. Golding (2009) Men who buy sex: Who they buy and what they know. A research study of 103 men who describe their use of trafficked and nontrafficked women in prostitution, and their awareness of coercion and violence. Eaves, London 12 8 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Blaming the victim is something that abusers will often do to make excuses for their behaviour. This is part of a pattern of impunity and is in itself abusive. Perpetrators, communities and wider society often attempt to excuse violence against women by focussing on the behaviour of the victim or on other factors such as his childhood, ill health, poverty, and alcohol or drug addiction. In this way, the perpetrator avoids taking responsibility for his actions and his behaviour is explicitly or tacitly condoned.15 A holistic and integrated approach to addressing VAWG This strategy connects all forms of VAWG within a coherent gendered analysis; bringing together separate initiatives on sexual violence, domestic abuse, trafficking, FGM, forced marriage, prostitution, stalking, so called 'honour' based violence and murder (femicide) in one document. This approach will enable us to develop policies, resources and responses that encompass violence that takes place within family, domestic and care-giving settings as well as beyond these, whether relating to current and on-going violence or to historic abuse, and which recognises the cumulative impact of repeated and different forms of abuse. Many women will experience multiple forms of gender-based violence throughout their lives, and by understanding that different types and acts of violence form part of a continuum, the overlaps and connections between them become clear.16 For example: Domestic violence includes not just physical assaults but also sexual abuse, exploitation and manipulation, emotional and psychological abuse, financial abuse and stalking: most stalking takes place post-separation. Some women are forced into prostitution by abusive partners. There is a wide body of research that documents links between domestic violence and child abuse, including child sexual abuse, which in turn is associated with early entry into the sex industry and sexual exploitation.17 Forced marriage is linked to rape, forced pregnancy, forced child-bearing and other forms of violence. Violence carried out in the name of ‘honour’ in its most extreme forms leads to the murder of women.18 Women’s Aid (2009) Domestic Violence: Frequently Asked Questions. Factsheet; Understanding Gender Inequality and Violence against Women Training Pack’. (2010) Argyll and Bute Community Planning Partnership / Women’s Support Project; DFID (2012) A Theory of Change for Tackling Violence against Women and Girls. CHASE Guidance Note 1 16 Kelly, L and Coy, M (2012) Building Blocks: A Strategy and Action Plan for Addressing Violence Against Women and Girls in Thurrock. London: CWASU 17 Kelly and Coy (2012) (op.cit.). 15 9 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Certain groups of women are more vulnerable to being victims of multiple forms of gender-based violence: in particular, adolescents; young women; women with physical disabilities or learning disabilities; women with mental health issues; homeless women; women who sell sex; those living in institutions such as hospitals and temporary accommodation; Traveller women; women in areas of conflict / war situations and those who are asylum seekers and refugees.19 This vulnerability is likely to be understood by many people as linked to women’s situations, lifestyles and/or abilities, but much more emphasis needs to be placed on the targeting strategies of violent, coercive, predatory and manipulative men. That is, the men who choose to target and victimise those women and children who have few resources to resist and who are less likely to be believed or taken seriously should they report.20 Reporting Many women and girls choose not to report the violence they are experiencing, or have experienced, to agencies, especially statutory organisations. There are many reasons for this, ranging from not defining what happened as abuse, fear of reprisal from the perpetrator or the community, feelings of stigma and shame, fear of not being believed, through to distrust of the agencies themselves. 21 Whilst awareness 18 Roy, S., Ng, P, Larasi I., Dorkenoo, E., and Macfarlane, A (2011) The Missing Link: A joined up approach to addressing harmful practices in London. Imkaan/ City University, London 19 Gill, A (2013) ‘The Oxford abuse case and the myth of the “good girl” victim’ The New Statesman, 15/5/13; Barter, C, McCarry, M, Berridge, D and Evans, C (2009) Partner exploitation and violence in teenage intimate relationships www.nspcc.org.uk/inform; McCoy, E, Jones, L and Quigg, Z (2011) A consultation with young people about the impact of domestic violence (abuse) in their families and their formative relationships. Liverpool John Moores University; Hague, G, Thiara, R., Magowan, P (2007) Disabled Women and Domestic Violence: Making the Links. An Interim Report for the Women’s Aid Federation of England; Anitha, S (2011) ‘Legislating Gender Inequalities : The Nature and Patterns of Domestic Violence Experienced by South Asian Women With Insecure Immigration Status in the United Kingdom’ Violence Against Women, 17(10) 1260– 1285; Dorling, K, Girma, M and Walter, N (2012) Refused: the experiences of women denied asylum in the UK. Women for Refugee Women; WNC (2009) Still We Rise: Report from WNC Focus Groups to inform the CrossGovernment Consultation “Together We Can End Violence Against Women and Girls” 20 Kelly, L (2005) Promising Practices addressing sexual violence. Expert Paper delivered by Professor Kelly, Child and Woman Abuse Studies Unit, London Metropolitan University, at: "Violence against women: Good practices in combating and eliminating violence against women" Expert Group Meeting Organized by: UN Division for the Advancement of Women in collaboration with UN Office on Drugs and Crime 21 Parmar, A., Sampson, A. & Diamond, A. (2005) Tackling Domestic Violence: Providing Advocacy and Support to Survivors from Black and Other Minority Ethnic Communities; RASASC (2011) Reporting sex offences, RASASC Research and Policy Bulletin 7/08/11: http://www.londoncouncils.gov.uk/London%20Councils/RASASCResearch2011CarolMcNaightonNich olls.pdf; Walby S and Allen J (2004) Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault and Stalking: Findings from the British Crime Survey. Home Office Research Study 276. London: Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate. 10 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) raising and improved responses can remove some of these barriers, there will always be some women who choose to remain silent and only seek support later in life. Others will decide not to pursue a criminal case, but to approach specialist VAWG organisations which offer confidential services. Unless someone else, especially a child, is at risk, the decisions women make about who to report to and when should be respected. Consequently, the voluntary sector and women-only organisations which so many women turn to so as to disclose violence and to seek support should be prioritised within local planning processes. Empowerment Empowering women and girls is the core aim of this strategy, as focusing on the rights of women and girls is the most effective way of combating gender inequality as the root cause and consequence of gender-based violence. 22 Research and practice shows that building and expanding women’s and girls’ resources, knowledge, confidence, choices and agency is critical to transforming unequal power relations and preventing violence against women and girls.23 Additionally, all relevant agencies and services need to ground their work in an understanding that violence takes away the ability of the victim to control her own body, personal autonomy and life. Repeated violations fundamentally undermine her sense of self and trust in other people. To be assaulted and violated is to have power used against you; which explains the importance of ‘empowerment’ in all interventions. It does not reinstate the power of women and girls who have been victimised to take decisions for them. Survivor/service user consultation groups and other methods of engagement are an important and effective mechanism for giving women a voice, thereby ensuring survivors’ views and needs are at the centre of policy and inform practice.24 Women-only services have been found to be crucial to providing safe spaces outside the male dominated mainstream and for facilitating women’s empowerment.25 A key benefit of women-only services is physical and emotional safety, which is vital for the 22 World Health Organisation (2009) Violence Prevention: The evidence. Promoting gender equality to prevent violence against women, Geneva: World Health Organisation / Centre for Public Health, LJMU 23 Abrahams, H (2007) Supporting Women After Domestic Violence: loss, trauma and recovery. London: Jessica Kinglsey Publishers; Craven, P (2008) Living with the Dominator. Freedom Publishing; Kelly, L (2005) Promising Practices addressing sexual violence. Expert Paper delivered by Professor Kelly, Child and Woman Abuse Studies Unit, London Metropolitan University, at: "Violence against women: Good practices in combating and eliminating violence against women" Expert Group Meeting Organized by: UN Division for the Advancement of Women in collaboration with UN Office on Drugs and Crime 24 Kelly, L and Coy, M (2012) Building Blocks: A Strategy and Action Plan for Addressing Violence Against Women and Girls in Thurrock. London: CWASU 25 Women’s Resource Centre, (2010) Power & Prejudice: Combating gender inequality through women’s organisations, London: WRC; Women’s Resource C entre (2011) Women-only services: making the case. A guide for women’s organisations. London: WRC 11 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) development of confidence, greater independence and higher self-esteem. Womenonly services help women become less socially isolated and marginalized, particularly as some women who would not attend mixed services would not receive a service if there were not women-only services. We therefore support the prioritisation of women-only support services, as well as broader women’s rights and empowerment initiatives, as a key means of addressing the root cause and consequences of violence against women and girls. Prevention. Prevention and early intervention of violence and abuse of women and girls is a vital and key ingredient of the VAW&G strategy. Investment in prevention and early detection will save a great deal in terms of lives lost, physical and psychological hurt, family breakdown and complex needs. Many services are geared to react to women and girls once they have made a complaint. In many cases once disclosure has been made the abuse is well established. In an economic sense saving lives, preventing injury and mental anguish will save valuable resources. To investigate, send to trial and convict a murderer costs the criminal justice system £1million 1. This does not take into account the lives broken by the murder, the effect on family and other service providers. National Picture 2 • Around 2 million women suffer domestic abuse • 536,000 victims of sexual violence offences • 95,000 victims of rape • Only 1 in 4 domestic offences are reported to police • Only 1 in 10 sexual violence offences • 20% of rapes reported to police • 1186 referrals nationally to UK Human Trafficking Centre (480 for sexual exploitation). None from Merseyside or Liverpool • Top 5 nationalities referred to UKHTC were Nigeria, Vietnam, Albania, Romania and China. Just over 9000 Liverpool residents (male & female) are of these nationalities 1. Baroness Scotland Domestic Abuse Conference November 30th 2013 2. Data collected by City safe 2013 12 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) • To date there have been no prosecutions in the UK for FGM however there have been more than 1,700 victims of FGM have been referred to specialist health clinics in the UK in the past two years The key parts to prevention are as follows Awareness – of the problem what to look out for, asking the right questions and being aware of services that can help the referral pathways. Being non-judgemental and engendering trust. Many service providers are unaware of the cost to society of the violence and abuse, what signs to look out for, with adults and children, daring to ask the question about the abuse and understanding the referral pathways once the individual has disclosed what is happening to them. To send a person away under such circumstances, to then find out what to do, is not an option. To ensure that when service providers are approached for help they are not judgemental. Education – is key. To talk to the young about concepts such as love, healthy relationships, what it means to be a man, masculinity and being female.;what help is available, and that abuse if happens is not “normal” or acceptable; tackling early indications of behaviour that could lead to abuse, for example anti-social behaviour, bullying and abuse; tackling stereotypes. Media, Stereotypes & Sexualisation of Girls – Media can purvey harmful stereotypes, which can influence the young. Sexting in schools is becoming commonplace in Liverpool. The porn industry sexualises our children and objectifies the female gender. There is a need to recognise the effect porn has on the minds of young people, educate against stereotypes. Also to explore with the media & porn industry ways of regulation that protect against hostile attitudes. Empowering of Young Women – Raising aspirations and providing young women with a goal in life to attain and selecting the support they need to obtain their ambitions. Partnership working – Services on prevention need to be joined up both from an operational level and strategically. Services are working successfully as part of the MARAC, but the MARAC deals with high-risk domestic abuse cases and not prevention. “An Agreed set of common messages about VAW&G across stakeholders will enable less visible outcomes to be recognised and factored into local decision making. Consensus on both the necessity of prevention work and the key messages to be communicated is vital” 3. 3. Thurrock Violence against Women and Girls Strategy by Liz Kelly 13 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Mapping of Services – of what is available where, how these are accessed and what the gaps are Raising Awareness of services – so that the public and key service providers know of their existence and how they can refer. Research – Examining what is happening elsewhere and looking at good practice. Monitoring – Looking at facts and figures, experiential data, social return on investment and cost benefit analysis. This is to look at the investment in prevention services and estimate how vital resources can be saved. Protection. In terms of public policy and international law, there is a duty to protect women and girls from violence and abuse. Protection covers immediate safety for those suffering from all forms of violence and for those provisions to be accessible. Protection also covers early intervention to prevent issues such as FGM and forced marriage. It is important for agencies to be aware of such practices and provide women and girls with the right environment to say what is happening to them, or what they have been threatened with. There are issues around public space and safety for women and girls to carry out their everyday action without fear of abuse or crime. This aspect needs to be factored into decisions such as planning, neighbourhood and city centre management, the environment and transport plans. Protection also covers important facilities such as support Networks & MARAC Risk Assessments and Action Planning. Civil Law protection orders and offender mismanagement systems are formalised systems of protection. To help protect women and girls, the victims need to be believed and treated in a in a non discriminatory way. Provision. Unfortunately, Violence against women and girls is on the increase in Liverpool, Last year there were statistic 33,261 calls about VAW&G in Merseyside. Nationally the police receive a call about DV every 30 seconds. (2) This has to be offset with serious cut backs in public and voluntary sector provision. Yet if services that help provide for and prevent sexual and violent abuse are cut, in the medium and longer term this could cost the state, communities and families more. Baroness Scotland, in a conference in Liverpool in November 2013, highlighted the improvements that joint agency working and the MARAC had over the last 10 years in London. (1) 14 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) By 2009 in the UK Domestic Violence had been reduced by 64 %. In 2003, when I started, there were 49 deaths due to Domestic Violence in London. When I left in 2010 that number had been reduced to just 5 deaths. Every death cost us as a Criminal Justice System, if there were no children involved, £1.1 million at least. Therefore that reduction has resulted in a saving to London if you are only interested in how to reduce the deficit, of £44 million. In human and economic terms the change has been dramatic. The research in 2004 by the Department of Trade and Industry had demonstrated that Domestic Violence was costing us £23 Billion. In 2009 that was reduced to £15.5 billion, a saving of £7.5 billion per year in just five years. The changed way of working had significantly reduced the deaths of women and girls and by doing so had saved millions pounds of resources that would have been put into a murder or manslaughter investigations and trials. Good provision is vital, but also is the need for agencies to come together to share information, risk assess and action plan. Arguably for both the victim and offender. As a result of sustained abuse, many women suffer both mentally and physically. On average the amount spent per year on mental health services is £176 million and on providing care following physical injuries £1.2 Billion a year cost the state (3). It is of concern that services are being cut that help women and girls with regard to violence and abuse. This has been shown in 2013 Women at the Cutting Edge, which takes a gendered perspective of the cuts in provision to women and girls. There are fears around the IDVA service, lack of funding for one-to-one counselling or cuts in places to the Freedom Programme. Specialist services and provision are key to help prevent and stop future abuse. Liverpool: 33,261 incidents reported to the police in 2012 -13. 4.4% conviction rate. Source here: http://www.theguardian.com/society/datablog/2014/mar/10/domestic-abuse-sexual-violence-what-the-newfigures-tell-usMerseyside had one of lowest conviction rates It is vital that services that are commissioned are women-only, specialised services. In a recent study by Liverpool Mental Health Consortium Sub Group What Women Want Group on Domestic Abuse and Mental Health, it was found that many women will not speak to a man or use services that include men. In cases of BRM woman, to quote one voluntary’s sector provider: “iIf they see a man they will turn round and leave our services”. (2) The specialist counselling and care provided is not currently provided by the police or mainstream mental health services. In many cases Women and Girls slip through the net of more generalised services such as GP’s or generalist counselling, who do not recognise or ask about the cause of the presenting illness. In a study conducted in 2009 of focus groups with 209 women, many women were put off seeing their GP’s by receptionists acting like gate keepers demanding to know what the women wanted from the GP’s.(3) This strategy confirms the findings of the Domestic Abuse & Mental Health research conducted by the Liverpool Mental Health Consortium Subgroup What Women Want Group March 2014 The findings are worked into the action plan and 15 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) support the need for specialist, women-only, adequate provision. .( Link to report www.liverpoolmentalhealth.org/_wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Domestic-Abuse-MentalHealth-LMHC-20141.pdf There needs to be a diversity of provision of services to take account of the different forms of violence , to provide intervention in crisis, longer term help, to take into account women’s and girls’ other protected characteristics, such as ethnic original, impairment or age., as well as access for women with complex needs, the accessibility of provision and how women find out about what support they could get. Provision should include helplines, shelter, advocacy, medical support, counselling and other forms of support. Women-only, specialist provision is key to helping women and girls to come forward. Finally it is important that the quality of services and how those services are delivered is crucial. They should be non-discriminatory in their delivery; that achieves the right outcome: that women and girls are safe and perpetrators are dealt with. In a recent report to Teresa May, there were serious concerns in the way the police are handling domestic violence cases. The Guardian report highlights the following “The report said there were alarming and unacceptable weaknesses in core policing activity, in particular in the quality of the initial investigation. It also raised serious concerns over the failure of the police to undertake risk assessments of victims – with a confused approach to arrests of alleged perpetrators.” (3) Despite cutbacks in service, there is a need to ensure that when an agenc,y public or voluntary, delivers a response to a victim of violence or abuse, it is of the best quality and outcome possible. Perpetrators & Prosecution Violence against Women and Girls strategy is addressing violence and abuse from a gendered perspective. As a result of this and the fact that the majority of violent crimes are perpetrated by heterosexual men, the strategy looks at the need for dealing with perpetrators and not putting the problem in the “too-difficult-to-do tray.” Colleagues in the MARAC have commented on the number of cases that have recurred due to repeat offenders. The victims are “protected”; the perpetrator sometimes goes to gaol, only to later find that the perpetrator is back harming another or the same women or girl. There is a vicious cycle of abuse. Arguably, perpetrators should be dealt with as law breakers, but also educated to stop the offence reoccurring with another potential family. Domestic Abuse is not a crime in this Country and as such Police are reliant on criminalising the symptoms of the abuse instead of tacking the systematic and protracted cause of the abuse. In Scotland a specialised enforcement agency has been set up to deal with perpetrators. 'In Scotland, elite teams have been set up to deal with domestic abuse in the same way that a homicide would be investigated.' (3) 16 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) In the wake of Her Majesty's Inspector of Constabulary's damning report exposing "alarming and unacceptable weaknesses" in the way police respond to domestic violence in England and Wales, force chiefs may want to cast their eyes across the border. In Scotland, the term "domestic violence" is no longer in use and is referred to officially as "domestic abuse", because verbal attack and controlling behaviour can be used to subjugate a victim to the perpetrator's will. In a recent report to the Home Office police forces have been severely criticised about the way they handle domestic abuse. “Theresa May will lead a national oversight group to ensure chief constables act on the recommendations of Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), which she described as "depressing reading". The inspectorate condemned the police service for treating domestic abuse as "a poor relation" to other police activity – and concluded that only eight out of 43 forces responded well to domestic violence” (5) One of the chief actions of this strategy will be to look at the recommendations put forward by the report and see if the good practice can be followed in Liverpool. Education There are voluntary education schemes in operation for men who are perpetrators; there is one in Merseyside, for example, called “Help.” The main problem seems to be that men, for whom the course was designed, do not attend. Perhaps there is sense in making the course obligatory and using gaol terms as a venue of delivering the course. Also the course should be evaluated to see if it is working. There is a need for looking at boys and putting in place provision that helps educate our young men about relationship violence and abuse: to start questioning what is traditionally regarded as Masculinity. Link with Hate Crime In a recent study by Roehampton University, the researchers questioned whether Domestic Abuse should be classified as a hate crime. It was felt this would increase the tariff for offenses and raise the profile for domestic abuse, which is not currently defined as a crime. The outcomes of the report highlighted misgivings about creating complexities around implementing the change in law, but said: “ There was general support for the inclusion of a gender category in hate crime legislation on the basis that it would challenge mistaken assumptions and problematic stereotypes and (ii) it would encourage the issue to be taken seriously.” (3) In a recent meeting of the Community Cohesion and Hate Crime Subgroup December 2013, it was recommended that further consideration should be given domestic violence cases, where there is clear evidence of misogyny, for example by looking on the computer hard drive for evidence, and where the victim had been subject to abuse due to her protected characteristic, which classifies the abuse as hate crime; currently, these characterises are Race, Disability, Gender identity, Sexual orientation, and faith. 17 VAWG Task and Finish Group (LWN/ Citysafe) Enforcement agencies need to address offending behaviour even if the VAW&G is seen as a lesser part of a “more serious” charge; there is a need for risk assessing perpetrators, information sharing and monitoring perpetrators. (1) Guardian Report 27th March 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/27/scotland-domestic-abusebritish-police-forces (2) The Guardian 27th March 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/mar/27/police-failures-domestic-violencedamning-report (3) Eliminate Domestic Violence Rt Hon Baroness Scotland of Asthal QC BY Robin Marsh 16th December 2011 http://uk.upf.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=414:eliminate-domesticviolence-rt-hon-baroness-scotland-of-asthal-qc-&catid=59:2008&Itemid=108 (4) Domestic Abuse and Mental Health Conference 28th March 2014 (5) Map of Gaps The Post Code Lottery of Violence Against Women Support Services in Britain (6) Department of Health (8)Addressing Violence as a form of Hate crime: limitations and possibilities Feminist Review Aisha K Gill Na d Hannah Mason - Bash Comments to Gail Jordan LCVS tel 0151 227 5177 or email gail.jordan@lcvs.org.uk 18