The Adoption of Human Resource Management Practices

advertisement

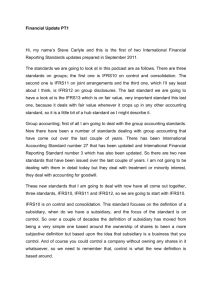

The Adoption of Human Resource Management Practices &Perceived Performance of Foreign Subsidiaries Dr Maura Sheehan Reader University of Brighton EU Marie Curie Scholar, 2009-2012 UFHRD Conference Chair, Brighton, 2013 m.sheehan@brighton.ac.uk Stream 2: Full Paper Abstract Set within the framework of institutional theory, this paper examines the implications of the transfer of Human Resource Management (HRM) practices, including management development (MD), for perceived performance in subsidiaries of multinational corporations (MNCs). It is found that the mere presence of HR practices does not fully capture the more nuanced nature and extent of transfer and the associated relation to perceived subsidiary performance. A positive association is found between a greater number of HR practices (the presence of practices) and perceived subsidiary performance. The interaction of high levels of implementation and internalisation was very significantly associated with better perceived subsidiary performance than the presence of more practices. Finally, analysis of the relation between adoption typologies and perceived subsidiary performance found a positive and very significant association between ‘active’ adoption and perceived subsidiary performance; a positive and significant relationship for subsidiaries where adoption was in ‘assent’; and no significant relationship where there was ‘ceremonial’ or ‘minimal’ adoption. The analysis is based on data from multiple respondents (a HR Specialist/Manager and a line manager) in foreign subsidiaries of UK-owned MNCs. Keywords: Human resource management; implementation and internalisation; transfer of HR practices; multinational corporations (MNCs); perceived subsidiary performance. 1 Reviews of the human resource (HR) – performance relationship (see, for example, Boselie, Dietz & Boon 2005; Combs, Ketchen, Hall & Liu, 2006; Guest, 2011) find an association between a greater number of HR practices and various indicators of organisational performance. Despite the vast number of empirical studies on the HR- performance relationship, few studies have examined whether this relationship applies within subsidiaries of multi-national corporations (MNCs). A notable exception, Foley, Ngo & Loi (2010), find that the use of high performance work systems (HPWS) did indeed have a positive association with the performance of foreign subsidiaries based in Hong Kong. There remains, however, a dearth in the understanding of how this HR-performance relationship operates. The process perspective tries to answer this by examining the ‘how’ question, i.e., how is organisational performance achieved through HR management? (Sanders & Frenkel, 2011). While this is a relatively new research area in the context of the HR-performance literature, the importance of process– especially HR practice transfer and adoption - has already received considerable attention in the international human resource management literature (e.g., Collings & Dick, 2011; Kostova & Roth, 2002). Increased globalisation, especially the ever rising flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) into emerging economies, has been a driving force behind the emergence of the literature which seeks to understand the extent, determinants and process of, management practice transfers. Given the importance of human resources for sustained competitive advantage, MNCs utilise advanced and sophisticated practices and systems. These HR practices are viewed as valuable resources or competences that managers are likely to seek to replicate, by transfer, throughout the organisation (Szulanski, 1996). Consistency in HR practices can also contribute to developing a common corporate culture, enhancing equity and procedural justice within the MNC (Kim & Mauborgne, 1993), managing external 2 legitimacy of the MNC as a whole (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), and facilitating the transfer of employees within the MNC - essential for successful global talent management (McDonnell, Lamare, Gunnigle & Lavelle, 2010). There is, however, considerable evidence that shows planned transfers of practices (in particular, their internalisation and implementation) do not always occur in ways anticipated or desired by corporate headquarters (HQs), with transfer even varying between subsidiaries belonging to the same MNC (Kostova & Roth, 2002). Theoretical models (e.g., Björkman & Lervik, 2007) and empirical studies (e.g., Kostova & Roth, 2002) have explored factors that help to explain why there are differences between MNC subsidiaries in the extent to which they adopt HR practices that MNC headquarters attempt to transfer. This paper brings the HR-performance and HR-transfer literatures together. Specifically, the paper extends the extant literature by examining the potential role of implementation and internalisation of HR practices, and their associated adoption typologies, for the perceived performance of foreign subsidiaries of MNCs. A multi-respondent approach is used to examine these relationships. In particular, the analysis is based upon responses from the HR Specialist/Manager and line manager based at a foreign subsidiary of UK-owned MNCs. Since the performance data are self-report, the term ‘perceived performance’ is used throughout the paper. To control for potentially significant ‘country of origin’ effects, the study focuses on UK-owned subsidiaries only. All of the foreign subsidiaries are based within the European Union (EU) and within one region, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). During the last decade, and especially since the enlargement of the European Union (EU) in May 2004, the CEE region has been a significant 3 recipient of FDI flows and is an important emerging region on the global economic landscape (OECD Statistics 2009).1 Moreover, a focus on one region within the EU enables potentially important institutional differences to be examined whilst not introducing vast institutional heterogeneity into the sample. The next section reviews the relevant literature which provides the basis for the paper’s hypotheses; the research methodology and the sample are then described; the results are presented which is followed by a discussion; the paper concludes with a discussion of its limitations and directions for future research. LITERAUTURE REVIEW & HYPOTHESES Theoretical Background Institutional theory has been widely used to study the adoption and diffusion of organisational practices, including HR practices, within, and across organisations (Farndale & Paauwe, 2007; Kostova & Roth, 2002). By focussing on external environmental forces, institutional theory helps to explain evidence of homogeneity or convergence of HR practices, sometimes placed in a framework of universalism or ‘best practice’. According to the ‘best practice’ perspective, particular HR practices improve the opportunities for 1 The data analysed are part of a wider EU-funded study that examines the determinants of foreign direct investment(FDI); the role and functions of human resource management; and subsidiary level performance in three Central Eastern European Countries: Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. With the notable exception of Morley, Heraty & Michailova (2009), little is known about HR in this important emerging region. 4 workplace participation, motivation and/or abilities, leading to higher work and organisational performance. Competitive isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) assumes a system of economic rationality, which emphasises the pressures exerted by market competition and the need for economic legitimacy, as drivers of similarity. Competitive isomorphism would predict that corporate HQs of MNCs would seek to transfer ‘best practice’ HR to their subsidiaries to benefit from associated efficiency gains. Thus, based on the assumption that there is likely to be a high level of transferred HR practices with the objective of increasing subsidiary efficiency, the first hypothesis posits: Hypothesis 1: There will be a positive association between the presence of (more) HR practices and perceived subsidiary performance. However, competitive isomorphism,especially if set in a context of ‘best practice’, is constrained by both its time-limited source of advantage because once a critical mass of organisations within a given field is doing the same activities, initial competitive advantage will dwindle, or cease. The ‘best practice’ approach is also widely criticised for being too prescriptive (Purcell & Kinnie, 2007). Moreover, in the context of the HR-performance debate, the best practice approach tells us little about the processes that join HR practices to improved performance. A less prescriptive approach is provided by the best-fit (or contingency) approach which focuses on adapting HR practices to the prevailing political, cultural and/or economic environment. While rooted in institutionalism, it is closely related to DiMaggio & Powell’s (1983) second type of isomorphism: institutional isomorphism and three associated mechanisms which may influence decision making in organisations. In the context of HR, the 5 first mechanism – coercive - includes the role of social organisations, who may be partners (e.g., trade unions and works councils), employment legislation and the government. The mimetic mechanism refers to a firm’s benchmarking strategies and HR practices against each other, and copying practices which are viewed to deliver desirable outcomes. Normative mechanisms include the impact of HR professional bodies and employer associations on the adoption of agendas, terminology, and practices of current importance. It is essential, however, that these mechanisms are not treated as deterministic, in the sense that organisations are viewed as passive agents in the interaction with the institutional environment (Wailes, Ramia & Lansbury, 2003). Indeed, the literature on HR diffusion in MNCs sees institutionalisation as a ‘contested process’ and subsidiaries of MNCs, as ‘contested space’ (Edwards, Colling & Ferner, 2007). The emerging micropolitical approach focuses on the role that power relationships within MNCs, particularly between corporate headquarters and local level managers, play in shaping the HR diffusion process (Edwards et al., 2007; Ferner, Almond, Clark, Colling, Edwards, Holden & Muller-Carmen, 2004). Managers in subsidiaries may resist the transfer of some MNC practices that disrupt the current division of labour, or relations with other agents or stakeholders such as trade unions, or those that do not fit with the local institutional context. Managers may use their embeddedness with the local and/or national context to contest the implementation of corporate HR policies. Indeed, there is now considerable recognition of the potential for agency to exist in the institutional theory of the firm, and its capacity to moderate and mediate the transfer of employment practices and the process of delivery. Managers have considerable scope for agency. In particular, they have the ability to spend more time on activities they consider 6 important and/or are reviewed and rewarded on, and less time on those that they find unimportant, and/or are not reviewed/rewarded on (Konrad, Waryszak, & Hartmann, 1997). The relationship between HR managers/specialists and line managers in MNCs is a complex one because both are ultimately agents of HQs. Not only is there scope for individual agency, scope also exists for ‘inter-agency’ conflict (e.g., between HR, IT, marketing, and line managers) - especially in the periphery and, even more so, when the periphery operates in an institutional environment that is different from, or unfamiliar to, the principles based in the core (Regner, 2003). Thus, while the pressures of distinct institutional frameworks may exert strong forces for the transfer of practices and processes, the indeterminacy generated by the inter-play of the micropolitical environment of foreign subsidiaries, the potential scope for considerable agency and inter-agency conflict - are likely to influence the implementation and internalisation of transferred HR practices - which is likely to result in a divergence between intended practices and the reality of the processes associated with their delivery. The HRM-Performance Relationship and links to Practice Transfer and Adoption The link between HRM and firm performance has been a dominate theme within much of the HRM literature since the mid-1990s and while the HRM-performance relationship has been examined in many different national contexts, few studies have examined the relationship between HRM and performance within subsidiaries of MNCs (see Foley et al., 2010 for a notable exception). However, a simple count of HR practices (often estimated by an index) is likely to be a highly inadequate way to explore the relationship between HRM and subsidiary performance. As noted by Purcell & Hutchinson (2007: 3): “It is often observed that there is a gap between what is formally required in HR policy and what 7 is actually delivered...” This potential gap between the rhetoric and reality of HR is of particular relevance in the context of MNCs, given complex issues associated with transfer, already discussed. Thus, while a particular HR practice may formally be recorded as ‘in place’ by corporate HQs and even by the subsidiary, if it is not implemented, or only minimally so, then its’ association with performance may be negligible. In addition, if a practice is not implemented, it is unlikely to be internalised. Thus, it will be important to examine whether there is a relationship between each of the two types of transfer and perceived subsidiary performance. Indeed, the concepts of implementation and internalisation are central to understanding the process of transfer. Implementation is the empirically observable behaviours constituting the enactment of the transferred practice (Kostova & Roth, 2002). For example, if the transferred HR practice was 360 degree feedback, one would observe it being operationalised which would be reflected in associated behaviours and actions of all employees to whom the practice was intended by HQs to apply (e.g., all managerial employees). Importantly, the concept reflects the extent to which HQs prescriptions, arising from desired efficiency, coordination and/or legitimacy in the MNC as a whole, are enacted by subsidiaries. Internalisation reflects the degree to which externally imposed rules become internalised in the recipient unit. Specifically, the transferred practice, e.g., variable pay, is taken for granted and accepted by employees. If internalisation has taken place employees see the value of using the practice and are committed to sustaining its delivery (Kostova, 1999). In other words, the mere presence of HR practices does not necessarily mean that they have been implemented and/or internalised - both of which are likely to be key processes that will affect the strength of the HR-performance relationship. Thus, hypothesis 2 posits that: 8 Hypothesis 2(a): The implementation of practices will have a greater association with perceived subsidiary performance than the presence of (more) practices; and Hypothesis 2(b): The internalisation of practices will have a greater association with perceived subsidiary performance than the presence of (more) practices; and Hypothesis 2(c): There will be a positive interaction between higher implementation and internalisation and perceived subsidiary performance. The analysis of the interaction between the types of HR transfers can be extended by examining adoption typologies. Kostova & Roth’s (2002) adoption typologies which reflected the interaction between implementation and internalisation are used in this analysis (see Figure 1). Insert Figure 1 around here Where there is minimal implementation and internalisation the adoption is ‘minimal’; where implementation is high but internalisation is low then there is likely to only be ‘ceremonial’ adoption; where there is low implementation but high internalisation, the adoption of the practice is likely to be in ‘assent’; and where there is both a high level of implementation and internalisation there will be ‘active’ adoption. The adoption typology present in a subsidiary reflects a key process of HR delivery and is also likely to influence the ‘strength’ of the HR system (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004). It is expected that where there is ‘active’ HR transfer - the full benefits of HR practices should be realised which is likely to be positively associated with performance. In contrast, where transfer is ‘minimal’, the benefits associated with HR practices are likely to be low and the costs associated with minimally adopted practices may actually result in a 9 negative association with performance. While ‘ceremonial’ and transfer that is in ‘assent’ indicate that HR practices have not been fully transferred, which is likely to mean that practices are not utilised to their full potential, these two typologies may reflect the forces of institutional dualities and some compromise between local and global tensions (e.g., Collings & Dick, 2011). Such types of transfer may be appropriate, at least in the interim, especially if they help to minimise any perceptions of coerciveness among subsidiary employees. Nevertheless, the presence of these two typologies is likely to weaken the HR-performance relationship. Based on this analysis, hypothesis 3 examines the relationship between HR adoption typology and perceived subsidiary performance: Hypothesis 3(a): High levels of both implementation and internalisation (an ‘active’ transfer typology) will have the most positive and significant association with perceived subsidiary performance compared to other transfer typologies; and 3(b): Low levels of implementation and internalisation (a ‘minimal’ transfer typology) are not expected to be significantly associated with perceived subsidiary performance and the relationship may indeed be negative. No a priori assumptions are made for the typologies of‘in assent’ or ‘ceremonial adoption’. Thus, while competitive isomorphism suggests that there is likely to be a high number of HR practices transferred to MNC’s subsidiaries, with the objective of enhancing efficiency, institutional isomorphism - especially if active agency and inter-agency conflict is present suggests that the process of HR delivery is likely to differ from how the practices were intended to be delivered by HQs. Any difference between transfer and the process of delivery is likely to affect any HR-performance relationship that may be found. 10 METHODS Research Framework Given the potential for a divergence of perspectives, especially about perceptions of HR transfer, input was from two respondents - the HR Specialist/Manager and a line manager - within the foreign subsidiary of the sample organisations. The use of a multi-respondent approach helps to address the well-documented evidence of low reliability of single-rater responses (Gerhart, Wright, McMahan & Snell, 2000; Guest & Conway, 2011). Moreover, the use of multi-respondents should help to ensure that any common method variance bias – especially in relation to perceived subsidiary performance - will be reduced (see Wall, Michie, Patterson, Wood, Sheehan, Clegg & West, 2004). In order to explore the relationships outlined above, it was important to generate a sample size that could be statistically and econometrically interrogated. The method used to collect such data was a large-scale telephone survey conducted by a professional survey company.The interviews ranged in duration from 30-50 minutes. All of the data were collected between 2009 and 2010. The method required translating the survey instrument into multiple languages (specifically, Czech, Hungarian and Polish). The translation effort was guided by two key objectives: achieving construct equivalence and word equivalence. Construct equivalence refers to preserving the exact meaning of the question asked, and at the same time, adapting the questions to the particular language and culture (Cascio, 2012; Mullen, 1995). 11 The following procedures were used to try to achieve these objectives: (1) initial translation of the survey from UK English to the local language by a bilingual and native speaker of the local language; (2) reverse translation of the survey from the local language to UK English; (3) comparisons of the originals with the double-reverse-translated English by subject-expert native speakers; (4) resolution of discrepancies by the translators and development of revised instruments; and (5) extensive piloting of the telephone survey conducted by native speakers with HR Specialists/Manager and line managers - in the presence of the principal researcher - which resulted in further revisions of the instruments and the ordering of several of the questions. Population & Survey Sample Characteristics The population was provided by the Dun and Bradstreet’s (D&B) Global Reference Solution (GRS) database.The GRS database is the most comprehensive and detailed source for information on complex organisations, specifically MNCs (see Henriques, 2009 for detail). The sample was drawn from the GRS database using the following criteria: 1. the ‘global ultimate parent company’ was in the UK (the UK ownership criteria was used to eliminate potential ‘country of origin’ effects); 2. employed at least 200 people overall (this criteria was used so that the data could be compared with other such surveys – e.g., Cranet – which also uses this size criteria); 3. and it had a subsidiary in at least one of the three study countries (i.e., Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland). Three-hundred and seventy-eight organisations met the selection criteria. The analysis presented in this paper is based on data for the organisation’s foreign subsidiaries only. Completed ‘matched’ interviews were achieved in 163 foreign subsidiaries (representing a 12 response rate of 43.1% and 326 completed interviews among these respondents). Sixty-two of the study subsidiaries were based in Poland; 53 in the Czech Republic; 48 in Hungary. A minimum quota of 40 responses per country was set. A two stage Heckman test was used to test for response bias. The results were not statistically significant.2 Measures HR practices. Following a thorough review of the literature and pilot interviews, HR practices were measured using 42 items that divided into eight groups covering: recruitment and selection; training and development, in particular management development; appraisal; compensation and financial flexibility; job design; two-way communication; employment security and the internal labour market; and quality/involvement. The emphasis was placed on what the literature would identify as ‘high performance’ or ‘high commitment’ as opposed to traditional practices (Guest & Conway, 2011). Data on all 42 HR practices were collected only from the HR managers. In order to measure the HR system as a whole, and consistent with common practice, a mean score across the practices is used as the indicator of the presence of HR (see Becker & Huselid, 1998; Guest & Conway, 2011). As the number of items in each of the eight areas of HR differed, the scores were standardised to ensure that equal weighting was given to each. 2 The full database contains a matched sample whereby the UK HR Director and two HR managers/specialists and two line managers in the organisation’s UK and foreign subsidiaries completed interviews (5 respondents per organisation). This paper only utilises the foreign subsidiary data. The contact with the headquarters in the UK greatly facilitated access to the overseas subsidiaries. 13 Implementation. Refers to the empirically observable behaviours constituting the enactment of the transferred practice (Kostova & Roth, 2002). It reflects the adoption of formal rules and/or practices. For each of the eight HR practices listed above, respondents were provided a five-point scale which asked whether the practice was implemented ‘not at all, in practice’ (1) to ‘always used, in practice’ (5). Factor analysis confirmed one clear factor (alpha 0.82 for HR Specialists/Managers and 0.78 for line managers). For the subsequent analysis, the mean scores on these scales are used. Internalisation. Refers to the subsidiary’s overall commitment to the HR practice. Internalisation involves attaching symbolic meaning and value to the practice in question. Drawing upon Kostova & Roth’s definition of internalisation (2002: 217), for each of the eight HR practices listed above, respondents were asked whether they ‘viewed the practice as valuable for the subsidiary and were committed to the practice’ with responses ranging from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘very much so’ (5). Factor analysis confirmed one factor (alpha 0.79 for HR Specialists/Managers and 0.75 for line managers). For the subsequent analysis, the mean scores on these scales are used. Control measures. A number of standard control variables which have been found to be significant in previous analysis of the HR-performance relationship were included.These control variables included size (the number of employees in the subsidiary); sector (1 = services, 0 = manufacturing); age; capital intensity (total assets/total employment, past 3 years [obtained from D&B database or corporate HQ]); sales growth (average change in annual sales turnover, past 3 years [obtained from D&B database or corporate HQ]); the proportion employees who were trade union members (i.e., 1 = 0%; 2 = 1-25%; 3 = 26-50%; 14 4= 51-75%; and 5 = 76 – 100%); and country where the subsidiary is located (0 = Poland; 1 = Hungary; 2 = Czech Republic). Poland is the omitted category in the estimations. Perceived subsidiary performance. (Dependent Variable): To derive a quantifiable measure of perceived subsidiary performance for each subsidiary, an index modified from Delaney & Huselid (1996) was utilised. The index used includes eight items: 1. the firm’s quality of products/services; 2. success at developing new products/services (innovation); 3 and 4. the efficiency of factors of production ((a) labour and (b) capital); 5 and 6. customer/client (a) satisfaction and (b) retention; 7. relative financial performance; and 8. whether overall subsidiary performance has exceeded forecasts/expectations. Respondents were asked to rate their organisation’s outcomes over the past 3 years compared with their main competitors in their sector. Factor analysis confirmed one factor (alpha 0.83 for HR Specialists/Managers and 0.80 for line managers). For the subsequent analysis, the mean scores on these scales are used. Data Analysis Aggregation of individual ratings in the estimations, where applicable, is justified using standard thresholds for the interclass correlation analysis (ICC) 1 and (ICC) 2 measures of greater than 0.20 (Judge & Bono, 2000) and 0.70 respectively (George & Bettenhausen, 1990).The data were subjected to a series of hierarchical regression analyses to the hypotheses. Aiken & West’s (1991) recommendations for testing interaction were followed. Specifically, the interaction term was created by multiplying the mean-centred values of the 15 two variables (implementation*internalisation). Mean-centering reduces multi-collinearity between the interaction term and its components (Aiken & West, 1991). The final hypothesis concerns the relationship between the typologies of adoption (whether ‘active’; ‘assent’; ‘ceremonial’; or ‘minimal’) and their association to perceived subsidiary performance, controlling for the number of HR practices in place. To examine these relations, the subsidiaries were classified by standardising the implementation and internalisation measures and then K-means clustering was used to determine group identification (see also, Kostova & Roth, 2002). Based on these clusters, each subsidiary was assigned an adoption typology. The omitted category in the estimations is ‘minimal’ adoption. RESULTS Insert Table 1 around here The means, standard deviations and inter-correlations are given in Table 1. The intercorrelations are positive and significant for the key study variables – the relationship between perceived subsidiary performance and the number of HR practices present (p<0.05); implementation (p<0.001); and internalisation (p<0.10) of HR practices. There are positive and significant relationships found between perceived subsidiary performance and half of the control variables: firm size (positive at p<0.10); capital intensity (positive at p<0.05); sales growth (positive at p<0.05); and Hungary (negative at p<0.05), reflecting, at least in part, the country’s deep recession and related IMF bail-out during the survey period. 16 Insert Table 2 around here Estimation of hypothesis 1 (Model 2, Table 2) finds a positive and significant relationship between a greater number of HR practices – the presence of practices - and positive subsidiary performance is found (at the p<0.05 level). Thus, hypothesis 1 is not rejected. Hypotheses 2(a) and 2(b) propose that the implementation and internalisation of HR practices will be more strongly associated with perceived performance than the presence of the practices. Considering the effects indicated by changes in R-square, greater implementation and internalisation of HR practices, is indeed more strongly associated with perceived subsidiary performance than the presence of HR practices only (Model 2 compared to Model 3, Table 2). The results for implementation (hypothesis 2(a)) are very significant (p<0.001); while the results for internalisation (hypothesis 2(b)) are significant but only at the p<0.10 level. The interaction of higher implementation and internalisation is found to be very significantly associated with performance (p<0.001) (Model 4, Table 2). Changes in the Rsquare and F-statistics between the non-interacted and interacted models are also significant. These findings, therefore, provide strong support for hypothesis 2(c) that these two HR transfer processes, when taken together, have an important influence on perceived subsidiary performance and have a stronger association with perceived performance outcomes than the presence of HR practices, or the presence of one transfer process only. Insert Table 3 around here 17 The final hypotheses examines whether there is an association between HR adoption typologies and perceived subsidiary performance. In these estimations, the number of HR practices is treated as a control variable, so that the effects of the typologies can be isolated. ‘Active’ adoption is positively and very significantly associated with perceived subsidiary performance (p<0.001) (hypothesis 3(a)). The association between a typology of in ‘assent’ is positive and significant (at the p<0.05 level). In subsidiaries where transfer was ‘ceremonial’, the relationship with perceived subsidiary performance was positive but not significant. The results presented in Table 3 use ‘minimal’ HR as the omitted category to provide insight into how higher implementation and internalisation are associated with perceived performance. However, separate regression results were run entering ‘minimal’ into the regression and the results were consistently negative but not significant.3 This supports hypothesis 3(b) which proposed that the association with perceived performance in subsidiaries where the transfer of HR practices was minimal was unlikely to be statistically significant and may be negative. DISCUSSION Set within the framework of institutional theory, this paper brought together two strands of HR discourse: the HR-performance and HR-transfer literatures. It also contributes to each of these literatures individually. While the HR-performance relationship has been tested in many national contexts, there is little evidence of whether the relationship is found in organisations’ subsidiaries, specifically the overseas subsidiaries of MNCs. Thus, the context of this study – a focus on foreign subsidiaries - has considerable value. A limitation of the HR-performance literature is a lack of understanding of how the relationship operates, in practice. Researchers have been filling this gap by focussing on how HR processes – e.g., 3 These estimates are available from the author upon request. 18 the effectiveness of HR systems (Guest & Conway, 2011); the ‘strength’ of the HR systems (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004); line manager’s role in the delivery of HR (Björkman, Ehrnrooth, Smale & John, 2011; Maxwell & Watson, 2007) – mediate the HR-performance relationship. Guest & Conway (2011) show that the process of delivery – that is whether HR is effectively delivered – has a stronger impact on performance than the presence of HR practices alone. In contrast to the HR-performance literature, the HR transfer and practice adoption literature by the nature of its very remit, examines HR processes – the extent to which intended HR practices are implemented and internalised in foreign subsidiaries. This paper drew upon the HR processes inherent in this literature and applied it to an investigation of how implementation, internalisation, and their associated adoption typologies may affect any HRperformance relationship found. The mean number of HR practices in the sample subsidiaries was 26.4; and 15.5% of subsidiaries reported that 90% or more of all possible practices examined (42) were present; whereas only 8.3% had less than 10% of the practices present. These findings suggest that transfer of HR practices to this sample of foreign subsidiaries was high. This is consistent with competitive isomorphism and is likely to reflect, at least from the perspective of corporate HQs, the transfer of ‘best practice’ HR into their foreign subsidiaries. The positive association found between a greater presence of HR practices and perceived subsidiary performance suggests that there are indeed efficiencies associated with the transfer of ‘best practice’ (hypothesis 1). Low implementation and internalisation suggests that while a practice may be present, it may have little impact in practice, and thus have a minimal association with performance. The results presented in Table 2 clearly illustrate the risks in considering the presence of HR 19 practices without taking into account the process of delivery – whether the practice was implemented and internalised. The results for the relationship between implementation and perceived subsidiary are particularly significant, which is consistent with Björkman & Lervik’s (2007) theoretical assertion that implementation is the ‘first’ stage of transfer – a necessary but not sufficient condition – for subsequent and more institutionally embedded – stages of transfer, including internalisation (and integration). While the relationship between internalisation and perceived subsidiary performance was only significant at the p<0.10 level (lower than the p<0.05 level for the number of practices and perceived performance), when implementation and interaction were interacted, the significance level of the interacted coefficient was very high (p < 0.001) and the overall explanatory power of the model increased significantly. This suggests that there are very positive synergies for perceived performance associated with transferred HR practices that are implemented and internalised within foreign subsidiaries. There is, therefore, evidence to support hypotheses 2(a); (b); and (c). Developing the framework further, adoption transfer typologies were then examined. The percentage of subsidiaries in each of the typologies was as follows: ‘active’ (23.2%); ‘minimal’ (12.2%); ‘assent’ (30.2%); ‘ceremonial’ (34.4%). The finding that in 76.8% of subsidiaries, the transfer of HR practices was not as HQ is likely to have intended (i.e., the transfer was not ‘active’), does question the extent of realised competitive isomorphism associated with transfer. Does this matter for perceived performance, especially where ceremonial adoption may, given specific institutional contexts, be appropriate and may even reflect a tacit ‘understanding’ from corporate HQs? 20 The results suggest that the type of HR transfer has significant implications for perceived subsidiary performance (hypotheses 3(a) and 3(b)). Positive and significant relationships were found between perceived subsidiary performance and transfer that was ‘active’ (p<0.001) and in ‘assent’ (p<0.05). No significance was found where transfer was‘ceremonial’ and a negative was found where transfer was‘minimal’. The estimations also show a decline in the significance of the presence of HR practices for perceived performance when treated as a control variable and the process of delivery – categorised by HR adoption typology – is estimated (Table 3). Thus, while the presence of HR practices make a necessary contribution to perceived performance, it certainly does not appear to be a sufficient contributor to the relationship. This study suggests that the sufficiency of HR to perceived performance requires implementation and internalisation of HR practices. In other words, the complex processes associated with the delivery of HR in foreign subsidiaries is an essential link in the HR-performance relationship. CONCLUSION These findings resonate with Truss’ (2001) study of the dynamics of the HRMperformance relationship in Hewlett-Packard which highlighted the importance of context and the role of agency. In terms of the time that it can take for organisational initiatives to become embedded, the significant moderating role of culture, structure, administrative heritage and the role of each individual manager as an agent, who can choose to focus his or her attention in varying ways, was emphasised. Truss concluded her analysis by emphasising: “Problems of implementation and interpretation occur alongside people’s sometime unpredictable responses and actions” (2001: 1146). 21 This study also contributes to the growing literature which acknowledges the pivotal role of understanding processes associated with the delivery of HR and how processes are likely to interact with, and mediate, the HR-performance relationship. While it is found that a greater number of HR practices have a positive association with perceived performance - the extent to which practices are implemented and internalised by employees in subsidiaries - has an even greater impact on subsidiary performance than just the presence of HR practices. Research Implications and Limitations While this paper makes important contributions to both the HR-performance and practice transfer literatures, it is, of course not without its limitations which provide rich material for future research. While analysis of quantitative data provides important insights into patterns found between the variables examined, it cannot provide insight into the complex institutionally specific factors that have generated the relationships found. Case study work will be used to explore these processes, especially issues pertaining to the role of national context, the influence of corporate HQs, and the role of the subsidiary within the overall MNC’s network of subsidiaries. The potential significant role of divergence in perceptions about transfer between HR Specialists/Managers and line managers and the implications of divergence between these key agents was not examined - rather their perceptions were aggregated and averaged to temper the potential for common methods variance bias. This critical issue will be examined in future analysis. 22 While access to MNCs and especially access to multiple responses from within these organisations is increasingly challenging for researchers, it will be important to examine how processes associated with the delivery of HR and any associated implications for subsidiary performance applies to other regions of the world. This will be especially important where cultural and institutional divergence between corporate HQs and foreign subsidiaries is larger than that examined here – which was set within the EU. Finally, the analysis has important implications for HR practitioners – where attempted HR transfer is only minimally or ceremonially adopted, the efficiencies associated with HR transfer are negligible, and in the case of the former, may even have negative implications for performance. It is therefore important that when HR practice transfer is attempted – and practitioners, of course, need to be very cognisant of the potential of perceived coerciveness and cultural inappropriateness, and in such cases it is likely that such transfer will not be attempted - but where transfer proceeds, the findings from this study suggest that in order for transfer to have a positive influence on performance, it must occur in tandem with policies to ensure higher levels of implementation and internalisation. 23 REFERENCES Aiken, L. & West, S. 1991. Multiple Regressions: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park: CA: Sage. Becker, B. & Huselid, M. 1998. Higher Performance Work Systems and Firm Performance: a synthesis of research and managerial implication. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management, 16: 53-101. Björkman, I., Ehrnrooth, M., Smale, A. & John, S. 2011. The determinants of line management internalisation of HRM practices in MNC subsidiaries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(8): 1654-1671. Björkman, I. & Lervik, J. 2007.Transferring HR Practices within multinational corporations. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(4): 320-335. Boselie, P., Dietz, G. & Boon, C. 2005. Commonalities and contradictions in the HRM and performance research. Human Resource Management Journal, 15: 67-94. Bowen, D. & Ostroff, C. 2004. Understanding the HRM-Performance Linkages: the role of the ‘strength’ of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29: 203-221. 24 Cascio, W. (2012, forthcoming). Methodological issues in international HR Management Research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Special Issue: Global HRM and Economic Change. Collings, D. & Dick, P. 2011. The relationship between ceremonial adoption of popular management practices and the motivation for practice adoption and diffusion in an American MNC. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(18): 3849-3866. Combs, J., Ketchen, D., Hall, A. & Liu, Y. 2006. Do high performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effect on organisational performance. Personnel Psychology, 59: 501-528. Delaney, J. & Huselid, M. 1996. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Perceptions of Organisational Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4): 949-969. DiMaggio, P. & Powell, W. 1983. The Iron Age Revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2): 147-160. Edwards, T., Colling, T. & Ferner, A. 2007. Conceptual approaches to the transfer of employment practices in multinational companies: an integrated approach. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(3): 201-217. 25 Farndale, E. & Paauwe, J. 2007.Uncovering competitive and institutional drivers of HRM practices in multinational corporations. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(4): 355-375. Ferner, A., Almond, P., Clark, I., Colling, T., Edwards, T., Holden, L. & Muller-Carmen, M. 2004. The Dynamics of Central Control and Subsidiary Autonomy in the Management of Human Resources: Case Study Evidence from US MNCs in the UK. Organisational Studies, 25(3): 363-391. Foley, S., Ngo, H-y., & Loi, R. 2010.The adoption of high performance work systems in foreign subsidiaries. Journal of World Business, 47(1): 106-113. George, J.M. & Bettenhausen, J. 1990. Understanding procsocial behaviour, sales performance, and turnover: a group-level analysis in a service context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75: 698–709. Gerhart, B., Wright, P., McMahan, G. & Snell, S. 2000. Measurement error in research on human resources and firm performance: how much error is there and how does it influence size estimates? Personnel Psychology, 53: 803-834, Guest, D. 2011. Human resource management and performance: still searching for some answers. Human Resource Management Journal, 21(1): 3-13. 26 Guest, D. & Conway, N. 2011.The impact of HR practices, HR effectiveness and a 'strong HR system' on organisational outcomes: a stakeholder perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(8): 1686-1702. Henriques, M. 2009. UK Database, Global Linkage and Global Data Collection. Internal Dun and Bradstreet (D&B) report on the representativeness and reliability of the Global Reference Solutions (GRS) database. Marlow, Buckinghamshire: D&B UK Head Office. Judge, T. & Bono, J. 2000.Five-factor model of personality and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5): 751-765. Kim, Y. & Mauborgne, R. 1993. Procedural justice, attitudes, and subsidiary top management compliance with multinationals’ corporate strategic decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3): 502-526. Konrad, A.M., Waryszak, R. & Hartmann, L. 1997. What do managers like to do? Comparing women and men in Australia and the US. Australian Journal of Management, 22(1): 71-97. Kostova, T. 1999. Transnational transfer of strategic organisational practices: a contextual perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24: 308-324. Kostova, T. & Zaheer, S. 1999. Organisational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: the case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24: 64-81. 27 Kostova, T. & Roth, K. 2002.Adoption of an organisational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: Institutional and Relational Effects. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1): 215-233. Maxwell, G. & Watson, S. 2006. Perspectives on line managers in human resource management: Hilton International’s UK hotels. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(6): 1152-1170. McDonnell, A., Lamare, R., Gunnigle, P. & Lavelle, J. 2010. Developing tomorrow’s leaders – evidence of global talent management in multinational enterprises. Journal of World Business, 45: 150-160. Morley, M.J., Heraty, N. & Michailova, S. 2009. Managing Human resources in Central and Eastern Europe. New York, NY: Routledge. Mullen, M. 1995. Diagnosing measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Journal of International Business Studies. 26: 573-597. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2009), Statistics Portal, http://www.oecd.org/statsportal/0,3352,en_2825_293564_1_1_1_1_1,00.html (accessed December 2011). 28 Purcell, J. & Hutchinson, S. 2007. Front-line managers as agents in the HRM-performance causal chain: theory, analysis and evidence. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(1): 3-20. Purcell, J. & Kinnie, N. 2007. HRM and Business Performance. In P. Boxall, J. Purcell, J. & P. Wright (Eds). The Oxford Handbook of Human Resource Management: 533-551. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Regner, P. 2003. Strategy creation in the periphery: inductive versus deductive strategy making. Journal of Management Studies, 41(1): 57-82. Sanders, K. & Frenkel, S. 2011. Introduction: HR-line management relations: characteristics and effects. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(8): 1611-1617. Szulanski, G. 1996. Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal (winter special issue): 27-43. Truss, C. 2001. Complexities and Controversies in Linking HRM with Organisational Outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 38(8): 1121–1149. Wailes, N., Ramia, G. & Lansbury, R. 2003.Interests, Institutions and Industrial Relations.British Journal of Industrial Relations, 41(4): 611-627. 29 Wall, T., Michie, J., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Sheehan, M., Clegg, C. & West, M. 2004. On the Validity of Subjective Measures of Company Performance. Personnel Psychology, 57(1): 95–118. 30 FIGURE 1 Adoption Typologiesa Level of implementation of HR Practices Level of internalisationof HR Practices a High Low Low Ceremonial Minimal High Active Assent :Based on Kostova and Roth (2002) . 31 TABLE 1 Means, standard deviations and correlations for study variablesa Mean S.D. V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V1 Ln (Age) 2.103 0.66 V2 Ln (Size) 2.252 0.54 0.073 V3 Services 0.314 0.467 0.078 0.065 V4 Ln (Capital Intensity) 2.586 1.006 0.132 0.227** -0.023 V5 Ln (Sales growth) 0.695 0.654 0.066 0.218*** -0.055 0.152* V6 Trade Union Density 1.150 0.257 0.055 0.102 -0.054 0.025 -0.026 V7 Country (Poland V6 V7 V8 V9 V10 omitted) V8 HR practices 0.264 4.133 0.145 0.223** -0.032 0.142 0.140* 0.025 0.089 V9 Implementation 3.266 0.591 0.156 -0.067 -0.024 0.089 0.158* 0.021 0.026 0.215** V10 Internalisation 3.117 0.612 0.137 -0.126 -0.020 0.071 0.143* 0.019 0.012 0.199* 0.588*** V11 Perceived subsidiary 3.185 0.793 0.142 0.181* -0.049 0.218** 0.316** 0.114 -0.213** 0.203** 0.229*** 0.182* Performance a : * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. Based on matched sample of HR manager and a line manager (total possible responses for multiple-respondent variables = 326 (163*2)). Variables 1-5 were obtained from the D&B Global Reference Solution database; N for V6 = 163, based on responses from the HR manager; N for V7-V10 ranges between 302 and 326 depending on missing values. 32 TABLE 2 Regression results examining associations between the presence of HR practices, implementation, internalisation and perceived subsidiary performancea Variables Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 (H 1) (H 2a and 2b) (H 2c) Step 1: ControlVariables Ln (Age) 0.106 0.109 0.111 0.114 Ln (Size) 0.152* 0.150* 0.151* 0.153* Services -0.052 -0.051 -0.054 -0.056 Ln (Capital intensity) 0.211** 0.213** 0.216** 0.212** Ln (Sales growth) 0.218** 0.219** 0.220** 0.223** Trade Union Density -0.057 -0.053 -0.055 -0.051 Czech Republic -0.132 -0.130 -0.133 -0.135 Hungary -0.203* -0.205* -0.207* -0.210* 0.208** 0.202** 0.192* Implementation 0.387*** 0.378*** Internalisation 0.146* 0.151* Country (reference category: Poland) Step 2: Number of HR Practices Step 3: Step 4: Interaction terms Implementation * Internalisation 2 Model R 2 Adjusted R Model F 2 ∆R N(subsidiaries) a 0.285*** 0.118 0.109 4.116* 0.286 0.235 6.113** 0.406 0.392 11.272*** 0.691 0.656 16.271*** 162 0.126** 160 0.157*** 158 0.264*** 158 : * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. 33 TABLE 3 Regression results examining associations between HR transfer typologies and perceived subsidiary performance Variables Model 1 Model 2 (H 3) Step 1: ControlVariables Ln (Age) 0.113 0.111 Ln (Size) 0.155* 0.152* Services -0.054 -0.050 Ln (Capital intensity) 0.215** 0.217** Ln (Sales growth) 0.222** 0.223** Trade Union Density -0.058 -0.058 Czech Republic -0.139 -0.138 Hungary -0.213** -0.214** Number of HR Practices 0.220** 0.189* Country (reference category: Poland) Step 2: Adoption Typologies Active 0.427*** Assent 0.226** Ceremonial 0.109 2 Model R 2 Adjusted R Model F 2 ∆R N(subsidiaries) a 0.286 0.235 0.602 0.585 6.113** 160 15.031*** 0.350*** 158 : * significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. 34

![[DOCX 51.43KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007172908_1-9fbe7e9e1240b01879b0c095d6b49d99-300x300.png)