Comorbid insomnia

advertisement

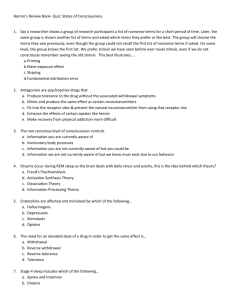

Insomnia and Primary Care Ruth Benca, MD PhD Wisconsin Sleep Insomnia defined Diagnosis requires one or more of the following: difficulty initiating sleep difficulty maintaining sleep waking up too early, or sleep that is chronically nonrestorative or poor in quality Sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep. Insomnia is not sleep deprivation, but the two may coexist. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed.: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005. Insomnia must be associated with daytime impairment At least one daytime impairment related to the nighttime sleep difficulty must be present: Fatigue/malaise Attention, concentration, or memory impairment Social/vocational dysfunction or poor school performance Mood disturbance/irritability Daytime sleepiness Motivation/energy/initiative reduction Proneness for errors/accident at work or while driving Tension headaches, and/or GI symptoms in response to sleep loss Concerns or worries about sleep American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed.: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005. Comorbid insomnia Impacts quality of life and worsens clinical outcomes1,2 Predisposes patients to recurrence3 May continue despite treatment of the primary condition4 “Comorbid insomnia”more appropriate than “secondary insomnia,” because limited understanding of mechanistic pathways in chronic insomnia precludes drawing firm conclusions about the nature of these associations or direction of causality. Considering insomnia to be “secondary” may also result in undertreatment.5 1 Roth T, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep. 1999;22:S354-S358. 2 Katz DA, McHorney CA. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:229-235. PP, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:105-114. 4 Ohayon MM, Roth T. Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:9-15. 5 National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults, June 13-15, 2005. National Institutes of Health. Sleep. 2005 Sep 1;28(9):1049-1057. 3 Chang Epidemiology of insomnia General population: 10-15% Clinical Practice: > 50% The prevalence and treatment of primary insomnia have been the most studied (less than 20% of cases)1,2 Comorbid insomnia accounts for >80% of cases 1 Simon 2 Hajak GE,Vonkorff M. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1417-1423. G. Sleep. 2000; 23:S54-S63. At-risk populations for insomnia Female sex Increasing age Comorbid medical illness (especially respiratory, chronic pain, neurological disorders) Comorbid psychiatric illness (especially depression, depressive symptoms) Lower socioeconomic status Race (African American > White) Widowed, divorced Non-traditional work schedules Why insomnia is a disorder, not just a symptom • Relative consistency of insomnia symptoms and consequences across comorbid disorders • Course of insomnia does not consistently covary with the comorbid disorder • Insomnia responds to different types of treatment than the comorbid disorder • Insomnia responds to the same types of treatment across different comorbid disorders • Insomnia poses common risk for development of and poor outcome in different disorders Harvey, Clin Psychol Rev, 2001; Lichstein et al., Treating Sleep Disorders, 2004 Increased prevalence of medical disorders in those with insomnia N=401 N=137 % p<.001 p<.001 p<.001 p<.001 p<.01 p<.05 p<.01 p<.05 Heart Cancer Disease HTN Neuro- Breath- Urinary Diabetes Chronic logic ing Pain GI p values are for Odds Ratios adjusted for depression, anxiety, and sleep disorder symptoms. From a community-based population of 772 men and women, aged 20 to 98 years old. Taylor DJ., et al. Sleep. 2007;30(2):213-218. Any medical problem Increased prevalence of insomnia in those with medical disorders Survey Of Adults (N=2101) Living In Tucson, Arizona, Prevalence, % Assessed Via Self-administered Questionnaires * * ** * *P ≤ .001, **P ≤ .005 vs. no health problem ASVD, arteriosclerotic vascular disease; OAD, obstructive airway disease. Klink ME et al. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1634-1637. * Insomnia prevalence increases with greater medical comorbidity Percent of Respondents Reporting any Insomnia 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 1 2 or 3 4 Number of Medical Conditions Self-reported questionnaire data from 1506 community-dwelling subjects aged 55 to 84 years Foley D, et al. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497-502. Psychiatric disorder is the most common condition comorbid with insomnia Other DSM-IV Distribution of Insomnia(64%) No DSM-IV diagnosis (24%) Other sleep disorders (5%) Insomnia due to a general medical condition (7%) Substance-induced insomnia (2%) Insomnia related to another mental disorder (10%) Primary insomnia (16%) Adjustment disorder (2%) Psychiatric Disorders (36%) Anxiety disorder (24%) Bipolar disorder (2%) Depressive disorder (8%) N=20,536. European meta-analysis Ohayon MM. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97-111. Relative risk for psychiatric disorders associated with insomnia 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 2 1 1Breslau, 1996. N=1007 2Ford and Kamerow, 1989. N=811 1 2 1 1Breslau N, et al. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411-418. 2Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479-1484. Timing of insomnia related to onset of psychiatric illness N=14,915 Ohayon MM , Roth T. J Psychosom Res. 2003;37:9-15. Insomnia is a risk factor for later-life depression Cumulative Incidence (%) 40 Insomnia Yes No 35 30 25 Total 137 887 Cases 23 76 P=.0005 20 15 10 5 0 0 Insomnia* Yes No 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 99 616 27 382 9 216 Follow-up Time (Years) 137 887 135 877 133 859 127 838 * Number of men included at each time point. Chang P et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:105-114. 117 799 106 740 Objective sleep abnormalities are seen in psychiatric patients TST SE SL SWS REM L Mood Alcoholism Anxiety Disorders Schizophrenia Insomnia Comparison of sleep EEG in groups of patients with psychiatric disorders or insomnia to age-matched normal controls. Benca RM et al. Arch Gen Psych. 1992;49:651-668 Bidirectional relationship between psychiatric disorders and insomnia PSYCHIATRIC ISSUES Anxiety Depression Insomnogenic drugs Substance abuse Altered ACTH and cortisol Concerns or worries about sleep ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone TST, total sleep time SOL, sleep onset latency SWS, slow wave sleep INSOMNIA Decreased TST Increased SOL Impaired sleep efficiency Decreased SWS Sleep and menopause Peri- and postmenopausal women have more sleep complaints1 41% of early perimenopausal women report sleep difficulties2 Frequent awakenings suggest insomnia is secondary to vasomotor symptoms3 However, waking episodes may occur in absence of hot flashes4 1Young T, et al. Sleep. 2003;26:667-672. al. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473. 3Woodward S, Freedman RR. Sleep.1994;17:497-501. 4Polo-Kantola P, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:219-224. 2Gold E, et Complaints of sleep problems with age 50 40 30 20 10 0 10-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 Age Group, y 60-69 “Trouble With Sleeping” Assessed in a comprehensive survey of 1645 individuals in Alachua County, Florida Karacan I et al. Soc Sci Med. 1976;10:239-244. 70+ Prevalence of insomnia by age group % Age Group, years Large-scale community survey of non-institutionalized American adults, aged 18 to 79 years Mellenger GD, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:225-232. Patients with pain report poor sleep 287 subjects reporting to pain clinic Mean age, 46.7 years; half with back pain 89% reported at least 1 problem with sleep Significant correlations between sleep and Physical disability Psychosocial disability Depression Pain McCracken LM, Iverson GL. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7:75-79. Insomnia comorbid with pain Control Any pain* % N=18,980; p<.001. Based on survey data. *Pain categories included limb pain, backaches, joint pain, GI pain, and headaches. Ohayon MM. J Psychiatr Res. 2005 Mar;39(2):151-159. Bidirectional relationship between pain and insomnia PAIN DIS, difficulty initiating sleep DMS, difficulty maintaining sleep INSOMNIA Poor sleep quality Nonrestorative sleep DIS DMS Sleep and cancer • 30% to 75% of newly diagnosed or recently treated cancer patients complain of insomnia (double that of the general population) • Sleep complaints in cancer patients consist of • difficulty falling asleep • difficulty staying asleep • frequent and prolonged nighttime awakenings • Complaints occur before, during and after treatment Fiorentino L, Ancoli-Israel, S. Sleep dysfunction in patients with cancer. Curr Treat Opt Neurol. 2007;9:337–346. Risk factors for insomnia in cancer patients Risk Factor Examples Disease factors Tumors that increase steroid production, symptoms of tumor invasion (pain, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, pruritis) Treatment factors Frequent monitoring, corticosteroid treatment, hormonal fluctuations, fatigue Medications Narcotics, chemotherapy, neuroleptics, sympathomimetics, sedative/hypnotics, steroids, caffeine/nicotine, antidepressants, diet supplements Environmental factors Disturbing light and noise, temperature extremes Psychosocial disturbances Depression, anxiety, delirium, stress Physical disorders Headaches, seizures, snoring/sleep apnea O'Donnell JF. Clin Cornerstone. 2004;6(Suppl 1D):S6-S14. Bidirectional relationship between insomnia and cancer CANCER-RELATED ISSUES Pain Psychiatric comorbidities Fatigue Opioids (daytime sedation, SDB) Insomnogenic drugs Napping Preexisting sleep disorders INSOMNIA SDB, sleep-disordered breathing Fiorentino L, Ancoli-Israel, S. Sleep dysfunction in patients with cancer. Curr Treat Opt Neurol. 2007;9:337–346. Insomnia and OSA or CSA Studies have shown that 39% to 55% of patients with OSA have comorbid insomnia. Associated factors include: female gender psychiatric diagnoses restless leg symptoms chronic pain lower AHI, lower DI OSA patients with comorbid insomnia have More severe sleep apnea Increased depression, anxiety and stress AHI, apnea hypopnea index. CSA, central sleep apnea. DI, desaturation index. OSA, obstructive sleep apnea. Krell SB, KapurVK. Sleep Breathing. 2005;9:104-10. Smith S, et al. Sleep Med. 2004;5:449-456. Insomnia and OSA or CSA < 1% of 1,000 patients with OSA surveyed had been diagnosed with insomnia Mood problems were not formally addressed In a small study of patients with CSA (n=14): 36% had sleep onset insomnia 79% had maintenance insomnia This rate was significantly higher than in patients with OSA (P =.016) MorganthalerTI,et al. Sleep. 2006;29:1203-1209. Smith S, et al. Sleep Med. 2004;5:449-456. Insomnia and COPD >50% of patients with COPD have insomnia 25% complain of excessive daytime sleepiness Medications for COPD contribute to insomnia Inhaled or PO; anticholinergics, corticosteroids, beta-2-agonists, theophylline; bupropion used for smoking cessation Sleep deprivation may attenuate ventilatory response to hypercapnia in patients with COPD, leading to further desaturation and sleep disruption George CFP. Sleep. 2000;23:S31-S35. White DP, et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:984-986. Insomnia and COPD Insomnia linked with comorbidities of COPD Eg, depression, smoking, orthopnea, and nocturnal hypoxemia Suggests multiple factors in pathogenesis of insomnia in COPD Insomnia can impair pulmonary function Spirometric decline is observed after one night of sleep deprivation Despite importance of treating the underlying COPD, this may not lead to improvement of insomnia in clinical practice Cormick W, et al. Thorax. 1986;41:846-854. Kutty K. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:104-112. Maggia S, et al. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1998;46:161-168. Phillips BA, et al. Chest. 1987;91:29-32. Wetter DW, et al. Prev Med. 1994;23:328-334. Insomnia may be a predictor of hypertension HTN Incidence (%) 95% CI: 1.42-2.70 n=192 95% CI: 1.45-2.45 n=286 n=4602 n=4157 N=9237 male Japanese workers assessed for difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep and followed up for 4 years or until the development of HTN (initiation of anti-HTN therapy or a SBP of ≥140 mmHg or a DBP of ≥140 mmHg). Results adjusted for BMI, tobacco and alcohol use and job stress. Suka M, et al. J Occup Health. 2003;45:344-350. Short sleep duration and hypertension: NHANES I and the Sleep Heart Health Study ≤6h ≤5h 6-7h 6h 7-8h 7-8h (1.0; referent) 8-9h ≥9h Hazard Ratios. N=4180. Subjects 32-59y. Sleep duration and increased risk of HTN, adjusted for multiple confounders including physical activity, alcohol/salt consumption, smoking, age, overweight/obesity, and diabetes. Gangwisch et al. Hypertension. 2006;47:833-839. (1.0; referent) ≥9h Odds Ratios. N=5910. Subjects 40- 100y. Sleep duration and increased risk of HTN adjusted for age, sex, race, apneahypopnea index and BMI. Gottlieb DJ, et al. Sleep. 2006;29(8):1009-1014. Relationships between sleep disorders* and obesity Increased BMI1 Increased insulin resistance2 Reduced leptins3 Diabetes4 Impaired glucose tolerance4 Obesity Increased TC, HDL and triglycerides1 Factors associated with reduced sleep time* may contribute to obesity *Insomnia or sleep deprivation. 1 Bjorvatn B, et al. J Sleep Res. 2007;16(1):66-76. 2 Flint J, et al. J Pediatr. 2007;150(4):364-369. 3 Chaput JP, et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(1):253-261. 4 Gottlieb et al. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:863-868. Management of insomnia Treat any underlying cause(s)/comorbid conditions Promote good sleep habits (improve sleep hygiene) Consider cognitive behavior therapy Consider medications to improve sleep Kupfer DJ and Reynolds CF III. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:341-346. Practicing good sleep hygiene Avoid: “watching the clock” use of stimulants, eg, caffeine, nicotine, particularly near bedtime1,3 heavy meals or drinking alcohol within 3 hours of bed1 exposure to bright light during the night 1,3 Enhance sleep environment: dark, quiet, cool temperature1,3 Increase exposure to bright light during the day 2 Practice relaxing routine 1-3 Reduce time in bed; regular sleep/wake cycle 1-3 Time regular exercise for the morning and/or afternoon 1,3 1 NHLBI Working Group on Insomnia. 1998. NIH Publication. 98-4088. DJ, Reynolds CF. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:341-346. 3 Lippmann S et al. South Med J. 2001;94:866-873. 2 Kupfer Behavioral techniques Technique Aim Stimulus control therapy Imprint bed and bedroom as sleep stimulus Sleep restriction Restrict actual time spent in bed to enhance sleep depth & consolidation Cognitive therapy Address dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep Relaxation training Decrease arousal and anxiety Circadian rhythm entrainment Reinforce or reset biological rhythm using light and/or chronotherapy Cognitive behavior therapy Combination of behavioral and cognitive approaches listed above Drugs indicated for insomnia Generic Brand T1/2 (Hours) Dose (mg) Drug Class Flurazepam Dalmane 48-120 15-30 BZD Temazepam Restoril 8-20 15-30 BZD Triazolam Halcion 2-6 0.125-0.25 BZD Estazolam Prosom 8-24 1-2 BZD Quazepam Doral 48-120 7.5-15 BZD Zolpidem Ambien 1.5-2.4 5-10 non-BZD Zaleplon Sonata 1 5-20 non-BZD Eszopiclone† Lunesta 5-7 1-3 non-BZD Ambien CR 1.5-2.4* 6.25-12.5 non-BZD Rozerem 1.5-5 8 MT agonist Zolpidem Ex Rel† Ramelteon† * Modified formulation. †No short-term use limitation. Antidepressants for Insomnia: Indications Patients with psychoactive substance use disorder history Patients with insomnia related to depression, anxiety Treatment failures with BzRA Suspected sleep apnea Fibromyalgia Primary insomnia (second-line agents) Not FDA-approved for use as hypnotics Antidepressant drug effects on sleep Tricyclic Sleep continuity Slow wave sleep REM sleep Other To To To PLMs Apnea To To To Eye movements in NREM PLM apnea Trazodone, Nefazodone To To Trazodone more sedating Bupropion To No increase in PLM Mirtazapine Low doses sedating SSRI Improve comorbid conditions Treat insomnia When to refer an insomnia patient to Sleep Clinic: Medical and psychiatric comorbidities have been assessed and are adequately treated Patient has been instructed in sleep hygiene Patient has failed trials of behavioral and/or pharmacological therapy Other common sleep disorders treated by sleep specialists: Sleep apnea* Restless legs/periodic limb movement disorder Parasomnias Circadian rhythm disorders Narcolepsy* *Typically require sleep laboratory testing as well as clinical evaluation for diagnosis High density-EEG / TMS studies in health and disease pioneered by Giulio Tononi, MD, PhD High density EEG (256 electrodes) recorded across entire night, TMS in wakefulness and sleep Why high-density EEG in sleep? • • • • • • Can now be done routinely; noninvasive and relatively inexpensive What could be done with standard PSG has largely been done (NIH roadmap discourages it) Sleep apnea PSG likely to migrate to home-monitoring Spatial resolution is comparable to PET; temporal resolution is ideal Sleep is a window on spontaneous brain function, unconfounded by attention, motivation, etc. Broad patient population: sleep disorders, psychiatric disorders, neurological disorders (and connection to long-term epilepsy monitoring) V Spontaneous brain rhythms during sleep reflect brain functioning unconfounded by attention and motivation ra 60 40 20 0 -20 -40 -60 spindle activity ( 20 10 0 -10 -20 25 20 slow wave activity 15 upper threshold absolute spindle amplitude spindle activity slow-wave activity (V2) 10000 Fz Cz P4 8000 6000 Fz 4000 Cz P4 2000 0 0 2 4 6 8 Sleep Slow Wave Activity ishoursHomeostatically Regulated Throughout the Cortex Slow waves originate more frequently in orbitofrontal and centroparietal regions and propagate in an antero-posterior direction Diagnosis: Sleep spindle activity is reduced in schizophrenia Schizophrenics Schizophrenics vs. Depressed 100 80 60 40 20 EEG spindle activity (13-15 Hz) P<.05 Schizophrenics vs. Controls Controls Ferrarelli et al., Am. J. Psychiatry, 2007 Depressed vs. Controls Depressed Treatment: Sleep slow oscillations can be triggered by TMS Massimini et al., submitted • Sleep Clinic and 16 Bed Sleep Laboratory - UWMF clinic - Sleep Laboratory joint venture with Meriter • Open with 12 beds, 5 nights/week • Clinic operates 5 days/week • Staff model - approx 30 FTE • Sleep Equipment of Wisconsin - UWHC/Meriter joint venture Interdisciplinary Clinical Expertise Psychiatry R. Benca, MD, PhD M. Rumble, PhD Pulmonary M. Klink, MD S. Cattapan, MD J. McMahon, MD G. DoPico, MD Mihaela Teodorescu, MD Geriatrics S. Barczi, MD Mihai Teodorescu, MD Pediatrics C. Green, MD Neurology J. Jones, MD Clinical Practice Model: Clinic • Referral-based practice. • Improve access. • Standardized assessments of all patients using validated questionnaires, comprehensive evaluations, outcomes measures. All information on electronic database. • Development of behavioral sleep medicine program. • Outreach to primary care. Clinical Practice Model: Laboratory • Encourage referring providers to request studies with management. • Laboratory studies read the next morning. Timely communication with referring physicians; reports sent and/or available electronically within 24 hours of completion. • Sleep Equipment of Wisconsin on-site to provide immediate availability of treatment. Educational program Directed by Steven Barczi, MD ACGME-accredited fellowship Currently only 1 position; application for up to 3 slots per year pending Plan to coordinate medical school and residency training in sleep Lectures in medical school and residency curricula Clinical electives Translational research opportunity Brand new program • Standardized assessment and outcomes measures • State-of-the-art neurophysiological recording techniques • Every patient a potential research subject