Mentoring Strategies for Faculty Career Development_2015_V3

advertisement

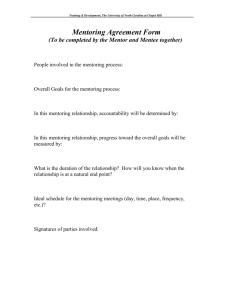

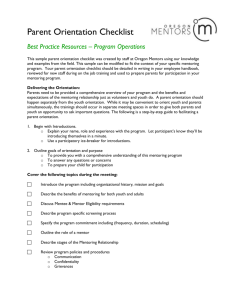

The Delaware-CTR ACCEL Mentoring, Education, & Career Development (MED) Core Retreat “Best Practices in Mentoring” 4/29/15 Mentoring Strategies for Faculty Career Development Helen E. Pearson, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Anatomy and Cell Biology Associate Dean For Faculty Affairs Temple University School of Medicine Conflict of Interest Disclosure I have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose. Outline for this Presentation • Overview of faculty mentoring • 5 Specific Examples of ‘Best Practices’: Departmental program at TUSM for junior faculty 3 School – wide programs at TUSM Targeted program for new members in a AAMC affinity group using mentoring circles What is Mentoring? Berk et al (2005) attempt a broad definition of faculty mentoring as when “..faculty with useful experience, knowledge, skills, and/or wisdom offers advice, information, guidance, support or opportunity to another faculty member …for that individual’s professional development”. Berk RA, Berg J, Mortimer R, Walton-Moss B, Yeo TP. Measuring the effectiveness of faculty mentoring relationships. Acad Med. 2005; 80(1): 66-71. Impact of Faculty Mentoring • • • • Improved job satisfaction Enhanced sense of “fit” Greater faculty productivity Higher retention rates Dandar VM, Corrice AM, Bunton SA, Fox S. Why Mentoring Matters: A Review of Literature on the Impact of Faculty Mentoring in Academic Medicine and Research–based Recommendations for Developing Effective Mentoring Programs. Poster presented at the 2011 First International Conference on Faculty Development in the Health Professions in Toronto, Canada. Evidence-Based Guidelines Developed by Dandar et al (2011) through literature review for establishing or refining a structured faculty mentoring program most likely to result in positive outcomes for faculty and their institutions. • Setting up the program for success • Establish ground rules for participation • Train and incent mentors • Conduct a careful matching process • Hold a mentor-mentee orientation session • Clarify the program’s process steps and outcomes • Incorporate program into existing human capital systems Types of Mentoring • Formal (structured) or informal • One-on-one or one mentor per group of mentees • Traditional ‘senior’ mentor/ ‘junior’ mentee or peermentoring • Single mentor or multiple mentors • Assigned mentor or mentee-selected • Short-term mentoring or sustained • Targeted mentoring (new hires, leadership development, URM) or open for all Multiple Mentors • Most faculty members “wear more than one hat”, and are evaluated on more than one area of expertise. • Responsibilities include research, teaching, clinical/patient care, administration. • One mentor can’t do it all, or have the time to. • Different mentors can help with different aspects of a faculty member’s job. Mentoring URM Faculty Numbers of underrepresented minority faculty lag far behind the increasing numbers of URM undergraduate students. High turnover and attrition of URM faculty undercut the proactive work being done by universities to diversify their faculty. Mentoring URM Faculty Using in-depth interviews and focus group data, a study of URM faculty at research-extensive institutions by Zambrana et al (2015) shows three main themes: • Practices to promote effective mentoring for the academic life course (K-20 and beyond) of URM faculty are critical • Major barriers are linked to undervaluing the research interests and community-engaged scholarly commitments of URM faculty • Connection with mentors who understand struggles of URM faculty at predominantly white institutions can assist with retention and success. Mentoring URM Faculty Zambrana et al (2015) also show that the most frequent mentor-facilitated activities by mentored URM faculty were: • Opportunities for collaboration • Coauthoring papers and books • Invitations to attend conferences • Annual career review Zambrana et al. “Don’t Leave Us Behind”: The Importance of Mentoring for Underrepresented Minority Faculty. Amer. Educational Res. J. , February 2015, 52: 40-72, doi:10.3102/0002831214563063 Barriers to Effective Mentoring Lack of : • Effective mentors • Mentor incentives • Mentor training • Mentee appreciation for value of mentoring Mentor Incentives • Release time from other responsibilities (teaching, clinical, research, administrative) • Financial (stipend) • Mentoring awards (recognition) Mentor Training Few national or institutional programs exist (or at least are publicized!) – One example: Faculty Mentoring Leadership Program at Brigham & Women’s Hospital http://bwhmentoringtoolkit.partners.org/facultymentoring-leadership-program-fmlp-sample-curriculumguide/ Mentor Training BWH FMLP Mentor Training Curriculum: Nine Monthly Interactive Meetings 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Orientation: Creating a Culture of Mentoring & Developing Mentoring Networks Structuring the Mentoring Relationship: Expectations and Boundaries Difficult and/or Complex Mentoring Situations Life Course of Mentorship: Stages, Evolution and Transitions Mentoring Across Differences I Mentoring Across Differences II Giving and Receiving Feedback & Lessons Learned and Future Steps Mentoring for Leadership Development Mentoring for Innovation in Academic Medicine Mentoring vs Sponsorship “A sponsor: a senior-level champion who believes in your potential and is willing to advocate for you as you pursue that next raise or promotion”. Forget a Mentor, Find a Sponsor: The New Way to FastTrack Your Career by Sylvia Ann Hewlett, Harvard Business Review Press, 2013. SPONSOR Mentor/Sponsor as Advocate Progress in a faculty career depends entirely on having an advocate – someone who will put their mentee’s name forward to: • Journal editors looking for manuscript reviewers • Meeting planners looking for speakers or session moderators • SROs at NIH looking for study section members • Colleagues at other institutions looking for seminar/grand rounds presenters Examples of Best Practices in Mentoring 1. TUSM Department of Biochemistry Mentoring Program 2. TUSM Programs: i. ii. iii. Internal Grant Review Program Dean’s Mentoring of Tenure-Track Faculty Women Faculty Mentoring Award 3. AAMC GFA new members mentoring circles Example 1: TUSM Department of Biochemistry Mentoring Program Program designed and implemented in 2008 by department faculty, who: • Constituted a Mentoring Oversight Committee • Created a Faculty Mentoring Handbook • Coordinated with Dept Chair to assign mentors to tenure-track faculty. Example 1: TUSM Department of Biochemistry Mentoring Program Program’s Successes and Benefits • The handbook was developed into an excellent resource for tenure-track faculty. • Some mentees ‘clicked’ with their assigned mentor and the relationship was positive. • Even mentees who didn’t ‘click’ with their assigned mentor were nudged to find another mentor or mentors. Example 1: TUSM Department of Biochemistry Mentoring Program Program’s Pitfalls and Challenges • Sustainability of the program through a change in Dept Chair, and when the main author of the mentoring handbook left TU. • Mixed success with assigned mentors. • Unrealistic expectation for one mentor to oversee/monitor all mentoring activities for the mentee. Example 2: TUSM Internal Grant Review Program • New program developed by Larry Goldfinger, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Anatomy & Cell Biology • Will provide a formal mechanism for internal grant review by TUSM research faculty, as an optional resource for faculty preparing grants prior to submitting for extramural funding. The goal of this program is to increase success in obtaining research funding, as well as greater integration of the research enterprise at TUSM by connecting faculty with each other’s research. Example 2: TUSM Internal Grant Review Program • The faculty member/PI submits a draft of the grant application to Larry, who identifies a committee of 2 - 3 reviewers from within the School of Medicine. • The reviewers provide written critiques of the draft and are available for discussion with the PI. • Reviewers are awarded points towards their individual annual Faculty Performance Matrix. Example 3: Annual TUSM Women in Medicine Mentoring Award • Ongoing program in 4th year to provide mentor recognition. • This award recognizes and honors a faculty member, male or female, whose outstanding efforts and achievements have promoted the professional success and/or overall quality of life of women at Temple University School of Medicine. • Several nominations received each year, including for men and women, basic science and clinical faculty. Example 3: Annual TUSM Women in Medicine Mentoring Award • All TUSM faculty in any faculty track (Tenure, ClinicianEducator, Research), in any department and of any rank are eligible for nomination. Emeritus faculty are also eligible for nomination. • Nomination Packet includes: A nominating letter detailing the relevant accomplishments of the nominee One additional letter of support A copy of the candidate's curriculum vitae Example 3: Annual TUSM Women in Medicine Mentoring Award • The TUSM Committee on the Status of Women Faculty reviews the nominations and selects the award winner. • The award is presented by the Dean during the Annual Women in Medicine Professional Development Program and is announced to the entire TUSM community. • The award includes a plaque and a prize of $250. Example 4: Dean’s Mentoring of Tenure-Track Faculty at TUSM • New initiative, started this past academic year. • Intent is to provide annual feedback from the Dean following TU-mandated mid-tenure review. • Includes 30-minute face-to-face meeting (March/April) with Dean and Assoc Dean for Faculty Affairs – opportunity for faculty to provide update on their progress since TUSM review of dossier (Nov). • Mid-tenure review rubric used to highlight strengths and weaknesses, in research, teaching and service, relative to standards required for granting of tenure. Example 4: Dean’s Mentoring of Tenure-Track Faculty at TUSM TUSM Mid -Tenure Performance Review Rubric, page 1 Office of Faculty Affairs, Temple University School of Medicine Mid -Tenure Performance Review Rubric Name: _____________________________________________ Year on Tenure Clock: ____________ Department: ________________________________________ Contract Renewal Length: ____________ The purpose of this review is to assist you, the faculty member, in understanding the performance standards required for achieving tenure within the School of Medicine. The rubric is designed to help you identify strengths and weaknesses in your academic credentials, and to develop a plan to address any weaknesses before you must be reviewed for tenure. Performance Standard Outstanding (Clearly on track to meet or surpass requirements for tenure by time of tenure review) Satisfactory (On track to meet requirements for tenure by time of tenure review with continued effort) Unsatisfactory (Not on track to meet requirements for tenure by time of tenure review, yet shows promise) More than one R01 or equivalent grant funded. One R01 grant or equivalent funded. No major grant funding. Grant renewed or continuous funding. More than 2 peerreviewed papers per year in journals with good impact factors. Additional grant applications submitted. 2 peer-reviewed papers per year in journals with good impact factors. Grant applications submitted. Fewer than 2 peerreviewed papers per year in journals with low impact factors. Most papers do not include PhD or postdoctoral advisors as senior authors. Less than half of all papers include PhD or postdoctoral advisors as senior authors. Most or all papers include PhD or postdoctoral advisors as senior authors. 1. RESEARCH Extramural funding obtained Publication record Comments Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board In 2014, the Membership and Nominations Subcommittee of the AAMC’s Group on Faculty Affairs surveyed GFA members to assess their interest in a new member mentoring program and to solicit suggestions about the structure of a mentoring program. Survey responses demonstrated widespread support. The mentoring program was developed to achieve two goals: 1) to orient new GFA members to the GFA and the AAMC; and 2) to educate GFA members about available resources. Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board • The year-long mentoring program is administered through six mentoring circles which consist of two mentors and six to eight mentees. • Each mentoring circle holds one in-person meeting at the GFA’s Professional Development Conference (PDC) and eight meetings by teleconference. • The teleconferences include a structured curriculum on GFA and AAMC resources, including the AAMC website, the GFA listserv, GFA subcommittees and other relevant programs. Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board • During the 2014 GFA Professional Development Conference (PDC) we sponsored an orientation session for participants who had signed up for the mentoring program as either a mentor or mentee through a preconference e-mail survey. • Those participants were pre-assigned by the M&N subcommittee to 4 mentoring circles. • In response to interest and attendance by new members who had not participated in the pre-conference survey, we created 2 additional mentoring circles ‘on-the-fly’ at the beginning of the orientation session. Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board The orientation session clarified the goals and expectations of the mentoring program and facilitated interpersonal connections within each mentoring circle. Agenda I. Introductions: M&N Subcommittee II. Overview of the Mentoring Program III. Ice Breaker IV. Getting Started: Expectations V. Making the most of the GFA meeting VI. Summary: Questions and Comments Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board Orientation Agenda Item II. Overview: The GFA Pilot Mentoring Program has three main goals to be achieved over the year-long program Mentoring program goals Monthly phone meetings Phone meeting time greetings engage with colleagues learn about GFA get involved with GFA expectations build group operations GFA topic of the month resources research sc plan/dev sc open questions PDC M&N sc comm sc wrap-up data FF program wrap-up Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board Orientation Agenda Item III. Ice Breaker: TELL ME ABOUT… • Your first job • An accomplishment that you are especially proud of • A hobby • A major project that you are doing Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board Orientation Agenda Item IV. Getting Started: Expectations Clarity of Expectations is a critical aspect of effective mentoring relationships • State expectations • Clarify meaning • Reality check - Determine which expectations are reasonable for this year • Reach agreement Dissatisfaction results from unmet expectations Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board Examples of Expectations • Everyone in the group gets time to contribute • Our conversations should be productive • I expect to make connections as a result of my participation • I expect to get personal coaching for challenges at my office • I expect to learn about resources helpful to my institution’s goals At your tables, discuss your expectations for the Mentoring Program and how to make the most from the mentoring experience Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board GFA Pilot Mentoring Program Orientation - July 17, 2014 Evaluation Responses 1=Poor 1 2=Below Avg. 3=Avg 4=Above Avg 5=Excellent Please rate the quality of your overall experience during this GFA Pilot Mentoring Program orientation session 1=Strongly Disagree 2=Disagree 3=Neither Agree nor Disagree 4=Agree 5= Strongly Agree Averaged Score (n=30) 4.3 Averaged Score (n=30) 2 The session helped me understand the goals of the GFA Mentoring Program 4.5 3 The session helped me understand the proposed schedule of topics for the GFA Mentoring Program 4.3 4 The session allowed sufficient time for me to meet the mentors and mentees in my Mentoring Circle 4.2 5 I understand the expectations of me in the GFA Mentoring Program for the coming year 4.4 6 The session helped me express my hopes and expectations for the GFA Mentoring Program for the coming year 4.4 7 The session was helpful in providing strategies to make the most of the GFA Professional Development Conference 4.3 Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board Follow-Up Surveys • We surveyed mentors and mentees six months after the PDC. • The survey responses: • indicate a high level of participation by a majority of the mentees in 5 out of the 6 mentoring circles. • reflect new members’ appreciation for having a mechanism to actively engage at their first GFA meeting. • suggest that these mentees plan to continue to be engaged in GFA activities for at least the coming year. • We will survey mentors and mentees again at the end of the program. Example 5: The GFA Mentoring Program – Helping New Members On Board AAMC GFA M&N Subcommittee Members and Coauthors on Pilot Mentoring Project Steve Block, Wake Forest school of Medicine Heather Brod, The Ohio State University Medical Center College of Medicine Barbara Chadwick, Association of American Medical Colleges Laura Fentem , Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center Elena Fuentes-Afflick, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine Jennifer Hagen, University of Nevada School of Medicine Helen Pearson, Temple University School of Medicine Craig Porter, Medical College of Wisconsin Luanne Thorndyke, University of Massachusetts Medical School Conclusions • Effective mentoring strategies can take many forms. • Some strategies are easily transferable between institutions and types of programs, whereas others are less so. • Mentoring strategies for women and URM may be different. • A big challenge is always sustainability of a mentoring program. A note of caution: “The effectiveness of mentoring in promoting the professional growth of junior faculty is based more on assumption that on demonstrated empirical evidence” (Berk et al. , 2005) Wishing you the best of luck in your mentoring endeavors! Thanks for your attention!