CASE OF DRAGOJEVIC v. CROATIA

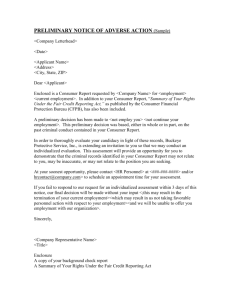

advertisement