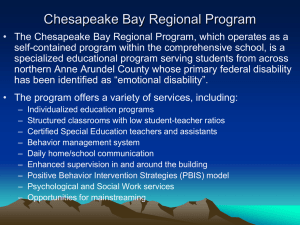

Chesapeake Bay Prese..

advertisement

Chesapeake Bay The word Chesepiooc is a Native American word commonly believed to mean “Great Shellfish Bay” or “Great Water”. Quick Facts: Geography • Drains all or parts of six states, Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, and all of the District of Columbia. • Largest estuary in the United States: – Watershed area 64,000 mi2 – Bay area is 4,000 mi2 (so huge watershed to bay area ratio) – Bay is approximately 200 miles long. – Width varies from 3.4 miles to 35 miles near the mouth of the Potomac River. – Very shallow - average depth is 21 feet. – Bay and its tidal tributaries have around 11,684 miles of shoreline (more than the entire West Coast). • Largest rivers flowing into the bay, from north to south, are: Susquehanna River, Patapsco River, Choptank River, Patuxent River, Potomac River, Rappahannock River, York River, and James River. States drained by the Chesapeake Bay watershed Quick Facts: Water • The Chesapeake holds more than 18 trillion gallons of water. • Receives about half of its water volume from the Atlantic Ocean, the rest drains into the Bay from the watershed. • Eight to 90 percent of the freshwater entering the Bay comes from the northern and western sides. The remaining 10 to 20 percent is contributed by the Eastern Shore. • Fifty major tributaries pour water into the Chesapeake every day. • The Susquehanna River provides about 50% of the freshwater coming into the Bay. • Salinity ranges from freshwater (0-0.5 parts per thousand or ppt) near the Susquehanna River to water of nearly oceanic salinity (3035 ppt) at the Chesapeake's mouth. Chesapeake Bay watershed & sub-basins Quick Facts: Environment and Economy • Value of the Bay estimated to be above a trillion! • The Bay supports more than 3,600 species of plants, fish and animals, including 348 species of finfish, 173 species of shellfish and over 2,700 plant species. It is home to 29 species of waterfowl and is a major resting ground along the Atlantic Migratory Bird Flyway. • The Chesapeake is a commercial and recreational resource for the more than 16 million people who live in its basin. • Produces 500 million pounds of seafood per year. • Bay has two of the five major North Atlantic ports in the United States (Baltimore and Hampton Roads). • Everyone in the watershed lives just a few minutes from one of the more than 100,000 streams and rivers that drain into the Bay. • The Chesapeake was the first in the nation to be targeted for restoration as an integrated watershed and ecosystem. Chesapeake Bay History Bay formation and early inhabitants • 9000 B.C. – Sea level rise from melting glaciers fills the lower Susquehanna valley and begins forming the Chesapeake Bay (at the end of the last Ice Age). • Native tribes arrive in the Bay region. • 2000 B.C. – The Bay assumes its current shape. • 1000 B.C. – Native American agriculture begins. Crops include corn, squash, beans and tobacco. European contact and colonization 1500-1775 • 1500s – Spanish and French explorers reach the Bay. • 1607 – The first permanent New World English settlement is established in Jamestown, Virginia. John Smith, a member of its governing council, begins his exploration of the Bay. • 1650s – The Colonists establish booming businesses in ship masts and timber. Quickly develop agriculture economies, able to sustain their new colonies. Clear land for agriculture and use, tobacco becomes main export item. • 1750 – Colonial population reaches 380,000 persons. 20-30% of forests are stripped for settlements. • 1775 – Colonial population reaches 700,000 persons. • Most scholars agree that the first centuries of contact between Indians, Europeans and Africans resulted in the greatest environmental change in the region since the last Ice Age. Trees cut for planting, lumber, and charcoal production erosion sedimentation. Water impoundments behind mill dams breeding ground for mosquitoes diseases (malaria, yellow fever). First invasive species start being transported to the bay area. • • • 1775 – 1820 period • 1800 – Population reaches 1,000,000 persons. • 1813 – Oyster raking begins in the Bay. • 1817 – Baltimore Gas Lighting Company, nation’s first gas company. • Expanding cities and harbors, major infrastructure (roads, dams, bridges), first commercial steamboats on the bay more sedimentation, sewer and animal waste, air pollution from burning coal. 1820 – 1880 period • 1832 - 1835 – First imported fertilizers are used improved plantation agriculture. • 1850 – Population exceeds 1.8 million. • Oyster industry becomes big business. • Oyster war between traditional oystermen (tongs) and those who use dredging techniques led to 1868 Oyster Navy (worked to enforce anti-dredging laws). • 1880 – Oyster breeding stocks severely threatened. • Industrialization, urban growth, transportation improvements radically transformed Chesapeake Bay landscape. • Farmers cleared 40-50% of the land for planting fields. • Untreated sewage from cities water pollution. Oyster Tongers Skipjack Urbanization 1880-1930 • 1880s – Skipjack boats first produced. • 1890 – 60% of watershed forests are cleared. • 1900 – Population reaches 3 million. less than 30% of the watershed’s original forest remains • 1914 – City of Baltimore is the last major American city to install sewer lines, but one of the first to adopt a waste treatment system. System is installed based on it’s ability to save valuable oyster beds. • 1920 – Population exceeds 4.5 million. • • Pollution is intensified. Wetlands are drained to create more farmlands and to destroy breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Poultry farms starting becoming more prevalent. • Chesapeake Metropolis 1930-2000 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1930 – Population of region reaches 5 million. 1940 – Population nears 5.5 million. 1945 – Widespread use of chemical fertilizers begins. Human population explodes, and the suburb is born. 1967 – Chesapeake Bay Foundation is created (private environmental organization). 1970s – Commercial catches of striped bass dropped from 15 to 2 million pounds per year. Major anoxic zones discovered. 1972 – Clean Water Act is passed. 1973 – Senator Charles Matthias of Maryland begins supporting studies to assess the anthropogenic impacts on the Bay. 1980 – Chesapeake Bay Commission, a tri-state legislative body, is created. 1983 – Chesapeake Bay Program is established after Agreement is signed. 1984 – Chesapeake Bay water quality monitoring program is initiated by the CBP. 1986 – Bay program initiates its first nutrient management efforts. 1987 – Chesapeake Bay agreement is signed. 1990 – Population reaches 10.5 million. 2000 – Population reaches 12 million. Chesapeake 2000 Agreement is signed. Only 1.2 million of the original 3.5 million acres of wetland remain. Impervious surface map for 2000 for the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Source: Woods Hole Research Center. Chesapeake Bay Program “Partnership” • In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Congress funded scientific and estuarine research of the Bay, and the findings pinpointed three areas that required immediate attention: nutrient over-enrichment, dwindling underwater Bay grasses and toxic pollution. • The Chesapeake Bay Program was established with the signing of The 1983 Chesapeake Bay Agreement, to restore and protect the Bay. It is a unique regional partnership that directs and conducts the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay. • CBP partners include the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia; the District of Columbia; the Chesapeake Bay Commission, a tri-state legislative body; the Environmental Protection Agency, representing the federal government; and participating citizen advisory groups, academia and non-profit organizations. • Program Structure: designed to encourage collaboration. Members from partner organizations participate in a series of committees that drive and implement the Bay Program's efforts. • Three main types of committees: – committees that govern the Bay Program and guide policy changes – advisory committees that provide external perspectives on current issues and events – subcommittees that work internally to coordinate restoration activities Chesapeake Bay Agreement • The Agreement serves as the framework for the multi-jurisdictional Chesapeake Bay Program. • The 1983 Chesapeake Bay Agreement, was signed by MD, PA, VA, DC, EPA, CBC, after research In the late 1970s and early 1980s pinpointed significant environmental and ecological degradation. The agreement marked the formation of the Chesapeake Bay Program whose goal is to restore and protect the Bay. • The 1987 Chesapeake Bay Agreement established the Bay Program's goal to reduce the amount of controllable nutrients-primarily nitrogen and phosphorous-that enter the Bay by 40% by 2000 (based on 1985 measurements). • In 1992, the Bay Program partners agreed to continue the 40 percent reduction goal beyond 2000 and to attack nutrients at their source, upstream, in the Bay's tributaries. To help meet this goal, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia developed tributary strategies: river-specific cleanup plans for reducing the nutrients and sediment that flow into the Chesapeake Bay. • Chesapeake 2000, a Bay agreement intended to guide restoration activities throughout the Bay watershed through 2010 sets goals to remove all nutrient and sediment impairments within the Bay by 2010. • In addition to identifying key measures necessary to restore the Bay, Chesapeake 2000 provided the opportunity for Delaware, New York and West Virginia to become more involved in the Bay Program partnership. These headwater states now work with the Bay Program to reduce nutrients and sediment flowing into rivers from their jurisdictions (but not signatories of the 2000 Agreement). Chesapeake Bay Commission “Legislative Arm” • The Chesapeake Bay Commission was created in 1980 (MD and VA only) to coordinate Bayrelated policy across state lines and to develop shared solutions. The catalyst for its creation was the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) landmark seven-year study (1976-1983) on the decline of the Chesapeake Bay. PA became a member in 1985. • As a signatory, the Commission serves as the legislative arm of the Chesapeake Bay Program and is fully involved in all Bay Program policy and implementation decisions. • Mission: The Chesapeake Bay Commission is a tri-state legislative commission which represents and advises the General Assemblies of Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania in cooperatively managing the Chesapeake Bay. • Charged with: - identifying concerns requiring inter jurisdictional coordination and cooperation; - collecting, analyzing, and disseminating information pertaining to the region and its resources for the respective legislative bodies; - recommending legislative and administrative actions necessary to encourage effective and cooperative management of the Bay; - representing the common interests of the member states as they are affected by the activities of the federal government; - providing an arbitration forum to serve as an advisory mediator for conflicts among the states. • Organization: comprised of 21 members - 15 legislators (5 per state) - 3 Governor cabinet members (1 per state) - 3 citizen representatives (1 per state) Chesapeake Bay Foundation “Save the Bay” • Founded in 1967, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) is the largest privately funded, non-profit organization dedicated solely to protecting and restoring the Chesapeake Bay. • Fights for strong and effective laws and regulations. CBF also works cooperatively with government, business, and citizens in partnerships to protect and restore the Bay. • Mission: mission is to restore and sustain the Bay's ecosystem by substantially improving the water quality and productivity of the watershed and to maintain a high quality of life for the people of the Chesapeake Bay region. • Focus areas: - reduce pollution - protect natural resources - restore habitat and replenish fish stocks - educate, inspire and engage constituents to take action for the Bay. • CBF measures the health of the Bay in its annual “State of the Bay” Report by evaluating 12 key health indicators: wetlands, forested buffers, underwater grasses, resource lands, toxics, water clarity, phosphorus and nitrogen, dissolved oxygen, crabs, rockfish, oysters and shad. State of the Bay • • • • • • • Agriculture accounts for 1/4 of land Bay ranks in the top 10% in the US in terms of manure related nitrogen runoff, leaching and loadings from confined livestock and poultry operations. Some areas in S.E. Pennsylvania and S. Virginia are in the upper 10 % of watersheds in use of commercial nitrogen fertilizer. Developed land is 9% of watershed area Population growth is over 1 million per 10 years. While population has increased by 8% in past decade impervious cover has increased by 41% and vehicle miles traveled rose 26%. Forest only covers 58 % of the basin (forest is destroyed at a rate of 100 acres/day). Nutrients and sedimentation are the 2 major issues in the Bay today. Source: Chesapeake Bay Watershed Model Source: Chesapeake Bay Watershed Model Varying dissolved oxygen levels and overall fish catch in the Chesapeake Bay through July, 2003. Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science. During peak summer months, the Chesapeake hypoxic zone has grown to encompass a volume of 11 billion m3. As much as 40% of the Bay in some years has either too little oxygen to support fish and shellfish or not at all. Environmental and economic effects • Major fish and shellfish populations have suffered serious declines (shad, blue crabs, menhaden and oysters). • Virginia crab harvests: – 1984 over 50 million pounds – 2003 just over 21 million pounds Virginia oyster harvests: – 1984 over 4 million pounds – 2003 just over 77,000 pounds • • Stripped bass have rebounded, but half the population is affected by disease. • Underwater grass beds cover only 1/3 of the area they did a few decades ago. Modest improvements in 1980s, but total acreage has remained stagnant since. • Natural filters (oyster reefs and grass beds) have severely diminished. • On land natural filters (forests and wetlands) have also decreased in acreage. Nitrogen sources: Urban has the weakest significance level. Land-to-water delivery: Soil permeability was the only significant factor (weakly significant). Q: Why such low significance? A: Lack of data for statistical detail. Instream loss: All are significant. Smaller streams have the highest parameter because there is higher decay in smaller streams. Nutrient generation is particularly high in areas of south-central Pennsylvania, central Maryland and Virginia, and eastern shore of Maryland and Delaware. (Incremental yields). Delivered yields are much lower than incremental yields for many reaches particularly those that are far from the Bay, because as travel times increase there is a greater potential for instream loss. High potential for delivery exists in areas close to the Bay that have short travel times so little potential for instream loss. Also, watershed units associated with large reaches which have lower estimated loss rates so less instream loss. Point sources are most important in major urban areas where large sewage treatment plants discharge into stream reaches. Agricultural sources are more widely dispersed. Mean annual TN, NO3 export 12.00 10.00 Export (kg N/ha) 8.00 TN NO3 6.00 4.00 2.00 0.00 Pond Baisman's Villanova Carroll Park Gwynnbrook Glyndon Dead Run site No development Most developed Export distribution varies with land cover 1 0.10 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0.75 % NO 3 - load 5.28 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0.5 4.37 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0.25 Pond Branch (forested reference) Baismans Run (suburban) Dead Run (urban) 0 0.01 0.1 1 q (mm/d) 10 100 Results: Export distribution and development • Area of watershed in open development is most significant land cover variable – Increasing area in open development leads to greater proportion of NO3, TN export occurring at high flows • Open development – “mostly vegetation in the form of lawn grasses…most commonly large-lot single family housing units, parks, golf courses, and vegetation planted in developed settings” (NLCD 2002) Export timing across a stream network Duration curves and climate variation Pond Branch (forested reference) •Duration curves show variation between wet and dry years 1 0.08 kg NO3-N/ha/yr % NO 3 - load 0.75 NO3-- 0.03 kg N/ha/yr •Variation is greater in less disturbed catchments 2004 2003 2002 0.5 0.25 •Most urban catchment displays very minimal variation 0.21 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0 0.01 0.1 1 10 100 q (mm/d) Baismans Run (Suburban) Dead Run (urban) 1 9.02 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0.75 NO3-- 1.42 kg N/ha/yr 0.5 2004 2003 2002 7.29 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 7.69 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0.75 % NO 3 - load % NO 3 - load 1 1.83 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 2004 2003 2002 0.5 0.25 0.25 7.45 kg NO3-N/ha/yr 0 0 0.01 0.1 1 q (mm/d) 10 100 0.01 0.1 1 q (mm/d) 10 100 Impact of climate variation on dischargeconcentration relationship Pond Branch (forested reference) [NO 3 - ] (mg/L) 0.30 0.20 2002 2003 2004 0.10 0.1 1 10 •Shifts are not explained by difference in flow duration alone •Ecological processes also part of the equation 0.00 0.01 •Concentration-discharge relationship exhibits interannual shifts 100 q (mm/d) Dead Run (urban) Baismans Run (suburban) 3.00 2.00 2004 2003 2002 1.00 0.1 2.00 2002 2003 2004 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.01 [NO 3 - ] (mg/L) [NO 3 - ] (mg/L) 3.00 1 q (mm/d) 10 100 0.01 0.1 1 q (mm/d) 10 100