Language Activities

advertisement

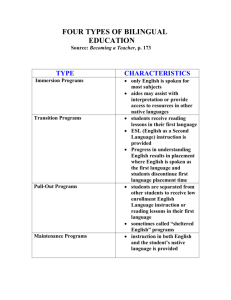

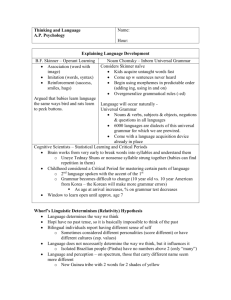

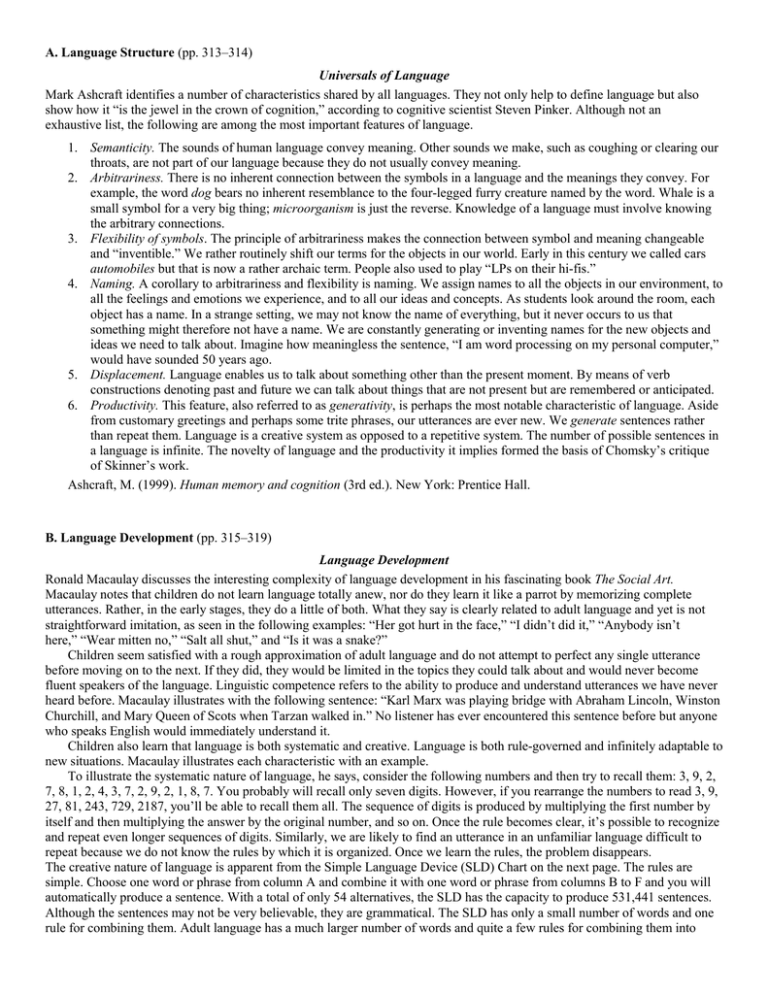

A. Language Structure (pp. 313–314) Universals of Language Mark Ashcraft identifies a number of characteristics shared by all languages. They not only help to define language but also show how it “is the jewel in the crown of cognition,” according to cognitive scientist Steven Pinker. Although not an exhaustive list, the following are among the most important features of language. 1. Semanticity. The sounds of human language convey meaning. Other sounds we make, such as coughing or clearing our throats, are not part of our language because they do not usually convey meaning. 2. Arbitrariness. There is no inherent connection between the symbols in a language and the meanings they convey. For example, the word dog bears no inherent resemblance to the four-legged furry creature named by the word. Whale is a small symbol for a very big thing; microorganism is just the reverse. Knowledge of a language must involve knowing the arbitrary connections. 3. Flexibility of symbols. The principle of arbitrariness makes the connection between symbol and meaning changeable and “inventible.” We rather routinely shift our terms for the objects in our world. Early in this century we called cars automobiles but that is now a rather archaic term. People also used to play “LPs on their hi-fis.” 4. Naming. A corollary to arbitrariness and flexibility is naming. We assign names to all the objects in our environment, to all the feelings and emotions we experience, and to all our ideas and concepts. As students look around the room, each object has a name. In a strange setting, we may not know the name of everything, but it never occurs to us that something might therefore not have a name. We are constantly generating or inventing names for the new objects and ideas we need to talk about. Imagine how meaningless the sentence, “I am word processing on my personal computer,” would have sounded 50 years ago. 5. Displacement. Language enables us to talk about something other than the present moment. By means of verb constructions denoting past and future we can talk about things that are not present but are remembered or anticipated. 6. Productivity. This feature, also referred to as generativity, is perhaps the most notable characteristic of language. Aside from customary greetings and perhaps some trite phrases, our utterances are ever new. We generate sentences rather than repeat them. Language is a creative system as opposed to a repetitive system. The number of possible sentences in a language is infinite. The novelty of language and the productivity it implies formed the basis of Chomsky’s critique of Skinner’s work. Ashcraft, M. (1999). Human memory and cognition (3rd ed.). New York: Prentice Hall. B. Language Development (pp. 315–319) Language Development Ronald Macaulay discusses the interesting complexity of language development in his fascinating book The Social Art. Macaulay notes that children do not learn language totally anew, nor do they learn it like a parrot by memorizing complete utterances. Rather, in the early stages, they do a little of both. What they say is clearly related to adult language and yet is not straightforward imitation, as seen in the following examples: “Her got hurt in the face,” “I didn’t did it,” “Anybody isn’t here,” “Wear mitten no,” “Salt all shut,” and “Is it was a snake?” Children seem satisfied with a rough approximation of adult language and do not attempt to perfect any single utterance before moving on to the next. If they did, they would be limited in the topics they could talk about and would never become fluent speakers of the language. Linguistic competence refers to the ability to produce and understand utterances we have never heard before. Macaulay illustrates with the following sentence: “Karl Marx was playing bridge with Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, and Mary Queen of Scots when Tarzan walked in.” No listener has ever encountered this sentence before but anyone who speaks English would immediately understand it. Children also learn that language is both systematic and creative. Language is both rule-governed and infinitely adaptable to new situations. Macaulay illustrates each characteristic with an example. To illustrate the systematic nature of language, he says, consider the following numbers and then try to recall them: 3, 9, 2, 7, 8, 1, 2, 4, 3, 7, 2, 9, 2, 1, 8, 7. You probably will recall only seven digits. However, if you rearrange the numbers to read 3, 9, 27, 81, 243, 729, 2187, you’ll be able to recall them all. The sequence of digits is produced by multiplying the first number by itself and then multiplying the answer by the original number, and so on. Once the rule becomes clear, it’s possible to recognize and repeat even longer sequences of digits. Similarly, we are likely to find an utterance in an unfamiliar language difficult to repeat because we do not know the rules by which it is organized. Once we learn the rules, the problem disappears. The creative nature of language is apparent from the Simple Language Device (SLD) Chart on the next page. The rules are simple. Choose one word or phrase from column A and combine it with one word or phrase from columns B to F and you will automatically produce a sentence. With a total of only 54 alternatives, the SLD has the capacity to produce 531,441 sentences. Although the sentences may not be very believable, they are grammatical. The SLD has only a small number of words and one rule for combining them. Adult language has a much larger number of words and quite a few rules for combining them into acceptable utterances. This is the challenge that confronts infants as they begin the long task of becoming fluent speakers of the language spoken by those around them. Macaulay, R. (1994). The social art. New York: Oxford University Press. Bilingualism Two-thirds of the world’s children are raised as bilingual speakers; however, less than 7 percent of U.S. citizens are bilingual. In additive bilingualism, people master a second language with no loss of their first language. As Margaret Matlin explains, English speakers in Quebec typically learn French because they operate a business. In subtractive bilingualism, the second language replaces the first language. Historically, North American schools pressured children of immigrants to learn English but only rarely encouraged children to remain fluent in their first language. One of the important predictors of learning a second language is a person’s attitude toward its native speakers. For example, English Canadian students’ attitudes toward French Canadians was just as important as their cognitive, language-learning aptitude in determining how well they learned French. The predictors go both ways. Those elementary school English Canadian students who learned French developed more positive attitudes toward French Canadians than did children who remained monolingual. One reason North American schools did not encourage retention of the first language among immigrant children was the accepted notion that bilingualism led to deficits in thinking. Presumably, the cognitive effort required to master and maintain two languages diminished the child’s capacity to learn and store other things. The first carefully controlled scientific studies suggested just the opposite. Bilinguals were more advanced in school, performed better on tests of first-language skills, and showed greater mental flexibility. The findings have been replicated in research around the world. In her overview of the relevant research literature, Matlin notes that bilinguals seem to have a number of important advantages over monolinguals, including the following: 1. Bilinguals show greater expertise in their first (native) language. English-speaking Canadian children whose classes are taught in French gain greater understanding of English language structure. Bilinguals also are more likely to recognize that a word like rainbow has two morphemes and preschool bilingual children are likely to under-stand that a printed symbol represents a word. 2. Those using two languages are also more likely to appreciate the phonological components of language. 3. Bilinguals are better at paying attention to the more subtle aspects of a language task, ignoring more obvious linguistic characteristics. For example, they are more likely to recognize that the semantically incorrect “The cat barks” is grammatically correct. 4. Bilinguals also recognize that the names assigned to concepts are arbitrary. They are more likely to understand that a cow could just have easily been called a deer. On many measures of metalinguistic skills (knowledge about the form and structure of language) bilinguistic children outperform their monolinguistic counterparts. 5. Bilingual children are better at following complicated instructions and are also more sensitive to certain pragmatic features of languages. English-speaking children whose classes are taught in French are more aware that, when you speak to a blindfolded child, you need to supply additional information. 6. Bilinguals tend to perform better on tests of creativity. Bilingual children perform better on concept-formation tasks, tests of nonverbal intelligence, and on problem-solving tasks requiring that they ignore irrelevant information. Matlin, M. W. (2009). Cognition (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Language You need to be sure you master each of the following elements of language. Read about each aspect of language structure, development and theory and choose one activity to complete from the list. 1. How can you describe the basic structural units of a language, including the rules that enable us to communicate meaning? Language is our way of combining words to communicate meaning. Spoken language is built from basic speech sounds, called phonemes; elementary units of meaning, called morphemes; and words. Finally, language must have a grammar, a system of rules that enables us to communicate with and understand others. Semantics refers to the rules we use to derive meaning from the morphemes, words, and sentences; syntax refers to the rules we use to order words into grammatically sensible sentences. In all 6000 human languages, the grammar is intricately complex. ACTIVITY CHOICES choose one: Write a poem about the structural units of language. Create a diagram about the structural units of language. Create an Anatomy of Language visual that demonstrates your understanding of the structural units of language. 2. How can you trace the course of language acquisition from the babbling stage through the twoword stage? Children’s language development moves from simplicity to complexity. Their receptive language abilities mature before their productive language. Beginning at about 4 months, infants enter a babbling stage in which they spontaneously utter various sounds at first unrelated to the household language. By about age 10 months, a trained ear can identify the language of the household by listening to an infant’s babbling. Around the first birthday, most children enter the one-word stage, and by their second birthday, they are uttering two-word sentences. This two-word stage is characterized by telegraphic speech. This soon leads to their uttering longer phrases (there seems to be no “three-word stage”), and by early elementary school, they understand complex sentences. ACTIVITY CHOICES choose one: Create a visual flow-chart of language acquisition. For each stage create a superhero complete with a costume, powers and purpose/mission to demonstrate your understanding of language acquisition. Write several sounds/words/phrases/sentences for each stage that you think you might have uttered in your language development. 3. What are Skinner’s and Chomsky’s contributions to the nature-nurture debate over how children acquire language, and explain why statistical learning and critical periods are important concepts in children’s language learning? The debate between the behaviorist view that emphasizes learning and the view that each organism comes with innate predispositions surfaces again in theories of language development. Representing the nurture side of the argument, behaviorist B. F. Skinner argued that we learn language by the familiar principles of association (of sights of things with sounds of words), imitation (of words and syntax modeled by others), and reinforcement (with success, smiles, and hugs after saying something right). Challenging this claim, and representing the nature side of the debate, Noam Chomsky notes that children are biologically prepared to learn words and use grammar (they are born with what Chomsky called a language acquisition device already in place). He argues that children acquire untaught words and grammar at too fast a rate to be explained solely by learning principles. Moreover, there is a universal grammar that underlies all human language. Cognitive neuroscientists suggest that the statistical analysis that children perform during life’s first years is critical for the mastery of grammar. Skinner’s emphasis on learning helps explain how infants acquire their language as they interact with others. Chomsky’s emphasis on our built-in readiness to learn grammar helps explain why preschoolers acquire language so readily and use grammar so well. Nature and nurture work together. Childhood does seem to represent a critical (or “sensitive”) period for certain aspects of learning. Research indicates that children who have not been exposed to either a spoken or signed language by about age 7 gradually lose their ability to master any language. Learning a second language also becomes more difficult after the window of opportunity closes. For example, adults who attempt to master a second language typically speak it with the accent of their first. ACTIVITY CHOICES choose one: Use a Venn Diagram to compare and contrast Skinner and Chomsky’s views on language acquisition. Create a parallel story board/comic strip with at least 3 scenes; one for Skinner’s views of language acquisition and one for Chomsky’s views of language acquisition. Create a language acquisition Facebook page with 3 comments/videos/pic posts from Skinner and 3 comments/videos/pic posts from Chomsky. Linguists estimate that 6800 languages exist in the world today (about one dies out every two weeks). 250 languages are spoken by more than 1 million people. Eighty-three languages are spoken by 80 percent of the world’s people. About 3500 languages are spoken by 0.2 percent of the world’s population. Only 600 languages have speaking populations robust enough to support their survival past the end of the century. Languages need at least 100,000 speakers to survive the ages, reports the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 66 percent of the world’s children are raised as bilingual speakers. Only 6.3 percent of U.S. residents are bilingual. In snapshots of language losses worldwide, World -watch Institute reports the following: Eighty percent of the 260 native languages still spoken in the United States and Canada are not being learned by children. Eyak, native to the coast of Alaska’s Prince William Sound, had one remaining speaker—88-year-old Marie Smith, who lamented “It’s horrible to be alone. I have a lot of friends. I have all kinds of children, yet I have no one to speak to” in Eyak. Marie died on January 21, 2008. In South America, hundreds of languages died as a result of the Spanish conquest. Of the remaining 640, 80 percent are spoken by fewer than 10,000 people. Many languages from the Amazon region have fewer than 500 speakers. Arikapu has only six. In Africa, the birthplace of nearly a third of the world’s languages, 54 are believed dead and 116 more are nearing extinction. In Europe, nearly 90 percent of Russians speak Russian, the language enforced during the Soviet era. As a result, most of the country’s 100 other native languages, most of them Siberian, including Udihe, are near extinction.