DOCX file of Higher education in Australia (0.78 MB )

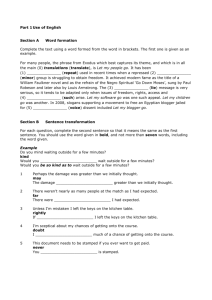

advertisement