PW-12-18 - Three Trusts

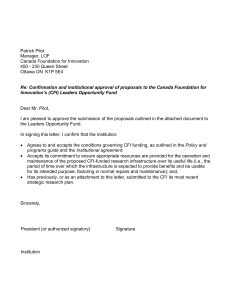

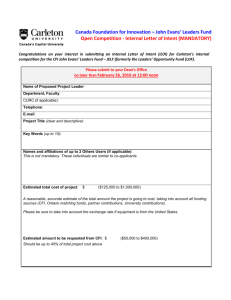

advertisement