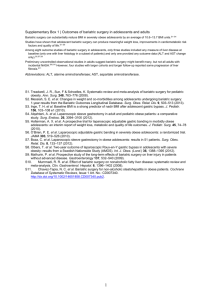

Eating Disorders

advertisement