Overall, the strong evidence for oral

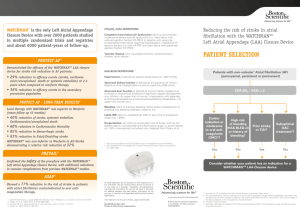

advertisement

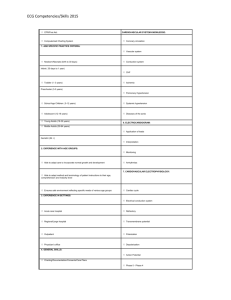

Online only section In this online section of our current opinion paper, we discuss differences in the three guideline sets (1-9) in more detail split by the different domains of atrial fibrillation management (10), i.e. Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation Antithrombotic therapy Rate control, and Rhythm control. Definition and diagnosis of AF. All guidelines define AF by its pathophysiology of fibrillating electrical activation in the atria, and all require an electrocardiogram that documents the arrhythmia to confirm the diagnosis. All three sets of guidelines recommend an initial work-up that encompasses a 12-lead ECG and an echocardiogram to search for accompanying heart disease. In Europe, the echocardiogram is recommended only in patients who show signs for heart disease (Table 1), while the Canadian guidelines routinely recommend an echocardiogram for all patients with AF, partly reflecting the usual local management pathway of AF patients in Europe and Canada. Based on the increased stroke risk in patients with “silent”, undetected AF (11), the focused update of the European guidelines recommends an active opportunistic screening for AF in all persons over 65 years of age, similar to the AHA guidelines for stroke prevention (12). This recommendation is not given by CCS or ACCF/AHA/HRS. Antithrombotic therapy. Stroke risk stratification and decision for anticoagulation. Since 2001, the European and US AF guidelines recommend oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF patients at risk for stroke (13, 14). This recommendation is based on a large body of evidence from trials comparing vitamin K antagonists with aspirin, a combination of antiplatelet agents, and placebo for stroke prevention in AF (15), and was recently reinforced by a comparison of the new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) apixaban and aspirin (16). All guideline sets recommend oral anticoagulation for patients at high risk for stroke as identified by the “CHADS2 risk factors” comprising the clinical risk factors age of 75 years or older, survived stroke or transient ischemic attack (counted double), congestive heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes (Tables 2, 2a). All guidelines agree that patients with two of more of these clinical risk factors should receive oral anticoagulation. Approximately one third of AF patients are not considered at high risk of stroke by the original CHADS2 classification (17, 18). In these patients, there has been a shift towards recommending oral anticoagulation for most patients, especially when other risk factors are present. This is reflected in the 2010 ESC guidelines and in their update in 2012, and in the CCS guidelines. By nature, the focussed update of the ACCF/AHA/HRS in 2011 only commented on new medications, and did not cover changing indications for anticoagulant therapy in detail. The best evaluated “additional risk factors” are age of 65 – 74 years, presence of vascular disease, and female gender (19, 20). The ESC recommends the use of oral anticoagulation when these factors are present (unless “female gender” is the only risk factor), and formalizes this assessment into the so-called CHA2DS2VASc score (21). The 2006 ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines recommend a similar assessment, albeit not formalised in a score, but rather listed as “less validated risk factors.” Unlike the ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines, the CCS recommends oral anticoagulation in preference to aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with only one of the CHADS2 risk factors, in line with the focussed update of the ESC guidelines. The CCS reflects the differential relevance of the additional or “VASc” risk factors by recommending a graded use of anticoagulation depending on the individual factors: When age is > 65 years, or both vascular disease plus female sex are present, oral anticoagulation should be used. Aspirin is suggested for patients with a single risk factor (vascular disease or female sex). The use of these additional “VASc” risk factors (CCS terminology) and the CHA2DS2VASc score (ESC wording) has recently been validated in different cohorts (20, 22). The ESC update states that female sex on its own should not be considered a risk factor, supported by a recent large cohort analysis from Denmark (19), and does not recommend any anticoagulant therapy in such patients, while CCS and ACCF/AHA/HRS suggest that aspirin be considered. The ESC also introduces an assessment of bleeding risk on anticoagulant therapy, and suggests the treatment of risk factors for bleeding, adaptation of the choice of anticoagulant, and/or intensification of clinical monitoring of patients at increased bleeding risk (21). Figure 1 depicts the similarities and differences between the three guideline sets in the decision to recommend oral anticoagulant therapy. Overall, the strong evidence for oral anticoagulation in high-risk patients is reflected in all three sets of guidelines. There are differences in the recommended antithrombotic therapy in patients at low to moderate risk for stroke, reflecting the lack of controlled trials specifically conducted in such patients, their relatively low absolute stroke risk, and the resulting large number of patients needed to treat for the prevention of each event. These differences in recommendations illustrate that there are evidence gaps at the “lower end” of stroke risk, e.g. in patients with only one of the CHADS2 or VASc risk factors. Use of new oral anticoagulants (NOAC). Between 2009 and 2011, the final results of four large randomised trials comparing the oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (23) and the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban (24) and apixaban (16, 25) to warfarin (23-25) or aspirin (16) have been published. These substances are referred to as “new oral anticoagulants” in the ESC and CCS guidelines update. These medications offer a clinical choice of different oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in AF. Based on the trial results without much additional “real-world” information, all three guideline writing groups recommend the new oral anticoagulants alongside vitamin K antagonists for stroke prevention in AF. The 2010 ESC guidelines only covered dabigatran in a long footnote, reflecting that trial data were available, but that the drug was not approved for clinical use in Europe at that time. The updated ACCF/AHA/HRS Guidelines, reacting quickly to FDA approval of dabigatran after the publication of the RELY trial (23), included a recommendation for dabigatran as an alternative to warfarin for patients with AF. Choosing an oral anticoagulant for stroke prevention in AF. While the new anticoagulants are recommended in all three guidelines, the ESC and CCS express a preference for anticoagulation using one of the NOACs rather than a vitamin K antagonist (Class IIa recommendation in the ESC guideline, comparable grade (“suggest”) in the CCS guideline), based on their better safety profile in the large trials and the potentially higher efficacy. The ACCF/AHA/HRS update recommends NOACs (dabigatran) as an alternative to vitamin K antagonists. The focussed update of the ESC guidelines (21) and the update of the CCS guidelines (6), both published in 2012, recommend one of three NOACs (apixaban [pending approval], dabigatran, rivaroxaban) as a preferred alternative to warfarin for oral anticoagulation in AF, based on the superiority or at least equivalence to warfarin in stroke prevention, the reduced rate of intracranial hemorrhage, and the convenience of the new agents. Despite the much-debated perceived differences in their effectiveness – based entirely on indirect comparisons across the different trials - none of the guidelines chose to put forward recommendations to prefer one of the new oral anticoagulants over another. The recommended doses of the NOACs rather reflect their regionally approved dosing, which varies. This results in marked differences in the recommended dose in some of the NOACs, and also limits the use of specific NOACs in selected patient groups (see below). Therapy of AF patients with concomitant unstable coronary artery disease. All three guideline sets recommend the addition of antiplatelet therapy to oral anticoagulation in AF patients with a recent myocardial infarction or unstable coronary artery disease, and in those receiving a coronary stent (26, 27). The ESC and CCS issued separate sets of recommendations for patients with AF undergoing stent implantation. These recommendations acknowledge the higher bleeding risk in patients receiving a combination of aspirin and oral anticoagulation compared to patients on oral anticoagulation alone, but nonetheless recognise the need for combination therapy in patients at risk for stroke in AF and at risk for coronary thrombosis. Both guidelines recommend so-called “triple therapy” of aspirin, clopidogrel and an oral anticoagulant for a short time after a myocardial infarction or placement of a stent, and the use of bare metal stents to reduce the period needed for such “triple therapy.” The ESC specifically recommends radial access for AF patients in need for vascular interventions. Rate control All three sets of guidelines integrate the insights gained from the RACE II trial into their rate control recommendations (28). At first sight, the recommendations appear to be somewhat different, but on further analysis, they are fairly similar. The ACCF/AHA/HRS guideline states that treatment to achieve strict rate control is not beneficial (Class III recommendation), provided that the patient has stable ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction >0.40) and no or acceptable symptoms, and recognizes that uncontrolled tachycardia may cause a reversible decline in ventricular performance. The European guideline advocates an initial strategy of lenient rate control (Class IIa recommendation, rate < 110 bpm), with a switch to a strict rate control strategy if symptoms persist or tachycardiomyopathy occurs. The CCS also recommends an initial lenient rate control approach, but recognizes that only 22% of patients in the RACE II study had resting heart rates between 100-110 bpm. As such, a more careful deviation from the prior, stricter rate control recommendations was chosen and a slightly lower target heart rate < 100 bpm is recommended in symptomatic patients. After the publication of the PALLAS trial (29) which showed detrimental effects of dronedarone in patients with permanent AF, both ESC and CCS included a recommendation not to use dronedarone in patients with permanent AF, i.e. as a rate controlling agent. There were no other major changes in rate control management recommended in the three sets of guidelines, and the recommendations for rate control are very comparable (Table 3). Rhythm control After six controlled trials of “rhythm versus rate control” in AF, rhythm control therapy is currently recommended only for patients whose symptoms are not well controlled by rate control alone. The Canadian and European guidelines state explicitly that the primary purpose of antiarrhythmic therapy is to reduce arrhythmia-related symptoms. This indication for any rhythm control intervention is also implicit in the “old” 2006 ACC/AHA/ESC recommendations, and has not been changed by the focussed update of ACCF/AHA/HRS. The ESC in 2010 and the CCS in 2011 chose to further emphasise that the indication for adding rhythm control therapy on top of rate control therapy should be based on symptoms by introducing dedicated symptom scores: The EHRA score (Europe) or the largely overlapping CCSSAF score (Canada). All three guidelines discuss the choice and purpose of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and the place of catheter ablation in the management of recurrent forms of AF. In 2010, the European guidelines fell in with previous proposals and included an additional time-based category of longstanding-persistent AF (1). This term re-designates an arrhythmia that had lasted more than one year when a decision has been made that it is appropriate for an attempt at rhythm control. Other categories of AF remained unchanged. This is not reflected in the CCS or ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines. Both the US update and the ESC guideline adapted the recommendations for specific rhythm control interventions based on new data: Dronedarone was introduced in the ESC guidelines and in the CCS guidelines as an antiarrhythmic drug with a low proarrhythmic potential (30-33). The US guidelines also endorsed the use of dronedarone in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, but recommended its use for the prevention of cardiovascular hospitalizations. Similar to the US update, dronedarone is recommended to prevent cardiovascular hospitalisations in the ESC guidelines (Class IIa, LoE B). Although not specifically mentioned as an antiarrhythmic drug in the recommendations, the intended use of dronedarone as an antiarrhythmic agent is evident from the rhythm control flow chart in the US update (Figure 2). There are some differences in the patient populations deemed suitable for dronedarone therapy. In the European guidelines, dronedarone is recommended for recurrent AF in patients without heart disease, in those with left ventricular hypertrophy, and in patients with coronary artery disease. This is largely in line with the 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focussed update with the exception of patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, where the use of dronedarone is not recommended in the ACCF/AHA/HRS update (Figure 2). All guidelines already warned against the use of dronedarone in severe (NYHA class IV, or recently decompensated) heart failure in 2010, based on the outcomes of the ANDROMEDA trial (34). The European Guidelines also discourage the use of dronedarone in patients with NYHA III heart failure (Figure 2B), whereas the US guidelines state a caution in the use of dronedarone “in the presence on a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 35%,” reflecting one of the inclusion criteria of the ANDROMEDA trial (34). The updates of the CCS and ESC guidelines integrate the new information from the PALLAS trial demonstrating deleterious effects of dronedarone therapy in patients with permanent AF (29). Based on this information, the ESC focussed updates recommends against the use of dronedarone in permanent AF (class III recommendation), and discourages the use of dronedarone in patients with heart failure unless there is no alternative. The CCS limits the use of dronedarone to patients without a history of heart failure and with preserved systolic heart function (LVEF > 40%). This reliance on echocardiography to define systolic heart failure is a consistent pattern in the CCS guidelines, while the other two sets of guidelines use the same clinical definitions, often without echocardiographic assessment, as were employed in the clinical trials to define heart failure. In addition, the CCS suggested that dronedarone be used with caution in patients taking digoxin, based on a potential interaction between digitalis glycosides, dronedarone, and adverse outcomes in the PALLAS trial. In summary, dronedarone remains a recommended antiarrhythmic agent in patients without heart disease, including patients with left ventricular hypertrophy and in patients with coronary artery disease, while its use is discouraged in most patients with heart failure with variable definitions of unsuitable patients, reflecting different regulatory situations and the uncertainty surrounding dronedarone’s safety in patients with light and moderate heart failure. Vernakalant has recently been approved for pharmacological cardioversion of AF in Europe. The intravenous formulation of vernakalant converts recent-onset AF (3537) and is recommended as an alternative to other agents for pharmacologic cardioversion in patients with little or no underlying structural heart disease, and in some patients with structural heart disease (hypertensive heart disease and chronic ischaemic heart disease) as an alternative to amiodarone. Since vernakalant is not available in the USA or Canada, it is not considered in the US or Canadian guidelines. Duration of antiarrhythmic drug therapy after cardioversion. The focussed update of the ESC guidelines also recommends considering short-term antiarrhythmic drug therapy after cardioversion of AF as a safer, though slightly inferior, alternative to long-term therapy based on the results of the Flec-SL trial (38). This information was not available at the time of the updates of the CCS and ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines, and was therefore not considered. The increasing evidence-base for the prevention of recurrent AF after catheter ablation (predominantly pulmonary vein isolation) is reflected in all three guidelines (39-43). The Canadian task force recommended catheter ablation as a secondary rhythm control therapy after failure of antiarrhythmic drug therapy (Class IIa). In 2011, the ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines issued a class I recommendation for catheter ablation to improve symptoms related to AF in patients with paroxysmal AF and minimal or no heart disease, provided that the patient was refractory to antiarrhythmic drugs and the ablation was carried out by an expert in an experienced centre. This approach was also reflected in a recent European/American consensus document (44) and in the 2012 focussed update of the ESC guidelines (21). Both the European and the Canadian guideline writers introduced the concept of proceeding directly to ablation (Class IIa by the ESC focussed update, IIb in Canada and in the ESC 2010 document) as an alternative to antiarrhythmic drug therapy in patients with paroxysmal AF and little or no heart disease, based on accumulating recent evidence. Disclosures. All authors were involved in the writing of the most recent versions of the guidelines on AF management issued by ESC (JC, PK) and ACCF/AHA/HRS (AC, SW) and CCS (ACS,AMG). All authors have received honoraria for advising or speaking for companies involved in the development of drugs and devices relevant to the management of AF. AG has not received honoraria in the past 17 months, since taking on her current role as president-elect and president of HRS. Details of our disclosures are published in the relevant AF management guidelines or professional society web pages. online references: 1. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010; 31: 2369-429. 2. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH, Vahanian A, Auricchio A, Bax J, Ceconi C, Dean V, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hobbs R, Kearney P, McDonagh T, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Vardas PE, Widimsky P, Agladze V, Aliot E, Balabanski T, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Capucci A, Crijns H, Dahlof B, Folliguet T, Glikson M, Goethals M, Gulba DC, Ho SY, Klautz RJ, Kose S, McMurray J, Perrone Filardi P, Raatikainen P, Salvador MJ, Schalij MJ, Shpektor A, Sousa J, Stepinska J, Uuetoa H, Zamorano JL, Zupan I. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Europace. 2010; 12: 1360-420. 3. Gillis AM, Verma A, Talajic M, Nattel S, Dorian P. Canadian Cardiovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines 2010: rate and rhythm management. Can J Cardiol. 2011; 27: 47-59. 4. Verma A, Macle L, Cox J, Skanes AC. Canadian Cardiovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines 2010: catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter. Can J Cardiol. 2011; 27: 60-6. 5. Cairns JA, Connolly S, McMurtry S, Stephenson M, Talajic M. Canadian Cardiovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines 2010: prevention of stroke and systemic thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation and flutter. Can J Cardiol. 2011; 27: 74-90. 6. Skanes AC, Healey JS, Cairns JA, Dorian P, Gillis AM, McMurtry MS, Mitchell LB, Verma A, Nattel S. Focused 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society atrial fibrillation guidelines: recommendations for stroke prevention and rate/rhythm control. Can J Cardiol. 2012; 28: 125-36. 7. Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, 3rd, Ezekowitz MD, Jackman WM, January CT, Lowe JE, Page RL, Slotwiner DJ, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57: 1330-7. 8. Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, Ellenbogen KA, Lowe JE, Estes NA, 3rd, Page RL, Ezekowitz MD, Slotwiner DJ, Jackman WM, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM, Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Le Heuzey JY, Crijns HJ, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Halperin JL, Tamargo JL, Kay GN. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Focused Update on the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (Updating the 2006 Guideline) A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57: 223-42. 9. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Le Huezey JY, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann LS. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57: e101-98. 10. Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Van Gelder IC, Bax J, Hylek E, Kaab S, Schotten U, Wegscheider K, Boriani G, Brandes A, Ezekowitz M, Diener H, Haegeli L, Heidbuchel H, Lane D, Mont L, Willems S, Dorian P, Aunes-Jansson M, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borentain M, Breitenstein S, Brueckmann M, Cater N, Clemens A, Dobrev D, Dubner S, Edvardsson NG, Friberg L, Goette A, Gulizia M, Hatala R, Horwood J, Szumowski L, Kappenberger L, Kautzner J, Leute A, Lobban T, Meyer R, Millerhagen J, Morgan J, Muenzel F, Nabauer M, Baertels C, Oeff M, Paar D, Polifka J, Ravens U, Rosin L, Stegink W, Steinbeck G, Vardas P, Vincent A, Walter M, Breithardt G, Camm AJ. Comprehensive risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation: emerging diagnostic and therapeutic options--a report from the 3rd Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace. 2012; 14: 8-27. 11. Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, Lau CP, Fain E, Yang S, Bailleul C, Morillo CA, Carlson M, Themeles E, Kaufman ES, Hohnloser SH. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 120-9. 12. Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, Appel LJ, Braun LT, Chaturvedi S, Creager MA, Culebras A, Eckel RH, Hart RG, Hinchey JA, Howard VJ, Jauch EC, Levine SR, Meschia JF, Moore WS, Nixon JV, Pearson TA. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011; 42: 517-84. 13. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Asinger RW, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Frye RL, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Klein WW, Levy S, McNamara RL, Prystowsky EN, Wann LS, Wyse DG. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2001; 22: 1852-923. 14. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Asinger RW, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Frye RL, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Klein WW, Levy S, McNamara RL, Prystowsky EN, Wann LS, Wyse DG, Gibbons RJ, Antman EM, Alpert JS, Faxon DP, Gregoratos G, Hiratzka LF, Jacobs AK, Russell RO, Smith SC, Alonso-Garcia A, BlomstromLundqvist C, De Backer G, Flather M, Hradec J, Oto A, Parkhomenko A, Silber S, Torbicki A. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in Collaboration With the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38: 1231-66. 15. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Adjusted-dose warfarin versus aspirin for preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147: 590-2. 16. Connolly S, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener HC, Hart R, Golitsyn S, Flaker G, Avezum A, Hohnloser S, Diaz R, Talajic M, Jun Z, Pais P, Budaj A, Parkhomenko A, Jansky P, Commerford P, Tan RS, Sim KH, Lewis BS, Van Meighem W, Lip GYH, Kim JH, Lanas-Zanetti F, Gonzalez-Hermosillo A, Dans AL, Munawar M, o'Donnel M, Lawrence J, Lewis GD, Afzal R, Yusuf S. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364: 806-17. 17. Nabauer M, Gerth A, Limbourg T, Schneider S, Oeff M, Kirchhof P, Goette A, Lewalter T, Ravens U, Meinertz T, Breithardt G, Steinbeck G. The Registry of the German Competence NETwork on Atrial Fibrillation: Patient characteristics and initial management. Europace. 2009; 11: 423-34. 18. Nieuwlaat R, Olsson SB, Lip GY, Camm AJ, Breithardt G, Capucci A, Meeder JG, Prins MH, Levy S, Crijns HJ. Guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment is associated with improved outcomes compared with undertreatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2007; 153: 1006-12. 19. Friberg L, Benson L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Assessment of female sex as a risk factor in atrial fibrillation in Sweden: nationwide retrospective cohort study. Bmj. 2012; 344: e3522. 20. Olesen JB, Lip GY, Hansen ML, Hansen PR, Tolstrup JS, Lindhardsen J, Selmer C, Ahlehoff O, Olsen AM, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. Bmj. 2011; 342: d124. 21. Camm AJ, Lip GYH, Atar D, de Caterina R, Hohnloser S, Savelieva I, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P. 2012 Focused Update of the ESC Guidelines on the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012; published on line 25 August 2012: 22. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182 678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33: 1500-10. 23. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361: 1139-51. 24. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365: 883-91. 25. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, LopezSendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365: 981-92. 26. Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Hart RG, Hohnloser SH, Pfeffer M, Chrolavicius S, Yusuf S. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 2066-78. 27. Lip GY, Huber K, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Airaksinen JK, Cuisset T, Kirchhof P, Marin F. Antithrombotic management of atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing coronary stenting: executive summary--a Consensus Document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2010; 31: 1311-8. 28. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, Hillege HL, Bergsma-Kadijk JA, Cornel JH, Kamp O, Tukkie R, Bosker HA, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van den Berg MP. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362: 1363-73. 29. Connolly SJ, Camm AJ, Halperin JL, Joyner C, Alings M, Amerena J, Atar D, Avezum A, Blomstrom P, Borggrefe M, Budaj A, Chen SA, Ching CK, Commerford P, Dans A, Davy JM, Delacretaz E, Di Pasquale G, Diaz R, Dorian P, Flaker G, Golitsyn S, Gonzalez-Hermosillo A, Granger CB, Heidbuchel H, Kautzner J, Kim JS, Lanas F, Lewis BS, Merino JL, Morillo C, Murin J, Narasimhan C, Paolasso E, Parkhomenko A, Peters NS, Sim KH, Stiles MK, Tanomsup S, Toivonen L, Tomcsanyi J, Torp-Pedersen C, Tse HF, Vardas P, Vinereanu D, Xavier D, Zhu J, Zhu JR, Baret-Cormel L, Weinling E, Staiger C, Yusuf S, Chrolavicius S, Afzal R, Hohnloser SH. Dronedarone in High-Risk Permanent Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 30. Touboul P, Brugada J, Capucci A, Crijns HJ, Edvardsson N, Hohnloser SH. Dronedarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation: a dose-ranging study. Eur Heart J. 2003; 24: 1481-7. 31. Singh BN, Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, Roy D, Kowey PR, Capucci A, Radzik D, Aliot EM, Hohnloser SH. Dronedarone for maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutter. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357: 987-99. 32. Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van Eickels M, Gaudin C, Page RL, Torp-Pedersen C, Connolly SJ. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360: 668-78. 33. Le Heuzey J, De Ferrari GM, Radzik D, Santini M, Zhu J, Davy JM. A short-term, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dronedarone versus amiodarone in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: the DIONYSOS study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010; 21: 597-605. 34. Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, McMurray JJ, Gotzsche O, Levy S, Crijns H, Amlie J, Carlsen J. Increased mortality after dronedarone therapy for severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358: 2678-87. 35. Kowey PR, Dorian P, Mitchell LB, Pratt CM, Roy D, Schwartz PJ, Sadowski J, Sobczyk D, Bochenek A, Toft E. Vernakalant hydrochloride for the rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009; 2: 652-9. 36. Roy D, Pratt CM, Torp-Pedersen C, Wyse DG, Toft E, Juul-Moller S, Nielsen T, Rasmussen SL, Stiell IG, Coutu B, Ip JH, Pritchett EL, Camm AJ. Vernakalant hydrochloride for rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation. 2008; 117: 1518-25. 37. Camm AJ, Capucci A, Hohnloser SH, Torp-Pedersen C, Van Gelder IC, Mangal B, Beatch G. A randomized active-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of vernakalant to amiodarone in recent-onset atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57: 313-21. 38. Kirchhof P, Andresen D, Bosch R, Borggrefe M, Meinertz T, Parade U, U. R, Samol A, Steinbeck G, Treszl A, Wegscheider K, Breithardt G. Comparing short-term and long-term antiarrhythmic drug therapy after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation - a prospective, randomised, open, blinded outcome assessment trial. Lancet. 2012; published on line 18th June 2012, DOI:10.1016/S01406736(12)60570-4: 39. Khan MN, Jais P, Cummings J, Di Biase L, Sanders P, Martin DO, Kautzner J, Hao S, Themistoclakis S, Fanelli R, Potenza D, Massaro R, Wazni O, Schweikert R, Saliba W, Wang P, AlAhmad A, Beheiry S, Santarelli P, Starling RC, Dello Russo A, Pelargonio G, Brachmann J, Schibgilla V, Bonso A, Casella M, Raviele A, Haissaguerre M, Natale A. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359: 1778-85. 40. Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, Cappato R, Chen SA, Crijns HJ, Damiano RJ, Jr., Davies DW, Haines DE, Haissaguerre M, Iesaka Y, Jackman W, Jais P, Kottkamp H, Kuck KH, Lindsay BD, Marchlinski FE, McCarthy PM, Mont JL, Morady F, Nademanee K, Natale A, Pappone C, Prystowsky E, Raviele A, Ruskin JN, Shemin RJ, Calkins H, Brugada J, Chen SA, Prystowsky EN, Kuck KH, Natale A, Haines DE, Marchlinski FE, Calkins H, Davies DW, Lindsay BD, McCarthy PM, Packer DL, Cappato R, Crijns HJ, Damiano RJ, Jr., Haissaguerre M, Jackman WM, Jais P, Iesaka Y, Kottkamp H, Mont L, Morady F, Nademanee K, Pappone C, Raviele A, Ruskin JN, Shemin RJ. HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: Recommendations for Personnel, Policy, Procedures and Follow-Up: A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed and Approved by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2007; 9: 335-79. 41. Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, Davies W, Iesaka Y, Kalman J, Kim YH, Klein G, Natale A, Packer D, Skanes A, Ambrogi F, Biganzoli E. Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010; 3: 32-8. 42. Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, De Paola A, Marchlinski F, Natale A, Macle L, Daoud EG, Calkins H, Hall B, Reddy V, Augello G, Reynolds MR, Vinekar C, Liu CY, Berry SM, Berry DA. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010; 303: 333-40. 43. Calkins H, Reynolds MR, Spector P, Sondhi M, Xu Y, Martin A, Williams CJ, Sledge I. Treatment of atrial fibrillation with antiarrhythmic drugs or radiofrequency ablation: two systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009; 2: 349-61. 44. Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, Brugada J, Camm AJ, Chen SA, Crijns HJ, Damiano RJ, Jr., Davies DW, Dimarco J, Edgerton J, Ellenbogen K, Ezekowitz MD, Haines DE, Haissaguerre M, Hindricks G, Iesaka Y, Jackman W, Jalife J, Jais P, Kalman J, Keane D, Kim YH, Kirchhof P, Klein G, Kottkamp H, Kumagai K, Lindsay BD, Mansour M, Marchlinski FE, McCarthy PM, Mont JL, Morady F, Nademanee K, Nakagawa H, Natale A, Nattel S, Packer DL, Pappone C, Prystowsky E, Raviele A, Reddy V, Ruskin JN, Shemin RJ, Tsao HM, Wilber Wedge D, Prystowsky EN, Damiano R, Jr., Jackman WM, Marchlinski F, McCarthy P, Wilber D, Ad N, Cummings J, Gillinov AM, Heidbuchel H, January C, Lip G, Markowitz S, Nair M, Ovsyshcher IE, Pak HN, Tsuchiya T, Shah D, Siong TW, Vardas PE. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: Recommendations for Patient Selection, Procedural Techniques, Patient Management and Follow-up, Definitions, Endpoints, and Research Trial Design: A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2012; 45. Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener HC, Goette A, Hindricks G, Hohnloser S, Kappenberger L, Kuck KH, Lip GY, Olsson B, Meinertz T, Priori S, Ravens U, Steinbeck G, Svernhage E, Tijssen J, Vincent A, Breithardt G. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: executive summary: Recommendations from a consensus conference organized by the German Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork (AFNET) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur Heart J. 2007; 28: 2803-17. 46. Dorian P, Cvitkovic SS, Kerr CR, Crystal E, Gillis AM, Guerra PG, Mitchell LB, Roy D, Skanes AC, Wyse DG. A novel, simple scale for assessing the symptom severity of atrial fibrillation at the bedside: the CCS-SAF scale. Can J Cardiol. 2006; 22: 383-6. Online Tables: Online Table 1: Recommendations for diagnosis and initial management ESC/EHRA/EACTS ACCF/AHA/HRS CCS ECG recording of AF mandatory for diagnosis No explicit recommendations, text consistent with ESC recommendations. EHRA / CCS-SAF score not mentioned (was not published in 2006). ECG recording of AF mandatory for diagnosis EHRA symptoms score (45, 46)* Prolonged ECG monitoring to detect AF CCS-SAF symptoms score (45, 46) Prolonged ECG monitoring to detect AF Holter ECG for safety (rate control) Holter ECG for safety (rate control) Referral to a cardiologist when symptomatic or with complications Referral to a cardiologist when symptomatic or with complications Structured, specialistprepared follow-up Underlying, reversible causes esp. hypertension and sleep apnea should be sought * The EHRA score and the CCS-SAF symptoms score largely overlap. Online Table 2A: Factors included in stroke risk estimation ESC ACCF/AHA/HRS CCS Congestive Heart Failure Yes yes Yes LVEF ≤ 35% not specifically stated, implicit in CHF yes Yes Hypertension Yes yes Yes Age ≥ 75 yes, strong yes, strong Yes Age 65-74 Yes less validated Yes Diabetes mellitus Yes yes Yes Prior Stroke yes, strong yes, strong Yes Vascular Disease Yes less validated Yes Sex Category (female) Yes less validated Yes Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy yes, strong implicit implicit Mitral valve disease yes, strong yes, strong yes Thyrotoxicosis Implicit less validated implicit Online Table 2B: Recommended antithrombotic therapy based on stroke risk ESC ACCF/AHA/HRS CCS 1 high risk factor OAC OAC OAC (prior stroke or age ≥ 75 years) NOAC preferred over VKA NOAC or VKA NOAC preferred over VKA 2 or more risk factors OAC OAC OAC NOAC preferred over VKA NOAC or VKA NOAC preferred over VKA OAC OAC OAC NOAC preferred over VKA NOAC or VKA NOAC preferred over VKA OAC or ASA, OAC preferred OAC or ASA If age > 65, OAC. If female or vascular disease, ASA ASA Nothing 2 risk factors* 1 risk factor NOAC preferred over VKA No risk factors Nothing OAC oral anticoagulation; VKA vitamin K antagonists; NOAC new oral anticoagulants, ASA aspirin. High risk factors: survived stroke or transient ischemic attack, age 75 years or above. Other risk factors: congestive heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, female sex (ESC: unless female sex is the sole risk factor), age 65-74 years, vascular disease / coronary artery disease *Table 13 in the US guidelines (9) is not explicit as to whether the less validated risk factors (female sex, age 65-74, or coronary artery disease) are to be counted within the “moderate” risk factors, but the text clearly classifies them as moderate risk factors. Online Table 2C. Detailed recommendations for antithrombotic therapy based on stroke risk. Abbreviations as follows: AF atrial fibrillation, ASA acetyl salicylic acid, DES drugeluting stent. INR international normalized ratio, OAC oral anticoagulant therapy. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, VKA vitamin K antagonist therapy. *apixaban is recommended after approval by EMA/Health Canada. ESC ACCF/AHA/HRS CCS Antithrombotic therapy for all patients, except lone AF or patients with contraindications (IA) Selection of antithrombotic agents should be based on absolute risk for stroke and bleeding, and relative risk and benefit for a given patient (IA) In patients at high risk for stroke, oral anticoagulation with either a VKA (INR 23) or one of the NOACs (apixaban*, dabigatran, rivaroxaban) are recommended (IA). In patients at high risk for stroke, VKA (INR2-3) are recommended (IA), INR >2.5 in patients with mechanical valves (IB) A NOAC should be considered rather than VKA therapy (IIa A). In patients at high risk for stroke (CHADS≥2), OAC are recommended (Strong, IA). Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban* suggested over VKA (INR 2-3) when OAC is recommended (Conditional IIa) In patients with one “major” (age >75, prior stroke/TIA) or more than 1 “clinically relevant nonmajor” risk factor (age 6574 yrs, hypertension, heart failure, impaired LV function, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, female sex), VKA is recommended (IA) VKA is recommended in patients with more than one moderate risk factor (age >75 yrs, hypertension, heart failure, impaired LV function, diabetes mellitus, IA) OAC is recommended for most with one “major” risk factor (CHADS2=1, Strong (IA)) In patients with one “clinically relevant nonmajor” risk factor (see prior line for risk factors), VKA is receommended based on risk assessment and individual therapy suitability (IIaA) In patients with one moderate risk factor (see prior line for risk factors), ASA or VKA can be chosen based on risk assessment and individual therapy suitability (IIaA) Patients with no “major” risk factors (CHADS2=0) but age > 65, or both vascular disease and female sex, OAC is suggested (Conditional, IIaC) Patients with no “major” risk factors (CHADS2=0) but one of vascular disease or female sex, ASA is suggested (Conditional, IIaC) In patients with one or more of the less validated risk factors age 65-74, female gender, or coronary artery disease, either aspirin or VKA is recommended (IIaB) Implicit (recommended in section 3) Antithrombotic therapy decisions are independent of the type of AF (IIaB) Implicit INR monitoring weekly initially, then monthly (IA) Interruption of OAC for a short time (high stroke risk: max 48 hrs) is acceptable to perform surgical procedures (IIaC). Resumption of OAC on the evening of surgery when hemostasis is adequate (IIaC) Interruption of VKA therapy is reasonable for up to 1 week for vascular or surgical procedures (IIaC) Interruption of OAC for a short time is based on stroke risk and bleeding risk (IIaC) With high risk of stroke (mech valve, recent TIA/stroke CHADS2≥3) either continue OAC (low bleeding risk) or bridge with LMWH. With low or moderate risk of stroke (CHADS2≤2) and high risk of bleeding, interruption of OAC suggested. If low risk of bleeding, continue OAC (Conditional, IIaC) Re-evaluation of the need for anticoagulation at regular intervals (IIaC) Atrial flutter should be treated like AF (IC) No antithrombotic therapy is a reasonable therapeutic VKA is not recommended in lone AF (<50 yrs without No antithrombotic therapy is a reasonable strategy in patients at truly “lone” AF (<65 yrs, no risk factors, IIaC) Patients receiving stents while in need for OAC should receive a bare metal stent. After implantation, combination therapy with OAC, ASA, and clopidogrel is recommended (IIaC, partly IIbC) heart disease or any stroke risk factors, III) therapeutic strategy in patients at truly “lone” AF (<65 yrs, no risk factors, IIaC) ASA 81 – 325 mg is an alternative in low-risk patients or those with contraindications (IA) ASA 81 – 325 mg is an alternative in low-risk patients (CHADS2≤1) or those with contraindications (IA) Patients receiving stents while in need for OAC should receive a bare metal stent. After implantation, combination therapy with OAC and clopidogrel is recommended. (IIbC). Patients receiving stents while in need for OAC should receive a bare metal stent. After implantation, combination therapy with OAC and clopidogrel is recommended. ASA (triple therapy) may be needed for 1 month in high stroke risk group (CHADS2≥2) (IIbC) Duration of combination therapy Duration of combination therapy bare metal stent 1 month -limus DES 3 months -taxel DES 6 months - acute coronary syndromes with or without PCI: 3-6 months ESC recommends a longer duration of dual combination (up to 12 Duration of combination therapy bare metal stent 1 month bare metal stent 1 month -limus DES 3 months -taxel DES 6 months -limus DES 3 months -taxel DES 6 months acute coronary syndromes without PCI: If CHADS2≤1 ASA+clopidigrel up to 12 months. If CHADS2≥2 therapy as PCI. months) of clopidogrel and OAC. Careful monitoring of INR during combination therapy Careful monitoring of INR during combination therapy Careful monitoring of INR during combination therapy Patients suffering a stroke while on OAC should be considered for higher INR therapy (3.0-3.5, IIb) Patients suffering a stroke while on OAC should be considered for novel OAC with superior efficacy (Implicit) Online Table 3: Recommendations for rate control therapy ESC/EHRA/EACTS ACCF/AHA/HRS CCS Implicit (section 2) assessment by resting ECG in all patients, and by heart rate response to exercise in specific patients. ECG measurement at rest before and during rate control therapy (IB) ECG measurement at rest or Holter before and during rate control therapy (IB) ß blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists for acute rate control (ESC IA, ACCF/AHA/HRS IB, CCS IB) and for chronic rate control (IB) A combination of digoxin and ß blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium antagonist for rate control, dose titration to avoid bradycardia (ESC: IB, ACCF/AHA/HRS, CCS: IIaB) When patients remain symptomatic, heart rate during exercise should be assessed (ESC IC, CCS IB), and a stricter approach to rate control chosen (ESC; IIaB) Digoxin p.o. can be used for resting heart rate control, especially in heart failure patients and sedentary individuals (ESC: IIaC, ACCF/AHA/HRS IC, CCS IIaB) Amiodarone can be used to control rate when other drugs fail (ESC: IIbC, ACCF/AHA/HRS, CCS: IIaC) AV nodal ablation when pharmacotherapy fails (ESC, ACCF/AHA/HRS: IIaB, CCS: IB) Rate control in patients with preexcitation Rate control using propafenone or amiodarone in preexcitation patients (IC) procainamide, disopyramide, ibutilide, or amiodarone in hemodynamically stable patients with preexcitation (IIbB) DC cardioversion, iv procainamide, ibutilide for rapid pre-excited AF (IC) Rate control in patients with heart failure Implicit, no specific recommendation * CCS focused update 2012 Digitalis or amiodarone for acute rate control in heart failure patients IB Digoxin reserved for rate control in sedentary or LV dysfunction (IIaB)