renaissance 3

advertisement

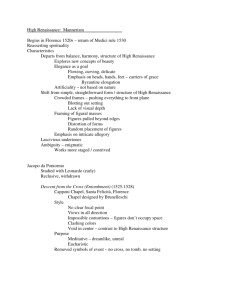

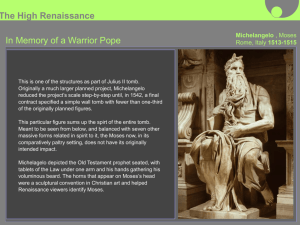

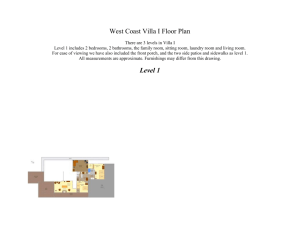

Italian Renaissance with a Touch of Mannerism: the Sequel Andrea Mantegna Giovanni Bellini Sofonista Anguissola Anguissola’s use of natural poses and expressions; her sympathetic, personal presentation; and her graceful treatment of the forms did not escape the attention of her famous contemporaries. She captured ordinary life and put them into portraits. Sofonisba Anguissola created much more relaxed portraiture than Bronzino. Anguissola used strong contours, muted tonality, and smooth finishes. She introduced an informal intimacy of her own. This is a portrait of her family members. Against a neutral ground, she placed her two sisters and brother in an affectionate pose meant not for official display, but for private showing. The sisters, wearing matching striped gowns, flank their brother, who caresses a lap dog. The older sister (left) summons the dignity required for the occasion, while the boy looks quizzically at the portraitist with an expression of naive curiosity and the other girls diverts her attention toward something or someone to the painter’s left. This painting is Parmigianino’s best-known work. He achieved the elegance that was the principal aim of Mannerism. He smoothly combined the influences of Correggio and Raphael in a picture of exquisite grace and precious sweetness. The Madonna’s small oval head, her long slender neck, the unbelievable attention and delicacy of her hands, and the sinuous, swaying elongation of her frame are all marks of the aristocratic, gorgeously artificial taste of a later phase of Mannerism. On the left stands a bevy of angelic creatures, melting with emotions as soft and smooth as their limbs. On the right the artist included a line of columns without capitals- a setting for a figure Parmigianino: Madonna with a scroll, whose distance from the foreground is immeasurable and ambiguous. with a long neck Most Mannerist painters achieved sophisticated elegance by portraiture. The subject is a proud youth -- a man of books and intellectual society rather then a lowly laborer or a merchant. His cool demeanor seems carefully affected, a calculated attitude of nonchalance toward the observing world. It asserts the rank and station but not the personality of the subject. The haughty poise, the graceful long fingered hands, the book, the furniture’s carved faces, and the severe architecture all suggest the traits and environment of the highbred patrician. Bronzino created a muted background for the subject’s sharply defined, asymmetrical Mannerist silhouette that contradicts his impassive pose. Bronzino: Portrait of a Young Man Benvenuto Cellini: Saltcellar of King Francis I of France Lavinia Fontana: Noli Me Tangere Palladio: Villa Rotonda (Venice) The Villa Rotonda is not the typical of Palladio’s villa style. He did not construct it for an aspiring gentleman farmer, but for a retired monsignor who wanted a villa for social events. Palladio planned and designed Villa Rotonda, located on a hill top, as a kind of belvedere, without the usual wings of secondary buildings. It’s central plan with four identical facades and projecting porchesis both sensible and functional. Floor plan of Villa Rotonda MANNERIST ARCHITECTURE: Went against the grain of Renaissance Architecture by using Classical forms in illogical ways This is mostly due to the style being used only for secular purposes Symmetrical but highly ornamental Colossal order “Blind Windows” Bronzino: Allegory with Venus & Cupid Bronzino demonstrated the Mannerist’s fondness for: learned and intricate allegories that often had lascivious (exciting sexual desires) undertones. Cupid is depicted fondling his mother, Venus, while Folly prepares to shower them with rose petals. Time, who appears in the upper right-hand corner, draws back the curtain to reveal the playful incest in progress. Other figures in the painting represent Envy and Inconstancy (unfaithfulness by virtue of being unreliable or treacherous). The masks symbolize deceit. The picture seems to suggest that love, accompanied by envy and plagued by inconstancy is foolish and that lovers will discover its folly in time. But as in many Mannerist paintings the meaning here is ambiguous and interpretations of this painting may vary. The contours are structural and the surfaces smooth. Of special interest are the extremities, (hands, feet, etc.) for the Mannerists considered them carriers of grace and the clever depiction of them evidence artistic skill.