Decision Making and Demand and Supply

Decision-making and Demand and Supply Analysis

Thinking Economically: Marginal Analysis

• Optimization Assumption

: an assumption that suggests that the person in question is trying to maximize some objective

• Marginal Benefit : the increase in the benefit that results from an action

• Marginal Cost : the increase in the cost that results from an action

• Total Net Benefits

: the difference between all benefits and all costs

Marginal Way in Action Simplified

• The Box Example

• If the marginal benefit of an extra unity of the activity is greater than its marginal cost, increasing the activity will increase total net benefits.

• If the marginal cost of an extra unit of the activity is greater than its marginal cost, increasing the activity will decrease total net benefits.

• Therefore, to maximize total net benefits the level of an activity that maximizes total net benefits is where the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost of an extra unit of the activity.

Boxes

• If an extra unit of the activity (trades) results in getting more boxes (MB) than are being given up

(MC) the stack of boxes grows (TNB).

• If an extra unit of the activity (trades) results in getting less boxes (MB) than are being given up

(MC) the stack of boxes shrinks (TNB).

• If an extra unit of the activity (trades) results in getting the same amount of boxes (MB) that are being given up (MC) the stack of boxes is at its tallest ( maximum TNB).

Maximizing Total Net Benefits

• Total Way – select the level of the activity that maximizes the difference between total benefits and total costs

• Marginal Way – set the marginal benefit of to the marginal cost of an extra unit

• Economist prefer the later because many decisions are not all or nothing. Most times people are deciding to increase or decrease the amount of something that they are doing.

Basic Definitions for MB and MC and

Maximization of TNB

• MB=∆TB/ ∆Q=(TB

New

-TB

Old

)/(Q new

-Q old

)

• MC=∆TC/ ∆Q=(TC

New

-TC

Old

)/(Q new

-Q old

)

• TB=∑MB +

(any fixed benefits which we generally assume to be zero)

• TC=∑MC+

(any fixed costs which we generally assume to be zero)

• TNB =TB-TC

• Max TNB at that level of Q where MB=MC

Example of Maximizing TNB

• See Hand out and Excel Spreadsheet

(Maximizing TNB)

Aplia Demand and Supply

Experiment

• The market simulation summarized

– Each buyer had a buyer value (MB of the one book) and each seller a seller cost (MC)

– Both buyer and seller tried to maximize their gain

• Buyer Gain Buyer value – price

• Seller Gain Seller cost – price

– Repeated trials brought about a market price that cleared the market

– As the price approached the market price the total gain to buyers and sellers together increased

• Let´s generalize this by presenting the theory of markets.

Markets: The power of Demand and Supply

• A market is simply an institution that bring buyers and sellers together to agree on price and quantity traded.

• Competitive Markets

– many sellers and buyers →no one buyer or seller affect the price or they are price takers

– identical or homogeneous goods→price is the only decision factor

– perfect information →there is only one price

– free entry and exit →profits (economic) will be zero in the long-run

• Non-Competitive Markets

– Monopoly – one seller

– Oligopoly – few sellers

– Monopolistically Competitive – differentiated products

The Theory of Demand for Goods and Services

• Households or consumers buy goods and services for a variety of reasons, but can we model it?

• Economics assume that individuals are rational – they weigh the costs and benefits of their actions and then try and maximize TNB.

• What are the benefits? Economists have modeled benefits as satisfaction or utility (an injection is useful but usually not pleasant – it provides utility).

• What are the costs? Economist argue that the costs are opportunity costs – i.e. what does one give up to get a good or service.

• A person’s preferences or tastes, along with other factors, determine the benefit from a good.

• The price of the good, the price of similar or substitute goods, a person’s limited income, along with other factors, determine the opportunity costs of the good.

• Basically, the theory of demand is getting the most satisfaction from the goods and service one buys given the prices of goods and one’s income.

• While many factors affect demand, we begin by concentrating on the price of the good. Why? In competitive markets, the price of the good is the MC to the buyer.

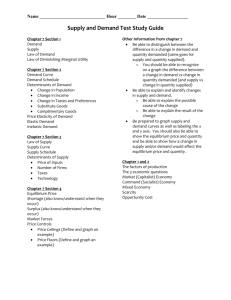

The Law of Demand

•

Law of Demand

– the price of a good and the quantity demanded are negatively (or inversely) related, ceteris paribus (Latin – all other things equal).

• Rational behavior suggests that as the MC↑, ceteris paribus, an individual will ↓Q, it’s that simple.

• Early theorists, however, concentrated on MB rather than

MC. The believed that utility was measurable, so-called cardinal (after numbers) utility.

– Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

– Jelly bean example and Econ U$A tape on the drought in

California.

– If people are to buy more (↑Q), since the MB↓, the price must fall

(↓P)

• More recent theorists use the concept of ordinal utility to come to a similar conclusion. A person is assumed to be able to rank bundles from most preferred to least preferred.

– Reaches the Law of Demand with less restrictive assumptions than cardinal utility.

• The Law if Demand and the

Income and

Substitution Effects

• Substitution Effect : as the price of a good falls its opportunity cost relative to other similar or substitute goods falls, so consumers use more of the good and less of other goods

– Example: P apples

=$1/lb of A ($1/A) and P oranges

($1/O) → the relative price of A in terms of O : P

1 A requires us to give up 1 0. If the P

P

A

/P

O

A

=$1/lb of O

A

/P

O

→ falls to $.5/A, the

→ 1 A requires us to give up only .5 O. Apples are thus cheaper and we buy more apples and less oranges.

Oranges are now more expensive ( 2 A for every 1 O).

• Income Effect: as the price of a good falls, the real purchasing power of income increases and consumers will buy more of the good (if the good is normal).

– Example: If P

A

=$1, A $100 a week of income will allow us to buy 100 A. Or, the real income, measured in apples, is 100 A. If the P

A falls to $.5/A, our real income is now 200 A.

– The effect of incomes on demand is not clear.

For normal goods , increases in income, increase demand, and for inferior goods the opposite happens.

• Cardinal utility, ordinal utility, and MB=MC, all arrive at Law of Demand.

• We now look at the Law of Demand and the

Theory of Demand using numbers/schedules, graphs/curves, and mathematical functions (don’t panic). These representations make it easier to understand the implications of theory, but they require study and practice.

• We will use the book example and then shift to a handout to practice.

Catherine’s Demand Schedule

Figure 1 Catherine’s Demand Schedule and Demand

Curve

Price of

Ice-Cream Cone

$3.00

2.50

1. A decrease in price ...

2.00

1.50

A movement along the curve

1.00

is caused by changes in P only

0.50

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Quantity of

Ice-Cream Cones

2. ... increases quantity of cones demanded.

Copyright © 2004 South-Western

• The Demand Function

– P

R

- Price of related goods

• Complements

• Substitutes

– Y - Income

– N

B

- Number of Buyers (added when all individuals curves are summed together – see market demand)

– T -Tastes

– E -Expectations

– G- Government: Taxes and Subsidies

• In mathematical notation:

– Qd=F (P , P

R

,Y,N

B

,T,E,G), where F() is “related to”

• Signing the determinants of demand. - is an inverse relationship and + is a direct relationship.

• Market Demand Curve: The horizontal summation of all the individual demand curves (handout). In our Aplia experiment, the buyer values were ranked from high to low.

Movements Along vs Shifts of the

Demand Curve

• Demand Curve versus the Demand Function

– The demand curve is created assuming ceteris paribus, so it maps only the relationship between P and Q

D.

– The demand function shows all the determinants of demand. All the factors other than P, such a P

R

• Schedules and Y, are shift factors.

– Changes in price are described by the demand schedule.

– Shifts are shown as increases in Q

D

• Graphs/Curves at every price.

– A movement along the curve is a change in quantity demanded and is only caused by the change in the price of the good itself.

– A shift of the curve is a change in demand is caused by any other factor other than the price of the good itself.

• Qd=F (

P | P

R

,Y,N

B

,T,E,G )

Figure 3 Shifts in the Demand Curve

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

Increase in demand

0

Decrease in demand

Demand curve, D

2

Demand curve, D

3

Demand curve, D

1

Quantity of

Ice-Cream Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Theory of Supply

• Economists assume that businesses are rational as well. We assume their primary interest is maximizing profits .

• Profits are the difference between total revenues and total costs. Revenues are analogous to benefits received by consumers.

• Once again, we concentrate on price first. Why?

In competitive markets, price is equal to MB (or marginal revenue) to firms. Every time the firm sells another unit, its revenue increases by the price of the good.

• Law of Supply - price and the quantity supplied are positively related, ceteris paribus.

– Rational behavior implies that firms try and maximize profits, where the MB = P and MC is dependent on how much output is produced.

– As the P ↑, the MB ↑ → Q supplied ↑ to maximize profits.

• Classical theorist approached the Law of Supply from the costs perspective. They posited that the MC ↑ as Q ↑.

– Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns → LDMR comes from the productivity decline as more and more of a variable input is added to fixed input, eventually the extra output for each additional variable input will fall, ceteris paribus. Thus, MC ↑ of producing additional Q will eventually

• Drilling for oil in Economics U$A video, Dairy Queen example, and growing the world’s food supply in a flower pot.

•

Law of Increasing Costs : as the production of a good increases, its opportunity cost increases (re: PPF and specialized resources)

– Remember that the L of IC occurs because of resource specialization.

• Both the LIC and LDMR predict that as Q ↑ up the productivity of inputs will fall and MC ↑.

• The Law of Supply arises because prices must rise to cover the higher MC of producing additional units of output.

• We can better work with the Law of Supply using schedules, graphs/curves, and mathematical equations.

Ben’s Supply Schedule

Figure 5 Ben’s Supply Schedule and Supply Curve

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

$3.00

1. An increase in price ...

2.50

2.00

1.50

1.00

0.50

Change in

Q s is a movement

And caused only by Price

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Quantity of

Ice-Cream Cones

2. ... increases quantity of cones supplied.

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

• The Supply Function

– P

I

– P

I

- Input prices

-Prices of other outputs

– Te -Technology

– E -Expectations

– N

S

-Number of sellers (occurs when adding individual supply curves together)

– G - Government taxes and subsidies

• Q s

=F(P,P

I

,P

O

,Te,E,N

S

,G)

• Market Supply: The horizontal summation of all the individual firms’ supply curves.

Movements vs. Shifts Again

• Q s

=F( P , P

I

,P

O

,Te,E,N

S

,G )

• The price of the good itself causes movements along the supply curve or changes in the quantity supplied.

• Anything other than the price of the good causes shifts in the supply curve or changes in supply.

• Market supply comes from horizontally adding all the individual supply curves (see handout).

Figure 7 Shifts in the Supply Curve

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

Supply curve, S

3

Supply curve, S

1

Decrease in supply

Supply curve, S

2

Increase in supply

0 Quantity of

Ice-Cream Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Market Equilibrium

• Market – an institution that bring buyers and sellers together to agree upon price and quantity traded.

• Remember buyers key off of price in competitive markets because it is their MC and for sellers it is their MB.

• Equilibrium price and quantity are those that clear the market (neither shortages or surpluses) because the Q d

• Disequilibrium prices and quantities

=Q s.

– Shortage – Excess Demand

– Surplus – Excess Supply

• At the P e and Q e

, buyers and sellers behavior are coordinated.

Figure 8 The Equilibrium of Supply and Demand

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone Supply

$2.00

Equilibrium price

Equilibrium

Equilibrium quantity

Demand

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

Quantity of Ice-Cream Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Figure 9 Markets Not in Equilibrium

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

$2.50

2.00

(a) Excess Supply

Surplus

Supply

0

Demand

4

Quantity demanded

7 10

Quantity supplied

Quantity of

Ice-Cream

Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Figure 9 Markets Not in Equilibrium

(b) Excess Demand

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

$2.00

1.50

Supply

0

Shortage

Demand

4

Quantity supplied

7 10

Quantity demanded

Quantity of

Ice-Cream

Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Figure 10 How an Increase in Demand Affects the

Equilibrium

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

1. Hot weather increases the demand for ice cream . . .

$2.50

2.00

2. . . . resulting in a higher price . . .

0

3. . . . and a higher quantity sold.

7 10

Supply

New equilibrium

Initial equilibrium

D

D

Quantity of

Ice-Cream Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Figure 11 How a Decrease in Supply Affects the

Equilibrium

Price of

Ice-Cream

Cone

S

2

1. An increase in the price of sugar reduces the supply of ice cream. . .

S

1

$2.50

2.00

2. . . . resulting in a higher price of ice cream . . .

New equilibrium

Initial equilibrium

Demand

0 4 7

3. . . . and a lower quantity sold.

Quantity of

Ice-Cream Cones

Copyright©2003 Southwestern/Thomson Learning

Comparative Statics

• Animal tracks help one to tell what kind of an animal and the direction the animal went.

• Demand and supply shifts leave different tracks to help us identify them and whether they are increasing or decreasing.

• Movement of either D or S (confirm with graphs)

– D↓, S constant → P↓, Q↓

– D↑, S constant → P↑, Q↑

– S↓, D constant → P↑, Q↓

– S↑, D constant → P↓, Q↑

Role of Prices

• Price play an important role in markets because it:

– Coordinates buyers and seller behavior

– Provides information about MC and MB

– Rations the good between buyers

– Determines resource allocation

• Although the equilibrium graph is interested it is sterile, we are interested in what happens when circumstances change, i.e. demand and supply shocks (shifts).

Rocking and Rolling: Comparative

Statics

• When either the demand curve or the supply curve shift, P e and Q e change predictably.

• These is done by comparing two static equilibriums or comparative statics.

• Demand Shifts/Shocks:

– D ↑ → P ↑ Q ↑

– D ↓ → P ↓ Q ↓

• Supply Shifts/Shocks:

– S ↑ → P ↓ Q ↑

– S ↓ → P ↑ Q ↓

• Like animals, D and S shocks leave unique tracks.

Using Comparative Statics to Predict or

Explain Market Behavior

• Predicting:

– Demand can increase, remain the same, or decrease.

– Supply can increase, remain the same, or decrease.

– So comparative statics tells us that there are 9 different possible comparative static predictions

S ↑

S ↓

Comparative Statics Table

S unchanged

(too confusing – use graphs)

(? - ambiguous change)

D ↑

P ↑ Q ↑

P ↓ Q ↑

P? Q ↑

P ↑ Q ↑

P Q

P ↑ Q ↑

P ↑ Q ↑

P ↑ Q ↓

P↑ Q ?

D unchanged

P Q

P ↓ Q ↑

P ↓ Q ↑

P Q

P Q

P Q

P Q

P ↑ Q ↓

P ↑ Q ↓

D ↓

P ↓ Q ↓

P ↓ Q ↑

P ↓ Q ?

P ↓ Q ↓

P Q

P ↓ Q ↓

P ↓ Q ↓

P ↑ Q ↓

P ? Q ↓

Explaining Markets with Tracks

• If P↑Q↑ , what kind of animal is it? D or S?

Which way is it going?

• If P↓Q↓, explain.

• If P↓Q↑, explain.

• If P↑Q↓, explain.

• Listening to market information on movements of

P and Q, help explain what is the primary influence on the market, D or S.

• NPR examples: Mad Cow and Tuition

The Invisible Hand

• Adam Smith summarized the remarkable coordination that results even as people follow their own self-interest. He called in the ¨ Invisible Hand ¨.

• As we saw in the Aplia experiment, consumer simply try to maximise their utility (TNB or gain) and producers try and maximize their profit (TNB or gain).

• Market prices are

– signals for resource allocation

– coordinate consumer and producer behavior

– incentives for buyers and sellers (MC for buyers and MB for sellers)

– Ration scarce goods and services

– Provide information about scarcity and value

• Prices help markets allocate resources more efficiently. Markets are efficient when

– They produce what consumers want or most highly value, and

– Produce those goods and services at least possible cost

– In Aplia, we saw the total gain increased as we moved to the equilibrium prices and quantities.

– We will explore the implications of this remarkable human creation as we proceed through the course.