Foster Care in Egypt: a Study of Policies, laws and Practices

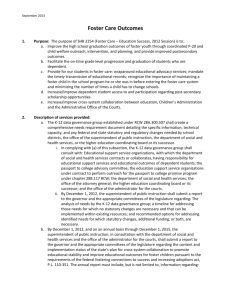

advertisement