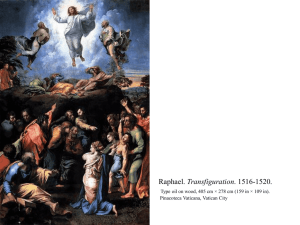

Figure 21-20

advertisement

Chapter 21 The Rise of Modernism: Art of the Later 19th Century Quiz question for next Tuesday Modernism and Realism 15 minutes: Outline the key ideas of “Modernism,” “Realism,” and the “Avant-garde,” and show how they can be SEEN in the form and content of two artworks – the Crystal Palace and either one photograph or one painting. NOTE: Make specific references to lecture, to Gardner’s Art through the Ages, and to the video, “A Fresh View: Impressionism and PostImpressionism.” Show that you can integrate and apply the three sources of information to works of art. Industrialization of Europe and U.S. about 1850 THOMAS EAKINS (American, 1844-1916) The Gross Clinic, 1875, oil on canvas, 8’ x 6’ 6”. Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. Empiricism, Positivism, faith in science (Enlightenment reason). Eadweard Muybridge (British-American 1830–1904), Horse Galloping, 1878. Collotype print. http://americanhistory.si.edu/ muybridge/img/gifs/i_0_01_ani .gif Eadweard Muybridge, ”Walking and turning around rapidly with a satchel in one hand, a cane in the other” Animal Locomotion Plate 49, 1887, Collotype Animal Locomotion is a series of 100 motion studies Muybridge made at the University of Pennsylvania between 1884 and 1887. Gustave Courbet (French, 1819-1877) Self-Portrait, c. 1845 A father of the avant-garde, Courbet combined the Romantic view of the artist as lone individual against middle class (bourgeois) values with the empiricism of the Positivists. GUSTAVE COURBET, The Stone Breakers, 1849. Oil on canvas, 5’ 3” x 8’ 6”. Formerly at Gemäldegalerie, Dresden (destroyed in 1945). Gustave Courbet is considered a father of avant-garde modernism. “Show me an angel and I’ll paint one.” William Bouguereau (French academic artist, 1825-1905) (left) Mother and Children, The Rest, 1879 ; (right) Home From the Harvest, 1878 Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans 1849-1850, oil on canvas, 10' 3’ x 21' 9" Musee d'Orsay, Paris Thomas Couture (French academic artist, 1815-79), Romans of the Decadence, 1847 Courbet, Burial at Ornans, 1849 compare with Thomas Couture, Romans of the Decadence, 1847 “I have studied, outside of any system and without prejudice, the art of the ancients and of the Moderns. I no more wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intuition to attain the trivial goal of art for art's sake. No! I simply wanted to draw forth from a complete acquaintance with tradition the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality" "To know in order to be able to create, that was my idea. To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my epoch, according to my own estimation: to be not only a painter, but a man as well: in short, to create living art - this is my goal.“ Gustave Courbet, statement for Pavilion of Realism, 1855 (left) Destruction of Paris following the Franco-Prussian war, siege of Paris, and (right) the Commune 1871, Communards shot by firing squad of French soldiers in the streets of Paris Courbet, the Communard, and the destruction of the Vendome column, symbol of Napoleonic (French) imperialism "Inasmuch as the Vendôme column is a monument devoid of all artistic value, tending to perpetuate by its expression the ideas of war and conquest of the past imperial dynasty, which are reproved by a republican nation's sentiment, citizen Courbet expresses the wish that the National Defense government will authorise him to disassemble this column.“ – Courbet ÉDOUARD MANET, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863, oil on canvas, 7’ x 8’10, ” Musée d’Orsay, Paris. ADOLPHE-WILLIAM BOUGUEREAU, Nymphs and Satyr, 1873. Oil on canvas, approx. 8’ 6” high. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. ÉDOUARD MANET, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 4’ 3” x 6’ 3”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Figure 21-26 ÉDOUARD MANET, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882. Oil on canvas, approx. 3’ 1” x 4’ 3”. Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London. Figure 21-20 CLAUDE MONET, Impression: Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 1’ 7 1/2” x 2’ 1 1/2”. Musée Marmottan, Paris. Figure 21-21 CLAUDE MONET, Saint-Lazare Train Station, 1877. Oil on canvas, 2’ 5 3/4” x 3’ 5”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Figure 21-22 GUSTAVE CAILLEBOTTE, Paris: A Rainy Day, 1877. Oil on canvas, approx. 6’ 9” x 9’ 9”. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Worcester Fund. Figure 21-23 CAMILLE PISSARRO, La Place du Théâtre Français, 1898. Oil on canvas, 2’ 4 1/2” x 3’ 1/2”. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles (the Mr. and Mrs. George Gard De Sylva Collection). Figure 21-24 HIPPOLYTE JOUVIN, The Pont Neuf, Paris, ca. 1860–1865. Albumen stereograph. Figure 21-25 PIERRE-AUGUSTE RENOIR, Le Moulin de la Galette, 1876. Oil on canvas, approx. 4’ 3” x 5’ 8”. Louvre, Paris. Figure 21-27 EDGAR DEGAS, Ballet Rehearsal, 1874. Oil on canvas, 1’ 11” x 2’ 9”. Glasgow Museum, Glasgow (The Burrell Collection). Figure 21-28 BERTHE MORISOT, Villa at the Seaside, 1874. Oil on canvas, approx. 1’ 7 3/4” x 2’ 1/8". Norton Simon Art Foundation, Los Angeles. Figure 21-29 CLAUDE MONET, Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (in Sun), 1894. Oil on canvas, 3’ 3 1/4” x 2’ 1 7/8”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Theodore M. Davis Collection, bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915). Figure 21-30 EDGAR DEGAS, The Tub, 1886. Pastel, 1’ 11 1/2” x 2’ 8 3/8”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. The Beginning of Impressionism • • Examine the Impressionists’ interest in sensation, impermanence, and the “fleeting moment” as it was expressed in their art. Understand the importance of light, color theory, and relevant scientific experiments. Japonisme and Later Impressionism • Examine issues of other Impressionist, such as the influence of the Japanese print and concerns with formal elements. Figure 21-31 MARY CASSATT, The Bath, ca. 1892. Oil on canvas, 3’ 3” x 2’ 2”. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (Robert A. Walker Fund). Figure 21-32 HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC, At the Moulin Rouge, 1892–1895. Oil on canvas, approx. 4’ x 4’ 7”. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection). Figure 21-33 JAMES ABBOTT MCNEILL WHISTLER, Nocturne in Black and Gold (The Falling Rocket), ca. 1875. Oil on panel, 1’ 11 5/8” x 1’ 6 1/2”. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit (gift of 21.5 Post-Impressionism • • • Understand the differences in emotional expression and subject choices between the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists. Understand the Post-Impressionist experimentation with form and color. Recognize the individuality of the Post-Impressionist artists and the styles each one developed. Emotion and the Impressionists • Understand emotional expression and subject choices in PostImpressionist art. Figure 21-34 VINCENT VAN GOGH, The Night Café, 1888. Oil on canvas, approx. 2’ 4 1/2” x 3’. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (bequest of Stephen Carlton Clark, B.A., 1903). Figure 21-35 VINCENT VAN GOGH, Starry Night, 1889. Oil on canvas, approx. 2’ 5” x 3’ 1/4”. Museum of Modern Art, New York (acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest). Figure 21-36 PAUL GAUGUIN, The Vision after the Sermon or Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1888. Oil on canvas, 2’ 4 3/4” x 3’ 1/2”. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. Post-Impressionist Experimentation • Understand the Post-Impressionist experimentation with form and color. Figure 21-37 PAUL GAUGUIN, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, 1897. Oil on canvas, 4’ 6 13/ 16” x 12’ 3”. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Tompkins Collection). Figure 21-38 GEORGES SEURAT, detail of A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884– 1886. Figure 21-39 GEORGES SEURAT, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884–1886. Oil on canvas, approx. 6’ 9” ´ 10’. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, 1926). Post-Impressionist Form • Examine the extraordinary art of Cezanne and his interest in form, paving the way for Cubism. Figure 21-40 PAUL CÉZANNE, Mont Sainte-Victoire, 1902–1904. Oil on canvas, 2’ 3 1/2” x 2’ 11 1/4”. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (The George W. Elkins Collection). Figure 21-41 PAUL CÉZANNE, The Basket of Apples, ca. 1895. Oil on canvas, 2’ 3/8” x 2’ 7”. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection, 1926). Figure 21-42 PIERRE PUVIS DE CHAVANNES, The Sacred Grove, 1884. Oil on canvas, 2’ 11 1/2” x 6’ 10”. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (Potter Palmer Collection). Figure 21-43 GUSTAVE MOREAU, Jupiter and Semele, ca. 1875. Oil on canvas, approx. 7’ x 3’ 4”. Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris. Figure 21-44 ODILON REDON, The Cyclops, 1898. Oil on canvas, 2’ 1” x 1’ 8”. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands. 21.6 Symbolism • • Examine the issues of imagination, fantasy, and formal changes in the art of the Symbolists. Understand the expression of “modern psychic life” in the art of the Symbolists. Figure 21-45 HENRI ROUSSEAU, The Sleeping Gypsy, 1897. Oil on canvas, 4’ 3” x 6’ 7”. Museum of Modern Art, New York (gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim). Figure 21-46 EDVARD MUNCH, The Cry, 1893. Oil, pastel, and casein on cardboard, 2’ 11 3/4” x 2’ 5”. National Gallery, Oslo. 21.7 Sculpture in the Later 19th Century • • • Examine the issues of realism and expression related to sculpture in the later 19th century. Understand the selection of contemporary subject matter by sculptors. Recognize representative sculptors and works of the later 19th century. Sculpture: Realist and Expressive • Examine issues of realism, expression and subject matter in sculpture of the later 19th century. Figure 21-47 JEAN-BAPTISTE CARPEAUX, Ugolino and His Children, 1865–1867. Marble, 6’ 5” high. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation, Inc. and the Figure 21-48 AUGUSTUS SAINT-GAUDENS, Adams Memorial, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, 1891. Bronze, 5’ 10” high. Figure 21-49 AUGUSTE RODIN, Walking Man, 1905, cast 1962. Bronze, 6’ 11 3/4” high. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington (gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966). Figure 21-50 AUGUSTE RODIN, Burghers of Calais, 1884–1889, cast ca. 1953– 1959. Bronze, 6’ 10 1/2” high, 7’ 11” long, 6’ 6” deep. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington (gift of Joseph H. 21.8 The Arts and Crafts Movement • • • • Examine the ideas of Ruskin and Morris in shaping the Arts and Crafts Movement. Understand the interest in aesthetic functional objects in the Arts and Crafts Movement. Examine the preference for high-quality artisanship and honest labor. Examine the preferred nature forms of Art Nouveau in art and architecture. Objects and Décor of the Arts & Crafts • Understand the interest in aesthetic functional objects and the preference for high-quality artisanship and honest labor. Figure 21-51 WILLIAM MORRIS, Green Dining Room, 1867. Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Figure 21-52 CHARLES RENNIE MACKINTOSH, reconstruction (1992–1995) of Ladies’ Luncheon Room, Ingram Street Tea Room, Glasgow, Scotland, 1900–1912. Glasgow Museum, Glasgow. Figure 21-53 VICTOR HORTA, staircase in the Van Eetvelde House, Brussels, 1895. Figure 21-54 AUBREY BEARDSLEY, The Peacock Skirt, 1894. Pen-and-ink illustration for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. Nature in Art Nouveau Architecture • Examine the organic nature forms in Art Nouveau architecture. Figure 21-55 ANTONIO GAUDI, Casa Milá, Barcelona, 1907. Figure 21-56 GUSTAV KLIMT, The Kiss, 1907–1908. Oil on canvas, 5’ 10 3/4” x 5’ 10 3/4”. Austrian Gallery, Vienna. 21.7 Architecture in the Later 19th Century • • • • Understand the new technology and changing needs of urban society and their effects on architecture. Examine new materials use in architecture and the forms made possible as a result. Understand how architects were able to think differently about space as a result of new technology and materials. Examine the remarkable work and theories of Louis Sullivan. New Technology and Materials • Understand new technology, changing needs of urban society, and new materials in architecture. Figure 21-57 ALEXANDREGUSTAVE EIFFEL, Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1889 (photo: 1889–1890). Wrought iron, 984’ high. Figure 21-58 HENRY HOBSON RICHARDSON, Marshall Field wholesale store (demolished), The Architecture of Louis Sullivan • Understand the issues of space and decoration in the remarkable work and theories of Louis Sullivan. Figure 21-59 LOUIS SULLIVAN, Guaranty (Prudential) Building, Buffalo, 1894–1896. Figure 21-60 LOUIS SULLIVAN, Carson, Pirie, Scott Building, Chicago, 1899– 1904. Figure 21-61 RICHARD MORRIS HUNT, The Breakers, Newport, Rhode Island, 1892. Figure 21-62 LOUIS COMFORT TIFFANY, Lotus table lamp, ca. 1905. Leaded Favrile glass, mosaic, and bronze, 2’ 10 1/2” high. Private collection. Discussion Questions In what ways did the Modernist art of the later 19th century break from the past? How did Modernist artists call attention to the ‘facts’ of art making? Why did the public find the subjects, forms, and techniques of the Impressionists shocking? What would you consider the most important breakthrough in architecture?