Operations Improvement

advertisement

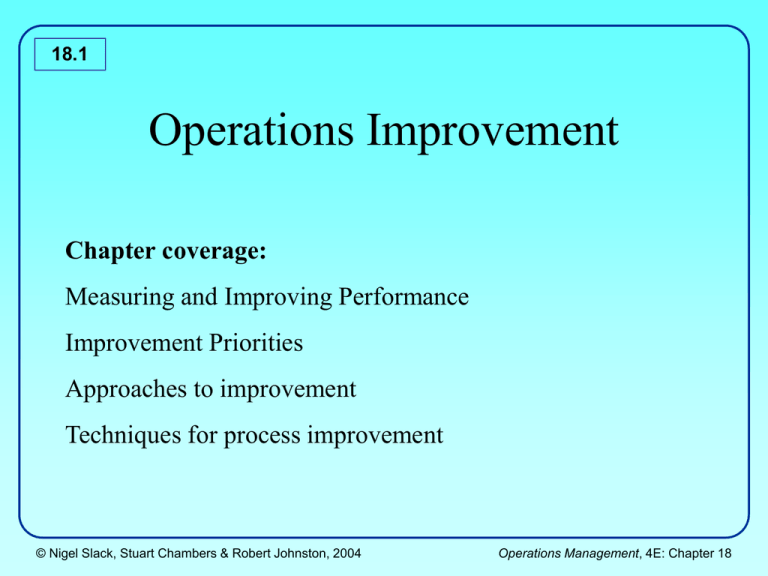

18.1 Operations Improvement Chapter coverage: Measuring and Improving Performance Improvement Priorities Approaches to improvement Techniques for process improvement © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.2 Measuring and Improving Performance 1) Performance measurement – Performance: the degree to which the operations fulfils performance objectives at any point in time, in order to satisfy customers. – Performance objectives: quality, speed, dependability, flexibility and cost – Can represented on a Polar diagram. © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.3 Polar diagram - How operations can measure their performance Cost Speed Cost Dependability Quality Flexibility Speed Dependability Quality Flexibility Market requirements and operations performance change over time Performance of the operation © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Requirements of the market Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.4 2) Performance standards – – After an operation has measured its performance, it needs to make a judgement as to whether its performance is good, bad or indifferent. Four ways of comparing current performance to some kind of performance standard: 1. 2. 3. 4. Historical Standard Target performance standard Competitor performance standards Absolute performance standards © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.5 1. Historical standards – – – Comparison against previous performance Judges if operation is getting better or not over time. No indication if performance is satisfactory 2. Target performance standards – – – Target set randomly to reflect some level of performance. Must be appropriate and reasonable Example: Budget (quarterly review) © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.6 3. Competitor performance standards – – – Comparison against one or more of the organizations competitors. Relates performance directly to its competitive ability Good for strategic performance improvement 4. Absolute performance standards – – Target is a theoretical limit. Example: ‘zero defects’, or ‘zero LTI” © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.7 Measuring and Improving Performance 3) Benchmarking – Compares operation with those of other companies. – Process of learning from others – Widely adopted because: a) The problems faced in managing their processes are most likely similar to other operations managers elsewhere. b) There is probably another operation somewhere that has developed a better way of doing things © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 Measuring and Improving Performance 18.8 – Some objectives: • • • To judge how well an operation is doing To set realistic performance standards. To search for new idea and practices which can be adopted © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.9 Measuring and Improving Performance – Examples of benchmarking include: • A dishwasher manufacturer comparing the energy efficiency of its own products against its competitors • An online retailer of computer accessories comparing the way it organizes its warehouse and delivery with an online retailer of books and DVDs • A hotel chain comparing the room cleaning times in all its hotels • A chemical company comparing its transportation and distribution practices with a specialist logistics company. © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 Measuring and Improving Performance 18.10 – Types of benchmarking (not mutually exclusive): • Internal benchmarking – comparison made within the same organization. – Example: a large motor vehicle manufacturer with several factories might choose to benchmark each factory against the others. • External benchmarking – comparison between an operation and other operations which are not part of same organization. © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 Measuring and Improving Performance 18.11 • • • • Non-competitive benchmarking – comparison against external organizations which do not compete directly in the same markets. Competitive benchmarking – comparison between competitors. Performance benchmarking – comparison between the levels of achieved performance in different operations. Practice benchmarking – comparison of the way of doing things. – Example: comparison of SOP for controlling stock levels by other department stores. © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.12 Improvement Priorities Major influences on deciding improvement priorities: – The needs and preference of customers – The performance and activities of competitors 1. Judging importance to customers 2. Judging performance against competitors 3. The importance-performance matrix © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.13 9 Point Importance Scale Judging importance to customers For this product group does this performance objective ...... ORDER WINNING OBJECTIVES 1 - Provide a crucial advantage with customers 2 - Provide an important advantage with most customers 3 - Provide a useful advantage with most customers 4 - Need to be up to good industry standard QUALIFYING OBJECTIVES 5 - Need to be around median industry standard 6 - Need to be within close range of the rest of the industry LESS IMPORTANT OBJECTIVES 7 - Not usually important but could become more so in future 8 - Very rarely rate as being important 9 - Never come into consideration © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.14 9 Point Performance Scale Judging performance against competitors For this product group is achieved performance ........ BETTER THAN COMPETITORS SAME AS COMPETITORS WORSE THAN COMPETITORS 1 - Consistently considerably better than our nearest competitor 2 - Consistently clearly better than our nearest competitor 3 - Consistently marginally better than our nearest competitor 4 - Often marginally better than most competitors 5 - About the same as most competitors 6 - Often close to main competitors 7 - Usually marginally worse than main competitors 8 - Usually worse than most competitors 9 - Consistently worse than most competitors © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 GOOD 18.15 1 better than EXCESS ? 2 APPROPRIATE COMPETITORS AGAINST PERFORMANCE 3 4 same as IMPROVE 6 7 worse than BAD 5 URGENT ACTION 8 9 9 8 7 less important 6 5 4 3 2 1 order winning qualifying IMPORTANCE LOW © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 FOR CUSTOMERS HIGH Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.16 Approaches to improvement 1.Breakthrough improvement • • Innovation based improvement Example: introduction of a new, more efficient machine in a factory 2.Continuous improvement - Kaizen • • • Smaller incremental improvement steps Example: modifying the way a component is fixed to an equipment to reduce change over time. Rate of improvement is not important but the momentum is. © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 (a) ‘Breakthrough’ improvement, (b) ‘continuous’ improvement and (c) combined improvement patterns Planned “breakthrough” improvements Actual improvement pattern Continuous improvement Time (b) Performance (a) Performance Performance 18.17 Time Combined “breakthrough” and continuous improvement Time (c) © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.18 3.The difference between breakthrough and continuous improvement Innovation... Short-term, dramatic Big steps Intermittent Abrupt, volatile Few ‘champions’ Individual ideas & effort New inventions/theories Concentrated ‘all eggs in 1 basket’ Large investment Technology Results for profit ...Kaizen Effect Pace Timeframe Change Involvement Approach Stimulus Risks Practical req. Effort orientation Evaluation criteria © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Long-term, undramatic Small steps Continuous, incremental Gradual and consistent Everyone Group efforts Conventional know-how Spread Little investment People Process Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.19 4. Improvement cycle models • • • Improvement can be represented by a never-ending process of repeatedly questioning and re-questioning the detailed working of a process activity This repeated and cyclical nature of continuous improvement is usually summarized by improvement cycles Examples of improvement cycles: – PDCA cycle – DMAIC cycle © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.20 Define Plan Do Measure Control Act Check Improve (a) Analyze (b) (a) The plan-do-check-act (b) The define-measure-analyze-improve-control © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.21 Performance PDCA Cycle repeated to create continuous improvement Plan Act Do Check “Continuous” improvement Time © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.22 The common techniques for process improvement Input/output analysis Flow charts Scatter diagrams x Input Out put x x x x x x x x x Cause-effect diagrams Pareto diagrams x Why-why analysis Why? Why? Why? © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.23 Cause-and-effect diagram • Also called Fishbone diagram or Ishikawa diagram. • Used to identify root cause of a problem or potential solution for an objective. • Encourages team work. Cause Cause Cause Effect Cause Cause © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.24 Cause-and-effect diagram Construct a cause-and-effect diagram to identify the causes of poor gas mileage of your car. Step 1: – Identify the effect – Can be positive (objective) or negative (problem) © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.25 Cause-and-effect diagram Step 2: – Fill in the effect box and draw the spine Step 3: – Identify main categories Man Machinery POOR GAS MILEAGE Environment Materials Method © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.26 Cause-and-effect diagram Step 4: – Identify causes influencing the effect Man Machinery Use wrong gear POOR GAS MILEAGE Environment Wrong octane gas Materials Method © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.27 Cause-and-effect diagram Step 5: – Add detailed level Poor hearing Can’t hear Man engine Machinery Radio too loud Use wrong gear POOR GAS MILEAGE Environment No owner’s manual Don’t know recommended octane Wrong octane gas Materials Method © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.28 Cause-and-effect diagram Poor hearing Can’t hear Man engine Machinery Radio too loud Use wrong gear POOR GAS MILEAGE Environment No owner’s manual Don’t know recommended octane Wrong octane gas Materials Method © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.29 Cause-and-effect diagram Step 6: – Analyse the diagram • Select which cause to take action on. © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18 18.30 The End © Nigel Slack, Stuart Chambers & Robert Johnston, 2004 Operations Management, 4E: Chapter 18