Acts of Parliament

advertisement

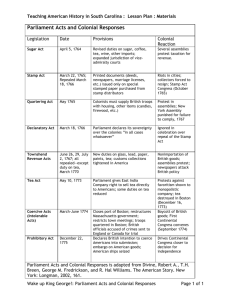

Parliament Acts and Colonial Responses Legislation Sugar Act Stamp Act Quartering Act Declaratory Act Townshend Revenue Acts Tea Act Coercive Acts (Intolerable Acts) Prohibitory Act Date April 5, 1764 March 22, 1765; repealed March 18, 1766 May 1765 March 18, 1766 June 26, 29, July 2, 1767; all repealed except duty on tea, March 1770 May 10, 1773 March – June 1774 December 22, 1775 Provisions Colonial Reaction Revised duties on sugar, coffee, tea, wine, other imports; expanded jurisdiction of viceadmiralty courts Several assemblies protest taxation for revenue Printed documents (deeds, newspapers, marriage licenses, etc.) issued only on special stamped paper purchased from stamp distributors Riots in cities; collectors forced to resign; Stamp Act Congress (October 1765) Colonists must supply British troops with housing and other items (candles, firewood, etc.) Parliament declares its sovereignty over the colonies “in all cases whatsoever” Protest in assemblies; New York Assembly punished for failure to comply, 1767 Ignored in celebration over repeal of the Stamp Act New duties on glass, lead, paper, paints, tea; customs collections tightened in America Non-importation of British goods; assemblies protest; newspapers attack British policy Parliament gives East India Company the right to sell tea directly to Americans; some duties on tea reduced Closes port of Boston; restructures Massachusetts government; restricts town meetings; troops quartered in Boston; British officials accused of crimes sent to England or Canada for trial Protests against favoritism shown to monopolistic company; tea destroyed in Boston (December 16, 1773) Declares British intention to coerce Americans into submission; embargo on American goods; American ships seized Boycott of British goods; First Continental Congress convenes (September 1774) Drives Continental Congress closer to decision for independence Parliament Acts and Colonial Responses is adapted from Divine, Robert A., T.H. Breen, George M. Fredrickson, and R. Hal Williams. The American Story. New York; Longman, 2002, 161. Acts of Parliament Stamp Act, (1765), in U.S. colonial history, was the first British parliamentary attempt to raise revenue through direct taxation of all colonial commercial and legal papers, newspapers, pamphlets, cards, almanacs, and dice. The devastating effect of Pontiac’s War (1763–64) on colonial frontier settlements added to the enormous new defense burdens resulting from Great Britain’s victory (1763) in the French and Indian War. The British chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir George Grenville, hoped to meet at least half of these costs by the combined revenues of the Sugar Act (1764) and the Stamp Act, a common revenue device in England. Completely unexpected was the avalanche of protest from the colonists, who effectively nullified the Stamp Act by outright refusal to use the stamps as well as by riots, stamp burning, and intimidation of colonial stamp distributors. Colonists passionately upheld their rights as Englishmen to be taxed only by their own consent through their own representative assemblies, as had been the practice for a century and a half. In addition to nonimportation agreements among colonial merchants, the Stamp Act Congress was convened in New York (October 1765) by moderate representatives of nine colonies to frame resolutions of “rights and grievances” and to petition the king and Parliament for repeal of the objectionable measures. Bowing chiefly to pressure (in the form of a flood of petitions to repeal) from British merchants and manufacturers whose colonial exports had been curtailed, Parliament, largely against the wishes of the House of Lords, repealed the act in early 1766. Simultaneously, however, Parliament issued the Declaratory Act, which reasserted its right of direct taxation anywhere within the empire, “in all cases whatsoever.” The protest throughout the colonies against the Stamp Act contributed much to the spirit and organization of unity that was a necessary prelude to the struggle for independence a decade later. The Intolerable Acts, also called Coercive Acts, in U.S. colonial history, were four punitive measures enacted by the British Parliament in retaliation for acts of colonial defiance, together with the Quebec Act establishing a new administration for the territory ceded to Britain after the French and Indian War (1754–63). Angered by the Boston Tea Party (1773), the British government passed the Boston Port Bill, closing that city’s harbor until restitution was made for the destroyed tea. Second, the Massachusetts Government Act abrogated the colony’s charter of 1691, reducing it to the level of a crown colony, substituting a military government under General Thomas Gage, and forbidding town meetings without approval. The third, the Administration of Justice Act, was aimed at protecting British officials charged with capital offenses during law enforcement by allowing them to go to England or another colony for trial. The fourth Coercive Act included new arrangements for housing British troops in occupied American dwellings, thus reviving the indignation that surrounded the earlier Quartering Act, which had been allowed to expire in 1770. The Quebec Act, under consideration since 1773, removed all the territory and fur trade between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers from possible colonial jurisdiction and awarded it to the province of Quebec. By establishing French civil law and the Roman Catholic religion in the coveted area, Britain acted liberally toward Quebec’s settlers but raised the specter of popery before the mainly Protestant colonies to Canada’s south. In late 1775, Parliamentary leaders looked back over the preceding months and noted the total disintegration of the relationship between the mother country and the 13 American colonies — Lexington, Concord, Bunker Hill, the seizure of Ticonderoga and an invasion of Canada then in progress were stark evidence of the rupture. Retaliation came in the form of the American Prohibitory Act that was designed to strike at the economic viability of the errant colonies. The law first stated its rationale for action, noting the following: the colonies were staging a rebellion against the authority of king and Parliament they had raised an army and engaged his majesty's soldiers they had illegally taken over the powers of government they had stopped trade with the mother country. Given those circumstances, Parliament felt compelled to prohibit all British trade with the American colonies. Further, all American ships and cargoes were to be treated as if they belonged to an enemy power and were subject to seizure; if adjudged a lawful prize by an admiralty court, the ships and cargoes were to be sold and the proceeds distributed among the capturing ship’s officers and crew. This measure served as a declaration of economic warfare and did not go unnoticed in the colonies. Congress and the individual states reacted by issuing letters of marque, which authorized individual American ship owners to seize British ships in a practice known as privateering.