Chapter No. 8

advertisement

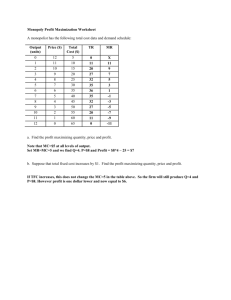

22 Pure Monopoly 22-1 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Learning objectives • In this chapter students will learn: A. The characteristics of pure monopoly. B. How a pure monopoly sets its profit-maximizing output and price. C. About the economic effects of monopoly. D. Why a monopolist might prefer to charge different prices in different markets. 22-2 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Pure Monopoly: An Introduction Definition: Pure monopoly exists when a single firm is the sole producer of a product for which there are no close substitutes. • There are a number of products where the producers have a substantial amount of monopoly power and are called “near” monopolies. • There are several characteristics that distinguish pure monopoly: 1. There is a single seller so the firm and industry are synonymous (the same). 2. There are no close substitutes for the firm’s product. 3. The firm is a “price maker” that is, the firm has considerable control over the price because it can control the quantity supplied. 4. Entry into the industry by other firms is blocked. 5. A monopolist may or may not engage in nonprice competition. Depending on the nature of its product, a monopolist may advertise to increase demand. 22-3 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Barriers to Entry Limiting Competition: 1. Economies of scale constitute one major barrier. This occurs where the lowest unit costs and, therefore, lowest unit prices for consumers depend on the existence of a small number of large firms or, in the case of a pure monopoly, only one firm. Because a very large firm with a large market share is most efficient, new firms cannot afford to start up in industries with economies of scale 2. Public utilities are often natural monopolies because they have economies of scale in the extreme case where one firm is most efficient in satisfying existing demand (two or more firms will lead to higher ATC). • Government usually gives one firm the right to operate a public utility industry in exchange for government regulation of its power. 22-4 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Average Total Cost THE NATURAL MONOPOLY CASE $20 15 10 If ATC declines over extended output, least-cost production is realized only if there is one producer - a natural monopoly 0 22-5 ATC 50 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 100 Quantity 200 • The explanation of why more than one firm would be inefficient involves the description of the maze of pipes or wires that would result if there were competition among water companies, electric utility companies, etc. 3. Legal barriers to entry into a monopolistic industry also exist in the form of patents and licenses. a) Patents grant the inventor the exclusive right to produce or license a product for twenty years; this exclusive right can earn profits for future research, which results in more patents and monopoly profits. b) Licenses are another form of entry barrier. Radio and TV stations are examples of government granting licenses where only one or a few firms are allowed to offer the service. 22-6 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies c) • • • • • Ownership or control of essential resources is another barrier to entry. International Nickel Co. of Canada (now called Inco) controlled about 90 percent of the world’s nickel reserves, and DeBeers of South Africa controls most of the world’s diamond supplies. Aluminum Co. of America (Alcoa) once controlled all basic sources of bauxite, the ore used in aluminum fabrication. Monopolists may use pricing or other strategic barriers such as selective price-cutting and advertising. Dentsply, manufacturer of false teeth, controlled about 70 percent of the market. In 2005 Dentsply was found to have illegally prevented distributors from carrying competing brands. Microsoft charged higher prices for its Windows operating system to computer manufacturers featuring Netscape Navigator instead of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer. U.S. courts ruled 22-7 this action illegal. Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • Monopoly demand is the industry (market) demand and is therefore downward sloping. • Our analysis of monopoly demand makes three assumptions: 1. The monopoly is secured by patents, economies of scale, or resource ownership. 2. The firm is not regulated by any unit of government. 3. The firm is a single-price monopolist; it charges the same price for all units of output. • • Price will exceed marginal revenue because the monopolist must lower the price to sell the additional unit. The added revenue (MR) will be the price of the last unit less the sum of the price cuts which must be taken on all prior units of output. The marginal-revenue curve is below the demand curve, and when it becomes negative, the total-revenue curve turns downward as total-revenue falls. 22-8 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Price and Marginal Revenue Marginal Revenue is Less Than Price • A Monopolist is Selling 3 Units at $142 • To Sell More (4), $142 Price Must Be 132 Lowered to $132 122 • All Customers Must Pay the Same 112 Price 102 • TR Increases $132 92 Minus $30 (3x$10) Loss = $30 D Gain = $132 82 0 22-9 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 1 2 3 4 5 6 Price and Marginal Revenue Marginal Revenue is Less Than Price • A Monopolist is Selling 3 Units at $142 • To Sell More (4), $142 Price Must Be 132 Lowered to $132 122 • All Customers Must Pay the Same 112 Price 102 • TR Increases $132 92 Minus $30 (3x$10) 82 • $102 Becomes a Point on the MR Curve • Try Other Prices to Determine Other 0 MR Points Loss = $30 D Gain = $132 MR 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Constructed Marginal Revenue Curve Must Always Be Less Than the Price 22-10 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • The monopolist is a price maker. The firm controls output and price but is not free of market forces, since the combination of output and price that can be sold depends on demand. For example, Table 22.1 shows that at $162 only 1 unit will be sold, at $152 only 2 units will be sold, etc. • Price elasticity also plays a role in monopoly price setting. The total revenue test shows that the monopolist will avoid the inelastic segment of its demand schedule. As long as demand is elastic, total revenue will rise when the monopoly lowers its price, but this will not be true when demand becomes inelastic. At this point, total revenue falls as output expands, and since total costs rise with output, profits will decline as demand becomes inelastic. Therefore, the monopolist will expand output only in the elastic portion of its demand curve. 22-11 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • Output and Price Determination • Cost data is based on hiring resources in competitive markets, so the cost data of Chapters 20 and 21 can be used in this chapter as well. • The MR = MC rule will tell the monopolist where to find its profit-maximizing output level. The same result can be found by comparing total revenue and total costs incurred at each level of production. • The pure monopolist has no supply curve because there is no unique relationship between price and quantity supplied. The price and quantity supplied will always depend on location of the demand curve. 22-12 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Monopoly Revenue and Costs Revenue and Cost Data of a Pure Monopolist Cost Data Revenue Data (2) Price (1) Quantity (Average Of Output Revenue) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 $172 162 152 142 132 122 112 102 92 82 72 (3) Total Revenue (1) X (2) $0 ] 162 ] 304 ] 426 ] 528 ] 610 ] 672 ] 714 ] 736 ] 738 ] 720 (4) Marginal Revenue $162 142 122 102 82 62 42 22 2 -18 (5) (6) (7) (8) Average Total Cost Marginal Profit (+) Total Cost (1) X (5) Cost or Loss (-) $190.00 135.00 113.33 100.00 94.00 91.67 91.43 93.75 97.78 103.00 $100 ] 190 ] 270 ] 340 ] 400 ] 470 ] 550 ] 640 ] 750 ] 880 ] 1030 $90 80 70 60 70 80 90 110 130 150 $-100 -28 +34 +86 +128 +140 +122 +74 -14 -142 -310 Can you See Profit Maximization? 22-13 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Monopoly Revenue and Costs Demand, Marginal Revenue, and Total Revenue for a Pure Monopolist $200 Demand and Marginal Revenue Curves Elastic Inelastic Price 150 100 50 D MR 0 2 4 Total Revenue $750 8 10 12 Total-Revenue Curve 14 16 18 500 250 0 22-14 6 TR 2 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 Profit Maximization By A Pure Monopolist Price, Costs, and Revenue $200 175 MC 150 Pm=$122 125 100 75 Economic Profit ATC A=$94 D MR=MC 50 25 0 MR 1 2 3 4 5 6 Quantity 22-15 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 7 8 9 10 Loss Minimization Price, Costs, and Revenue By A Pure Monopolist MC A Pm ATC Loss AVC V D MR=MC MR 0 Qm Quantity 22-16 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • There are several misconceptions about monopoly prices. 1. Monopolist cannot charge the highest price it can get, because it will maximize profits where total revenue minus total cost is greatest. This depends on quantity sold as well as on price and will never be the highest price possible. 2. Total, not unit, profits is the goal of the monopolist. Once again, quantity must be considered as well as unit profit. 3. Unlike the purely competitive firm, the pure monopolist can continue to receive economic profits in the long run. Although losses can occur in a pure monopoly in the short run (P>AVC), the less-than-profitable monopolist will shutdown in the long run (P>ATC). 22-17 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Evaluation of the Economic Effects of a Monopoly • Price, output, and efficiency of resource allocation should be considered. • Monopolies will sell a smaller output and charge a higher price than would competitive producers selling in the same market, i.e., assuming similar costs. • Monopoly price will exceed marginal cost, because it exceeds marginal revenue and the monopolist produces where marginal revenue and marginal cost are equal. The monopolist charges the price that consumers will pay for that output level. • Allocative efficiency is not achieved because price (what product is worth to consumers) is above marginal cost (opportunity cost of product). Ideally, output should expand to a level where price = marginal revenue = marginal cost, but this will occur only under pure competitive conditions where price = marginal revenue. (See Figure 22.6) 22-18 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Economic Effects of Monopoly Price, Output, and Efficiency Pure Monopoly Purely Competitive Market S=MC MC Pm P=MC= Minimum ATC Pc b c Pc a D D MR Qc P = MC Qm Qc P > MC Pure Competition is Efficient. Monopoly Price is Greater Than MC And Is Therefore Inefficient 22-19 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • Productive efficiency is not achieved because the monopolist’s output is less than the output at which average total cost is minimum. • The efficiency (or deadweight) loss is also reflected in the sum of consumer and producer surplus equaling less than the maximum possible value. • Income distribution is more unequal than it would be under a more competitive situation. The effect of the monopoly power is to transfer income from the consumers to the business owners. This will result in a redistribution of income in favor of higher-income business owners, unless the buyers of monopoly products are wealthier than the monopoly owners. 22-20 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Assessment and policy options: • Although there are legitimate concerns of the effects of monopoly power on the economy, monopoly power is not widespread. While research and technology may strengthen monopoly power, overtime it is likely to destroy monopoly position. • When monopoly power is resulting in an adverse effect upon the economy, the government may choose to intervene on a case-by-case basis Price discrimination • occurs when a given product is sold at more than one price and the price differences are not based on cost differences. Price discrimination can take three forms: 1. Charging each customer in a single market the maximum price he or she is willing to pay. 2. Charging each customer one price for the first set of units purchased, and a lower price for subsequent units. 3. Charging one group of customers one price, and another group a different price. 22-21 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Conditions needed for successful price discrimination: 1. Monopoly power is needed with the ability to control output and price. 2. The firm must have the ability to segregate the market, to divide buyers into separate classes that have a different willingness or ability to pay for the product (usually based on differing elasticities of demand). 3. Buyers must be unable to resell the original product or service. Examples of price discrimination: 1. Airlines charge high fares to executive travelers (inelastic demand) than vacation travelers (elastic demand). 2. Electric utilities frequently segment their markets by end uses, such as lighting and heating. (Lack of substitutes for lighting makes this demand inelastic). 3. Long-distance phone service has higher rates during the day, when businesses must make their calls (inelastic demand), and lower rates at night and on week-ends, when less important calls are made. 22-22 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 4. Discount coupons are a form of price discrimination, allowing firms to offer a discount to price-sensitive customers. 5. International trade has examples of firms selling at different prices to customers in different countries. Regulated Monopoly • This occurs where a natural monopoly or economies of scale make one firm desirable. • As a result of changes in technology and deregulation in the local telephone and the electricity-providers industry, some states are allowing new entrants to compete in previously regulated markets. • In those markets that are still regulated, a regulatory commission may attempt to establish the legal price for the monopolist that is equal to marginal cost at the quantity of output chosen. This is called the “socially optimal price. 22-23 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Regulated Monopoly Dilemma of Regulation Price and Costs (Dollars) Monopoly Price Pm Fair-Return Price f Pf a Socially Optimal Price ATC Pr r MR 0 Qm Quantity 22-24 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies MC D b Qf Qr • However, setting price equal to marginal cost may cause losses, because public utilities must invest in enough fixed plant to handle peak loads. Much of this fixed plant goes unused most of the time, and a price = marginal cost would be below average total cost. Regulators often choose a price equal to average cost rather than marginal cost, so that the monopoly firm can achieve a “fair return” and avoid losses. (Recall that average-total cost includes an allowance for a normal or “fair” profit) • The dilemma for regulators is whether to choose a socially optimal price, where P = MC, or a fair-return price, where P = AC. P = MC is most efficient but may result in losses for the monopoly firm, and government then would have to subsidize the firm for it to survive. P = AC does not achieve allocative efficiency, but does insure a fair return (normal profit) for the firm. 22-25 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies • LAST WORD: De Beers’ Diamonds: Are Monopolies Forever? • De Beers Consolidated Mines of South Africa has been one of the world’s strongest and most enduring monopolies. It produces about 45 percent of all rough-cut diamonds in the world and buys for resale many of the diamonds produced elsewhere, for a total of about 55 percent of the world’s diamonds. • Its behavior and results fit the monopoly model portrayed in Figure 22.4. It sells a limited quantity of diamonds that will yield an “appropriate” monopoly price. • The “appropriate” price is well over production costs and has earned substantial economic profits. • How has De Beers controlled the production of mines it doesn’t own? 1. It convinces producers that “single-channel” monopoly marketing is in their best interests 22-26 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 2. Mines that don’t use De Beers may find the market flooded from De Beers stockpiles of the particular kind of diamond they produce, which causes price declines and loss of profits. 3. Finally, De Beers purchases and stockpiles diamonds produced by independents Threats and problems face De Beers’ monopoly power. 1. New diamond discoveries have resulted in more diamonds outside their control. 2. Russia, which has been a part of De Beers’ monopoly, has agreed to sell progressively larger quantities directly to the world market rather than through De Beers. • In mid-2000, De Beers abandoned its attempt to control the supply of diamonds. • The company is transforming itself into a company that sells “premium” diamonds and luxury goods under the De Beers label. • De Beers plans to reduce its stockpile of diamonds and increase the demand for diamonds through advertising. 22-27 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Key Terms • • • • • • • • • pure monopoly barriers to entry simultaneous consumption network effects X-inefficiency rent-seeking behavior price discrimination socially optimal price fair-return price 22-28 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies Next Chapter Preview… Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly 22-29 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies 22-30 Copyright 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies