Psychology of Injured Athlete - University of Minnesota Duluth

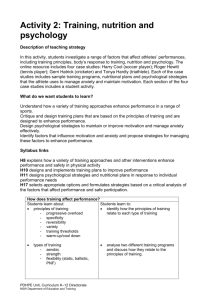

advertisement

Psychology of Injured Athlete Dr. Duane Millslagle Associate Professor University of Minnesota Duluth Outline Psychological Perspective of Athletic Injury Patient-Practitioner Interaction in Sport Injury Rehabilitation Specialized psychological interventions in Sport Injury Rehabilitation The Bio-psychological perspective of pain Integrated Rehabilitation Model:A Team Approach Psychological Perspective of Athletic Injury Assessing and Monitoring Injuries The Paradox of Injuries: Unexpected Positive Consequences Personality Correlates of Psychological Processes During Injury Rehab Stage Model Versus Cognitive Appraisal Model Macrotrauma & Microtrauma: Different Psychological Reactions Assessing & Monitoring Injuries Identify moderating variables that relate to athletic injury Compare injured athletes to non-injured athletes Use of psychological inventories as the primary tool Severity of the injury Effects of psychological factors on injuries Effects of Psychological Factors on Injuries Area of life stress Dealing with stress may affect the athlete likelihood to become injured. Life stress results from both within and outside the athletic contest Level of life stress is associated with the injury A proactive approach Periodic monitoring to assess one’s level of life stress is necessary. Established psychological inventories Interviews With athletes who experience distress A need to reduce the stress to facilitate restoration of psychological and physiological states Research Evidence Elite female gymnasts (Kerr & Minden, 1988) Noncontact athletes (Hardy & Riehl, 1988) Football players (Blackwell & McCullagh, 1990). Adolescent sport injuries (Smith, Smoll, & Ptacek, 1990) Athletic Injury Being sport related Results in a player’s inability to participate on day after injury Requires medical attention Injury Frequency Injury Rate = Definition of Injury Population-at-risk Severity of Injury No universal definition exists Based on AMA Standards Nomenclature of Injuries (1968) Depends on the time-loss Depends on functional consequences of participation or not participation Psychological tests Profile of Mood States (POMs)-McNair, 1971 Eating Disorders Inventory-2(EDI-2)-Dean, et al. 1990 Health Attribution Test(HAT)-Lawlis & Lawlis, 1990 Coping Resources Inventory(CRI)-Hammer & Marting, 1988 Life Experiences Survey-Athletes(TESS)Morrow & Hardy, 1990 Paradox of Injuries “The injury made me a lot more mature. I have a better grasp of reality in life……I’m so much stronger emotionally. (Lieber, 1991, p.44) Are there ways to facilitate these positive consequences with athlete injuries? Adversity & Stress General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) by Selye (1974) Alarm- injured person resists any additional stressors Exhaustion-additional stressors cause injured person to succumb to stress Adaptation phase-injured become stronger and stressor acts as catalysts for higher levels of functioning Stress & Positive Consequences Little research on how athletes come to view there injuries in a positive manner. One recently study by Udry et al (1997) did involve 21 elite athletes on US Ski Team 95% of the athletes reported more positive consequences from their injuries 80% reported personal growth, psychological skill enhancement,& physical-technical enhancement from being injured Recommendation Recognize that deriving positive consequences takes effort Recognize different problem-solving strategies can be used Injured athletes must not passively assume positive consequence will occur Use reversal strategies Avoid Secondary victimization AT should not trivialize the experiences of the injured athlete Personality Correlates During Injury Rehabilitation Neuroticism Explanatory Style Dispositional optimism Hardiness Neuroticism Abundant evidence that injuries produce generalized negative affect, especially in severe injury. Typical responses in athletes are: Disappointment Frustration Confusion and, Depression There was pain because I had surgery; pain because I knew my career was over. It was probably the moment I suffered the most in my life. It was pain all over.” Maladaptive Behavior & Neuroticism Selective attention to the negative emotions to injury Anger is exhibited (“I was not a nice person when I was injured”) Tendency to rely on inefficient coping strategies Denial, withdrawal, selfblame, emotional venting, disengagement Explanatory Style Pessimistic explanatory style Personality caused:”It my own fault” Stable over time: “I’m never going to play” Global: “the rest of my life” Health effects Immune system function Poorer health Dispositional Optimism Investigations are consistent Cardiovascular and, Immunological function is associated with optimism(Peterson et.al, 1991;Scheiver & Carver, 1987) Optimism mitigates the stress-illness relationship Link between optimism and recovery Hardiness “Constellation of personality characteristics that function as a resistance resource in the encountering of stressful life events”-Kobass, et. al. 1982. P. 169 Components are Commitment-strong beliefs in one own value Challenge-views difficulties to over come Control-sense of personal power Hardiness Link Kobasa (1979) linked hardiness to physical health. Mechanism underlying hardiness seems to be cognitive appraisal and coping processes(Florian et al, 1995; Gentry & Kobasa, 1984) Studies with Athletes Athletes who are high in neuroticism and pessimistic explanatory style display maladaptive behavior which results in longer rehab or incomplete recovery ( Grove, Stewart & Gordon (1990) with athletes with ACL damage Grove & Bahnsen (1997) with 72 injured athletes Formal Assessment Procedures Neuroticism Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQN)-Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975 Explanatory Style Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ)Peterson et al., 1982) Informal Assessment One-to-one visit & pay attention to the athlete comments Fear, sadness, embarrassment, guilt & anger, feelings of being over whelmed by the demands of rehab—signs of neuroticism Ask the “why” statement…. Insight into athlete’s explanatory style Implications “the person that I wanted to talk to the most was the person that was going to help me get better…..We had the best relationship. He/she knew what I was thinking; he/she knew what I was going through. He/she was my athletic trainer.” (Quoted from elite skier, injured athlete) Implication Personality information helps AT to provide a more complete service Highly neurotic athletes are prone to overreact, denial, disengagement, and emotional venting. AT need to: model rational behavior well planned treatments Maintain records of progress Develop psychological skills of cognitive appraisal, coping, and stress management. Implications Injured Pessimistic Athletes feel helplessness and depressed. These athlete fail to follow recommended treatment programs(especially unsupervised aspects). Demonstrate a lack of persistence in the face of poor or slow progress. AT trainer should offer advise in how to cope, prevent athletic isolation, & provide emotional support. Implications Injured athlete low in hardiness worry, experienced depressed moods,& overgeneralize negative aspects of their character. AT need to communicate clearly with the athlete about the severity of injury, get them actively involved in setting rehab goals, use feedback of progress through charts or graphs, and provide self-monitoring strategies such as logs. Psychological Reactions to Injury Stage Model Cognitive Appraisal Model Stage Model Based on death and dying literature Relates to career ending injuries Most important aspects is individuals react differently across the stages. Many AT reject the stage model because each injured athlete act differently. Stage Model & Catastrophic Injury Denial Anger Grief Depression Reintegration Cognitive Appraisal Model Identified 5 components relevant to psychological responses to athletic injury Based on stress and coping process to athletic injury Advantage of this model is it accounts for individual differences in response to athletic injury Personal Factors Self-esteem Neuroticism Pessimism Anxiety Extroversion Injury History Sense of self Sense of Self If someone has only one basis for a sense of self, if that sense of self is threatened (injury), so will the entire person……Erikson, 1968 If the athlete’s sense of self is threatened the athlete will view the injury as severe loss which results in anxiety, depression, or hopelessness (Brewer, 1993). Overestimators Athletes in general perceive injury as more serious than it really is when compared to the AT perception (Crossman & Jamieson, 1985) A group of athletes are overestimators experience greater pain, more anger, withdrawal, and show slow recover. Situational Factors Post injury emotional adjustment is positively related to situational variables and social support. AT needs to manipulate the situational factors and enhance social support. Manipulating the Situational Factors Flexibility in rehab scheduling Communicate with the athlete about the seriousness of the injury Provide a rehab center so it accessible, safe, and friendly Explain the purpose of each protocol and goals of each rehab session Response to Injury The athlete cognitive appraisal of the injury interacts with the personality of athlete and the situational factors surrounding the injury. Perceived severity History of Injury Ability to Cope Emotional Response After cognitive appraisal by athlete about their injury, an emotional response will follow Perceived as threat the athlete will emotional vent, become anger,experience high anxiety, denial, disengagement, and depression If pessimistic engage in negative self-talk, and self-blame. If neurotic engage in loss of self, withdraw, and display changes in their personality. If overestimator become irrational about the severity of injury. Behavioral Consequences After the emotional response the athlete will engage in positive or negative coping responses. Adopt healthy coping responses physically, emotionally or psychologically. Learn new psychological skills and physiological exercise…use injury as personal growth Adopt maladaptive coping responses Career over, learned helplessness, blame others, use other as the excuses, non compliance of rehab Recovery or Delay in Recovery Length and degree of complete recovery in reentry into the sport is dependent upon: Severity and type of injury Athlete’s cognitive appraisal and emotional response to the injury Athlete’s coping resources Interventions both psychologically and physiological Types of Injuries Macrotrauma (acute trauma) Microtrauma (breakdown over time) Different psychological reaction to the type of injury Macrotrauma Rehab proceeds immediately Usually results in clean progression of healing AT and PT have clear cut rehab protocol Athlete most certainly knows the injury could not be prevented and it was caused by a situation usually out of their control. Athlete will bring closure to cognitive appraisal and assume rehab as their rectifying the situation. Micotrauma Usually results from biomechanical overloading Recovery may be much longer with relapses more frequent Athlete experiences a great deal of distress (frustration, anxiety, etc), second guessing, and detachment for the sport is gradual. Athlete will question the AT or PT skills and protocol. Psychological Perspective of Athletic Injuries Summary Stress X Injury relationship needs to assessed. Once athlete are identified with high stress levels there is need for proactive Approach Injuries do have positive consequences if the athlete has experienced a successful rehab. Athlete’s personality is related to length and degree of recovery. Assess the athlete level of neuroticism, explanatory style, optimism, and hardiness Summary (continued) Athlete’s response to career ending injuries reflect the stage model Cognitive appraisal model provide AT why some athlete behave differently when injured. AT should assess the athlete cognitive appraisal of injury through formal or informal means. Athlete’s respond differently when they have macro versus microtrauma injuries. PART II: Patient-Practitioner Interaction of Injury Rehabilitation Patient Practitioner Communication Patient-Practitioner Perceptions Adherence to Rehab Referral Process Ethics & Legality Patient Practitioner Communication Received little AT empirical attention. Studied extensively in medical literature Results have indicated: Poor patient-practitioners communication discourages future use of medical services (Taylor, 1995) Poor patient-practitioners communication hampers adherence to rehab (Meichenbaum & Turk, 1987) Poor Communication Patient Anxiety Inexperience with the medical disorder Lack of intelligence Practitioner Not listening Using jargon Technical language Displaying worry Depersonalize the patient Patient –Practitioner Perceptions Rehabilitation Regimen Athlete and AT have significant disagreement about rehab program (Kahanov & Fairchild, 1994). Patients to expect to complete their rehab on an average 42% quicker then AT estimates. 77% of sport injury patients who were prescribed home rehab exercises misunderstood the rehab program(Webborn, et al, 1997) Patient-Practitioner Perceptions Recovery Progress Perception of poor rehab is linked to negative emotional responses in athletes (McDonad & Hardy, 1990). AT trainers and athlete’s rating of injury disruptiveness is similar but athletes tend to overestimate the severity (Crossman & Jamieson, 1985). Athletes consistently perceive recovery as complete well before AT perception. Coaches do not see “eye to eye” with AT perceptions the athletes return to competition Attribution for Recovery Instilling a sense of self reponsibility for rehab by the athlete (Gordon et al, 1991) Depends on the rate of recovery Slow recovery are less likely to accept responsibility Faster recovery more likely they will engage in their own self-recovery Psychological Distress Emotional distress is inversely related to rehab adherence and outcome. Distress Need to assess distress Adherence & Outcome Adherence to Rehab Adherence rates range from 4091%(Brewer, 2002) Positive determinates of patient adherence: Self-motivation Pain tolerance Being involved and choices Hardiness((Wittig & Schurr, 1994) Negative determinates Ego involvement & Trait anxiety Adherence to Rehab Environmental Factors Positive determinates Self-efficacy of the treatments(Duda, et al,1989) Comfort of rehab setting (Brewer, et al, 1994) Convenience of rehab scheduling(Fields, et al, 1995) Perceived exertion during rehab (Brewer, et al, 1988) AT trainer expectancy of patient adherence. Adherence-Enhancing Strategies Based on previously injured athletes and AT (Fisher, at al, 1993). AT who are caring, honest, & encouraging At who educate the client At who use goal setting and monitor the clients progress AT who do not use threats or scare tactics in gaining adherence Five Practical Suggestions for Enhancing a Working Alliance 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Check preparations Get specifics Listen before you fix Listen for the “but” Value Patient Input Referral Process 5-13% of injured athletes experience clincially meaningful levels of psychological issues Before referring, consult with mental health professionals about the athlete There is no perfect time refer Need to explain to athlete why you are referring them and to whom. Always follow up about the athlete after referral Using the Referral Process Effectively Recognize there are certain conditions which require referral Eating disorders Depression Establish a team of sport-medicine professionals. Team of Sport Medicine Professionals Primary Care Level Secondary Care Level Tertiary Care Level Strategies in Referral Reactive referral Injured athlete shows signs of depression, eating disorders, or anxiety. Unfortunately, the majority of AT (76%) never refer the athlete (Larson, et al., 1996) Proactive referral Preventive approach Provide tracking athlete nutritional requirements for the sport Provide psychological skills training related to management of stress Athlete Perception of Referral In reactive referral, athlete usually is in denial Being referred to psychologist is perceived as weakness Goes against the norm of team and being an athlete In proactive referral, The sport-medicine team is part of the sport Team is made up of specialist the athlete can go to when having difficulty Reducing Problems in being Referred Introduce the sport-medicine team at the beginning of the season Discuss the roles of each member of the team Emphasize that specialists is important in achieving a complete recovery Once referred, keep a complete history including both psychological and medical information Eliminate the feelings of abandonment after being referred Ethical Issues Athletes using steroids Athlete using nutritional supplements Coaches who expect the injured athlete to play in pain Coaches who insists anti-inflamatory drugs and cortizone are part of the training regimen Athlete needs to “make weight” to participate. Ethical Status My belief is that if I had to take an estimate, about 65% of the top five, let’s say top ten in the world in every event, are doing something illegal. That is the growth hormones in the ballistic events and blood doping for distance events. (quote from athlete, Ungerleider & Golding, 1992) Ethics Dr. Park Jong Sei, director of Olympic drug testing in Seoul stated that “as many 20 athletes at the games turned up positive but were not disqualified.” Some coaches have been know to refuse to train athletes who are clean (Voy, 1991) Legal Issues AT will regularly be confronted with evidence of illegal and unethical practices to enhance performance. AMA now recognizes AT as allied health provider. With increase professional status increases vulnerability to lawsuits With open-free standing clinics, AT are now are expected to know more Certification of AT was to protect the public from incompetent and unethical sports professionals. Moral Decisions Need to have a solid personal value system Ask your self these questions: Is may decision compatible with my values? Does it feel right? What is usually done in past when making a similar decision? By doing this, what am I saying about myself? (Simon, Howe, & Kirschenbaum, 1974) These question will help you to establish consistency and clarity!! NATA Ethical Standards 5. Prevention Recognition and Evaluation Management/Treatment Rehabilitation Organization & Administration 6. Education & Counseling 1. 2. 3. 4. TASK 3: NATA Education Domain Directs the athlete to professionals in order to receive consultation for social/ and or personal problems by establishing a referral procedures. knowledge of situations requiring consultation Knowledge of available professionals Knowledge of referral procedures NATA Code AT who engage in counseling athletes with social and/or personal problems would be considered incompetent by the NATA AT are expected to have knowledge in the area of phychological readiness for the return to activity skill in evaluating the athlete’s psychological status, And implication of unhealthy situations (e.g. substance abuse, eating disorders, victim of assault, abuse, etc.) Penalty Violate the clients right of confidentiality is extreme. Monetary damage Loss of job Loss of certification Loss of Lesser ethical breaches Loss of certification Censure to expulsion from AT organization Physical Activity and Eating Disorders Individuals often have unrealistic expectations related to weight management and PA. Images of the ideal body thin and fit for women fit and muscular for men Dieting is often used to attempt to model these ideals. Davis (2000) noted 80% of female with eating disorders exercised excessively Anorexia Nervosa 1. Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height 2. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though under weight 3. Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, unduly influence of body weight Bulimia Nervosa 1. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. a) a discrete period=more food than most people b) a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode 2. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior in order to prevent weight gain 3. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least twice a week for three months Comparison of Athletes to Nonathletes Athletes as a population might be at-risk 1) Societal norms --favor a lean physically fit physique -- these societal norms are salient for athletes 2) Psychological characteristics consistent with high-level athletic achievement (perfectionism, motivation), are also evident in individuals with eating disorders Athletes experience more eating disorder symptoms than do nonathletes. Comparison of Athletes to Nonathletes Hausenblas and Carron (1999) metaanalysis Female athletes self-reported more bulimic (ES = .16) and anorexic (ES = .12) symptoms compared to females from the general population Male athletes self-reported more bulimic (ES = .30) and anorexic (ES = .35) symptoms compared to males from the general population. Comparison of Athletes to Nonathletes Hausenblas and Carron (1999) metaanalysis Male athletes in aesthetic and weightdependent sports self-reported more bulimic and drive for thinness symptomatology versus male comparison groups. Females in aesthetic sports self-reported more of the tendencies to report anorexic symptoms (ES = .38) Steroid Abuse and Physical Activity Steroids-- man-made versions of the primary male sex hormone, testosterone Athletes are not the only population using steroids. Fireman Policemen Military personnel Personal trainers Regular exercisers Steroid Abuse and Physical Activity How prevalent is steroid use? The first nationwide survey of steroid use among teenage boys 1988 About 7% of high school seniors had used steroids. Prevalent in wrestling and football 35% of steroid users did not participate in any sport Steroid Abuse and Physical Activity Reasons for use Improve athletic performance (47%) Improve physical appearance (27%) Prevent or treat injury (11%) Fit in (7%) The results of the Buckely et al. (1988) study subsequently have been confirmed by more than 40 national, regional, and local studies Steroid Abuse and Physical Activity Pope & Katz (1994) examined the psychological effects of steroid use Urine samples were obtained to assess actual steroid use. 23% reported experiencing major mood disturbances (i.e., mania, anxiety, depression, or major depression). Muscle Dsymorphia A large variety of terms have been used to describe a form of body image distortion in which the individual perceives him/herself as unacceptably small. (a) pathologically preoccupied with the appearance of the whole body (b) concerned that they are not sufficiently large or muscular (c) are consumed by weightlifting, dieting, and steroid abuse. Summary Part II Poor communication between athlete and AT & PT relates to: Athlete’s compliance of Rehab Most athlete’s will have heightened levels of anxiety Depersonalizing the athlete, using technical jargon, and not listening to the athlete are poor communication strategies. Summary II (Continued) Perception of poor rehab (time) is linked to allot of negative responses Most athletes overestimate,and disagree with the AT or PT on when they can return to play. Most coaches disagree with AT or PT when the athlete should return to play. Summary II (continued) The athlete who is self-motivated, optimistic, high self-efficacy, high pain tolerance, hardiness, and provided choices rehab successfully. Ego involved athletes highly neurotic, pessimistic, lowly motivated, low pain tolerance, and low self-efficacy rehab will be longer and unsuccessful. Summary II (continued) AT must refer athletes if they experience signs of depression, high anxiety, abuse, assault, and eating disorders. AT is required to develop and know their referral procedures, the sport-medical team, and knowledge in signs and assessment of psychological disorders. Part III: Specialized psychological interventions Social Support Interventions Healing Imagery Goal Setting Positive self-talk Stress-Management Strategies Social Support Interventions Supported athletes are generally more mentally and physically healthy due to health sustaining and stress reducing functions of social support (Shumaker & Brownell, 1984) Coach Parents Teammate AT & PT Social Support Interventions Social support is critical in the rehab of the injured athlete (Rotella & Heyman, 1986) Social support is an effective psychological technique that motivates the athlete during rehab (Hardy & Crace, 1990) Social Support Emotional support Informational support Behaviors that comfort and indicate that they are your side. Listening Behaviors that acknowledge your efforts, helps confirm your perceptions Tangible support Financial assistance, and rehab knowledge Providing Emotional Support Listen carefully Keep in contact with coaches, teammates, AT, PT, and parents. Create an open environment Providing Informational Support AT should develop a context expertise in as many injuries as possible. Deliver effective feedback Use of technical modalities Create sharing opportunities between injured athletes Have successfully rehab athletes with similar injuries openly discuss the issues Tangible Support NATA trainer needs to know rules and regulations of the sport about the type of support from booster, alumni, coach, etc. Let the athlete know exactly what you can and will do as well as what you cannot and will not do! Best tangible support is services received at the time it is requested. Refrain from putting the athlete in a state of indebtedness……give it freely. Healing Imagery Healing imagery in which athletes tried to see and feel the body parts healing Imagery during physiotherapy when they imagined the treatment promoting recovery Total recovery imagery in when they imagined being totally recovered Basic Components of Healing Imagery Relax mentally and physically Mentally connect with the injured body part and imagining healing taking place using all the senses See and feel how the body exactly as one would like it to be. Imagine the body fully functioning and performing well in the sport or situation. Healing Imagery Arnheim (1985) had the athletes imagine scar tissue being gobbled up by “Pac Men” Searingen (1984) had athlete draw pictures depicting the healing process around the factured site of the bone. Healing Imagery Create a series of imagines that are progressional of one’s self from a injured state to full recovery. Process-oriented selves Example of Process-Oriented Selves (Markus & Ruvolo, 1989) Self Self Self Self Self Self Self #1: #2: #3: #4: #5: #6: #7: Knee at 90 degrees Strut your stuff Hurt to get better! Spring Forward Let’s Play Dribble, Drive, and Dive No brace Is Goal Setting Effective? Research has shown that goal setting is an extremely powerful technique for promoting rehab, but it must be correctly implemented. Why Goal Setting Works Key: Athletes who set performance (rather than outcome) goals experience less anxiety and more confidence and satisfaction during rehab Principles of Goal Setting 1. Set specific goals. Specific goals, as compared with general “do your best” goals, are most effective for producing behavioral change. - I am going to my best in completing all my exercisers. -I am going to put forth 100% each rehab session. 2. Set difficult but realistic goals. Goals should be “moderately” difficult. Principles of Goal Setting 3. Set long- and short-term goals. Link long- and short-term goals to the outcome which is full recover and return to the sport. 4. Set performance and process goals, as well as outcome goals. For every outcome goal, set several performance and process goals that will lead to the desired outcome. Principles of Goal Setting 5. Set daily rehab session goals 6. Record goals. “Ink it, don’t think it.” 7. Develop goal-achievement strategies. Develop specific goal-achievement strategies that include how much and how often things will be done in an effort to achieve full recovery. Be flexible, however. Principles of Goal Setting 8. Consider participants’ personalities and motivations. Consider factors such as self-motivation, optimism, hardiness, anxiety, ego involvement. 9. Foster an individual’s goal commitment. Promote goal commitment by social support, frequent feedback, and reassessment. Ways that help athletes commit to rehab goals Write them down State them to others Keep a log Provide the athlete constant feedback about their rehab Incorporate them into rehab session Goal Setting System Developed by Dr. Millslagle Based on wheel of awareness model used in athletic performance Self-Talk Key to cognitive control How does positive self-talk help? It helps the injured athlete to: Stay appropriately focused on the present Foster positive expectations Common Uses of Self-Talk Skill acquisition Changing bad habits Attention control (being in present) Creating mood Controlling one’s effort Building self-confidence Injury rehabilitation Exercise Adherence What type of self-talk do you use? Positive or Negative? What do you say to yourself after the injury? What thoughts appear during rehab? When do you use self-talk? Common themes that appear across the rehab? What cue words do you use in self-talk? Cognitive Techniques to Control the Mind Thought stoppage Changing negative thought to positive thought! Reframing Rational thought Designing coping and mastery self-talk tapes Measuring Anxiety Physiological signs (heart rate, respiration, skin conductance, biochemistry) Global and multidimensional self-report scales Trait and State Anxiety Relationship State anxiety: “Right now” feelings that change from moment to moment. Trait anxiety: A personality disposition that is stable over time. High versus low trait anxious people usually have more state anxiety in highly evaluative situations. Recognize Symptoms of Arousal and State Anxiety Cold, clammy hands Constant need to urinate Profuse sweating Negative self-talk Dazed look in eyes (continued) Recognize Symptoms of Arousal and State Anxiety Feel ill Headache Cotton (dry) mouth Constantly sick Difficulties sleeping (continued) Recognize Symptoms of Arousal and State Anxiety Increased muscle tension Inability to concentrate What can the AT or PT do? Change the athlete perception of severity and importance of the injury Reduce uncertainity about the injury Anxiety and Rehab How anxiety affects rehab depends on an individual’s interpretation. Anxiety can be interpreted as pleasant/excitement or as unpleasant/anxiety. Anxiety interpreted as pleasant facilitates performance. (continued) Anxiety and Rehab Anxiety interpreted as unpleasant inhibits rehab. Bottom line: Athlete’s interpretation of anxiety determines it’s affect on rehab. How the athlete should view anxiety An athlete’s interpretation of anxiety symptoms is important for understanding the anxiety-performance relationship. Viewing anxiety as a facilitator can promote performance. Significance of All these Anxiety–Performance Views Anxiety is multifaceted. Anxiety Physical activation Interpretation of anxiety Significance of All the Anxiety–Rehab Views When anxiety is to high, athletes time and extent of recovery is hindered. • Lowly skilled, young athletes or first time injured athletes are less able to control their anxiety and more apt to be overly aroused. Anxiety Reduction Interventions Matching Hypothesis Somatic anxiety Cognitive anxiety Anxiety–Reduction Techniques Somatic Anxiety Reduction Breath control Learn to control your breathing in stressful situations. When calm, confident, and in control your breathing is smooth, deep, and rhythmic. When under pressure and tense your breathing is short, shallow, and irregular. Center Breathing Session Anxiety–Reduction Techniques Somatic Anxiety Reduction Progressive relaxation Learn to feel the tension in your muscles and then to let go of this tension. Progressive Relaxation Session Anxiety–Reduction Techniques Somatic Anxiety Reduction Biofeedback Become more aware of your autonomic nervous system and learn to control your physiological and autonomic responses by receiving physiological feedback not normally available. Anxiety–Reduction Techniques Cognitive Anxiety Reduction Relaxation response Teaches individuals to quiet the mind, concentrate, and reduce muscle tension by applying the basic elements of meditation. Anxiety–Reduction Techniques Cognitive Anxiety Reduction Autogenic training A series of exercises designed to produce two physical sensations—warmth and heaviness—and, in turn, produce a relaxed state. Autogenic Relaxation Session Anxiety–Reduction Techniques Multimodal Anxiety Reduction Stress– An individual is exposed to inoculation training (SIT) and learns to cope with stress (via productive thoughts, mental images, and selfstatements) in increasing amounts, thereby enhancing his or her immunity to stress. Psychological Interventions for AT Summary Provide social support “Time out” provides opportunities Involve successfully rehab athletes Set Rehab Goals Mention to the athlete that imagery promotes healing Listen closely to the athlete’s needs Psychological Intervention for AT Summary Be flexible in your attitude and approach about the athlete path to recovery Mention that stress management techniques help. Mention self-talk promotes the time of rehab Psychological Interventions for Athletes (Summary) Stay involved in the sport Set daily goals Develop a physiotherapy plan Do mental imagery Use positive self-talk Emphasize positive aspects of the recovery Take advantage of the “time out” Practice relaxation techniques Part IV: Bio-Psychological Aspects of Pain Dr. Duane Millslagle Associate Professor University of Minnesota Duluth Outline Biological Factors Psychological Factors Pain Assessment Pain Management Biology of Pain Pain is a “sensory and emotional” experience (p.226; Merskey, 1986) Medical community attempts to explain as either mental or physical Medical community view misleads the athlete One’s perception of their pain results in many cognitive-emotional experiences Pain Experience Multistage process built on a complex anatomic network and chemical mediators that produce pain This multistage process of the nervous system is called Nociception. Nociception TRANSDUCTION TRANSMISSION MODULATION PERCEPTION TRANSDUCTION COMPONENT Noxious stimuli (injury) are translated into electrical activity at the sensory endings of the nerves (site of injury) Pain triggers two sets of receptors: High threshold mechanoreceptor Polymodal receptors Transmission Component The electrical activity (impulses) are propagated (sent) through out the sensory nervous system Modulation Component Sensory impulses are modified (received, registered, and evaluated on severity and site) neurally involving the central cortical track and peripherial sensory inputs. Perception Component Transmission, transduction, and modulation culminates in a cognitiveemotional (perceptual) experience of pain. The Transduction Component How pain is triggered? Sensitization of Pain Persistent Pain Syndromes How is pain triggered? Two sets of receptors are activated due to a injury Mechanorecptors High threshold receptors (activated when high noxious signal) which sends signals with relative speed Polymodal receptors Respond to thermal, chemical and mechanical stimuli and are relatively slow in transmission Continue to fire after cessation of painful stimuli Sensitivity to Pain Unfortunately these receptors have a lower threshold of response with repeated exposed similar stimuli. Higher sensitivity to pain-producing stimuli Pain occurs in ordinarily nonpainful stimuli “This process is called Sensitization Types of Sensitization Occurs when there is repeated exposure to severe pain over days and weeks. Persistent pain syndomes Myofascial and Sympathetical Persistent Pain Syndromes Myofascial pain syndrome Musculosketal dysfunction Indicated by points of tenderness when activated triggers pain (Fine & Petty, 1986) Sympathetical pain syndrome Pain that occurs in the arms and legs Characterized by hypersensitivity of the skin and burning pain (Roberts, 1986) Transmission Component Pain is transmitted via peripheral nerves to the spinal cord Spinal cord acts as neurosensory switching station Information from periphery is received centrally (spinal cord) and from the brain via the descending track All this information converges using similar and common neurosensory pathways. Gate Control Theory of Pain (Melzack and Wall, 1965) The processing center in the spinal cord may either decrease or increase the intensity of pain as a neuroelectrical phenomenon and so result in the perception of relatively lesser or greater pain than initially signed. Importance of Gate Theory Explains why various therapeutic modalities ranging from cryotherapy to ultrasound to acupuncture to massage control the efficacy of pain. Modulation The pain signal in spinal cord ascends to the higher cortical centers of brain which evoke a emotional-reaction. One’s Perception of Pain Perception of Pain Based upon summation of inputs Awareness of seriousness of injury Meaning of the injury Present state of mind Once registered as perception, pain sets off a cascade of electromechanical events via feedback loop within the nociceptive system that influences pain transmission and psychological status. Reaction to Pain is Mystery? One reaction to pain can produce a wide ranging of psychological moods. Sock………………..Enhanced Mood May be due to the role of: endorphins (pain inhibitor), serotonin (pain intermediary), sensitization and, pathways that transmit pain & mediators Psychological Factors Goal of pain is to give it meaning (perception). Pain is interpreted due to: Prior experience Current context Most Important Element Most important element of meaning is the assumed status of pain as benign, or as a sign of injury. No problem! This a routine pain. Oh no! I’m really hurt! Understanding Pain Understanding if pain as an injury triggers: psychological coping, Awareness of functional limits on athletic ability, Memory of similar painful events, Self-assessment of injury and, Social psychological reaction by teammates, coaches, etc. Pain Assessment More complex and disstressing the injury more comprehensive the approach. Injury may only involve the primary level Injury may involve primary, and secondary levels. Proven Techniques in Assessing Pain 1. 2. 3. 4. Have the athlete rate on a scale 0-10 the intensity of pain. Have the athlete indicate the quality of pain (burning, stabbing, aching, etc) Daily self-report “pain at its worst” and “pain at is least” Indentify specific situations that increase or decrease pain (specific movements or exercises) Pain Management Common pain management treatments are: Ice Untrasound TENs Diathermy Electrical stimulation Acupressure, Massage, and Mobilizing coping resources. Four Pillars of Psychological Rehab 1. 2. 3. 4. Education Goal Setting Social Support Mental Training The first three fall within the AT and PT’s scope AMA responsibility and ability. Primary Responsibility of AT Differentiate between benign pain and pain associated with reinjury and to determine a relatively safe level of physical activity. Create a sense of calm and security in the midst of pain and fear of further injury Once in rehab, education Nature of injury Rehab strategies Identify pain as a routine aspect of rehab Part IV: Integrated Rehabilitation Model:A Team Approach Dr. Duane Millslagle Associate Professor University of Minnesota Duluth Psychological Model of Psychological Response to Athletic Injury and Rehabilitation Model of Postinjury Responses Identifies the sports medicine team members whom injured athletes at different levels of sport participation may interact. Identify the social-psychological impact of athletic injury(Anderson & Williams, 1988) Incorporated the stress model of injury (Wiese & Weiss, 1987) Ultimate Goal of the Model Clinical Model in assessing postinjury cognitive and emotional responses for planning appropriate physiological and psychological interventions. Members of Sports Team by Competitive Level Who should be involved at each level. Athletic Trainers Role Controlled communication is a primary responsibility during initial management of injury (Wiese & Weiss, 1987) Role of first responser What they say How they say it Diagnoses must be avoided Be reassuring, calm, and professional Role of the Athletic Trainer At High School and College level the AT plans, monitor, and evaluates rehab programs this means the AT has constant contact with the athlete. Rehab must be viewed as an educational process Psychosocial role is vital Support, encouragement, and reassurance Positive communication that includes good listening skills Focus is on adherence to rehag through praise, rewards, and corrective feedback. Role of Athletic Trainer Trainers help the athlete set performanced based goals Trainers need to find appropriate motivation strategies Trainers need to provide social support Athlete needs to maintain their social support network (coaches, teammates, etc) Coaches Role Coaches pay little attention to injured athletes The usual causes are the coach knows little about the athlete’s life outside of sport, the rehab required, athletes attempt to return to competition, and stress response of injury on a athlete. Coaches Role They need to care about injured athlete Understand the rehab Keep the injured athlete integrated with the team Attend practice Use them as referee in scrimmage Evaluate others performance Keep score/times/statistics Overall Summary Discussed 5 areas Psychological Perspective of Athletic Injury Patient-Practitioner Interaction in Sport Injury Rehabilitation Specialized psychological interventions in Sport Injury Rehabilitation The Bio-psychological perspective of pain Integrated Rehabilitation Model:A Team Approach Overall Summary Psychological Perspective Life stress X Injury Rate Relationship Proactive Approach Personality Affect on Injury Recovery Stage and Social Appraisal Model Type of Injury: Macro and Micro Overall Summary Patient-Practitioner Interaction Communication Adherence determinates Positive: Self-motivation, pain tolerance, choice, and hardiness Negative: Ego involvement & trait anxiety Referral Process Sports Medicine Team Ethical Issues Overall Summary Specialized Interventions Goal setting Social support Healing imagery Social support Overall Summary Psychology of Pain “Sense and emotional experiences” Nociception Receptors Sensitivity to Pain Gate Control Theory Pain Assessment Pain Management Overall Summary Integrated Rehab Approach Know the roles of each member Preinjury factors Personal history, situational factors, social, and environmental moderators Responses to injury Cognitive, emotional, & behavioral Physical & Psychological Recovery Process The End Areas which you should study about are: Using imagery in rehabilitation Working with athletes with permanent disabilities Role of Sport Psychologist Usually sees the player within a few days of injury First meeting Interview the athlete alone about history and nature of injury Conduct it the ones office Interview format of first meeting Explain the role of sport psychologist Qualification Have the athlete complete the Emotional Response of Athletes to Injury Questionaire (ERAIQ) –Smith, Scott & Wiese, 1990)