Labor in the Gilded Age - Arlington Public Schools

advertisement

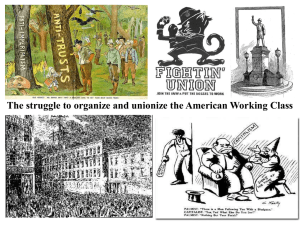

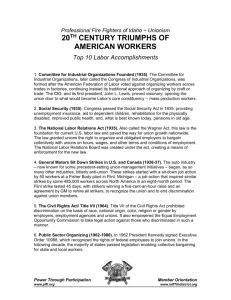

Organized Labor (Unions) Labor laws were passed after the disastrous 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire. 146 people were killed because the company owners had locked doors in an attempt to keep the workers from leaving. In the mid-19th century, the vast majority of American work was still done on the farm. By the turn of the 20th century, the United States economy revolved around the FACTORY. Most Americans living in the Gilded Age knew nothing of the millions of Rockefeller, Carnegie and Morgan. They worked 10 hour shifts, 6 days a week, for wages barely enough to survive. Children as young as eight years old worked hours that kept them out of school. Men and women worked until their bodies could stand no more, only to be released from employment without retirement benefits. Medical coverage did not exist. Women who became pregnant were often fired. Compensation for being hurt while on the job was zero. This 1899 political cartoon, published in The Verdict, represents the growing disparity between the rich and poor classes in America. This disproportion fomented the formation of anti-trust laws in the following decade. Come Together Soon laborers realized that they must unite to demand change. Even though they lacked money, education, or political power, they knew one critical thing. There were simply more workers than there were owners. UNIONS did not emerge overnight. Despite their legal rights to exist, bosses often took extreme measures, including intimidation and violence, to prevent a union from taking hold. Workers, too, often chose the sword when peaceful measures failed. Many Americans believed that a violent revolution would take place in America. How long would so many stand to be poor? Industrial titans including John Rockefeller arranged for mighty castles to be built as fortresses to stand against the upheaval they were sure was coming. Slowly but surely unions did grow. Efforts to form nationwide organizations faced even greater difficulties. Federal troops were sometimes called to block their efforts. Judges almost always ruled in favor of the bosses. Illinois Labor History Society Chicago "Anarchists." In 1886, protesting for an 8-hour work day led to the Haymarket Riot. The workers often could not agree on common goals. Some flirted with extreme ideas like Marxism. Others simply wanted a nickel more per hour. Fights erupted over whether or not to admit women or African Americans. Immigrants were often viewed with hostile eyes. Most did agree on one major issue — the eighthour day. But even that agreement was often not strong enough glue to hold the group together. Organized labor has brought tremendous positive change to working Americans. Today, many workers enjoy higher wages, better hours, and safer working conditions. Employers often pay for medical coverage and several weeks vacation. Jobs and lives were lost in the epic struggle for a fair share. The fight sprouted during the Gilded Age, when labor took its first steps toward unity. It began with the Great Upheaval. Labor vs. Management ILGWU Archives. Kheel Center. Cornell University "Holding the Door Shut," a political cartoon depicting the cruelty of management in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist fire, in New York City. The battle lines were clearly drawn. People were either workers or bosses, and with that strong identity often came an equally strong dislike for those who were on the other side. As the number of self-employed Americans dwindled in the Gilded Age, workers began to feel strength in their numbers and ask greater and greater demands of their bosses. When those demands were rejected, they plotted schemes to win their cases. Those who managed factories developed strategies to counteract those of labor. At times the relationship between the camps was as intellectual and tense as a tough chess match. Other times it was as ugly as a schoolyard fight. Strikes, Boycotts, and Sabotage The most frequently employed technique of workers was the STRIKE. Withholding labor from management would, in theory, force the company to suffer great enough financial losses that they would agree to worker terms. Strikes have been known in America since the colonial age, but their numbers grew larger in the Gilded Age. Most 19th century strikes were not successful, so unions thought of other means. If the workers at a shoe factory could garner enough sympathy from the local townspeople, a BOYCOTT could achieve desirable results. The union would make its case to the town in the hope that no one would buy any shoes from the factory until the owners agreed to a pay raise. Boycotts could be successful in a small community where the factory was dependent upon the business of a group of people in close proximity In desperate times, workers would also resort to illegal means if necessary. For example, SABOTAGE of factory equipment was not unknown. Occasionally, the foreman or the owner might even be the victims of worker-sponsored violence. "Strike, Don't Scab" Poster Management Strikes Back Owners had strategies of their own. If a company found itself with a high inventory, the boss might afford to enact a LOCKOUT, which is a reverse strike. In this case, the owner tells the employees not to bother showing up until they agree to a pay cut. Sometimes when a new worker was hired the employee was forced to sign a YELLOW-DOG CONTRACT, or an ironclad oath swearing that the employee would never join a union. Strikes could be countered in a variety of ways. The first measure was usually to hire strikebreakers, or SCABS, to take the place of the regular labor force. Here things often turned violent. The crowded cities always seemed to have someone hopeless enough to "CROSS THE PICKET LINE" during a strike. The striking workers often responded with fists, occasionally even leading to death. Prior to the 20th century the government never sided with the union in a labor dispute. Bosses persuaded the courts to issue injunctions to declare a strike illegal. If the strike continued, the participants would be thrown into prison. When all these efforts failed to break a strike, the government at all levels would be willing to send a militia to regulate as in the case of the Great Upheaval. What was at stake? Each side felt they were fighting literally for survival. The owners felt if they could not keep costs down to beat the competition, they would be forced to close the factory altogether. They said they could not meet the workers' unreasonable demands. What were the employees demanding? In the entire history of labor strife, most goals of labor can be reduced to two overarching issues: higher wages and better working conditions. In the beginning, management would have the upper hand. But the sheer numbers of the American workforce was gaining momentum as the century neared its conclusion. Notable Labor Strikes of the Gilded Age Strikes have played a significant role in the economic, political, and social life of the United States throughout its history. From strikes by shoemakers, printers, bakers, and other artisans in the era of the Revolution through the bitter airline strikes two centuries later, workers repeatedly tried to defend or improve their living and working conditions by collectively refusing to work until specific demands were met. Since the early 1880s, when reliable statistics were first compiled, American workers have struck with a frequency roughly equal to that of their peers in Europe. Strikes in the United States, however, have tended to last longer than elsewhere, with a mean duration between 1881 and 1974 of twenty days. Accordingly, the total number of workdays lost in strikes proportionate to the size of the work force has been higher in the United States than almost anywhere else in the world. The United States also has had the bloodiest labor history of any industrial nation. The first strike fatalities were two New York tailors, killed in 1850 by police dispersing a crowd of strikers. Since then, according to one estimate, well over seven hundred people - mostly strikers - have died in strike-related violence, and the total may be much higher. Some died in famous incidents, such as the 1913 Ludlow Massacre, when National Guardsmen attacked a tent colony of striking Colorado miners, or the 1937 Memorial Day Massacre, when ten supporters of a steel strike were killed by Chicago police. Most, however, died in little-noted confrontations with company guards, private detectives, scabs, or police. Although wage disputes have been the single most common cause of strikes, workers have walked off their jobs for many reasons, including efforts to win union recognition, shorten the workday, gain or defend control over the work process, improve working conditions, and protest the disciplining of unionists. Strikes have been called to exclude nonwhites or women from jobs and, more rarely, to protest racial discrimination. Unlike elsewhere, political strikes over non-work-related issues have been uncommon. Strikes have played a major role in both the rise and fall of unions (though many have occurred without union involvement). Often strikes have stimulated the formation of new unions or union federations. The first citywide labor federations, formed in the 1820s and 1830s, grew out of strikes by artisans seeking to shorten their workday. Over a century later, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was indirectly an outgrowth of a wave of strikes by industrial workers. Conversely, failed strikes have destroyed many unions. The American Railway Union, for example, was unable to survive the defeat of its 1894 strike against the Pullman Car Company. More recently, the mass firing of striking air traffic controllers by the Reagan administration led to the demise of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization. IMMIGRATION FROM 1870 TO 1920: ---About 24 million immigrants. 60% from Southern and Eastern Europe, about 25% Northern Europe (Germany, Ireland, Scandinavia), 15% other (Asian Mexican, etc). Approximately 35,000 workers a year were killed annually in work-related accidents from 1880 to 1900. Injured workers totaled another 536,000. Between 1905 and 1920, there were an average of 2000 fatal accidents in the coal mining industry every year. The unemployment rate before World War I rarely fell below 8% for full-time jobs. Underemployed workers probably counted for about 25% of the work force. A minority of urban workers had full-time year-round work. Before 1920 about one in every four non-farm children under fourteen worked full-time. Before the 1930s less than half of Americans received more than a grade school education. The Great Strike, 1877 In the era of dramatic industrialization following the Civil War, the most powerful of the big business corporations were the railroad companies. In order to protect their profits during the economic depression that had begun in 1873, they companies had reduced the pay of railroad workers by ten percent. In 1877 they announced another ten percent reduction in the workers' pay, and also that railroad employees would be required to use company hotels when away from home, which meant a further reduction in real wages. On top of this, they decided to reduce the work-force - which meant unemployment for some and intensified labor for those remaining. On July 16, a spontaneous strike erupted in Martinsburg, West Virginia and quickly spread to cities from St. Louis and Chicago to New York and Baltimore - hitting Pittsburgh on July 19. To "keep the peace" and break the strike, state militia units from Philadelphia were ordered to Pittsburgh. (Militia units from Pittsburgh were deemed unreliable because they sympathized with the strikers.) On July 21, six hundred troops arrived from Philadelphia. Led by Superintendent Robert Pitcairn of the Pennsylvania Railroad and a posse of constables with arrest warrants for the strike leaders, they found themselves confronted by crowds of men, women and children. The crowds, loudly protesting the troops' presence and expressing support for the strikers, sought to prevent military action. The militiamen responded with a bayonet charge that resulted in injuries and provoked a hail of rocks from some sections of those assembled. The troops then opened fire on the unarmed men, women, and children, scattering them - and leaving at least twenty dead (including one woman and three small children) and twenty-nine wounded. Workers from other cities and towns in Pennsylvania joined in the strikes or in rallies and meetings supporting the strike. General strikes, mass demonstrations, and sometimes violent confrontations rocked cities in many other states as well, though none exceeded the violence of the Pittsburgh battles. On July 26, however, regular troops of the U.S. Army joined with state militia units to take control of the city and reopen all railroad operations in Pittsburgh and Allegheny City. The strike was systematically broken throughout the country by similar means by the end of July. This was the first time in U.S. history that federal troops were utilized against strikers and labor protests Haymarket Riot, 1886 Terrence Powderly called for the Knights of Labor to participate in a planned one-day strike on 1 May in support of the eight-hour day. (40,000 to 60,000 participated). 3 May -- six strikers were killed at the McCormick Reaper Manufacturing Company, after police fired into the crowd who had attacked strikebreakers 4 May -- 13 - 1400 participated in a meeting at Haymarket Square, called by anarchist August Spies, Knights of Labor, and many socialists unions and international anarchists, protesting the use of police force to disperse strikers. At 10 P.M. when 180 police arrived to order the crowd out, a bomb thrown into their midst killed 7, and wounded at least 60. It was assumed that an anarchist threw the bomb and raids were conducted on all known radical groups, including trade union leaders. Judge Joseph E. Gary presided over the trial of Samuel Fielden, speaking when the bomb was thrown, August Spies, Albert Parsons, Michael Schwab, Adoph fisher, George Engel, and Oscar Neebe, who were charged with conspiring to kill. Although no evidence linked specific persons to the incident, the prosecution focused on their radical beliefs and advocacy of violence to achieve goals. This political trial resulted in 7 convictions (the 8th defendant hung himself). Four were sentenced to death (Spies, Parsons, Fisher, Engel), two to life in prison (Fielden, Schwab), one to 15 years (Neebe). They are found guilty on the grounds that it is not necessary to plan a murder for members of a conspiracy to be murderers or accessories before the fact As a result, an anti-radical and anti-union feeling swept the American public mind. Homestead Strike - July 1892 5,000 steelworkers struck Andrew Carnegie's steel plant near Pittsburgh PA. A pitched battle erupted between the strikers and 300 Pinkertons hired by plant manager Henry Clay Frick who had been hired to protect the strikebreakers. Seven guards were killed. 9 July - 7,000 state troopers were sent in by Governor Pattison. 15 July - the steel mill was reopened by strikebreakers. By Nov 14, Frick had broken the 24,000-member Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers and the strike ended. Pullman Strike - 1894 George Pullman , Pullman Palace Car Co., had established a model town for his workers near Chicago which promoted a clean healthy atmosphere, giving Pullman a public image as a benevolent, paternalistic industrial captain. The panic of 1893, worse in US history at that time, caused a wage cut by 1/3, but no lower rent on company housing nor price reduction at company stores. When Pullman fired a suspected union organizer, a strike grew ugly by 1894. Eugene Debs , leader of the American Railway Union , aided strikers by refusing to handle railroads using Pullman cars, encouraging other unions to join. The strike was ended by a court injunction, based on the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, after which President Cleveland sent in 10,000 federal troops (because of "interference" with the US mail), who along with 2,000 state troops smashed the ARU. Pullman workers exit the factory gates after a day's work. Most employees walked the short distance to their nearby Pullman-owned homes and apartments.