Using Mixed Methods to Measure and Monitor Empowerment

advertisement

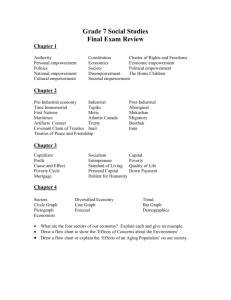

Using Mixed Methods to Measure and Monitor Empowerment in Projects and Programs: Bangladesh, Ghana and Jamaica Nora Dudwick (PRMPR) Jeremy Holland (OPM) Gil Yaron (GYA) PRMPR June 23, 2008 Outline of presentation • Empowerment: what is it and why measure and monitor it? • Bangladesh: Measuring empowerment impacts of social safety net programs on women • Ghana: Measuring empowerment outcomes on water, education and infrastructure beneficiaries of a rural CDD project • Jamaica: Community-based monitoring of social policy outcomes, with a focus on youth-police relations • Conclusions: Lessons learned and implications 2 for monitoring empowerment Why measure empowerment? • The WDR 2000/1 identified “empowerment” as an important development objective • “Empowerment” is closely linked to other corporate agendas of “social accountability,” and the “demand for good governance” • Empowerment enhances people’s choices and opportunities • While a legitimate goal in and of itself, evidence suggests that empowerment improves poverty reduction outcomes 3 Operationalizing empowerment • Empowerment: the interaction of agency and opportunity structure • Agency can be measured through proxies -- the material, financial, social, human, informational, psychological and other assets that people deploy to achieve their goals • Opportunity structure: the formal and informal institutions (“rules of the game”) that constrain or facilitate people’s ability to exercise agency 4 Why use mixed methods? • Access to most assets can be measured by indicators (but qualitative methods better at evaluating psychological, social assets) • Institutional context can be only partially measured by indicators, and calls for qualitative methods • Empowerment (as transformative choice) is difficult to measure quantitatively and benefits from a mixed method approach • ME pilots combined questionnaires, focus groups, Community Score Cards, individual interviews, and rapid ethnography 5 Aim of Measuring Empowerment project • Operationalize empowerment and identify indicators for specific project, program and policy contexts • Go beyond looking at access and satisfaction (beneficiary model) to look at people’s ability to make choices and demand better services • Pilot a cost-effective tool for producing timely feedback to projects, programs & policies and increasing the evidence base for policy makers • Each pilot was undertaken in conjunction with ongoing in-country monitoring of specific project, program, or policy outcomes • TFESSD activity, supported by Country Team and Government expertise in each country 6 Measuring empowerment: The challenge • Meaning: Can we capture the essence of empowerment? Can we observe changes that are meaningful in both direction and magnitude (i.e. identifying whether a person or group is “more empowered” and “how much more empowered”)? • Causality: Can we attribute cause and effect to a dynamic, relational and cross-sectoral phenomenon? How can we measure implicit choice which may not be observable (i.e. people may choose not to choose)? • Comparability: Can we aggregate data so that conclusions about empowerment impacts and changes can be inferred for larger population groups? 7 BANGLADESH: Empowerment impacts of Social Safety Net Programs on women 8 Bangladesh - motivation The Bangladesh PRSP emphasises the: – Role of Social Safety Net Programs (SSNP) in reducing poverty – Need to focus on the empowerment of women The substantial literature on women’s empowerment in Bangladesh does not treat SSNP in detail It was possible to explore this issue by adding TFESSD funds to an existing JSDF-funded survey of SSNP being implemented by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 9 Bangladesh - context The aim of the survey was to measure the empowerment impacts on women of the following SSNP: 1. Food-for-work (FFW) 2. Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) 3. Primary Education Stipend program (PESP) 4. Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) 5. Old Age Allowance Scheme 6. Allowance for Widowed, Deserted, and Destitute Women 7. Allowance for Distressed Disabled Persons 10 Bangladesh – methodology overview FGD (72) SSI analysis Household Survey (2741) Beneficiaries: ordered logit Community Survey (69) All: Propensity score matching Women’s Survey (2741) 11 Bangladesh – Empowerment indicators 1 Women’s questionnaire: • Control over assets (husband, self, joint, others) • Participation in village meetings and elections (& if not, why not) • Participation in household decision making (h, s, j, o) including joining organisations, economics & child related • Autonomy (visiting & purchases) & domestic violence 12 Bangladesh – Empowerment indicators 2 Household questionnaire empowerment module e.g. Programs make: no difference | a small difference | a big difference | a negative difference Being able to resolve disputes Membership of any local groups e.g. clubs or samitties Being able to choose who you vote for in elections Being able to complain to government officials Participating in development projects Being able to get clean water Access to news and information Being able to choose what work you do Keeping children in school 13 Bangladesh – PSM methodology Unobserved determination & social capital Observable proxies on information & attending beneficiary meetings + factors affecting “lobbying” Standard PSM approach SSNP Empowerment Biased results Our PSM approach SSNP Empowerment Unbiased results 14 Bangladesh – methodology, cont’d We distinguish asset-based agency (such as improved self-esteem) from actual empowerment outcomes (such as greater autonomy or more decision making in the household) WeAgency also distinguish between female-headed households in which the female heads are formally Iterative Degree of Development relationship widowed, separated,empowerment divorced or abandoned, and outcomes those where women run the household without Opportunity describing themselves in these terms structure Source: Alsop, Bertelsen and Holland (2006) 15 Bangladesh – findings 1. SSNP modestly contribute to women’s economic empowerment 2. FFW appears to have less economic impact than do other programs 3. SSNP have a bigger impact on keeping children in school than on access to credit, land, water or electricity 4. Old Age/other allowances pay for education of children within the extended family & PESP is used in other areas -- e.g. allowances are fungible 5. PESP is popular but could be better targeted 16 Bangladesh – findings, cont’d 1. FGDs in particular show that SSNP do enhance selfworth and self-esteem, and increase women’s access to information. 2. But -- increased self-esteem and access to information did not translate into empowerment as measured by observable changes in behaviour. Behavior change depends on changes in the norms governing acceptable female behaviour. Should husbands be part of VGD capacity building? 3. Expansion of the Food-for-Work and Money-for-Work schemes was the most frequently voiced request from FGDs, although these programs have the least economic impact. How to design better workfare programs? 17 Bangladesh – findings, cont’d SSNP had little effect on women’s social or civic empowerment (i.e. on autonomy, involvement in household decision-making and incidence of domestic violence). Old Age Allowances and VGD may actually result in negative impacts, perhaps because increasing women’s economic assets triggers a conservative backlash from poor and poorly educated husbands. Further in-depth qualitative analysis is needed on this issue. 18 Bangladesh – findings, cont’d 1. The combination of FGD and quantitative survey techniques worked well. Ideally, the questionnaire design would have built on earlier FGDs 2. The Empowerment Framework conception of empowerment as the outcome of asset-based agency interacting with institution-based opportunity structure is useful. 3. It is important to focus on de facto female headed households, not only those which identify themselves as “widowed, separated, divorced and abandoned”. 19 GHANA: Assessing empowerment effects of the Community Based Rural Development Project 20 Ghana - motivation The Community Based Rural Development Project (CBRDP) aims to empower rural populations by supporting the decentralization process, and more specifically, by improving delivery of rural water, health and education infrastructure We wanted to pilot measures to test: 1. CBRDP impact on people’s knowledge about local government and ways of demanding better service – social accountability agenda 2. Quantitative indicators of empowerment that could contribute a “demand-side” component to the new Functional Organizational Assessment Tool (FOAT) designed to measure local government capacity 21 Ghana - context CBRDP components include capacity building for local government officials to deliver better infrastructure, & training for beneficiary communities to effectively manage it In some CBRDP communities, work was carried out with communities on participatory planning under the Rapid Results Initiative (RRI). A Beneficiary Assessment planned for the mid-term review presented an opportunity to integrate measures of empowerment 22 Ghana – methodology overview CSC (6) PAM consult qualitative analysis CRC (927) Ordered logit & other quantitative analysis KI interviews from tracking study (110+153) CSC – Community Score Card CRC – Citizen’s Report Card KI – Key Informant 23 Ghana – Citizens’ Report Card CRC covered 927 households from 49 communities: 1. CBRDP communities without Rapid Results Initiative (RRI) 2. CBRDP communities from the same district with the RRI 3. A control group of non-CBRDP (but otherwise comparable) communities All respondents were asked questions on governance with sub-samples asked about education, health, water or roads. Five point Likert scale questions were used to capture perceptions of service quality (e.g. very dissatisfied through to very satisfied) 24 Examples of empowerment questions in CRC Did your wards experience any problem with this school in the last academic year? – 8 choices If so, what did you do about your major problem) 1. Nothing, I do not know who to approach 2. Nothing, no one could solve this problem 3. We tried to overcome this ourselves as best as we could 4. Went to see: List of possible representatives Were you satisfied with the solution? 1. Yes 2. No, nobody tried to help 3. No, they tried but I was not satisfied 25 Ghana – Community Score Card and Key informant interviews CSC undertaken in 6 representative districts: 1. Community members in an open meeting 2. District Assembly officials as service providers 3. Interface meetings with community, DA officials and elected members Information, voice & negotiation issues emerged in community and interface meetings Tracking study of officials trained by CBRDP. Empowerment issues emerged in key informant interviews undertaken as part of the tracking study 26 Ghana – education findings CBRDP school construction projects (e.g. latrines) significantly raised parent satisfaction with education Both qualitative & quantitative analysis tell a similar story: • Parent satisfaction with services was enhanced by more direct involvement in educational matters. • If the PTA functions, parents were much likelier to be satisfied with their children’s education Looking at empowerment issues produced practical feedback for CBRDP. Extra value can be added by informing and involving parents (RRI, parental involvement via PTA to improve discipline) 27 Ghana – empowerment findings There was only limited empowerment of consumers to resolve problems of service delivery. For both CBRDP and control groups: •Health facility users didn’t know where to go to address problems. In education, even parents who did know where to address their concerns failed to do so. •The qualitative data suggested that parents failed to pursue complaints because previous complaints were either ignored or not addressed to their satisfaction. 28 Ghana – decentralization findings Only one-fifth had a good understanding of District Assemblies (the highest level of local government) There was similar or even greater levels of ignorance about the right to attend local government meetings, see meeting minutes, and know the content of the budget. Men from wealthier households and with greater levels of schooling were generally more knowledgeable than poorer groups, women, and people living in the Eastern Region. Will the poor lose out from decentralization? Local people need more information to communicate effectively with their DAs to secure better services 29 Ghana – RRI findings The Rapid Results Initiative (RRI) procedures had interesting empowerment impacts: They promoted greater accountability, transparency, ownership and effective management of associated sub-projects and will be adopted more widely. Their success suggests that community-driven development can result in greater empowerment and accountability in connection with the project that is being implemented. At the same time, evidence suggests that this success can cause local people to engage less with their existing Unit Committees. 30 Ghana – policy monitoring findings The indicators tested by the pilot could be used to monitor national processes as well. Specifically, they can provide a demand-side to the FOAT – to monitor decentralization The score card process itself was empowering. There is a need to establish structured consultation between consumers and service providers as part of a regular process of interaction, not as an ad-hoc event. 31 JAMAICA: Community-Based Policy Monitoring 32 Community-Based Policy Monitoring in Jamaica Objective To evaluate social policy execution, with a focus on the relationship between youth and service providers, in particular the police 33 Jamaica: Methodology A mixed-method approach applied in three communities: Community Score Card: – An interactive monitoring tool that generates quantitative and qualitative data – 5 empowerment indicators (perception scores of availability and exercise of choice) added to existing score card instrument • Peer ethnography – In-depth analysis of underlying power relations by “peer researchers” looking at: Identity, support and authority; and police-youth relations. 34 Community Score (Scale: 1= Very poor; 2= Poor; 3= Fair; 4= Good; 5= Excellent). Indicator Harasson Gardens Poyuton Terrace Coolblue Gap Violent, poor urban Stable, poor urban Poor rural Original indicators Level of trust youth have in the police 1 4 4 Level of respect and courtesy displayed by the police 2 5 5 Level of fairness displayed by police 1 4 4 Level of responsiveness of police 3 3 2 Level of effort made by police to interact with the youth 2 5 3 Level of youth access to information about police activities and services 3 5 1 Level of youth willingness to use police services (e.g. reporting incidents) 4 5 4 Ability of youth to officially complain about inappropriate police behaviour / action 5 5 2 Level of youth willingness to officially complain about inappropriate police behaviour / action 1 4 4 Level of youth hope that police-youth relations can improve 2 5 5 Additional empowerment indicators 35 Jamaica: Findings and Recommendations •Social policy needs to address the agency of undervalued youth: Amongst poor urban and rural communities, youth have very little power in the presence of adults •Social policy needs to rebuild relevant institutions: Within inner city communities, in particular, young people have lost faith in traditional institutions, turning to self-reliance and alternative street/ gang institutions •Social policy needs to be geared towards employment generation to break the cycle of gun and alternative authority structures •While schooling is still perceived as fundamentally important institution in framing the life choices of young people, gender is becoming an increasingly significant factor in influencing choices and outcomes •Police-youth relations are at the centre of outsider-insider contact, and are problematic but not intractable 36 Measuring empowerment in Jamaica: Reflections •The application of a mixed method diagnostic tool allowed the evaluation to look at the problems affecting everyday service provider-user interaction, but also to delve deeper to examine the social structural issues of class, gender and social hierarchy. •Rather than simply tinkering with policy implementation at the interface of police-youth relations (a kind of “empowerment lite” approach), the tool can generate more “upstream” and crosssectoral social policy analysis. 37 Conclusions and recommendations 38 Cross-cutting findings • Measuring empowerment is important where objective is pro-poor policy or social inclusion • Empowerment measurement methodologies can themselves be empowering locally while energizing macro-level policy discussions • Empowerment indicators can be integrated into existing surveys but care is needed over choice of indicators when aggregating • Mixing methods results in better, more nuanced information that yields policy-relevant insights on power relations underpinning everyday interactions • Mixed methods result in different types of evidence that appeal to diverse stakeholders 39 Cross-cutting recommendations • Work with local stakeholders to identify empowerment indicators • Include empowerment indicators in ongoing M & E exercises • Actively support use of appropriately sequenced mixed methods • Link empowerment measurement with policy interventions that focus on assets and institutions • Track impact of reforms that change relations between citizens and officials (service provisions, decentralization, etc.) where disempowerment of poor can be unintended consequence 40