Reading Portraiture

advertisement

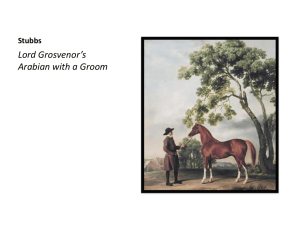

Understanding and Reading Portraiture Introduction • Portrait: A likeness or image of a person that is created by an artist. • Sitter (or patron in the context of a portrait): The person or people who are in a portrait. • Symbol: Something representing something else by association; objects, characters, or other visual representations of an abstract idea, concept, or event. The Patron and the Painter • The demand for portraits has been widespread since the eighteenth century, the time when Pompeo Batoni worked as a portrait artist in Italy. • Some people who became very wealthy commissioned portraits which included their grand newly built mansions, parks, estates and families to show off their wealth and importance. • Likeness was all-important to most patrons; after all, portraits were mainly a way of recording and remembering the patron for posterity. For this reason the wealthy nobility also commissioned paintings of their houses and even their favourite animals. • Because the portraits were intended to make the person seem very important it was also necessary for the portraits to be flattering and dignified. • In early portraits, many patrons wanted to include symbols of their profession or source of their riches within the painting. For example, a wealthy banker might like to be seen with a ledger or sitting at his desk inside the bank office. • As the art of portraiture developed though, the inclusion of other objects within the portrait became more subtle, often suggesting a location for the portrait which would frequently have been made to record a special trip or tour. the role of the artist and the patron • By 1780 portrait painting was big business across Europe. There were over 100 portrait painters in London alone. So, with all these painters competing for trade and commissions, the patrons became increasingly powerful and demanding and expected to be treated with enormous respect by the artists. • Most wealthy people went to the big cities to have their portrait painted and anyone who wanted to appear important needed a portrait of themselves as a status symbol, in the same way as people show off their wealth today through expensive possessions, cars, etc. • Some portrait painters did stay in the countryside, although they could not earn as much and commissions were fewer, so most tended to head for the city in the end. • Even the beginning of photography in the mid 19th Century didn’t reduce the popularity of portraiture. This was because portraits were seen as status symbols in gilt frames, which photos couldn’t imitate. However, the trade in miniature portraits was killed by photography. Van Dyck and C17th English Portraiture • Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641) was a very popular portrait painter in England until his death in 1641. Van Dyck and the other most popular portrait artists at the time, were on an equal standing with their patrons and could therefore make some of their own decisions about the way the portrait was painted and also charged very high prices for their work. These artists employed ‘drapery assistants’ to paint the costumes in the pictures, while the main artist only really did the faces. In many cases, the patron was asked to choose from a selection of designs for the background, pose, costume etc. which the assistant painters then reproduced once the face was painted. Hudson and C18th English Portraiture • Thomas Hudson (1701-1779) still worked in a similar way to the earlier painters, with patrons choosing from stock poses and often created portraits of women with exactly the same posture, clothes and jewellery in several different portraits, with the only real difference being their faces! • Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) was the last English portrait painter to work in this way. • Artists like Reynolds didn’t bother too much about getting to know their patron and just looked at their faces, working in a very business-like way. The artists knew exactly how long they needed the patron to sit for their portrait, which was often as little as 3 sittings of 2 hours each. This reflects the industrial workman-like approach to portraiture at the time. • In contrast, by the end of the C19th, artists such as Whistler would ask patrons to sit up to 60 times for a single portrait, demonstrating the level of involvement and artistry artists evident by this time. Artists by now wanted to really get to know their patrons to convey their personality through the painting. The early C19th • Around the end of the C18th, artists began to move away from using assistants and increasingly tended to complete the entire painting themselves. This was because portraits were beginning to be seen as works of art in themselves and became increasingly individual and less massproduced. Clothing in Portraits • In the C17th sitters were often painted in clothing which was not their own, as they wanted to be portrayed as a figure from myths and legends (this type of painting is called allegorical). Reynolds took this idea a bit further, by wrapping his sitters in silk gowns etc. to make them look more wealthy and attractive – the artists would have a stock of ‘dressing up’ clothes available in their studios. • From the C19th onwards though, sitters were generally portrayed in their own clothes. Sometimes the artist would borrow the clothes from the sitter to finish off working from after the sitter had left. Artists as Salesmen • Artists had to be good salesmen too, so they made sure that the rooms in their homes where they welcomed visitors displayed some of their most impressive paintings which they made deliberately to advertise their skills. They also made engravings (prints) of their best portraits which could be reproduced and displayed to again advertise their skills. How to understand portraits • • • • • • Start by looking carefully. Try to consider all these aspects: What kind of pose is the sitter in? What objects are there as well as the person in the portrait? Use as many adjectives as you can think of to describe sitter. What clothing is the sitter wearing and is it their own? What media was used to create the portrait – why was that? Is the portrait set indoors or outside? In the artist’s studio or the sitter’s home/ Are they on holiday? • Once you’ve spent time looking and thinking, try to work things out by analysing what you can see and know: • Who is the sitter – why might they have had this portrait made? • What do the objects tell us about the sitter? • Who is the artist – what do you know about him/her? • When was the portrait created – what art movements were happening at the time? • What was going on in history when the portrait was created? Look at some Modern and Contemporary examples of portraiture and compare them to Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo examples – what do you notice? Some interesting artists to research include : • Chris Ofili, • Peter Blake (“Self-portrait with Badges”), • Chuck Close, • Jenny Saville What does the pose and gesture convey and how does portraiture differ from self-portraiture?